Our Lady of Mount Carmel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacred Heart Catholic Church 2015 Adams Avenue Huntington, WV 25704

Sacred Heart Catholic Church 2015 Adams Avenue Huntington, WV 25704 He instructed them to take nothing for the journey but a walking stick— no food, no sack, no money in their belts. They were, however, to wear sandals but not a second tunic. He said to them, “Wherever you enter a house, stay there until you leave from there. Whatever place does not welcome you or listen to you, leave there and shake the dust off your feet in testimony against them.” Mk 6:8 Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Center Activities Parish Council Chairperson Ron Gazdik ........................ (304) 417-1213 Parish Office Hours Parish Pastoral Council St. Ann Circle President Mon - Fri...................... 9:00AM - 12:00PM 3rd Monday of month................... 6:00PM Lydia Spurlock ................... (740) 744-3428 Phone ………………………….… (304) 429-4318 St. Ann Circle Parish E-mail ……..... [email protected] 2nd Tuesday of month .................. 1:00PM Sacraments Parish Facebook …………..fb.com/shcchwv Parish Website……...http://shcchwv.com/ Your Parish Staff Reconciliation Saturday 4:00 PM - 4:45 PM Administrator Anytime by appointment. Baptism Worship Rev. Fr. Shaji Thomas ……. (248) 996-3960 By appointment. Parents should be registered in Weekend Liturgies [email protected] parish at least 6 months. Instructions required. Saturday Evening .......................... 5:00PM Parish Secretary Marriage Sunday Morning ........................... 9:00AM Theresa Phillips ................ (703) 969-0542 Arrangements made AT LEAST 6 months in advance. (Bulletin Deadline: Monday by 10:00AM) Instructions required, and parishioners registered in Weekday Liturgies Bookkeeper the parish at least 1 year. Anointing of the Sick Monday ......................................... 8:30AM Lena Adkins ....................... (304) 486-5370 Please notify Fr. -

Our Lady of Mount Carmel

the catholic community of [Type text] [Type text] [Type text] the catholic community of OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL Volume 2, Issue 29: July 19, 2015 Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Our Lady of Mount Carmel 10 County Road Tenafly, NJ 07670 201.568.0545 www.olmc.us Volume 2, Issue 29 Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Staff Directory Pastor Reverend Daniel O’Neill, O.Carm. t - 201.568.0545 e - [email protected] Church Office Elizabeth Gardner, Office Manager Mary Ann Nelson, Receptionist t - 201.568.0545 f - 201.568.3215 e - [email protected] Roxanne Kougasian, Secretary Masses t - 201.871.4662 e - [email protected] Daily Deacons Monday – Saturday 8:30 AM Deacon Lex Ferrauiola Weekends e - [email protected] Saturday 5:00 PM Deacon David Loman Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 12:00 NOON e - [email protected] Mission Development Holy Days As announced Elliot Guerra Director of Mission Development Sacraments t - 201.568.1403 e - [email protected] The Sacrament of Reconciliation Liturgy & Pastoral Ministry Saturday 4:00 – 4:30 PM, Alicia Smith or by appointment, please call the Church Office Director of Liturgy & Pastoral Ministry The Sacrament of Baptism t - 201.871.9458 e - [email protected] The second Sunday of each month, except during Lent. Please arrange for Music Ministry Baptism at least two months in advance. Peter Coll, Music Director The Sacrament of Marriage t - 201.871.4662 Please make an appointment with a priest or deacon at least one year in e - [email protected] advance. Religious Education Office Sr. -

