Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Music as Representational Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vv9t9pz Author Walker, Daniel Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Daniel Walker 2014 © Copyright by Daniel Walker 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening by Daniel Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes to this dissertation; the first is a monograph, and the second is a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I Music is a language that can be used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions. It has been part of the human experience since before recorded history, and has established a unique place in our consciousness, and in our hearts by expressing that which words alone cannot express. ii My individual interest in the musical language is its use in telling stories, and in particular in the form of composition referred to as program music; music that tells a story on its own without the aid of images, dance or text. The topic of this dissertation follows this line of interest with specific focus on the compositional techniques and creative approach that divide program music across a representational spectrum from literal to abstract. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano

COLOMBIAN NATIONALISM: FOUR MUSICAL PERSPECTIVES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Ana Maria Trujillo A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music The University of Memphis December 2011 ABSTRACT Trujillo, Ana Maria. DMA. The University of Memphis. December/2011. Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano. Dr. Kenneth Kreitner, Ph.D. This paper explores the Colombian nationalistic musical movement, which was born as a search for identity that various composers undertook in order to discover the roots of Colombian musical folklore. These roots, while distinct, have all played a significant part in the formation of the culture that gave birth to a unified national identity. It is this identity that acts as a recurring motif throughout the works of the four composers mentioned in this study, each representing a different stage of the nationalistic movement according to their respective generations, backgrounds, and ideological postures. The idea of universalism and the integration of a national identity into the sphere of the Western musical tradition is a dilemma that has caused internal struggle and strife among generations of musicians and artists in general. This paper strives to open a new path in the research of nationalistic music for violin and piano through the analyses of four works written for this type of chamber ensemble: the third movement of the Sonata Op. 7 No.1 for Violin and Piano by Guillermo Uribe Holguín; Lopeziana, piece for Violin and Piano by Adolfo Mejía; Sonata for Violin and Piano No.3 by Luís Antonio Escobar; and Dúo rapsódico con aires de currulao for Violin and Piano by Andrés Posada. -

Chopin and Poland Cory Mckay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1

Chopin and Poland Cory McKay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1 The nineteenth century was a time when he had a Polish mother and was raised in people were looking for something new and Poland, his father was French. Finally, there exciting in the arts. The Romantics valued is no doubt that Chopin was trained exten- the exotic and many artists, writers and sively in the conventional musical styles of composers created works that conjured im- western Europe while growing up in Poland. ages of distant places, in terms of both time It is thus understandable that at first glance and location. Nationalist movements were some would see the Polish influence on rising up all over Europe, leading to an em- Chopin's music as trivial. Indeed, there cer- phasis on distinctive cultural styles in music tainly are compositions of his which show rather than an international homogeneity. very little Polish influence. However, upon Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin used this op- further investigation, it becomes clear that portunity to go beyond the conventions of the music that he heard in Poland while his time and introduce music that had the growing up did indeed have a persistent and unique character of his native Poland to the pervasive influence on a large proportion of ears of western Europe. Chopin wrote music his music. with a distinctly Polish flare that was influ- The Polish influence is most obviously ential in the Polish nationalist movement. seen in Chopin's polonaises and mazurkas, Before proceeding to discuss the politi- both of which are traditional Polish dance cal aspect of Chopin's work, it is first neces- forms. -

Activity Sheet

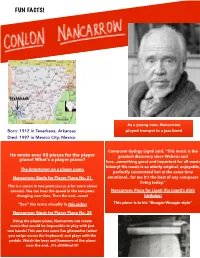

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

The Latin Tinge

The Latin Tinge 1800-1900 Concerning John Storm Roberts s The Latin Tinge: The lmpact of Latin Music in the United Statcs. see the booA: notice at page 139ofthis issue. Thefollowing essay is n:pandl'dfrom a puper read at the 1976 an· nual meeting of the American Musi<·ological Society. in Waslti11gto11. D.C. Translated into Spunish with the title "Visión musical norteamericana de las otras Américas hacia 1900... this article apfH!ared in Revista Musical Chilena XXXII 137 ( 1977). 5-35. Dr. Luis Merino. editor. A:ind/y permi11ed publica/ion in English. D URING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, American interest in Latin American political events stimulated a constant stream of sheet music publications. The two decades during which Latin America was most to the fore were of course the 1840's and the 1890's. However, as early as 1810 the New York-based Peter Weldon' published there a Brazilian Waltz for flute, clarinet, or violin and piano, welcoming King John VI of Portugal to the New World. In an article tracing musical relations between Brazil and the United States, Carleton Sprague Smith began with Weldon's waltz, the Portuguese title of which was Favorita Waltz Brazi/e11se Para Piano Forte com Accompanhamento de Flauta Clarinete o Violin. 2 The engraving on Weldon's cover shows the royal disembarkation at Rio de Janeiro in January of 1808. According to Smith, a change from major to minor would infuse more Brazilian character into the perky waltz theme. Weldon's piano part glistens with brilliant sixteenth-note arpeggiated figuration in the treble supported by a close-position waltz bass. -

Audio Playlist Scroll to See Program

Guest Artist Recital: 2006-10-29 -- Deanna Swoboda, tuba and Marcelina Turcanu, piano Audio Playlist Access to audio and video playlists restricted to current faculty, staff, and students. If you have questions, please contact the Rita Benton Music Library at [email protected]. Scroll to see Program PDF \ - f SCHOOL!1fMUSlC ' 1906-2006 g uesJREC)llAL \, SUNDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2006, 2:00 p.m. HARPER HALL Deanna Swoboda, tuba Marcelina Turcanu, piano L. uJ~! DIVISION OF PERFORMING ARTS oF lowA COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS & SCIENCES guestRECITAL Deanna Swoboda, tuba OCTOBER 29, 2006, 2 p.m. HARPER HALL Marcelina Turcanu, piano PROGRAM Sonata No. 2 in E-flat Johann Sebastian BACH Allegro Moderato (1685-1750) Siciliano transcribed and edited by Floyd Cooley Allegro Estrellita ("My Little Star") Manuel PONCE (1882- 1948) arr. Rich Ridenour and Patrick Sheridan Concerto for Bass Tuba Ralph Vaughan WILLIAMS Allegro moderato (1872- 1958) Romanza · Rondo Alla Tadesca Relentless Grooves: Cuba Sam PILAFIAN Bolero (b. 1949) Mambo Fnugg Oystein BAADSVIK (b. 1966) Csardas Vittorio MONTI (1868- 1922) BIOGRAPHY DEANNA SWOBODA teaches tuba and euphonium at Western Michigan University and performs with the Western Brass Quintet. She previously taught at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and Las Vegas Arts Academy as well as at the University of Northern Iowa, University of Denver, University of Idaho, National Conservatory of Madrid (Spain), and Deutschen Tubaforum-Hammelberg (Germany). In 2000, she joined the Dallas Brass, a six-piece ensemble that travels the United States and Europe presenting approximately 100 concerts per year working extensively in the public schools and at colleges and universities. -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father.