2018 Poster Abstract Book Posters Are Listed Alphabetically by the Presenter’S Last Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montanans on Dig in Middle East Solve Puzzle

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 11-3-1983 Montanans on dig in Middle East solve puzzle University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Montanans on dig in Middle East solve puzzle" (1983). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 8365. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/8365 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I IX, 93 of Montana Office of University Relations • Missoula, Montana 59812 • (406) 243-2522 MEDIA RELEASE dwyer/vsl 11-3-83 dai1ies + Northridge, Coeur d'Alene, Nashville, Portland, w/pic MONTANANS ON DIG IN MIDDLE EAST SOLVE PUZZLE By Maribeth Dwyer University Relations University of Montana MISSOULA— A puzzle long pondered by students of antiquities has been solved by a University of Montana team working on an archaeological dig at Qarqur in northwestern Syria. The city is on the Orontes River, about 30 miles frpm the Mediterranean and 12 miles from the Turkish border. Along with teams from Kansas State University, Brigham Young University and the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome, the UM group worked on excavation of the most prominent tell in the Orontes Valley. -

2008: 137-8, Pl. 32), Who Assigned Gateway XII to the First Building

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 29 November 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Osborne, J. and Harrison, T. and Batiuk, S. and Welton, L. and Dessel, J.P. and Denel, E. and Demirci, O.¤ (2019) 'Urban built environments of the early 1st millennium BCE : results of the Tayinat Archaeological Project, 2004-2012.', Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research., 382 . pp. 261-312. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1086/705728 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2019 by the American Schools of Oriental Research. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Manuscript Click here to access/download;Manuscript;BASOR_Master_revised.docx URBAN BUILT ENVIRONMENTS OF THE EARLY FIRST MILLENNIUM BCE: RESULTS OF THE TAYINAT ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, 2004-2012 ABSTRACT The archaeological site of Tell Tayinat in the province of Hatay in southern Turkey was the principal regional center in the Amuq Plain and North Orontes Valley during the Early Bronze and Iron Ages. -

13 Chapter 1548 15/8/07 10:56 Page 243

13 Chapter 1548 15/8/07 10:56 Page 243 13 Neo-Assyrian and Israelite History in the Ninth Century: The Role of Shalmaneser III K. LAWSON YOUNGER, Jr. IN HISTORICAL STUDIES, ONE OF THE COMMON MODES of periodization is the use of centuries. Like any type of periodization, this is intended to be flexi- ble, since obviously every turn of century does not bring about a sudden and radical change in material culture and/or trends in human thought and per- spective. The greatest problem with any periodization—whether based on archaeological periods, kingdoms, dynasties, ages, eras, Neo-Marxist cate- gories (like pre-modern, modern, post-modern)—is generalization. This is often manifested in an unavoidable tendency to emphasize continuity and understate changes within periods, while at the same time emphasizing changes and understating continuity between adjacent periods. In fact, peri- ods are artificial concepts that can lead at times to seeing connections that do not actually exist. They do not usually have neat beginnings and endings. Nevertheless, periodization is necessary to historical analysis and the use of centuries can prove functional in the process of imposing form on the past. In using centuries as a periodization scheme, some modern historians have resorted to the concepts of ‘long’ and ‘short’ centuries to better reflect the periods and their substantive changes. However, in the case of the history of Assyria,1 the ninth century does not accurately reflect periodization, even if long or short century designations are used. Typically, the ninth century has been understood as part of three discernible, yet interconnected, periods, two of which overlap into other centuries (the first with the previous tenth century and the third with the following eighth century) (see e.g. -