Una Aproximación Teológico-Litúrgica a Los Formularios Pascuales

UNIVERSIDAD DE NAVARRA FACULTAD DE TEOLOGÍA Félix María AROCENA SOLANO LAS PRECES DE LA LITURGIA HORARUM. Una aproximación teológico-litúrgica a los formularios pascuales Extracto de la Tesis Doctoral presentada en la Facultad de Teología de la Universidad de Navarra PAMPLONA 2002 Ad normam Statutorum Facultatis Theologiae Universitatis Navarrensis, perlegimus et adprobavimus Pampilonae, die 1 mensis iulii anni 2002 Dr. Ioseph Antonius ABAD Dr. Ioseph Ludovicus GUTIÉRREZ Coram tribunali, die 28 mensis iunii anni 2002, hanc dissertationem ad Lauream Candidatus palam defendit Secretarius Facultatis Eduardus FLANDES Excerpta e Dissertationibus in Sacra Theologia Vol. XLIII, n. 7 PRESENTACIÓN La reforma litúrgica del Concilio Vaticano II, que —en la opinión mayoritaria de los autores— alcanzó una de sus realizaciones más lo- gradas precisamente en la reinstauración del Oficio romano, se mues- tra como un vasto campo de investigación donde no todo está dicho. Muestra clara de ello lo constituyen las Preces que representan, si no una novedad, sí, al menos, un elemento sustancialmente reinstaurado al que hasta hoy se le ha prestado escasa atención. De hecho, siendo una producción eucológica tan vasta —abarca más de 200 formula- rios que abrazan 1.300 fórmulas—, tras una indagación bibliográfica lo más exhaustiva posible en varias lenguas, hemos encontrado cinco artículos —todos ellos extranjeros— relativamente generales, breves, descriptivos y ninguna obra completa dedicada a su estudio porme- norizado y abarcante de todas sus dimensiones, tales como la historia, la teología, la espiritualidad, la pastoral e incluso un análisis filológico de los textos. Por lo que se refiere a la teología sistemática, echamos en falta un estudio de tipo contenutístico de las Preces, laguna que noso- tros intentamos ahora rellenar mediante el análisis de la pneumatolo- gía y eclesiología contenida en los formularios del tiempo de Pascua. -

Blessing and Investiture Brown Scapular.Pdf

Procedure for Blessing and Investiture Latin Priest - Ostende nobis Domine misericordiam tuam. Respondent - Et salutare tuum da nobis. P - Domine exaudi orationem meum. R - Et clamor meus ad te veniat. P - Dominus vobiscum. R - Et cum spiritu tuo. P - Oremus. Domine Jesu Christe, humani generis Salvator, hunc habitum, quem propter tuum tuaeque Genitricis Virginis Mariae de Monte Carmelo, Amorem servus tuus devote est delaturus, dextera tua sancti+fica, tu eadem Genitrice tua intercedente, ab hoste maligno defensus in tua gratia usque ad mortem perseveret: Qui vivis et regnas in saecula saeculorum. Amen. THE PRIEST SPRINKLES WITH HOLY WATER THE SCAPULAR AND THE PERSON(S) BEING ENROLLED. HE THEN INVESTS HIM (THEM), SAYING: P - Accipite hunc, habitum benedictum precantes sanctissima Virginem, ut ejus meritis illum perferatis sine macula, et vos ab omni adversitate defendat, atque advitam perducat aeternam. Amen. AFTER INVESTITURE THE PRIEST CONTINUES WITH THE PRAYERS: P - Ego, ex potestate mihi concessa, recipio vos ad participationem, omnium bonorum spiritualium, qua, cooperante misericordia Jesu Christi, a Religiosa de Monte Carmelo peraguntur. In Nomine Patris + et Filii + et Spiritus Sancti. + Amen. Benedicat + vos Conditor caeli at terrae, Deus omnipotens, qui vos cooptare dignatus est in Confraternitatem Beatae Mariae Virginis de Monte Carmelo: quam exoramus, ut in hore obitus vestri conterat caput serpentis antiqui, atque palmam et coronam sempiternae hereditatis tandem consequamini. Per Christum Dominum nostrum. R - Amen. THE PRIEST THEN SPRINKLES AGAIN WITH HOLY WATER THE PERSON(S) ENROLLED. English Priest - Show us, O Lord, Thy mercy. Respondent - And grant us Thy salvation. P - Lord, hear my prayer. R - And let my cry come unto Thee. -

