Reading and Writing The" Lived-Through Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Beauty

Black Beauty Black Beauty The story Black Beauty was a handsome horse with one white foot and a white star on his forehead. His life started out on a farm with his mother, Duchess, who taught him to be gentle and kind and to never bite or kick. When Black Beauty was four years old, he was sold to Squire Gordon of Birtwick Park. He went to live in a stable where he met and became friends with two horses, Merrylegs and Ginger. Ginger started life with a cruel owner who used a whip on her. She treated her cruel owner with the lack of respect he deserved. When she went to live at Birtwick Park, Ginger still kicked and bit, but she grew happier there. The groom at Birtwick Park, John, was very kind and never used a whip. Black Beauty saved the lives of Squire Gordon and John one stormy night when they tried to get him to cross a broken bridge. The Squire was very grateful and loved Black Beauty very much. One night a foolish young stableman left his pipe burning in the hay loft where Black Beauty and Ginger were staying. Squire Gordon’s young stableboy, James, saved Black Beauty and Ginger from the burning stable. The Squire and his wife were very grateful and proud of their young stableboy. James got a new job and left Birtwick Park and a new stableboy, Joe Green, took over. Then, one night Black Beauty nearly died because of Joe’s lack of experience and knowledge. The Gordons had to leave the country because of Mrs Gordon’s health and sold Black Beauty to Lord Westerleigh at Earlshall Park. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

Cham : the Best Comic Strips and Graphic Novelettes, 1839-1862 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHAM : THE BEST COMIC STRIPS AND GRAPHIC NOVELETTES, 1839-1862 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Kunzle | 538 pages | 30 May 2019 | University Press of Mississippi | 9781496816184 | English | Jackson, United States Cham : The Best Comic Strips and Graphic Novelettes, 1839-1862 PDF Book A chapter on fashionable ball dress is also included. Recensioner i media. DC, As mentioned in the description, this Sanjulian book was a Kickstarter project. He is one much deserving, at last, of this first account of his huge oeuvre as a caricaturist. Because the process took so long, the voting window for comic book professionals is shorter, but the awards are still going to be given out in July. Halfway the serialisation the originals were clumsily redrawn by a staff member possibly Cham? L'Exposition de Londres by Cham Book 12 editions published between and in French and held by 43 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. During his lifetime he was one of the most popular French cartoonists. Rows: Columns:. The tall man holding a woman with an umbrella's hand is a self-caricature. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. Yet beneath the surface, tensions linger sixteen years after a failed rebellion. Presenting the history of corsetry and body sculpture, this edition shows how the relationship between fashion and sex is closely bound up with sexual self-expression. In several scenes Cham introduces concepts like close-ups, wide shots, jumpcuts and different perspectives. Since his back catalogue is so immense, few art historians have taken time to explore and study his work in its entirety. -

Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’S Tale

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2016 Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Meister, L. (2016). Freakish, feathery, and foreign: Language of otherness in the Squire's tale. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 12, 48-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Freakish, Feathery, and Foreign: Language of Otherness in the Squire’s Tale Laurel Meister hough setting a standard for English literature in the centuries to follow, The Canterbury Tales was anything but standard in its Town time. Written in a Middle English vernacular that was only recently being used for poetry, and filtered through the minds and mouths of the wackiest of characters, Geoffrey Chaucer’s storytelling explores the Other: an unfamiliar realm set apart from the norm. One of the tales whose lan- guage engages with the Other, the Squire’s Tale features a magical ring al- lowing its wearer to understand any bird “And knowe his menyng openly and pleyn / and answere hym in his langage again,” a rhyme that repeats like an incantation throughout the tale.1 Told from the perspective of a young and inexperienced Squire, the story has all the makings of a chivalric fairy- tale—including a knight and a beautiful princess—with none of the finesse. -

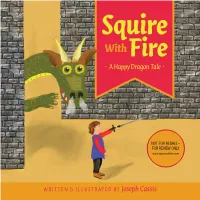

NOT for RESALE - for REVIEW ONLY Squire with Fire · a Happy Dragon Tale ·

NOT FOR RESALE - FOR REVIEW ONLY www.squirewithfire.com Squire With Fire · A Happy Dragon Tale · WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED BY Joseph Cassis “Grandpa, what is that?” Mac asked as the curious young child pointed to Grandfather’s wrinkled but strong hand. 1 “You mean this gold ring?” responded Grandpa, who was dressed in his favorite royal purple shirt. He proudly curled his hand into a tight fist to show Mac his gold ring better. Mac nodded. “Yep, it’s so shiny.” Grandpa leaned into Mac and said in a soft voice, “My father gave it to me and his father gave it to him and his grandfather gave it to him. Well, you get the idea. It was a very long time ago. This special family ring is over 600 years old.” Mac’s big brown eyes widened, staring at the “Well, it’s just not that easy, Mac. You must gleaming ring. “Wow, like you, Grandpa?” show me that you have all the qualities of a squire,” said Grandpa. Grandpa chuckled. “Well, no. I am a bit younger than 600. When they were seven years old, Mac looked puzzled and stared at Grandpa. “A our ancestors competed to be squires. They squire? What’s a squire?” learned the ways of being a knight, and then Grandpa answered with a slight grin, “A squire is if they proved they were worthy, they became young person who is a knight’s helper.” squires at fourteen and received this beautiful gold ring.” Mac smiled. “I know. You mean he helps knights fight dragons?” “Oh,” Mac said, excitedly. -

BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- the THEATRE MUSIC of DANIEL PURCELL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 6 9 -4 8 4 2 BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL. (VOLUMES I AND II). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Robert Squire Barstow 1969 - THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL .DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for_ the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Squire Barstow, B.M., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Department of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the Graduate School of the Ohio State University and to the Center of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, whose generous grants made possible the procuring of materials necessary for this study, the author expresses his sincere thanks. Acknowledgment and thanks are also given to Dr. Keith Mixter and to Dr. Mark Walker for their timely criticisms in the final stages of this paper. It is to my adviser Dr. Norman Phelps, however, that I am most deeply indebted. I shall always be grateful for his discerning guidance and for the countless hours he gave to my problems. Words cannot adequately express the profound gratitude I owe to Dr. C. Thomas Barr and to my wife. Robert S. Barstow July 1968 1 1 VITA September 5, 1936 Born - Gt. Bend, Kansas 1958 .......... B.M. , ’Port Hays Kansas State College, Hays, Kansas 1958-1961 .... Instructor, Goodland Public Schools, Goodland, Kansas 1961-1964 .... National Defense Graduate Fellow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963............ M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio __ 1964-1966 ... -

Superhero Origins As a Sentence Punctuation Exercise

Superhero Origins as a Sentence Punctuation Exercise The Definition of a Comic Book Superhero A comic book super hero is a costumed fictional character having superhuman/extraordinary skills and has great concern for right over wrong. He or she lives in the present and acts to benefit all mankind over the forces of evil. Some examples of comic book superheroes include: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, and Plastic Man. Each has a characteristic costume which distinguishes them from everyday citizens. Likewise, all consistently exercise superhuman abilities for the safety and protection of society against the forces of evil. They ply their gifts in the present-contemporary environment in which they exist. The Sentence Punctuation Assignment From earliest childhood to old age, the comics have influenced reading. Whether the Sunday comic strips or editions of Disney’s works, comic book art and narratives have been a reading catalyst. Indeed, they have played a huge role in entertaining people of all ages. However, their vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall appropriateness as a reading resource is often in doubt. Though at times too “graphic” for youth or too “childish” for adults, their use as an educational resource has merit. Such is the case with the following exercise. Superheroes as a sentence punctuation learning toll. Among the most popular of comic book heroes is Superman. His origin and super-human feats have thrilled comic book readers, theater goers, and television watchers for decades. However, many other comic book superheroes exist. Select one from those superhero origin accounts which follow and compose a four paragraph superhero origin one page double-spaced narative of your selection. -

{FREE} Batman & Robin Vol. 2 Batman Vs. Robin

BATMAN & ROBIN VOL. 2 BATMAN VS. ROBIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Grant Morrison | 168 pages | 22 Nov 2011 | DC Comics | 9781401232719 | English | United States Batman & Robin Vol. 2 Batman vs. Robin PDF Book I liked part 2 more than the first arc in here. Robin [January ] Indexer Notes Introduction to the bonus section with illustration. It goes about as well as you might expect. I remember the Batman army that Darkseid creates, because they're insane and can't be controlled. Read more Read less. Still, it feels like it's mostly setting the stage for Bruce Wayne's inevitable return more than anything else. Batman R. Be the first. Scott Hanna Inker ,. After 21 minutes of driving in silence, they were back in the Batcave , and Batman ordered him to get out of the car and go to bed. About Grant Morrison. Is Morrison practicing suspense and two-plot storytelling all of a sudden? Cover thumbnails are used for identification purposes only. Blackest Knight is ho-hum. Your rating has been recorded. I didn't care to see Dick working with Squire and Knight. At first everyone thought Bruce Wayne to be dead except for Tim Drake. Batman and Robin 13 variant. It makes his story so sad. Next page. Oct 03, Gavin rated it liked it Shelves: comics. Write a review Rate this item: 1 2 3 4 5. Categories :. You are commenting using your Twitter account. God, I love her! I am ready for more Batman and Robin stories both from the old and new continuity! Anyway, the Batman armour apparently can't take a shovel to the chest, despite the fact that it took a bullet last volume. -

