Rule by Punch Cards Or: How Computers Are a Menace to Liberty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herman Hollerith and Early Mechanical/Electrical Tabulator/Sorters

Herman Hollerith and early mechanical/electrical tabulator/sorters The US Constitution requires that the people of the U.S. be counted every ten years and that the members of the House of Representatives “be apportioned among the States according to their respective numbers”1. (The other house of Congress, the Senate, has two members from each state.) Accordingly, every ten years, a census is taken. By 1880, the census was becoming harder and harder to accomplish. Everything was done on paper. Marks were placed in squares on paper, the marked squares were counted, and of course people made many mistakes. Further, the census was used more and more not just to count people but to get useful data on age, gender, marital status, working status, and so on. There were more and more marks to make and count! Herman Hollerith: the inventor of mechanical/electrical data processing systems Herman Hollerith graduated from the Columbia University School of Mines (in New York City) in 1879 at the age of 19. He knew about the problems with the census and be- gan research into mechanizing part of the counting of the census. In 1882, he taught me- chanical engineering at MIT and conducted his first experiments with punched cards. He was extremely successful, and he soon moved to Washington D.C. and set up a company, The Hollerith Electric Tabulating System. By the middle of the 1880’s, his first punched-card system was working. His company provided the Census Office with the equipment used in processing the 1890 census —62 million punched cards were processed by his machines, cutting two years off the time to complete the census. -

Herman Hollerith and the Evolution of Electronic Accounting Machines (EAM)

Herman Hollerith and the Evolution of Electronic Accounting Machines Thomas J. Bergin ©Computer History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Instant Quiz What is technology? Identify five examples of different technologies. How does technology arise, i.e., what is the process of invention? Identify three early tools. Identify the technique used to make these tools. 7/9/2012 2 Random House/Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, Second Edition (1998) Technology, n, is the branch of knowledge that deals with the creation and use of technical means and their interrelation with life, society, and the environment drawing upon such subjects as industrial arts, engineering, applied science and pure science technical, adj., belonging or pertaining to an art, science, or the like technique, n, the body of specialized procedures and methods used in any specific field, esp. in an area of applied science. 7/9/2012 3 Homo farber (man the tool-maker) Homo, n, the genus of bipedal primates that includes modern humans and several extinct forms, distinguished by their large brains and a dependence upon tools. Christian Jurgensen Thompsen (c 1816) in dividing artifacts for a Museum, identified the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages The Stone age was later divided into Greek-derived technical terms Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Mesolithic (old, new, middle) 7/9/2012 4 We are surrounded by technology Technology is embodied in the tools and techniques/processes that solve problems or empower people to do things. saw: enables us to cut wood hammer: enables us to build homes automobile: enables us to move about cities: enable us to have shelter and safety stove: allows us to cook indoors telephone: allows us to communicate 7/9/2012 5 Philosophical Questions: Which came first the chicken or the egg? Does technology result from man’s needs? (“pull” theory) or Do people invent things that enable man to improve his lifestyle? (“push” theory) In truth, both processes are operative at all times and in all ages. -

![Papers of Herman Hollerith [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7374/papers-of-herman-hollerith-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-2157374.webp)

Papers of Herman Hollerith [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Herman Hollerith A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by James Byers and Wilhelmena Curry Revised and expanded by T. Michael Womack Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 1997 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms997007 Latest revision: 2005-02-16 Collection Summary Title: Papers of Herman Hollerith Span Dates: 1850-1982 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1910-1927) ID No.: MSS49510 Creator: Hollerith, Herman, 1860-1929 Extent: 11,700 items; 34 containers plus 1 oversize; 13.6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Correspondence, diary, financial and business papers, patents by Herman Hollerith and others, blueprints, drawings, a Hollerith machine punch plate, writings about Hollerith by Geoffrey Austrian and others, biographical material, and other papers relating to Hollerith tabulating machines and their use in census taking (1890-1910), operation of Tabulating Machine Company and its merger with two other companies forming Computer-Tabulating-Recording Company (1911), and Hollerith's association with this company and its successor, International Business Machines Corporation. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Names: Hollerith, Herman, 1860-1929 Hayes, C. L. (Clarke L.)--Correspondence Hollerith, Herman, b. 1892--Correspondence Merrill, Philip P.--Correspondence Metcalf, Samuel G.--Correspondence Talcott, Charles G. -