PRESS RELEASE St. Josemaría and Theological Thought

© 2013 - PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY OF THE HOLY CROSS Communication Office [email protected] PRESS RELEASE International Conference St. Josemaría and theological thought 14-16 November 2013 * * * ROME, 11 NOV 2013 – What do the saints represent for theology? It will be this ba- sic question that will accompany the undertakings of the International Conference St. Josemaria and theological thought, to be held from Thursday 14 to Saturday 16 November at the Pontifical University of Santa Croce (Piazza St. Apollinaris, 49) Organized by the Chair of St. Josemaria active in the Faculty of Theology, gathers for three days experts, professors and students interested – as the Rev. Prof. Javier López of the organizing committee explains – “the renewal of Theology through the means of the life and writings of the saints.” To this regard, “we will focus in particu- lar on the teachings of St. Josemaria, not because it is treated as an isolated case, but because there are very well suited to highlight the value of saints for Theology.” The origin of the setting of this conference goes back to the message of the then Car- dinal Joseph Ratzinger addressing participants at a preceding Theological Sympo- sium on the teachings of St. Josemaria held at Santa Croce in 1993, in which he noted that “Theology, science in the full sense of the word (…) is subordinate to the knowledge that God has of Himself and of which the blessed enjoy.” The future Benedict XVI was not only referring to the knowledge which the saints enjoy in glory, but also to those that themselves have begun to have it on this earth and which are arrived at with their writings, their words and their example. -

Immaculate Mary Music Pdf

Immaculate mary music pdf Continue This article is about the popular Marian anthem. For Catholic teachings and Mary's devotion under this name, see The Immaculate Conception. Part of the series at TheMariologyof Catholic ChurchVirgo Joseph Moroder-Luzenberg Review of Prayers Antiphones Hymns Mary Dedication practices the Holy Society of consecration and laying the Veneration of Angelus Prayer As a Child, whom I loved you Fatima Prayer Flos Carmeli Grad Mary Maria Golden Immaculata Prayer Magnificent Mary, Mother Grace Mary Our queen Memorare Tuum praesidium Antiphons Alma Redemptoris Mater Ave maris stella Ave Regina caelorum Salve Regina Hymns Mary Grad queen of heaven , Ocean star of the Immaculate Maria Ave de Fatima Lo, As Rose E'er Blossoms O sanctissima Regina Caeli Stabat Mater Initiation Practices Laws on the Dedication of Mary First Saturday Rosary Seven Joys of the Virgin Seven Sorrows of Mary Three Grad Marys movements and societies Sodality Our Lady of the Congregation Marian Mary 'Monfort' Marianists (Mary Society) Marist Fathers Marist Brothers Schoenstatt Movement Legion Of Mary World Apostle Fatima (Blue Army) Mariological Society Our Lady Rosary Makers Marian Movement priests Fatima Family Apostolicity Of the Appreitative Pope Aparecida Banne Bornee Fatima Guadalupe La Salette Lourdes Miracle Medal Pontmain Key Marian Feast of the Days of the Mother of God (January 1) Annuncia (March 25) Assumption (August 15) Immaculate Conception (December 8) Catholicism portalvte Immaculate Mary or Immaculate Mother (French: Vierge Marie) is a popular Roman Catholic It is also known as the Lourdes Anthem, a term that also refers only to melody. It is often singed in honor of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. -

THE WISDOM of the CROSS in a PLURAL WORLD Pontifical Lateran University, 21-24 September 2021

