The Lived Experiences and Embodiment of Asthma and Sports and Exercise in the South Asian Population: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now I Can Dance Free Ebook

FREENOW I CAN DANCE EBOOK Tina Arena | 336 pages | 06 May 2014 | HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd | 9780732297565 | English | Sydney, Australia Tina Arena - Now I Can Dance Lyrics Watch the video for Now I Can Dance from Tina Arena's In Deep for free, and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. Though I can only imagine the sadness In your eyes Please understand Now I can dance All alone the other night I came to realise we'd be friends for life It was always meant to be For some people the heavens can get it so right Like an angel you see You have graciously offered a hand You'd be so proud of me Now I'm finally taking a stand Now I can dance. Do You Love Me (Now That I Can Dance) is the only album issued by The Contours during their recording career at Motown Records. Issued on Motown's Gordy subsidiary in October (see in music), the album includes the hit title track and the number 21 R&B hit single " Shake Sherry ". The Contours - Do You Love Me (Now That I Can dance) Lyrics Now I Can Dance is also the title of Tina Arena's memoir released in October In , Arena updated her autobiography with the release of a new edition of Now I Can Dance, with new content covering her relocation from France back to Australia, being inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame, the release of new music, and new musical ventures. Please understand, now I can dance Though I can only imagine the sadness in your eyes Please understand, now I can dance So I hope this finds you well Sun is shining down eastern valley ways So good, be free Can dance and laugh and just be me So good, be free (Now, now I can dance) The clouds above have disappeared Oh now, now I can dance Now. -

A Black Woman's Journey to the Promised Land

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2011 Purgatory's Place in The South: A Black Woman's Journey to the Promised Land Consuela Jean Ward Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ward, Consuela Jean, "Purgatory's Place in The South: A Black Woman's Journey to the Promised Land" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 552. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/552 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURGATORY‟S PLACE IN THE SOUTH: A BLACK WOMAN‟S JOURNEY TO THE PROMISED LAND by CONSUELA JEAN WARD (Under the Direction of Ming Fang He) ABSTRACT Using critical race theory (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; Ladson-Billings, 2003; Stovall, 2005), Black feminist thought (Collins, 2000), and identity theory of oppression (Hardiman & Jackson, 1997) as the theoretical framework and autobiographical narrative inquiry (He, 2003; Moody,1968; Angleou, 1969; Hurston, 1965; hooks,1996; Jacobs, 1861) as the methodology, I explored the formal and informal educational experiences I received and reciprocated in Black church ideology and white schools and how they shaped my identity and lived experience as a Black woman in the South. I chronicled paradigm shifts in my thinking along my journey from Black Christian fundamentalism and poverty to a socially mobile agnostic college administrator and diversity educator. -

Australian and New Zealand Karaoke Song Book

Australian & NZ Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 1927 Allison Durbin If I Could CKA16-06 Don't Come Any Closer TKC14-03 If I Could TKCK16-02 I Have Loved Me A Man NZ02-02 ABBA I Have Loved Me A Man TKC02-02 Waterloo DU02-16 I Have Loved Me A Man TKC07-11 AC-DC Put Your Hand In The Hand CKA32-11 For Those About To Rock TKCK24-01 Put Your Hand In The Hand TKCK32-11 For Those About To Rock We Salute You CKA24-14 Amiel It's A Long Way To The Top MRA002-14 Another Stupid Love Song CKA22-02 Long Way To The Top CKA04-01 Another Stupid Love Song TKC22-15 Long Way To The Top TKCK04-08 Another Stupid Love Song TKCK22-15 Thunderstruck CKA18-18 Anastacia Thunderstruck TKCK18-01 I'm Outta Love CKA13-04 TNT CKA21-03 I'm Outta Love TKCK13-01 TNT TKCK21-01 One Day In Your Life MRA005-15 Whole Lotta Rosie CKA25-10 Androids, The Whole Lotta Rosie TKCK25-01 Do It With Madonna CKA20-12 You Shook Me All Night Long CKA01-11 Do It With Madonna TKCK20-02 You Shook Me All Night Long DU01-15 Angels, The You Shook Me All Night Long TKCK01-10 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again CKA01-03 Adam Brand Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again TKCK01-08 Dirt Track Cowboy CKA28-17 Dogs Are Talking CKA30-17 Dirt Track Cowboy TKCK28-01 Dogs Are Talking TKCK30-01 Get Loud CKA29-17 No Secrets CKA33-02 Get Loud TKCK29-01 Take A Long Line CKA05-01 Good Friends CKA28-09 Take A Long Line TKCK05-02 Good Friends TKCK28-02 Angus & Julia Stone Grandpa's Piano CKA19-14 Big Jet Plane CKA33-05 Grandpa's Piano TKCK19-07 Anika Moa Last Man Standing CKA14-13 -