Herman H. Hollerith

Herman H. Hollerith Born February 20, 1860, Buffalo, N. Y; died November 17, 1929, Washington, D. C.; inventor of the punched card which bears his name and the associated machinery for use in the 1890 US census; founder of the company (Hollerith Tabulating Company) that eventually became IBM. Education: graduate, School of Mines, Columbia University, 1879; PhD, Columbia University, 1890. Professional Experience: statistician, US Bureau of the Census, 1879-1882; instructor, MIT, 1882-1883; US Patent Office, 1883-1886; self-employed, 1886-1929. Herman Hollerith was born in 1860 in Buffalo, N.Y, and graduated at the age of 19 from the Columbia School of Mines. His supervisor, William P. Trowbridge, who was a consultant to the US Bureau of the Census, introduced Hollerith to John Shaw Billings, who employed him as an assistant in his work on the statistical analysis of the 1880 census. Billings remarked that there ought to some way to mechanize the tabulating process. Following this early involvement with the bureau, Hollerith moved to MIT1 in 1882 with Francis Walker, who had served as the director of the bureau, and where Hollerith developed a flair for invention. A year later he returned to Washington to become an examiner for the Patent Office. During this period at MIT he developed the basic ideas of the tabulating machine, using rolls of perforated paper tape as the means of input. Replacing the continuous tape by cards, Hollerith also developed a pantograph punch for preparing the data on the cards, and a “reader” in which spring loaded pins completed electrical circuits to increment selected counters in the tabulator. -

The Triumph and Tragedy of IBM's Business with the Third Reich

Dealing with The Devil: The Triumph and Tragedy of IBM’s Business with the Third Reich Harry Murphy Junior Division Paper Length: 2500 Innovation and invention drive the world forward and thrive off a free market that rewards individuals and companies that can tap into supply and demand. During tragedy, especially wartime, this can take a dark turn when the triumph of invention and profit is gained from human tragedy. International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) saw warfare as an opportunity to capitalize off of both sides. As the Nazis rose to power, they needed the machinery to identify, organize, and number the Jewish population. IBM sought this as a favorable position for corporate gain and began leasing tabulating machinery to the Nazi regime. IBM’s endorsement of the Third Reich yielded capital gain at the cost of millions of lives. This advanced technology, which enabled IBM’s profit from the Holocaust, set the scene for the company’s dominance throughout the 20th-century while ultimately enabling a calculated genocide. Background In January 1933, Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor of Germany.1 Hitler implemented many racial laws that prohibited Jews from public living. Jewish businesses were plundered, and many were driven from their jobs and homes.2 Jewish companies were consumed by the German government and ran by German officials. As Hitler’s regime progressed, he looked to institutionalize a core virtue of Nazism into German society: the identification, ostracization, and extermination of the Jewish community. In his attempt to expunge Jews from Germany, in 1935, 1 Enderis, Guido. “Group Formed by Papen.” The New York Times, January 31, 1933. -

Early History of Computers: Machines for Mass Calculation

Early History of Computers: Machines for Mass Calculation Waseda University, SILS, Science, Technology and Society (LE202) The control revolution • We often think of computers as increasing individual freedoms and liberties. The first computers, however, were associated with the needs of administrators to calculate and control. • The massive technological systems of the modern world led to a crisis of control and the electronic computer was used as a way of handling this situation. • The early drive for computing was largely funded and motivated by military, statebuilding and corporate needs. • The early images of computers in popular culture and science fiction are always of large machines associated with power and control. (There were no personal computers in science fiction novels or movies before the 1970s.) Before electronic computers • There were counting boards of various kinds in most ancient and medieval cultures (abacus, soroban, etc.). • In the early modern period, Pascal, Leibniz and others developed analog calculators. • The most advanced analog (mechanical) calculators were designed by Charles Babbage (1791–1871), but never built. • In the early 20th century, a “computer” meant a person Babbage’s Difference Engine (usually a woman) who carried out calculations. Punch cards • The rise of mass production and mass distribution around the turn of the 20th cenury gave rise to a crisis of control. • This lead to new techniques of data processing and bureaucratic management. • There were a number of different types of machines that were used to deal with this crisis but the most common was the punch card machine. • These consisted of analog computers and electric tabulators that could process around 10,000 punch cards a month. -

