Bioacoustic and Multi-Locus DNA Data of Ninox Owls Support High Incidence of Extinction and Recolonisation on Small, Low-Lying Islands Across Wallacea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prey Ecology of the Burrowing Owl Athene Cunicularia Cunicularia (Molina, 1782) on the Northern Coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nnfe20 Prey ecology of the burrowing owl Athene cunicularia cunicularia (Molina, 1782) on the northern coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil Alana Drielle Rocha , J. O. Branco & G. H. C. Barrilli To cite this article: Alana Drielle Rocha , J. O. Branco & G. H. C. Barrilli (2021): Prey ecology of the burrowing owl Athenecuniculariacunicularia (Molina, 1782) on the northern coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil, Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2020.1867953 Published online: 13 Jan 2021. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=nnfe20 STUDIES ON NEOTROPICAL FAUNA AND ENVIRONMENT https://doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2020.1867953 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Prey ecology of the burrowing owl Athene cunicularia cunicularia (Molina, 1782) on the northern coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil Alana Drielle Rocha a, J. O. Branco b and G. H. C. Barrilli a aDepartment of Biological and Health Sciences, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil; bSchool of the Sea, Science and Technology, Vale do Itajaí University, Itajaí, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY We analyzed the diet of Athene cunicularia cunicularia in order to identify and compare prey items Received 14 August 2020 in dune populations in Santa Catarina, Brazil: Interpraias (INT), Praia Brava (BRA), Praia Central Accepted 20 December 2020 (NAV) and Peninsula (BVE). Due to the characteristics of urbanization in these regions, we hypothesized that there would be greater abundance and consumption of urban insect pests KEYWORDS Burrowing owl; dunes; diet; in the areas of BRA, NAV, and INT than in BVE. -

CITES Norfolk Island Boobook Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II (Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)) PERIODIC REVIEW OF NINOX NOVAESEELANDIAE UNDULATA 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.1 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends the transfer of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata from CITES Appendix I to CITES Appendix II, in accordance with provisions of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev CoP16), Annex 4 precautionary measure A.1. and A.2.a) i). 1 The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 Annex CoP17 Prop. xx CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

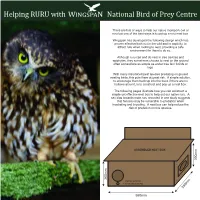

(Ruru) Nest Box

Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre There are lots of ways to help our native morepork owl or ruru but one of the best ways is to put up a ruru nest box. Wingspan has developed the following design which has proven effective both out in the wild and in captivity, to attract ruru when looking to nest, providing a safe environment for them to do so. Although ruru can and do nest in tree cavities and epiphytes, they sometimes choose to nest on the ground often somewhere as simple as under tree fern fronds or logs. With many introduced pest species predating on ground nesting birds, this puts them at great risk. A simple solution, to encourage them back up into the trees if there are no hollows around, is to construct and pop up a nest box. The following pages illustrate how you can construct a simple yet effective nest box to help out our native ruru. A sex bias towards male ruru recorded in one study suggests that females may be vulnerable to predation when incubating and brooding. A nest box can help reduce the risk of predation on this species. ASSEMBLED NEST BOX 300mm 260mm ENTRY PERCH < ATTACHED HERE 260mm 580mm Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre MATERIALS: + 12mm tanalised plywood + Galvanised screws 30mm (x39) Galvanised screws 20mm (x2 for access panel) DIMENSIONS: Top: 300 x 650mm Front: 245 x 580mm Back: 350 x 580mm Base: 260 x 580mm Ends: 260 x 260 x 300mm Door: 150 x 150mm Entrance & Access Holes: 100mm + + + TOP + 300x650mm + + + + + + + + BACK 350x580mm + + + + ACCESS + + FRONT + HOLE + 100x100 ENTRANCE 245x580mm HOLE END 100x100 END 260x260x300mm 260x260x300mm + + + + + + + + + + + ACCESS COVER 150x150mm + BASE + 260x580mm + + + + + Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre INSTRUCTIONS FOR RURU NEST BOX ASSEMBLY: Screw front and back onto inside edge of base (4 screws along each edge using pre-drilled holes). -

