Table of Contents the Quakers of East Fairhope ������������������������������������������ 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline 1864

CIVIL WAR TIMELINE 1864 January Radical Republicans are hostile to Lincoln’s policies, fearing that they do not provide sufficient protection for ex-slaves, that the 10% amnesty plan is not strict enough, and that Southern states should demonstrate more significant efforts to eradicate the slave system before being allowed back into the Union. Consequently, Congress refuses to recognize the governments of Southern states, or to seat their elected representatives. Instead, legislators begin to work on their own Reconstruction plan, which will emerge in July as the Wade-Davis Bill. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/reconstruction/states/sf_timeline.html] [http://www.blackhistory.harpweek.com/4Reconstruction/ReconTimeline.htm] Congress now understands the Confederacy to be the face of a deeply rooted cultural system antagonistic to the principles of a “free labor” society. Many fear that returning home rule to such a system amounts to accepting secession state by state and opening the door for such malicious local legislation as the Black Codes that eventually emerge. [Hunt] Jan. 1 TN Skirmish at Dandridge. Jan. 2 TN Skirmish at LaGrange. Nashville is in the grip of a smallpox epidemic, which will carry off a large number of soldiers, contraband workers, and city residents. It will be late March before it runs its course. Jan 5 TN Skirmish at Lawrence’s Mill. Jan. 10 TN Forrest’s troops in west Tennessee are said to have collected 2,000 recruits, 400 loaded Wagons, 800 beef cattle, and 1,000 horses and mules. Most observers consider these numbers to be exaggerated. “ The Mississippi Squadron publishes a list of the steamboats destroyed on the Mississippi and its tributaries during the war: 104 ships were burned, 71 sunk. -

High Court of Congress: Impeachment Trials, 1797-1936 William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Popular Media Faculty and Deans 1974 High Court of Congress: Impeachment Trials, 1797-1936 William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "High Court of Congress: Impeachment Trials, 1797-1936" (1974). Popular Media. 267. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media/267 Copyright c 1974 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media High Court of Congress: Impeachment Trials, 1797-1936 by William F. Swindler Twelve "civil officers" of the United States have tacle, appear to have rested more on objective (and been subjected to trials on impeachment articles perhaps quasi-indictable) charges. in the Senate. Both colorful and colorless figures The history of impeachment as a tool in the struggle have suffered through these trials, and the nation's for parliamentary supremacy in Great Britain and the fabric has been tested by some of the trials. History understanding of it at the time of the first state constitu- shows that impeachment trials have moved from tions and the Federal Convention of 1787 have been barely disguised political vendettas to quasi-judicial admirably researched by a leading constitutional his- proceedings bearing the trappings of legal trials. torian, Raoul Berger, in his book published last year, Impeachment: Some Constitutional Problems. Like Americans, Englishmen once, but only once, carried the political attack to; the head of state himself. In that encounter Charles I lost his case as well as his head. The decline in the quality of government under the Com- monwealth thereafter, like the inglorious record of MPEACHMENT-what Alexander Hamilton called American government under the Reconstruction Con- "the grand inquest of the nation"-has reached the gresses, may have had an ultimately beneficial effect. -

Civil War Chronological History for 1864 (150Th Anniversary) February

Civil War Chronological History for 1864 (150th Anniversary) February 17 Confederate submarine Hunley sinks Union warship Housatonic off Charleston. February 20 Union forces defeated at Olustee, Florida (the now famous 54th Massachusetts took part). March 15 The Red River campaign in Louisiana started by Federal forces continued into May. Several battles eventually won by the Confederacy. April 12 Confederates recapture Ft. Pillow, Tennessee. April 17 Grant stops prisoner exchange increasing Confederate manpower shortage. April 30 Confederates defeat Federals at Jenkins Ferry, Arkansas and force them to withdraw to Little Rock. May 5 Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia. May 8‐21 Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia (heaviest battle May 12‐13). May 13 Battle at Resaca, Georgia as Sherman heads toward Atlanta. May 15 Battle of New Market, Virginia. May 25 Four day battle at New Hope Church, Georgia. June 1‐3 Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia. Grants forces severely repulsed. June 10 Federals lose at Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi. June 19 Siege of Petersburg, Virginia by Grant’s forces. June 19 Confederate raider, Alabama, sunk by United States warship off Cherbourg, France. June 27 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia. July 12 Confederates reach the outskirts of Washington, D.C. but are forced to withdraw. July 15 Battle of Tupelo, Mississippi. July 20 Battle of Peachtree Creek, Georgia. July 30 Battle of the Crater, Confederates halt breakthrough. August 1 Admiral Farragut wins battle of Mobile Bay for the Union. September 1 Confederates evacuate Atlanta. September 2 Sherman occupies Atlanta. September 4 Sherman orders civilians out of Atlanta. September 19 Battle at Winchester, Virginia. -