FOURTH INTERNATIONAL THEOLOGICAL CONGRESS FOR THE JUBILEE OF THE THIRD CENTENARY OF THE FOUNDATION OF THE PASSIONIST CONGREGATION THE WISDOM OF THE CROSS IN A PLURAL WORLD Pontifical Lateran University, 21-24 September 2021 Tuesday 21 September 2021 - THE WISDOM OF THE CROSS AND THE CHALLENGES OF CULTURES 8.30 Registration and distribution of the Congress folder 9.00 The session is chaired by H. Em. Card. Joao Braz De Aviz, Prefect of the Congregation for Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life Moderator: Ciro Benedettini CP, President of the Centenary Jubilee Enthronement of the Crucifix and prayer. Greetings from the Rector Magnificus of the Pontifical Lateran University, Prof. Vincenzo Buonomo Presentation: Fernando Taccone CP, director of the Congress, Pontifical Lateran University Opening Address: The wisdom of the cross as a way of reconciliation in a plural world, Most Reverend Rego Joachim, Superior General of the Passionists Interval 10.45 Lecture: The Wisdom of the Cross and the Challenges of Cultures: Biblical aspect: Prof. Antonio Pitta, Pro-Rector of the Pontifical Lateran University 11.30 Theological aspect: Prof. Tracey Rowland, University of Notre Dame of Australia 12.30 Lunch break 14.30 Secretariat open 14.30 Opening of the exhibition on the Passion of Christ and photographic exhibition of the socio-apostolic activity of Dr. Frechette Richard CP in Haiti, supported by the Francesca Rava Foundation (MI) 15.00 Linguistic session: The Wisdom of the Cross as a factor of provocation and challenge in today's cultural areopagus Italian section. Moderator: Prof. Giuseppe Marco Salvati OP, Pontifical Angelicum University Lecture: The wisdom of the Cross: crossroads of pastoral discernment, Prof. -

Table of Contents Bulletin

Bulletin 2014-2015 Table of Contents The Seal . 3 Mission . 4 History . 7 Campus . 9 Trustees, Administration, Staff . 12 Faculty . 14 Academic Policies and Procedures . 23 Constantin College of Liberal Arts . 34 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Undergraduate) . 39 Campus Life . 40 Undergraduate Enrollment . 49 Undergraduate Fees and Expenses . .56 Undergraduate Scholarships and Financial Aid . 62 Requirements for the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science Degrees . 68. Course Descriptions by Department . 72 Rome and Summer Programs . 249 Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts . 260 The Institute of Philosophic Studies Doctoral Program . 271 Braniff Graduate Master’s Programs . 287 School of Ministry . 316 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) . 332 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) Calendar . .371 Undergraduate, Braniff Graduate School and School of Ministry Calendar . 373 Index . 379 Map . 384 University of Dallas, 1845 East Northgate Drive, Irving, Texas 75062-4736 General Office Hours: 8:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m., Monday through Friday www .udallas .edu Main Phone . (972) 721-5000, Fax: (972) 721-5017 Braniff Graduate School of Liberal Arts . (972) 721-5106 Business Office . (972) 721-5144 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business . (972) 721-5200 Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business (Graduate) . (972) 721-5004 Registrar . (972) 721-5221 Rome Program . (972) 721-5206 School of Ministry . (972) 721-4118 Special Assistance . (972) 721-5385 Undergraduate Admission . (972) 721-5266 THE SEAL 3 The Seal The seal of the University of Dallas is emblematic of the ideals to which the University is dedicated . It is likewise reminiscent of the deposit of faith of the Roman Catholic Church and of the traditions of two teaching communities within the Church . -