Tc & Forward & Owls-I-IX

USDA Forest Service 1997 General Technical Report NC-190 Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere Second International Symposium February 5-9, 1997 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Editors: James R. Duncan, Zoologist, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Department of Natural Resources Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB CANADA R3J 3W3 <[email protected]> David H. Johnson, Wildlife Ecologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA, USA 98501-1091 <[email protected]> Thomas H. Nicholls, retired formerly Project Leader and Research Plant Pathologist and Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN, USA 55108-6148 <[email protected]> I 2nd Owl Symposium SPONSORS: (Listing of all symposium and publication sponsors, e.g., those donating $$) 1987 International Owl Symposium Fund; Jack Israel Schrieber Memorial Trust c/o Zoological Society of Manitoba; Lady Grayl Fund; Manitoba Hydro; Manitoba Natural Resources; Manitoba Naturalists Society; Manitoba Critical Wildlife Habitat Program; Metro Propane Ltd.; Pine Falls Paper Company; Raptor Research Foundation; Raptor Education Group, Inc.; Raptor Research Center of Boise State University, Boise, Idaho; Repap Manitoba; Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada; USDI Bureau of Land Management; USDI Fish and Wildlife Service; USDA Forest Service, including the North Central Forest Experiment Station; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; The Wildlife Society - Washington Chapter; Wildlife Habitat Canada; Robert Bateman; Lawrence Blus; Nancy Claflin; Richard Clark; James Duncan; Bob Gehlert; Marge Gibson; Mary Houston; Stuart Houston; Edgar Jones; Katherine McKeever; Robert Nero; Glenn Proudfoot; Catherine Rich; Spencer Sealy; Mark Sobchuk; Tom Sproat; Peter Stacey; and Catherine Thexton. -

Birds New Zealand No. 11

No. 11 September 2016 Birds New Zealand The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NO. 11 SEPTEMBER 2016 Proud supporter of Birds New Zealand Proud supporter of 3 President’s Report Birds New Zealand 5 New Birdwatching Location Maps We are thrilled with our decision 7 Subantarctic Penguins’ Marathon ‘Migration’ to support Birds New Zealand. Fruzio’s aim is to raise awareness of the dedicated 8 Laughing Owl related to Morepork work of Birds New Zealand and to enable wider public engagement with the organisation. We have 9 Fiordland Crested Penguin Update re-shaped our marketing strategy and made a firm commitment of $100,000 to be donated over the 11 Ancient New Zealand Wrens course of the next 3 years. Follow our journey on: www.facebook/fruzio. 12 Are Hihi Firing Blanks? 13 Birding Places - Waipu Estuary PUBLISHERS Hugh Clifford Tribute Published on behalf of the members of the Ornithological Society of 14 New Zealand (Inc). P.O. Box 834, Nelson 7040, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] 15 Minutes of the 77th AGM Website: www.osnz.org.nz Editor: Michael Szabo, 6/238, The Esplanade, Island Bay, Wellington 6023. Phone: (04) 383 5784 16 Regional Roundup Email: [email protected] ISSN 2357-1586 (Print) ISSN 2357-1594 (Online) 19 Bird News We welcome advertising enquiries. Free classified ads are available to members at the editor’s discretion. Articles and illustrations related to birds, birdwatching or ornithology in New Zealand and the South Pacific region for inclusion in Birds New Zealand are welcome in electronic form, including news about about birds, COVER IMAGE members’ activities, bird studies, birding sites, identification, letters to the editor, Front cover: Fiordland Crested Penguin or Tawaki in rainforest reviews, photographs and paintings. -