Free All Americans in Honolulu Murder

‘ > 'Z- .H ' • d a i l t cnoDLAnoif f n ttw MoBth « f Apm, 1 9 » 5,509 MMnber «f Audit B o tm u of carenluttoB* (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, MAY 5, 1932. VOL. U ., NO. 185. idM iilled Advertisliis oo Psgj 12.). ACCORD NO NEARER Chicago’s Public Enemy No. 1, Prison-bound FREE ALL AMERICANS AMONG DEMOCRATS IN HONOLULU MURDER Smith Followers In State'VERSAILLES PACT Sentenced To Ten Years In Commons in Uproar Gather Bot Name No Can-1 BLAMED FOR WOES Surprise Court Session didate For Chairman F or; — Over Allegiance Oath They Are Immediately Ex-Crown Prince of Germany Coming Parley. London, May 5.—(AP)—The ..the British government could not Granted Conmnitation of House of Commons worked its e lf' for the present do more than call Asks Americans To Try into an upro' over the Irish ques attention to the violation of the Sentence To One flour By By AflMNteted Pretn tion today when Cieottrey Mander, treaty of 1921 Involved In the Free National Liberal from Wolverhamp State’s unilateral action. A |;mtbeiiDg of Democrats, most And Understand Comitry. ton, asked the secretary for domin The question was framed thus: Is Governor— Move For Out of them delegate* to the party'* ions whether the government would the government prepared to submit state convention in Hartford May submit the oath o. a’l^iance to a the oath of allegiance in dispute be (Ckjpyright 1932 by A. P.) right Pardon Pressed— To 16 and 17, and all aupporter* of the judicial tribunal. -

American Civil War

American Civil War Major Battles & Minor Engagements 1861-1865 1861 ........ p. 2 1862 ........ p. 4 1863 ........ p. 9 1864 ........ p. 13 1865 ........ p. 19 CIVIL WAR IMPRESSIONIST ASSOCIATION 1 Civil War Battles: 1861 Eastern Theater April 12 - Battle of Fort Sumter (& Fort Moultie), Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The bombardment/siege and ultimate surrender of Fort Sumter by Brig. General P.G.T. Beauregard was the official start of the Civil War. https://www.nps.gov/fosu/index.htm June 3 - Battle of Philippi, (West) Virginia A skirmish involving over 3,000 soldiers, Philippi was the first battle of the American Civil War. June 10 - Big Bethel, Virginia The skirmish of Big Bethel was the first land battle of the civil war and was a portent of the carnage that was to come. July 11 - Rich Mountain, (West) Virginia July 21 - First Battle of Bull Run, Manassas, Virginia Also known as First Manassas, the first major engagement of the American Civil War was a shocking rout of Union soldiers by confederates at Manassas Junction, VA. August 28-29 - Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina September 10 - Carnifax Ferry, (West) Virginia September 12-15 - Cheat Mountain, (West) Virginia October 3 - Greenbrier River, (West) Virginia October 21 - Ball's Bluff, Virginia October 9 - Battle of Santa Rosa Island, Santa Rosa Island (Florida) The Battle of Santa Rosa Island was a failed attempt by Confederate forces to take the Union-held Fort Pickens. November 7-8 - Battle of Port Royal Sound, Port Royal Sound, South Carolina The battle of Port Royal was one of the earliest amphibious operations of the American Civil War. -

Battle of Mobile Bay

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM NY NY HistoricalSociety - dson PaintingbyDavi J.O. INTRODUCTION Students of the Civil War find no shortage of material regarding the battle of Mobile Bay. There are numerous stirring accounts of Farragut’s dramatic damning of the “torpedoes” and the guns of Fort Morgan, and of the gallant but futile resistance offered by the CSS Tennessee to the entire Union Fleet. These accounts range from the reminiscences of participants to the capably analyzed reappraisals by Centennial historians. It is particularly frustrating then, to find hardly any adequate description of the land campaign for Mobile in the general accounts of the War between the States. A few lines are usually deemed sufficient by historians to relate this campaign to reduce the last major confederate stronghold in the West, described as the best fortified city in the Confederacy by General Joseph E. Johnston, and which indeed did not fall until after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. It fell then to an attacking Federal force of some 45,000 troops, bolstered by a formidable siege train and by the support of the Federal Navy. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, to give one example, devotes 33 well illustrated pages to the battle of Mobile Bay, but allows only one page for the land CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM operations of 1865 ! The following account is written as a small contribution to the Civil War Centennial and is intended to provide a brief but reasonably comprehensive account of the campaign. Operations will from necessity be viewed frequently from the positions of the attacking Federal forces. -