Winter 2020 Flos Carmeli Volume XXIX No

Winter 2020 Flos Carmeli Volume XXIX No. 2 Oklahoma Province Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites From the President’s Desk By Claire Bloodgood, OCDS—President of the Provincial Council Hello Carmelites, Praised be Jesus Christ – now and forever. Hello Carmelites, Well, this is my last report to the OCDS of St Therese Province. By the time you see this I will be back in my own community and another PC President will be in harness. Being on the Provincial Council has been an adventure, always something new. I’ve enjoyed meeting so many Seculars around the Province, each person unique and yet each person a Carmelite. I hold you in my heart. New to the Provincial Council Inside this issue: Mark Calvert, Maxine Latiolais, and Barbara Basgall are now on the PC and PC Channel— 3 eager to serve you and the Lord. Please see their introductions found on Pastoral Care of the Secular Order Pages 4-6. Jill Parks and Anna Peterson are continuing on until 2023. We are blessed to have these five devoted Carmelites. God is good. New PC Member— 4 Barbara A. Basgall, OCDS Local Council Elections New PC Member— 5 Mark Calvert, OCDS Please remember that OCDS community elections must be held before the Friars’ chapter meeting. This year that means no later than early May. New PC Member— 6 Maxine Latiolais, OCDS Some of you will have already had your elections. A thorough handoff will Christmas Greeting - 7-9 help your incoming Councils get up and running smoothly. Father Bonaventure Sauer, There are some excellent articles on the website that address local Council OCD concerns and how a healthy Council functions. -

NICCSJ Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel 2021

NICCSJ 2021 Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel (Feast Day, July 16th) Mount Carmel is the biblical site where the prophet Elijah battled with the 450 priests of Baal, which led to their defeat and ruin. It was also where Elijah sent his servant seven times to the mountaintop to look for rain after years of drought which ended as he proclaimed (1 Kings 18:19-44). The title of Our Lady of Carmel can be traced back to the hermits (Carmelites) who used to live in the renowned and blessed Mount Carmel. These pious and austere Carmelites prayed in expectation of the advent of a Virgin-Mother. Thousands of years later, our Lady, Mary appeared to St. Simon Stock, a Carmelite priest, in the exact same location on July 16th 1251. In this appearance of Mary, she is known as Our Lady of Mount Carmel. She appeared holding Jesus as a child in one arm and on her other arm, a Scapular. She promised that all those who wear Scapular and follow Christ faithfully will be brought by Our Mother Mary into heaven at their deaths. Praying the Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel has been an age-long practice through which Christians have entrusted their intentions to God through the powerful intercessions of our Mother Mary. Let us continue to share in the maternal love our Mother Mary by praying this Novena with devotion and attention. Amen Thursday July 8th to Friday July 16th, 2021 Modality: Daily at 8.00PM: • Sundays & Saturdays through Community Zoom- https://us02web.zoom.us/my/niccsj, 1D- 9206647431, Passcode- 424258 • Monday to Friday through Community Prayer Line: Dial in #- +18482203100; ID #-06122005# Steps: 1. -

Some Striking

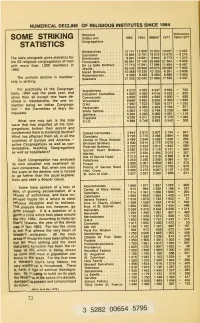

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Novena (With Litany) to Our Lady of Mount Carmel

Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel Feast: July 16 Novena Format • Sign of the Cross • Daily Prayer (see below) • (pause and mention petitions) • Recite together Our Father, Hail Mary and Glory Be • Talk for the Day and Discussion • Litany of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel (see reverse) • “Daily Closing Prayer” (see below) • Flos Carmeli Daily Novena Prayer First Day — July 7 Sixth Day — July 12 O Beautiful Flower of Carmel, most fruitful vine, With loving provident care, O Mother Most Amiable, splendor of heaven, holy and singular, who brought forth you covered us with your Scapular as a shield of defense the Son of God, still ever remaining a pure virgin, assist against the Evil One. Through your assistance, may we us in our necessity! O Star of the Sea, help and protect bravely struggle against the powers of evil, always open us! Show us that you are our Mother! to your Son Jesus Christ. Second Day — July 8 Most Holy Mary, Our Mother, in your great love for us Seventh Day — July 13 you gave us the Holy Scapular of Mount Carmel, having O Mary, Help of Christians, you assured us that wearing heard the prayers of your chosen son Saint Simon Stock. your Scapular worthily would keep us safe from harm. Help us now to wear it faithfully and with devotion. Protect us in both body and soul with your continual aid. May it be a sign to us of our desire to grow in holiness. May all that we do be pleasing to your Son and to you.