Herman Hollerith (1860-1929)

HERMAN HOLLERITH (1860-1929) Biography: His parents were immigrants to the United States from Germany in 1848. An engineering graduate of the Columbia School of Mines in 1879 as a mining engineer, with low marks only in bookkeeping and machines. He liked good cigars, fine wine, Guernsey cows, and money. He founded his own business and merged with others. Stayed with the CTR company until 1921, but participated in its activities less and less.... He avoided general manager Watson as much as possible, and devoted most of his time to the life of a gentleman farmer on Chesapeake Bay. He seemed to be more interested in boating, farming, and raising Guernsey cattle than in running a business. Retired in 1921 Died of a heart attack in 1929. Professional life: After a study he was employed as statistician at the US Census Bureau. In 1882 he joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he taught mechanical engineering and began his experiments with a punched paper tape. In 1884 he obtained a post in the U.S. Patent Office in Washington and experience in this work probably helped him to receive more than 30 US patents. He invented among others an electrically actuated brake system (considered him as his highest achievement) for trains but it lost out to the Westinghouse steam-actuated brake. He patented a method to convert the information on punched cards into electrical impulses and punches devices named the Hollerith Electric Tabulating System, passed for manufacture to „Pratt and Whitney” and „Western Electric Company”. Hollerith's system was first tested on tabulating mortality statistics in Baltimore, New Jersey in 1887 and was in use in the 1890 US census. -

Co-Evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction Between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries Jo A

Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction Between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries Jo Anne Yates WP#3575-93 Revised October 1993 Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries JoAnne Yates Sloan School of Management MIT E52-545 50 Memorial Drive Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-7157 [email protected] Sloan School Working Paper #3575-93 Center for Coordination Science Working Paper #145 October 1993 Accepted for publication in Business History Review ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to Martin Campbell-Kelly, Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Glenn Porter, Philip Scranton, Eric von Hippel and two anonymous reviewers of the Business History Review for comments on earlier versions of this paper. I appreciate the able assistance of Daniel May and the library staff at the Metropolitan Life Archives, and of Michael Nash, Margery McNinch, and the staff of the Hagley Museum and Library. This research has been generously supported by the Center for Coordination Science, by the MIT Sloan School of Management, and by the Hagley Museum and Library. Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries In 1890, at the invitation of inventor Herman Hollerith, 25 members of the Actuarial Society of America attended a demonstration of a new type of information-handling equipment: the punched-card tabulator. According to a news account of the meeting, the life insurance actuaries attended because "Any labor-saving device that can be used in the preparation of tabular statements is of interest to actuaries." l Their interest was justified by the magnitude of the information- handling tasks faced by their life insurance firms. -

Punched-Card Sorters and Rapid Selectors: Information Management Between the Wars Jay L

101 Punched-Card Sorters and Rapid Selectors: Information Management between the Wars Jay L. Gordon Youngstown State University The contemporary nexus of technology, information management, and social practice has been characterized by James Beniger as the product of a “Control Revolution” that unfolded during the century leading up to World War I. What we now commonly call the “information society,” Beniger argues, has evolved out of this “complex of rapid changes in the technologi- cal and economic arrangements by which information is collected, stored, processed, and communicated, and through which formal or programmed decisions might effect societal control” (vi). 1 Through the ongoing dialectic between technological innovations and bureaucratic institutions, each contributing to the propagation and development of the other, the Control Revolution continues, in Beniger’s view, “unabated” to this day. Beniger’s Control Revolution involves mainly large-scale economic and sociocultural shifts, but we have also witnessed astonishing changes in how individuals can use technology (provided they have the resources) to generate, shape, and communicate information for ourselves. We produce and store our professional work and our private lives on personal comput- ers. We send and receive virtually all forms of information by way of digital data transmissions. Many of us own microcomputers every bit as powerful as we once imagined they might become, displacing or obviating any need for a whole array of technological and professional services. Computers serve as desktop publishing houses, personal secretaries, and private ac- countants; customizable radio receivers and television transmitters; win- dows on thousands of instantly accessible library card catalogues; drafting tables that can help even the clumsiest draw perfect Bezier curves. -