36Th & 51St VA Infantry Engagements with Civil War Chronology, 1860

Grossclose Brothers in Arms: 36th and 51st Virginia Infantry Engagements with a Chronology of the American Civil War, 1860-1865 Engagements 36th VA Infantry 51st VA Infantry (HC Grossclose, Co G-2nd) (AD & JAT Grossclose, Co F) Civil War Chronology November 1860 6 Lincoln elected. December 1860 20 South Carolina secedes. 26 Garrison transferred from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter. January 1861 9 Mississippi secedes; Star of the West fired upon 10 Florida Secedes 11 Alabama secedes. 19 Georgia secedes. 21 Withdrawal of five Southern members of the U.S.Senate: Yulee and Mallory of Florida, Clay and Fitzpatrick of Alabama, and Davis of Mississippi. 26 Louisiana secedes. 29 Kansas admitted to the Union as a free state. February 1861 1 Texas convention votes for secession. 4 lst Session, Provisional Confederate Congress, convenes as a convention. 9 Jefferson Davis elected provisional Confederate president. 18 Jefferson Davis inaugurated. 23 Texas voters approve secession. March 1861 4 Lincoln inaugurated; Special Senate Session of 37th Congress convenes. 16 lst Session, Provisional Confederate Congress, adjourns. 28-Special Senate Session of 37th Congress adjourns. April 1861 12 Bombardment of Fort Sumter begins. 13 Fort Sumter surrenders to Southern forces. 17 Virginia secedes. 19 6th Massachusetts attacked by Baltimore mob; Lincoln declares blockade of Southern coast. 20 Norfolk, Virginia, Navy Yard evacuated. 29 2nd Session, Provisional Confederate Congress, convenes; Maryland rejects secession. May 1861 6 Arkansas secedes; Tennessee legislature calls for popular vote on secession. 10 Union forces capture Camp Jackson, and a riot follows in St. Louis. 13 Baltimore occupied by U.S. troops. 20 North Carolina secedes. -

Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment As Justice of the Peace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Winter 1996 Article 2 1996 Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace. David F. Forte Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation David F. Forte, Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace., 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 349 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MARBURY'S TRAVAIL: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND WILLIAM MARBURY'S APPOINTMENT AS JUSTICE OF THE PEACE* David F. Forte** * The author certifies that, to the best of his ability and belief, each citation to unpublished manuscript sources accurately reflects the information or proposition asserted in the text. ** Professor of Law, Cleveland State University. A.B., Harvard University; M.A., Manchester University; Ph.D., University of Toronto; J.D., Columbia University. After four years of research in research libraries throughout the northeast and middle Atlantic states, it is difficult for me to thank the dozens of people who personally took an interest in this work and gave so much of their expertise to its completion. I apologize for the inevita- ble omissions that follow. My thanks to those who reviewed the text and gave me the benefits of their comments and advice: the late George Haskins, Forrest McDonald, Victor Rosenblum, William van Alstyne, Richard Aynes, Ronald Rotunda, James O'Fallon, Deborah Klein, Patricia Mc- Coy, and Steven Gottlieb. -

Vintage Times

August 2019 VINTAGE TIMES Vintage Park Apartments, 810 East Van Buren, Lenox, IA 50851 Vintageparkapts.com 641-333-2233 Unlikely Medal of Honor Recipient: and killed Key in broad daylight across the street from the U.S. Capital building in 1859; one can Dan Sickles estimate the salacious effect the murder had on Washington’s social and political climate. The trial By: itself was colorful and notable due to the steamy Doug Junker storylines and the fact that Sickles was acquitted due to his legal team’s use of the “temporary insanity” defense, which marked the first successful The study of the U.S. Civil War has long utilization of the defense in U.S. history. At the been a passion of mine. For me the Civil War was start of the Civil War, Sickles, likely motivated by a culmination of extraordinary times and the need to redeem his reputation and escape the fascinating characters that add color and life to stigma of his social and political problems, gained a events that happened over a 150 years ago. I have political appointment as a general in the U.S. Army always felt that understanding the individuals who and recruited a number of New York regiments that fought the war allowed me to better understand the became known as the Excelsior Brigade. Despite conflict itself and therefore, gain an understanding his complete lack of military experience Sickles of the nation that rose from the ashes of a war that was involved in several prominent battles in the claimed the lives of over 600,000 American eastern theater before leading his men towards citizens. -