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK of YOU 1927

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK OF YOU 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 1927 IF I COULD 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 3OH3 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH3, KESHA BLAH BLAH BLAH 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEY EVERYBODY 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT JUST A LIL' BIT A HA TAKE ON ME A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA ANGEL EYES ABBA CHIQUITA ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR ABBA HEAD OVER HEELS ABBA HONEY HONEY ABBA LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME ABBA MAMMA MIA ABBA SO LONG ABBA SUPER TROUPER ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC ABBA WATERLOO ABBA WINNER TAKES IT ALL ABBA AS GOOD AS NEW ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DAY BEFORE YOU CAME ABBA FERNANDO ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA I HAVE A DREAM ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY ABBA NAME OF THE GAME ABBA ONE OF US ABBA RING RING ABBA ROCK ME ABBA SOS ABBA SUMMER NIGHT CITY ABBA VOULEZ VOUS ABC LOOK OF LOVE ACDC LONG WAY TO THE TOP ACDC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC JAILBREAK AC-DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE AC-DC ROCK N ROLL TRAIN AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC-DC BACK IN BLACK AC-DC FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK AC-DC HEATSEEKER AC-DC HELL'S BELLS AC-DC HIGHWAY TO HELL AC-DC JACK, THE AC-DC LET THERE BE ROCK AC-DC LONG WAY TO THE TOP AC-DC STIFF UPPER LIP AC-DC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC TNT AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE OF BASE THE SIGN ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ADAM HARVEY BETTER THAN THIS ADAM LAMBERT IF I HAD YOU ADAM LAMBERT TIME FOR MIRACLES ADELE HELLO AEROSMITH -

2017 Songbooks (Autosaved).Xlsx

Song Title Artist Code 1 Mortin Solveig & Same White 21412 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 20606 1999 Prince 20517 #9 dream John Lennon 8417 1 + 1 Beyonce 9298 1 2 3 One Two Three Len Barry 4616 1 2 step Missy Elliot 7538 1 Thing Amerie 20018 1, 2 Step Ciara ft. Missy Elliott 20125 10 Million People Example 10203 100 Years Five For Fighting 4453 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6117 1000 miles away Hoodoo Gurus 7921 1000 stars natalie bathing 8588 12:51 Strokes 4329 15 FEET OF SNOW Johnny Diesel 9015 17 Forever metro station 8699 18 and life skid row 7664 18 Till i die Bryan Adams 8065 1959 Lee Kernagan 9145 1973 James Blunt 8159 1983 Neon Trees 9216 2 Become 1 Jewel 4454 2 FACED LOUISE 8973 2 hearts Kylie Minogue 8206 20 good reasons thirsty merc 9696 21 Guns Greenday 8643 21 questions 50 Cent 9407 21st century breakdown Greenday 8718 21st century girl willow smith 9204 22 Taylor Swift 9933 22 (twenty-two) Lily Allen 8700 22 steps damien leith 8161 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 21533 3 (one two three) Britney Spears 8668 3 am Matchbox 20 3861 3 words cheryl cole f. will 8747 4 ever Veronicas 7494 4 Minutes Madonna & JT 8284 4,003,221 Tears From Now Judy Stone 20347 45 Shinedown 4330 48 Special Suzi Quattro 9756 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 21195 5, 6, 7, 8. steps 8789 50 50 Lemar 20381 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 1805 50 ways to say Goodbye Train 9873 500 miles Proclaimers 7209 6 WORDS WRETCH 32 21068 7 11 BEYONCE 21041 7 Days Craig David 2704 7 things Miley Cyrus 8467 8675309 Jenny Tommy Tutone 1807 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 20210 99 Red Balloons Nena -