Hawk-Owls and Allies Genus Ninox Hodgs

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 264-265. Order STRIGIFORMES: Owls Regarding the following nomina dubia, see under genus Aegotheles Vigors & Horsfield: Strix parvissima Ellman, 1861: Zoologist 19: 7465. Nomen dubium. Strix parvissima Potts, 1871: Trans. N.Z. Inst. 3: 68 – Rangitata River, Canterbury. Nomen dubium. Athene (Strix) parvissima Potts; Potts 1873, Trans. N.Z. Inst. 5: 172. Nomen dubium Family STRIGIDAE Leach: Typical Owls Strigidae Leach, 1819: Eleventh room. In Synopsis Contents British Museum 15th Edition, London: 64 – Type genus Strix Linnaeus, 1758. Subfamily BUBONINAE Vigors: Hawk-owls and Allies Bubonina Vigors, 1825: Zoological Journal 2: 393 – Type genus Bubo Dumeril, 1805. Genus Ninox Hodgson Ninox Hodgson, 1837: Madras Journ. Lit. Sci. 5: 23 – Type species (by original designation) Ninox nipalensis Hodgson = Ninox scutulata lugubris (Tickell). Hieracoglaux Kaup, 1848: Isis von Oken, Heft 41: col. 768 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Falco connivens Latham = Ninox connivens (Latham). As a subgenus of Ninox. Spiloglaux Kaup, 1848: Isis von Oken, Heft 41: col. 768 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Strix boobook Latham = Ninox boobook (Latham). As a subgenus of Ninox. Ieraglaux Kaup, 1852: in Jardine, Contrib. Ornith.: 107 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Falco connivens Latham = Ninox connivens (Latham). Rhabdoglaux Bonaparte, 1854: Revue Mag. Zool. 2 (2): 543 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Athene humeralis Bonaparte = Ninox rufa humeralis (Bonaparte). -

Observations on the Biology of the Powerful Owl Ninox Strenua in Southern Victoria by E.G

VOL. 16 (7) SEPTEMBER 1996 267 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1996, 16, 267-295 Observations on the Biology of the Powerful Owl Ninox strenua in Southern Victoria by E.G. McNABB, P.O. \IJ~~ 408, Emerald, Victoria 3782 . \. Summary A pair of Powerful Owls Ninox strenua was studied at each of two sites near Melbourne, Victoria, for three years (1977-1979) and 15 years (1980-1994 inclusive) respectively, by diurnal and nocturnal observation. Home ranges were.mapped, nest sites characterised and breeding chronology and success monitored. General observations at these and eight other sites, of roosting, courting, nesting, parental and juvenile behaviour, fledgling mortality, hunting, interspecific conflicts, bathing, and camouflage posing, are presented. The regularly used parts of the home ranges of two pairs were each estimated as c. 300 ha, although for one pair this applied only to the breeding season. One pair used seven nest trees in 15 years, commonly two or three times each (range 1-4 times) over consecutive years before changing trees. Nest-switching may have been encouraged by human inspection of hollows. Nest entrances were 8-40 m (mean 22 m) above ground. The owls clearly preferred the larger and older trees (estimated 350-500+ years old), beside permanent creeks rather than seasonal streams, and in gullies or on sheltered aspects rather than ridges. Laying dates were spread over a month from late May, with a peak in mid June. The breeding cycle occupied three months from laying to fledging, of which the nestling period lasted 8-9 weeks. Breeding success was 1.4 young per pair per year and 94% nest success; early nests in gullies were more successful than late nests on slopes. -