THE WORLD of LAFAYETTE SQUARE Sites Around the Square

THE WORLD OF LAFAYETTE SQUARE Lafayette Square is a seven-acre public park located directly north of the White House on H Street between 15th and 17th Streets, NW. The Square and the surrounding structures were designated a National Historic Landmark District in 1970. Originally planned as part of the pleasure grounds surrounding the Executive Mansion, the area was called "President's Park". The Square was separated from the White House grounds in 1804 when President Jefferson had Pennsylvania cut through. In 1824, the Square was officially named in honor of General Lafayette of France. A barren common, it was neglected for many years. A race course was laid out along its west side in 1797, and workmen's quarters were thrown up on it during the construction of the White House in the 1790s. A market occupied the site later and, during the War of 1812, soldiers were encamped there. Lafayette Park has been used as a zoo, a slave market, and for many political protests and celebrations. The surrounding neighborhood became the city's most fashionable 19th century residential address. Andrew Jackson Downing landscaped Lafayette Square in 1851 in the picturesque style. (www.nps.gov) Historian and novelist Henry Adams on Washington, D.C. 1868: “La Fayette Square was society . one found all one’s acquaintances as well as hotels, banks, markets, and national government. Beyond the Square the country began. No rich or fashionable stranger had yet discovered the town. No literary of scientific man, no artist, no gentleman without office or employment has ever lived there. -

Civil War Collection, 1860-1977

Civil War collection, 1860-1977 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Civil War collection, 1860-1977 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 20 Extent: 10 linear feet (23 boxes), 7 bound volumes (BV), 7 oversized papers boxes and 29 oversized papers folders (OP), 4 microfilm reels (MF), and 1 framed item (FR) Abstract: The Civil War collection is an artificial collection consisting of both contemporary and non-contemporary materials relating to the American Civil War (1861-1865). Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Additional Physical Form The Robert F. Davis diaries in Subseries 1.1 are also available on microfilm. Source Various sources. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Civil War collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Reprocessed by Susan Potts McDonald, 2013. This collection contains material that was originally part of Miscellaneous Collections A-D, F, and H-I. In 2017, these collections were discontinued and the contents dispersed amongst other collections by subject or provenance to improve accessibility. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Civil War collection Manuscript Collection No. 20 Sheet music in this collection was formerly part of an unaccessioned collection of sheet music that was transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2019. -

Port of Mobile Directory

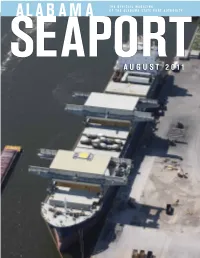

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE A L A B A M A OF The ALABAMA STATE PORT AUTHORITY SEAPORT AUGUST 20 11 Alabama Seaport PuBlishED continuOuSly since 1927 • august 2011 On The Cover: The mV STAR kIRKEnES docks at the aSPa’s Pier D2. The kIRKEnES is Seabulk Towing: Providing Service the first vessel in the new west Coast of South america route. Excellence Through Safety 4 10 Alabama State Port Authority P.O. Box 1588, Mobile, Alabama 36633, USA P: 251.441.7200 • F: 251.441.7216 • asdd.com Contents James K. Lyons, Director, CEO grieg Star Shipping Begins additional Service in mobile ..........................4 Larry R. Downs, Secretary-Treasurer/CFO grieg Star Shipping Celebrates 50 years ......................................................8 Financial SerVices Larry Downs, Secretary/Treasurer 251.441.7050 Bringing Cutting-Edge Technology to the People of alabama ................10 Linda K. Paaymans, Sr. Vice President, Finance 251.441.7036 Port of mobile lands 2012 rICa annual meeting and Conference ...... 13 COmptrOllEr Pete Dranka 251.441.7057 Information TechnOlOgy Stan Hurston, manager 251.441.7017 meet alabama’s newest warrior: greg Canfield, human Resources Danny Barnett, manager 251.441.7004 Risk managEmEnT Kevin Malpas, manager 251.441.7118 Director of the alabama Development Office .............................................15 InTErnal auditor Avito DeAndrade 251.441.7210 In memoriam: murrell kearns....................................................................... 20 MarketinG Port Calls: Freedom rides museum Commemorates Struggle Judith Adams, Vice President 251.441.7003 Sheri Reid, manager, Public affairs 251.441.7001 for Peace and Equality in the South ........................................................... 22 Seabulk Towing is an established leader in harbor ship assist operations Pete O’Neal, manager, real Estate 251.441.7123 John Goff, manager, Theodore Operations 251.443.7982 Currents ...........................................................................................................