Urbanism in the Northern Levant During the 4Th Millennium BCE Rasha El-Endari University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2012 Urbanism in the Northern Levant during the 4th Millennium BCE Rasha el-Endari University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation el-Endari, Rasha, "Urbanism in the Northern Levant during the 4th Millennium BCE" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 661. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/661 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. URBANISM IN THE NORTHEN LEVANT DURING THE 4TH MILLENNIUM BCE URBANISM IN THE NORTHEN LEVANT DURING THE 4TH MILLENNIUM BCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Rasha el-Endari Damascus University Bachelor of Science in Archaeological Studies, 2005 December 2012 University of Arkansas Abstract The development of urbanism in the Near East during the 4thmillennium BCE has been an important debate for decades and with recent scientific findings, a revival of this intellectual discussion has come about. Many archaeologists suggested that urban societies first emerged in southern Mesopotamia, and then expanded to the north and northwest. With recent excavations in northern Mesopotamia, significant evidence has come to light with the finding of monumental architecture and city walls dated to the beginning of the 4th millennium BCE, well before southern Mesopotamian urban expansion. -

Des Bateaux Sur L'oronte

Des bateaux sur l’Oronte Julien Aliquot To cite this version: Julien Aliquot. Des bateaux sur l’Oronte. Dominique Parayre. Le fleuve rebelle. Géographie his- torique du moyen Oronte d’Ebla à l’époque médiévale, 4, Presses de l’Ifpo, pp.215-228, 2016, Syria, Supplément, 978-2-35159-725-5. halshs-01707683 HAL Id: halshs-01707683 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01707683 Submitted on 29 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SUPPLÉMENT IV SOMMAIRE VOLUME DE TEXTES SUPPLÉMENT IV Liste des contributeurs....................................................................................................................................................................3 Le fleuve rebelle Parayre.(D.),.Introduction............................................................................................................................................................5 d’Ebla à l’époque médiévale Al.Dbiyat..(M.),.L’Oronte, un fleuve de peuplement séculaire dans un milieu contrasté.....................................................................9 -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA021 Weekly Report 157–160 — September 1–30, 2017 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Allison Cuneo, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Kyra Kaercher, Darren Ashby, Jamie O’Connell, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 4 Incident Reports: Syria 12 Incident Reports: Iraq 122 Incident Reports: Libya 128 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 143 SNHR Vital Facilities Report: 148 Heritage Timeline 148 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points Syria ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ A reported US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed the Umm al-Mouminein Aisha Mosque in Ruwaished Village, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0161 ○ Satellite imagery shows damage to an Unnamed Mosque in al-Baghiliyah, Deir ez- Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0168 ● Hama Governorate ○ The Turkistan Islamic Party reportedly militarized Tell Qarqur in Qarqur, Hama Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0160 ● Hasakah Governorate ○ New video shows the condition of Mar Odisho Church in Tell Tal, Hasakah Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 16-0032 UPDATE ● Idlib Governorate ○ Looting and theft has compromised the archaeological site of Tell Danit in Qamnas, Idlib Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0163 ○ A suspected Russian airstrike damaged the Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Mosque in Jerjnaz, Idlib Governorate. -

Nternational Hydrographic Organization

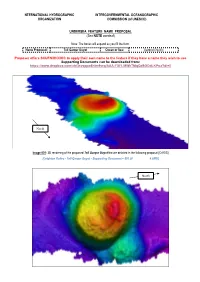

NTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC ORGANIZATION COMMISSION (of UNESCO) UNDERSEA FEATURE NAME PROPOSAL (Sea NOTE overleaf) Note: The boxes will expand as you fill the form. Name Proposed: Tell Qarqur Guyot Ocean or Sea: Central Pacific Proposer offers SCUFN/IHO/IOC to apply their own name to the feature if they have a name they wish to use Supporting Documents can be downloaded from: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/3svqqao6hlm9vrq/AAA-FXFLMWk7MqQd9GDdLKPua?dl=0 North Image 001: 3D rendering of the proposed Tell Qarqur Guyot feature detailed in the following proposal [CARIS] [Leighton Rolley - Tell Qarqur Guyot - Supporting Document – 001.tif 4.6MB] North Image 002: Overview of the proposed Tell Qarqur Guyot feature detailed in the following proposal [Fladermaus Product] [Leighton Rolley - Tell Qarqur Guyot - Supporting Document – 002.tif - 1.4MB] North Image 003:: Overview of the proposed Tell Qarqur Guyot feature detailed in the following proposal [Fladermau Product] [Leighton Rolley - Tell Qarqur Guyot - Supporting Document – 002.tif - 7.1 MB] Geometry that best defines the feature (Yes/No) : Point Line Polygon Multiple points Multiple lines* Multiple Combination of polygons* geometries* Yes North Image 004: Boundary perimeter of the proposed Tell Qarqur Guyot with 13 points defining the feature. Latitude and Longitude of individual points is given in the following table (Table 1.0) [Leighton Rolley - Tell Qarqur Guyot - Supporting Document – 004.tif - 4.17 MB] Table 1.0 - Points defining the outline of the proposed -