Tabulating Machines III

Chapter Tabulating Machines III In the latter half of the nineteenth century, as the American popula tion continued to grow and ever more detailed population statistics were demanded, the standard manual techniques of tabulating and analyzing the ten-yearly U.S. National Census returns became more and more inadequate. The earliest mechanical assistance was pro vided by the Seaton machine which was introduced for the 1870 Census and used extensively during the 1880 Census [1]. This was a simple device, consisting of a set of rollers on which Census tabulation forms could be mounted, which assisted the Census clerks by bringing corresponding sections of several forms into convenient physical jux taposition. ADr. JOHN SHAW BIlliNGS was in charge of the planning of the work on the vital statistics for the 1880 Census. Also involved in this Census, but in a much more junior capacity, was HERMAN HOLLERITH who in 1879 at the age of 19 had been appointed an assistant to Professor WIlliAM TROWBRIDGE of Columbia University, a Chief Special Agent in the Census Office. Several differing accounts have been written of the relative roles of BIlliNGS and HOLLERITH in the invention of a punched card tabulating system. It is generally agreed that in 1880 BIlliNGS encouraged HOLLER ITH to investigate the development of a mechanised tabulation system, but, for example, some accounts have BIlliNGS making the specific suggestion that the system be based on the Jacquard card principle [2]; others have HOLLERITH getting the idea of representing logical and numerical data by holes punched in cards after seeing a conductor punching a railway ticket so as to indicate the physical appearance of the ticket holder [3). -

Word Recognition, Speaker Identification and Advanced Audio Response

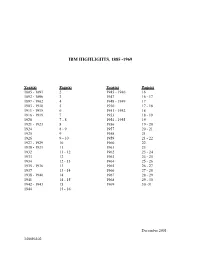

IBM HIGHLIGHTS, 1885 -1969 Year(s) Page(s) Year(s) Page(s) 1885 - 1891 2 1945 - 1946 16 1892 - 1896 3 1947 16 - 17 1897 - 1902 4 1948 - 1949 17 1903 - 1910 5 1950 17 - 18 1911 - 1915 6 1951 - 1952 18 1916 - 1919 7 1953 18 - 19 1920 7 - 8 1954 - 1955 19 1921 - 1923 8 1956 19 - 20 1924 8 - 9 1957 20 - 21 1925 9 1958 21 1926 9 - 10 1959 21 - 22 1927 - 1929 10 1960 22 1930 - 1931 11 1961 23 1932 11 - 12 1962 23 - 24 1933 12 1963 24 - 25 1934 12 - 13 1964 25 - 26 1935 - 1936 13 1965 26 - 27 1937 13 - 14 1966 27 - 28 1938 - 1940 14 1967 28 - 29 1941 14 - 15 1968 29 - 30 1942 - 1943 15 1969 30 -31 1944 15 - 16 December 2001 1406HA02 2 1885 Science & Technology Julius E. Pitrap of Gallipolis, Ohio, patents his first computing scale. (Pitrap’s patents are later acquired by a forerunner of IBM.) 1886 Science & Technology Dr. Herman Hollerith conducts the first practical test of his tabulating system in recording and tabulating vital statistics for the Baltimore (Md.) Department of Health. (Hollerith will later form one of IBM’s predecessor companies.) 1888 Science & Technology Dr. Alexander Dey invents the first dial recorder. (Dey’s business will be acquired by one of IBM’s predecessors in 1907.) 1889 Organization Harlow Bundy incorporates the Bundy Manufacturing Company as the first time recording company in the world. It produces a time clock invented by his brother Willard L., a jeweler in Auburn, N.Y. -

Research Notes on Herman Hollerith 2353

Geoffrey D. Austrian research notes on Herman Hollerith 2353 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Geoffrey D. Austrian research notes on Herman Hollerith 2353 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................