Magic Pudding Music Credits

Music Composed by Chris Harriott Original Songs Composed by Chris Harriott and Dennis Watkins (Cast as indicated in track listing below) Music Producer Chris Harriott Music Consultant Christine Woodruff Orchestrated and Conducted by Christopher Gordon Additional Orchestrations Larry Muhoberac Nerida Tyson-Chew Music Preparation Peter Mapleson Laura Bishop Jessica Wells Rob Workman Orchestral Contractor Coralie Hartl Concert Master Phillip Hartl Recorded at Studios 301, Sydney Recording Engineer Richard Lush Assistant Engineer Nicholas Cervonaro Additional Musicians Drums Hamish Stuart Guitars Peter Watson Keyboards Rob Workman Keyboards/Programming Chris Harriott Harmonica Peter Edwards Additional Recording Sunstone Music, Sydney Backing Vocals Arranger Tony Backhouse Music Mixed at Trackdown Digital Recording Engineer Simon Leadley Music Editor Tim Ryan Additional Music Editor Damian Candusso Music Mix Engineer Kathy Naunton SONGS "It's A Wonderful Day" Written by Chris Harriott and Dennis Watkins Performed by Geoffrey Rush Published by Energee Licensing "My Heart Beats" Written by Chris Harriott and Dennis Watkins Performed by Toni Collette Published by Energee Licensing "Albert, The Magic Pudding" Written by Chris Harriott and Dennis Watkins Performed by John Cleese, Sam Neill, Geoffrey Rush, Hugo Weaving, Dave Gibson, Greg Carroll & Chorus Published by Energee Licensing "The Puddin' Owner's Song" Written by Chris Harriott and Dennis Watkins Performed by Hugo Weaving, Sam Neill, Geoffrey Rush Published by Energee Licensing "It's Worse -

Now I Can Dance Free

FREE NOW I CAN DANCE PDF Tina Arena | 336 pages | 06 May 2014 | HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd | 9780732297565 | English | Sydney, Australia Now I Can Dance by Tina Arena It was the third single taken from Arena's third studio album In Deep It was written by Arena while living in L. InArena updated her autobiography with the release of a new edition of Now I Can Dance, Now I Can Dance new content covering her relocation from France back to Australia, being inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame, the release of new music, and new musical ventures. Tina Arena born Filippina Lydia Arena; 1 November is an Australian singer, songwriter, musical theatre actress, talent show judge and record producer. She has sold over eight million records worldwide to date. Tina has accepted the position of judge on the reboot of Young Talent Time in Australia. The original series made her a household name. We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly. Forgot your password? Retrieve it. Get promoted. Powered by OnRad. Think you know music? Test your MusicIQ here! In Lyrics. By Artist. By Album. Tina Arena Tina Arena born Filippina Lydia Arena; 1 Now I Can Dance is an Australian singer, songwriter, musical theatre actress, talent show judge and record Now I Can Dance. Genre: Electronic. Notify me of new comments via email. -

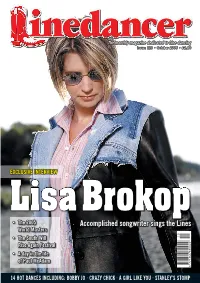

Accomplished Songwriter Sings the Lines

ThemonthlymagazinededicatedtoLinedancingThe monthly magazine dedicated to Line dancing Issue:113•October2005•£2.80Issue: 113 • October 2005 • £2.80 EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW Lisa Brokop • The 2005 Accomplished songwriter sings the Lines World Masters • The South Will 10 Rise Again Festival • AdayinthelifeA day in the life of Paul McAdam 9 771366 650024 14 HOT DANCES INCLUDING: BOBBY JO · CRAZY CHICK · A GIRL LIKE YOU · STANLEY’S STOMP 92860 OCTOBER 2005 Editorial and Advertising Clare House Dear Dancers 166 Lord Street Southport, PR9 0QA It’s a changing world and we have to move with the times. Tel: 01704 392300 Fax: 01704 501678 As our readers know, this magazine is produced by a handful Subscription Enquiries of dedicated people. We all love working on the magazine and Tel: 01704 392339 thoroughly enjoy putting it together from all the information [email protected] you send each month. It’s a joy to be a part of that process and speaking personally, I am lucky to be able to combine my Agent Enquiries career and my hobby in a way that allows me to deliver a top Michael Hegarty • Tel: 0161 281 6441 quality magazine for Line dancers. [email protected] Publisher Linedancer has been the centre of our world for nine years and Betty Drummond no doubt it will always remain so. However, it is a changing [email protected] world and the Internet has made a major change to the way The Linedancer Team we bring you information. As publishers, we must be just as committed to the standard of your website as we are to the Acting Editor standard of your magazine. -