The Palaeoethnobotany of Tell Tayinat, Turkey

Urban Subsistence in the Bronze and Iron Ages: The Palaeoethnobotany of Tell Tayinat, Turkey by Mairi Margaret Capper B.Sc., University of Toronto, 2007 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology Faculty of Environment Mairi Margaret Capper 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada , this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Mairi M. Capper Degree: Master of Arts (Archaeology ) Title of Thesis: Urban Subsistence in the Bronze and Iron Ages: The Paleoethnobotany of Tell Tayinat, Turkey Examining Committee: Chair: Dongya Yang, Associate Professor, Archaeology A. Catherine D’Andrea Senior Supervisor Professor, Archaeology David Burley Supervisor Professor, Archaeology Timothy Harrison Supervisor Professor, Anthropology, University of Toronto Jennifer Ramsay External Examiner Assistant Professor, Anthropology, College at Brockport Date Defended/Approved: 20 August 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis examines macrobotanical remains recovered from Early Bronze Age and Iron Age (approximately 3300-600 BCE) deposits at Tell Tayinat in southern Turkey. Tell Tayinat was a large, urban centre which was situated in a region with favourable environmental conditions and higher rainfall compared to many other well-studied areas of the Near East. The most significant crop species present at Tell Tayinat are wheat (emmer and free- threshing), barley, bitter vetch, grape and olive. -

Settlement and Landscape Transformations in the Amuq Valley, Hatay. a Long-Term Perspective Introduction

Settlement and Landscape Transformations in the Amuq Valley, Hatay. A Long-Term Perspective Fokke Gerritsen, Andrea De Giorgi, Asa Eger, Rana Özbal, Tasha Vorderstrasse1 Introduction Fokke Gerritsen A decace of regional survey between 1995 and 2005 in the Amuq Valley in the Hatay province of southern Turkey (fig. 1), following seminal work done in the 1930s (Braidwood 1937), has produced extensive datasets to study the history of human occupation and landscape development in the region. The main insights from the work done by the Amuq Valley Regional Project (AVRP) have been presented recently by Casana and Wilkinson (2005a, in Yener 2005), with significant earlier publications including the University of Chicago dissertation by Jesse Casana (2003), and a multi-authored report on the 1995 to 1998 fieldwork seasons (Yener et al. 2000a). Particularly important results of the project concern the complex interplay between human settlement and environmental history in the later first millennium BCE and the first millennium CE. These accomplishments of research and publication notwithstanding, ongoing research, including long-term excavation projects in the Amuq Valley at Tell Atchana and Tell Tayinat, continues to refine and alter our current understanding on many points, in particular concerning the Bronze and Iron Ages. There are good reasons, however, to present a synthesis at this point in time on the landscape and settlement history of the Amuq Valley, focusing on transformations in two separate periods, i.e. the pottery-Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods on the one hand, and the Hellenistic to Ottoman periods on the other. Our understanding of the nature and background of transformations in the settlement patterns in these periods has improved significantly in recent years. -