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales Mr. Cline Marshall High School Western Civilization II Unit Two FA * The Canterbury Tales • Background • In this part, we'll be studying one of the most renowned pieces of English literature, The Canterbury Tales. • In this collection of stories written by Geoffrey Chaucer, we meet a colorful group of 29 travelers making a religious pilgrimage from London to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. • Along their journey, their host engages them in a storytelling contest with a free meal as the prize. • However, we soon find the Canterbury Tales are more about the storytellers themselves than they are about the tales they weave. • Before we get to Chaucer's eclectic group of characters, let's look at the times in which he wrote. • The Canterbury Tales were written in the late 14th century, a time in which people began to question the medieval ideas of Church power and Church purity as well as the societal roles of old class systems. * The Canterbury Tales • Background • These ideas were being traded in for the Renaissance, a word that literally means rebirth. • The Renaissance was a period of cultural revolution in terms of art, religion, and politics. • During this era, people began throwing off the old ideas of power and authority in exchange for the personal freedoms found in the ancient cultures of Greece and Rome. • This revolution of sorts began in Italy. However, well-traveled men like England's Geoffrey Chaucer soon carried it over the Alps and into the realms of Northern Europe. • Themes of the Tales • The Canterbury Tales is an excellent example of cultural diffusion, or the spreading out of ideas from one central point (Italy) to another (England). -

Country Squire in the White House Country Squire in the White House

COUNTRY SQUIRE IN THE WHITE HOUSE COUNTRY SQUIRE IN THE WHITE HOUSE By John T. Flynn Doubleday, Doran and Company, Inc. NEW YORK 1940 PRINTED AT THE Country Lite Press, GARDEN CITY, N. Y., U. S. A. CL COPYRIGHT, 1940 BY DOUBLEDAY, DORAN & COMPANY, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A Warning THIS IS AN ELECTION YEAR—a year of campaign hoo\s. But this is not one. It is the considered opinion of one man only who maizes it his business to \eep out of the camps of politicians. The writer who sets up as a commentator on public affairs should keep out of party organizations. It is diffi- cult enough to thin\ straight without fouling the ma- chinery with partisan emotions. The writer who joins the camp of a political leader ceases to be an honest observer. He becomes an agent. But a commentator does have opinions. I have mine. For years 1 was the kind of Democrat who voted for can- didates li\e Bryan and Wilson and Roosevelt in 1932. I was not the kind who voted for Parker or John W. Davis. I believe I may lay claim to being a liberal, who is well left of center, who thinks that the capitalist system may well be doomed through the unwillingness of its own defenders to do the things necessary to save it, but who also believes that its collapse in this country now would be the worst of all calamities. It is in the light of these views that whatever bias appears in this boo\ originates. -

Batman and the Superhero Fairytale: Deconstructing a Revisionist Crisis

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2013 Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2013 Travis John Landhuis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Landhuis, Travis John, "Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis" (2013). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 34. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/34 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by TRAVIS JOHN LANDHUIS 2013 All Rights Reserved BATMAN AND THE SUPERHERO FAIRYTALE: DECONSTRUCTING A REVISIONIST CRISIS An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa December 2013 ABSTRACT Contemporary superhero comics carry the burden of navigating historical iterations and reiterations of canonical figures—Batman, Superman, Green Lantern et al.—producing a tension unique to a genre that thrives on the reconstruction of previously established narratives. This tension results in the complication of authorial and interpretive negotiation of basic principles of narrative and structure as readers and producers must seek to construct satisfactory identities for these icons. Similarly, the post-modern experimentation of Robert Coover—in Briar Rose and Stepmother—argues that we must no longer view contemporary fairytales as separate (cohesive) entities that may exist apart from their source narratives. -

To Whom It May Concern by Aurin Squire Agent: Jonathan Mills

To Whom It May Concern By Aurin Squire Agent: Jonathan Mills PARADIGM 360 Park Avenue South, 16th Floor New York, NY. 10010 [email protected] T: (212) 897-6400 Author contact: Aurin Squire (786) 506-1677 [email protected] 2 CHARACTERS 1. Lorenzo Lafarhoff – 15-year-old rural boy 2. Maurice Creely – 20-year-old soldier STORY To Whom It May Concern is an epistolary play about a 15- year-old boy who tries to seduce a military soldier through a series of letters. When Lorenzo pretends to be a young woman their romance takes off until one night Maurice decides to visit his lady-in-waiting. To Whom is a bittersweet comedy. NOTES ON STAGING When characters write letters, e-mails or instant messages, the act should be performed with fluidity. Characters should not mime the action of writing, typing or sending an email. Direct address to the audience is probably the smoothest way to get across long-distance correspondences. During heightened scenes or to emphasize certain moments, these suggestions can be modified or ignored as seen fit. For instant messaging, the characters can speak out the abbreviations and symbols. 2 3 SCENE ONE SETTING: Abilene, Kansas and Kabul, Afghanistan. LORENZO LAFARHOFF, 15, sits in his bedroom writing a letter. MAURICE A. CREELY, a 20-year- old with glasses, eats cookies and reads the letter. LORENZO To Whom It May Concern, at the 1st Marine Division of the United States Armed Forces I read an article in the Abilene Chronicle and wished to contact Sgt. Maurice A. Creely. I found his rescue story very cool.