Cataloguemusical

PARTENAIRE Date: 01 / 11 / 2000 CATALOGUE MUSICAL SERVEUR VOCAL 01 49 82 70 71 DONNEZ DU RYTHME A VOTRE IMAGE ! ATOUT SON www.atoutson.fr 3 rue de la Grande Ceinture Tél : 01 49 82 70 00 94370 Sucy-en-Brie Fax : 01 49 82 70 60 Serveur vocal: 01 49 82 70 71 E-Mail : [email protected] Sarl au capital de 20.000 Euros - RCS CRETEIL B 405 105 115 - SIRET 405 105 115 000 19 SOMMAIRE 2 Serveur Mode dEmploi 3 Le Catalogue 3 Musique Classique 7 Variétés Françaises 13 Variétés Internationales 24 Musiques Instrumentales 27 Le Jazz 30 Le Blues 31 Musiques du Monde 33 Musiques Régionales 34 Musiques de Films 36 Musiques Série TV 37 Musiques de Pub 38 Musiques de Noël 39 Les Années 60 39 Les Années 70 40 Les Années 80 40 Les Années 90 41 Plays-Backs 43 Musiques Libres de Droits 44 Bruitages 45 Communication Sonore 46 Les Droits SACEM & SCPP 47 Formulaire Page 1 SERVEUR MODE D'EMPLOI Qui sommes nous ? Catalogue musical Top ten Nos réalisations Journal téléphoné Sommaire Nous contacter 01 49 82 70 71 * 24 h / 24 h 7 j / 7 j AVEC VOTRE EQUIPE& CHOISISSEZ LA MUSIQUE QUI VOUS RESSEMBLE ! * Communication sans surtaxe Page 2 M u s i q u e C l a s s i q u e Code T i t r e s Code T i t r e s ADAM BERG CONCERTO POUR VIOLON ET ORCHESTRE A LA MÉMOIRE D UN ANGE 1999 GISELLE 1065 ANDANTE 1001 SI J ÉTAIS ROI BERIO ADOLFO ALBENIZ 1066 MARIA ISABELLA VALSE 1002 SUITE ESPAGNOLE 1067 PRIMAVERA MAZURKA ALBINONI BERIO LUCIANO 1003 ADAGIO EN SOL MINEUR 1068 WASSER KLAVIER 1004 CONCERTO POUR CORDES ET CLAVECIN EN RE MAJEUR OP7 N1 BERLIOZ 1005 SONATE EN MI MINEUR OP5 N9 -

Untitled 10980 Simple Plan P

NEW SONG Song Title No. Popularized By Composer/Lyricist YOUNG ADAM R, ALLIGATOR SKY 12685 OWL CITY CHRYSTOPHER SHAWN BUMUHOS MAN ANG ULAN (GREEN ROSE OST) 2595 JERICHO ROSALES Jericho Rosales ANDREW HARR, JERMAINE JACKSON, CALIFORNIA KING BED 12675 RIHANNA PRISCILLA RENEA HAMILTON Jason Derulo, Chaz DON'T WANNA GO HOME 12698 JASON DERULO William, David Delazyn SCHULTZ MICHAEL ABRAM,JACKSON CURTIS DOWN ON ME 12699 JEREMIH FT. 50 CENT. JAMES,JAMES KEITH ERIC,FELTON JEREMY P Guy Berryman, Jonny Buckland, Will Champion, Chris Martin, EVERY TEARDROP IS A WATERFALL 12689 COLDPLAY Peter Allen, Adrienne Anderson GAWING LANGIT ANG MUNDO 2592 SIAKOL Noel Palomo Armando C. Perez, Shaffer GIVE ME EVERYTHING 12703 PITBULL (FT. NE-YO, AFROJACK, NAYER) Smith, Nick van de Wall SCOGGIN JAMES HOUSTON, GOLDMARK ANDREW, GOD GAVE ME YOU 12681 BRYAN WHITE HICKS JAMES DEAN Stefani Germanotta, HAIR 12702 LADY GAGA Nadir Khayat HEY DAYDREAMER 2593 SOMEDAY DREAM Deedee MAX MARTIN, JOHAN I WANNA GO 12692 BRITNEY SPEARS KARL SCHUSTER BOURDON ROBERT, DELSON BRAD, FARRELL DAVID MICHAEL, SHINODA MIKE, IRIDESCENT 12686 LINKIN PARK HAHN JOSEPH, BENNINGTON CHESTER ITULOY MO LANG 2591 SIAKOL Noel Palomo Stefani Germanotta, JUDAS 12679 LADY GAGA Nadir Khayat Charles Kelley, Hillary Scott, JUST A KISS 12700 LADY ANTEBELLUM Dave Haywood, Dallas Davidson WILLIAM ADAMS,TOMMY BROWN,STEPHEN SHADOWEN, STACY FERGUSON,JOSHUA ALVAREZ,RODNEY JERKINS, JUST CAN'T GET ENOUGH 12695 BLACK EYED PEAS JAIME GOMEZ,JULIE FROST,ALLAN PINEDA,JABBAR STEVENS LUKASZ GOTTWALD, BONNIE MCKEE, LAST FRIDAY NIGHT TGIF 12687 KATY PERRY KATY PERRY, MAX MARTIN M.Mathers, R.Montgomery, LIGHTERS 12701 BAD MEETS EVIL FT. -