Trade Or Migration? a Study of Red-Black Burnished Ware at Tell Qarqur, Syria

TRADE OR MIGRATION? A STUDY OF RED-BLACK BURNISHED WARE AT TELL QARQUR, SYRIA by Kyra Elise Kaercher Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Kyra Elise Kaercher All Rights Reserved ii TRADE OR MIGRATION? A STUDY OF RED-BLACK BURNISHED WARE AT TELL QARQUR, SYRIA Kyra Kaercher, B.A. University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, 2010 Abstract Both trade and migration have been used by archaeologists to explain change in material culture. In particular, archaeologists have interpreted changes in the types of ceramics recovered at archaeological sites as evidence of either regional trade and/or the migration of people into the area. The appearance of one particular ceramic type, Red-Black Burnished Ware (RBBW) in the Ancient Near East circa 2500 B.C. has been explained as resulting from either trade or the migration of people. RBBW is distinct from the local wares, but appears similar to ceramics found in Transcaucasia (present day Republic of Georgia) (Rothman 2002). One site at which RBBW is found is the site of Tell Qarqur, Syria. This paper will examine the forms of pottery vessels recovered at Tell Qarqur to determine their function in order to demonstrate whether the occurrence of this pottery at the site can be attributed to trade or migration. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Undergraduate Research and Creativity Grant Committee for supporting my trip to Syria so I could gather my data. -

Revisiting the Amuq Sequence: a Preliminary Investigation of the EBIVB Ceramic Assemblage from Tell Tayinat

Revisiting the Amuq sequence: a preliminary investigation of the EBIVB ceramic assemblage from Tell Tayinat Lynn Welton The chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the Northern Levant has been constructed around a small group of key sequences and excavations, including the Amuq Sequence. Information about this sequence has predominantly been taken from excavations conducted in the 1930s. The final Early Bronze Age phase in the Amuq (Phase J, EBIVB) was, however, based on a comparatively small sample of ceramics originating only from the site of Tell Tayinat. Excavations of EBIVB levels by the Tayinat Archaeological Project have provided a larger sample of Amuq Phase J ceramics, which are described here, quantified and evaluated in comparison to the original Braidwood collection and to the larger Northern Levantine region. Keywords Early Bronze Age, Amuq, Northern Levant, ceramics, quantitative analysis Introduction This article examines the ceramic assemblage dating Examinations of the chronology of the Early Bronze to the EBIVB period (Amuq Phase J) that has been Age in the Northern Levant have traditionally collected by the excavations of the Tayinat focused around a few key sequences and excavations. Archaeological Project (TAP) (Welton et al. 2011). Among these is the Amuq Sequence, which was described in a seminal publication by Robert and Tayinat Archaeological Project investigations Linda Braidwood in 1960. One of the remarkable Tell Tayinat and its history of excavations aspects of this work is its longevity and resilience; it The Amuq Plain is situated in a strategic location, remains one of the most commonly cited sources for linking routes between the Anatolian highlands, the the archaeology of this period. -

Shalmaneser III and the Levantine States: the “Damascus Coalition” Shalmaneser III and the Levantine States

The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures ISSN 1203-1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI and THEOLDI. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by the National Library of Canada, and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by the The National Library of Canada. Volume 5: Article 4 (2004) A. Kirk Grayson, “Shalmaneser III and the Levantine States: The “Damascus Coalition” Shalmaneser III and the Levantine States: 1 The “Damascus Coalition Rebellion” A. Kirk Grayson University of Toronto 1. Introduction To begin this paper, I shall quote, from the statement sent to me by Professor Andy Vaughn when he invited me to participate in a symposium “Biblical Lands and Peoples in Archaeology and Text”. The goal of this session “is to promote the interaction between biblical scholars and archaeologists as well as other specialists in ancient Near Eastern Studies … the gap between biblical scholars and specialists in Assyriology and other fields like archaeology continues to grow wider”. The widening gap is certainly a real phenomenon, the main reason being the astounding increase in data through publications, archaeology, research in museums and related institutions, and the tremendous increase in numbers of scholars in the relevant fields. As a personal note on this theme, I — like many of my contemporaries — came to Assyriology from a base in the Hebrew bible. In those days, the 1960s, 1950s, and before, it was generally assumed that an Assyriologist, an Egyptologist, etc.