Pre–Release Training of Juvenile Little Owls Athene Noctua to Avoid Predation

Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 34.2 (2011) 389 Pre–release training of juvenile little owls Athene noctua to avoid predation R. Alonso, P. Orejas, F. Lopes & C. Sanz Alonso, R., Orejas, P., Lopes, F. & Sanz, C., 2011. Pre–release training of juvenile little owls Athene noctua to avoid predation. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 34.2: 389–393. Abstract Pre–release training of juvenile little owls Athene noctua to avoid predation.— Anti–predator training of juvenile little owls was tested in a sample of recovered owls raised in captivity in Brinzal Owl Rescue Center (Madrid, Spain). Mortality caused by predators has been described previously in released individuals. Nine little owls were conditioned during their development to a naturalized goshawk and a large live rat, whose presence was paired to the owl’s alarm call. All nine owls and seven non–trained individuals were then released during the late summer and autumn and radio–tracked for six weeks to test their survival. In total 71.4% of the trained owls survived while only the 33.3% of the untrained group were alive at the end of week six. The only cause of death that was detected was predation. Antipredator training, therefore, seems to be beneficial in maximizing survival after the release of juvenile little owls. Key words: Little owl, Athene noctua, Reintroduction, Release, Survival, Antipredator training. Resumen Entrenamiento antes de la liberación en mochuelos europeos Athene noctua para evitar su depredación.— Un entrenamiento sobre mochuelos juveniles para evitar la depredación, se ha testado en una muestra de ejem- plares recuperados y criados en el Centro de Recuperación de Rapaces Nocturnas Brinzal (Madrid, España). -

Approved Recovery Plan for Large Forest Owls

Approved NSW Recovery Plan Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls Powerful Owl Sooty Owl Masked Owl Ninox strenua Tyto tenebricosa Tyto novaehollandiae October 2006 Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW), 2006. This work is copyright, however, material presented in this plan may be copied for personal use or educational purposes, providing that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Apart from this and any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from DEC. This plan should be cited as follows: Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) (2006). NSW Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls: Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua), Sooty Owl (Tyto tenebricosa) and Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae) DEC, Sydney. For further information contact: Large Forest Owl Recovery Coordinator Biodiversity Conservation Unit Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) PO Box A290 Sydney South NSW 1232 Published by: Department of Environment and Conservation NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 1 74137 995 4 DEC 2006/413 October 2006 Cover photographs: Powerful Owl, R. Jackson, Sooty Owl, D. Hollands and Masked Owl, M. Todd. Approved Recovery Plan for Large Forest Owls Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls Executive Summary This document constitutes the formal New South Wales State recovery plan for the three large forest owls of NSW - the Powerful Owl Ninox strenua (Gould), Sooty Owl Tyto tenebricosa (Gould) and Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae (Stephens). -

A Preliminary Risk Assessment of Cane Toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT

supervising scientist 164 report A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park RA van Dam, DJ Walden & GW Begg supervising scientist national centre for tropical wetland research This report has been prepared by staff of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist (eriss) as part of our commitment to the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research Rick A van Dam Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, Locked Bag 2, Jabiru NT 0886, Australia (Present address: Sinclair Knight Merz, 100 Christie St, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia) David J Walden Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia George W Begg Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia This report should be cited as follows: van Dam RA, Walden DJ & Begg GW 2002 A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT The Supervising Scientist is part of Environment Australia, the environmental program of the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Supervising Scientist Environment Australia GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 Australia ISSN 1325-1554 ISBN 0 642 24370 0 This work is copyright Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Supervising Scientist Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction -

OWLS of OHIO C D G U I D E B O O K DIVISION of WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O

OWLS OF OHIO c d g u i d e b o o k DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O Owls have longowls evoked curiosity in In the winter of of 2002, a snowy ohio owl and stygian owl are known from one people, due to their secretive and often frequented an area near Wilmington and two Texas records, respectively. nocturnal habits, fierce predatory in Clinton County, and became quite Another, the Oriental scops-owl, is behavior, and interesting appearance. a celebrity. She was visited by scores of known from two Alaska records). On Many people might be surprised by people – many whom had never seen a global scale, there are 27 genera of how common owls are; it just takes a one of these Arctic visitors – and was owls in two families, comprising a total bit of knowledge and searching to find featured in many newspapers and TV of 215 species. them. The effort is worthwhile, as news shows. A massive invasion of In Ohio and abroad, there is great owls are among our most fascinating northern owls – boreal, great gray, and variation among owls. The largest birds, both to watch and to hear. Owls Northern hawk owl – into Minnesota species in the world is the great gray are also among our most charismatic during the winter of 2004-05 became owl of North America. It is nearly three birds, and reading about species with a major source of ecotourism for the feet long with a wingspan of almost 4 names like fearful owl, barking owl, North Star State. -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help.