Go Square Dance Summer!

01. MERICAN UAR E DAN C "The International Magazine of Sqvant No matter how you do it, GO SQUARE DANCE SUMMER! $3.50 July 2001 Register FREE! The Original & Largest Internet Square Dance Directory! Clubs, Associations, Callers 8 Cuers Listings, Articles, History, Resources, Vendors...and much more! Western Square Dancing - DOSADO.COM 2 squate Demme. DIISADH coot I he pretio Internet Patel to Wanton swam liabosalt Weiner 1 NAM I= we., to tar Lei Dm Fa seer Role Nee Bore Seep Rabe* Howe Search images Motor Mel Prof Ed, Adaaa1 o e)Cro Lae, " Western Square Dancing The Premier Internet Portal to DOSADO COM'" Western Square Dancingl Hems club, Antral Sellliete Celle II_C12/11111 Saltwate Refsut cle FREE! Submit New Uselnq feedback Casualty Sisal) Ustilii/y AssF. Tuesday May 71. 7000 Three New Features! Check Your Links! Beet Recruiting Ideas! De you NOM a fink en Search DOSADO.COM There are a "bazmon- way. to record new DOSADO.001117 If yes, dancers Many of you have been quite please check n for errors so successful so wed like In mete you to share that all links take OSOOM to your successful recruiting expenences four coned' addtessl We Western Submit your ideas via Onlij (plain feet believe we two removed all Square Dancing please • no attachments) and well select nonfunctioning links appropnate articles lo publish Well Man Please let us know d you Quid( Find Site Index! these articles nght here on the front page and then continue find a non-functioning or Items on an inside page with other articles on this crdical subject. -

At the Star Gold Coast During August

Media Release 2 August 2017 WHAT’S ON AT THE STAR GOLD COAST IN AUGUST Always entertaining, The Star Gold Coast will host a packed calendar of thrilling dining and entertainment experiences with special events, progressive dinners, concerts from internationally acclaimed artists, and decadent menus this August. SPECIAL EVENTS The Star Grazing Food Tour From Thursday August 10 Starting on Thursday August 10, The Star Gold Coast is inviting you on an exclusive and intimate culinary journey around the property showcasing a depth of flavours at a selection of its award- winning signature restaurants. Under the guise of The Star Grazing Food Tour, you will be able to experience the delights of four contrasting venues in the one night, with dishes expertly paired with wines, and a lovely host to guide you through the evening. Beginning at cutting-edge Japanese restaurant Kiyomi with a glass of Moët & Chandon in hand, you’ll enjoy some of internationally renowned chef Chase Kojima’s modern yet authentic Japanese fare including the famed crispy rice, spicy tuna. Proud owner of one chef hat, your time at Kiyomi will set the scene for what’s to come. Next on the menu is Mei Wei Dumplings where you will be transported to the hawker style lanes of Hong Kong with a selection of crowd favourite dumplings. With a menu driven by Mandarin and Cantonese flavours, watch the chefs in action through the 2.6m viewing panel where they expertly hand-craft fresh mouth-watering creations onsite daily and you’ll see first-hand why the translation of Mei Wei to delicious could not be more accurate Inspired by the roof-top restaurants along the Amalfi Coast, Cucina Vivo will draw on traditional Italian food culture for your main course, celebrating good company, great food and beautiful surrounds.