The Intersections of Social Activism, Collective Identity, and Artistic Expression in Documentary Filmmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

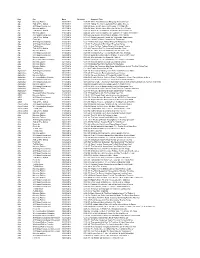

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012 This report covers NPR's reporting on events and trends related to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians during the second quarter of 2012. The report begins with an assessment of the 37 stories and interviews, covered by this review, that aired from April through June on radio shows produced by NPR. The 37 radio items is just one more than the lowest number for any quarter (in July-September 2008) during the past ten years. Over that period, NPR programs have carried an average of nearly 100 items per quarter related to Israel, the Palestinians, or both. I also reviewed 20 news stories, blogs and other items carried exclusively on NPR's website. All of the radio and website-only items covered by this review are shown on the "Israel-Palestinian coverage" page of the website. The opinions expressed in this report are mine alone. Accuracy I carefully reviewed all items for factual accuracy, with special attention to the radio stories, interviews and website postings produced by NPR staffers. NPR's coverage of the region continues to be remarkably accurate for a news organization with very tight deadlines. NPR has posted no corrections on its website for stories that originated during the April-June quarter; two corrections were posted in April concerning items dealt with in my report for the January-March quarter. I found no outright inaccuracies during the period, but I will point out two instances of misleading use of language. Freelance correspondent Sheera Frenkel reported for All Things Considered on May 8 about the status of a hunger strike among Palestinian prisoners. -

The Politics of Homophobia in Brazil: Congress and Social (Counter)Mobilization

The Politics of Homophobia in Brazil: Congress and Social (counter)Mobilization by Robert Tyler Valiquette A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Robert Tyler Valiquette, June, 2017 ABSTRACT THE POLITICS OF HOMOPHOBIA IN BRAZIL: CONGRESS AND SOCAIL (COUNTER)MOBILIZATION Tyler Valiquette Advisor: University of Guelph, 2017 Professor J Díez In recent years, Latin America has seen significant progress in the expansion of LGBT rights such as the implementation of same-sex marriage and the creation of some of the world’s most advanced gender identity laws. Brazil was at the front of this progression and by the early 2000’s, scholars believed Brazil was poised to emerge as Latin America’s gay rights champion. Despite some advancements, the image of Brazil as a gay rights champion is nebulous. The Brazilian Congress has failed in passing federal legislation protecting sexual minorities from violence and discrimination and this thesis seeks to answer why. Qualitative interviews were conducted with LGBT activists, political aides, politicians and Evangelical Pastors. Ultimately this thesis argues that Brazil does not have LGBT anti- discrimination policy because of two factors: 1) a weakening LGBT social movement and 2) a strong countermovement to LGBT rights. iii Acknowledgements Thanks is offered to numerous people upon the completion of this thesis. First, my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Jordi Díez. I first contacted Dr. Díez in 2015 with a simple idea for research. From that moment on, Dr. Díez offered limitless support. -

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

Ten Years of GWOT, the Failure of Democratization, and the Fallacy of "Ungoverned Spaces"

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 5 Number 1 Volume 5, No. 1: Spring 2012 Article 5 Ten Years of GWOT, the Failure of Democratization and the Fallacy of “Ungoverned Spaces” David P. Oakley Kansas State University, [email protected] Patrick Proctor Kansas State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the Portfolio and Security Analysis Commons pp. 1-14 Recommended Citation Oakley, David P. and Proctor, Patrick. "Ten Years of GWOT, the Failure of Democratization and the Fallacy of “Ungoverned Spaces”." Journal of Strategic Security 5, no. 1 (2012) : 1-14. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.5.1.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol5/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ten Years of GWOT, the Failure of Democratization and the Fallacy of “Ungoverned Spaces” Abstract October 7, 2011, marked a decade since the United States invaded Afghanistan and initiated the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT). While most ten-year anniversary gifts involve aluminum, tin, or diamonds, the greatest gift U.S. policymakers can present American citizens is a reconsideration of the logic that guides America's counterterrorism strategy. Although the United States has successfully averted large-scale domestic terrorist attacks, its inability to grasp the nature of the enemy has cost it dearly in wasted resources and, more importantly, lost lives. -

True Colors Resource Guide

bois M gender-neutral M t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois gender-neutral M gender-neutralLOVEM gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch Birls polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme Asexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois M gender-neutral gender-neutral M t t F F ALLY Lesbian INTERSEX butch INTERSEXALLY Birls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual Asexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois LOVE gender-neutral M gender-neutral t F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois bois M gender-neutral M gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident -

The Voices of NPR

Episode 11 – Michael Goldfarb – All Along the Watchtower The Voices of NPR And now a personal word, Michael Goldfarb has the voice of a journalist who has witnessed important events. He speaks with weariness and authority. His voice evokes a chorus of NPR announcers who report from near and distant places. Writer Dierdre Mask noted in an article in the Atlantic magazine, “We can’t see NPR reporters, so we have to picture them. And because they are with us in our most private moments—alone in the car, half-asleep in bed—we start to think we know them.” And we do think we know them. Their voices are iconic: distinct, informative, comforting, familiar. Their voices are the sounds of our better selves when we are bright and learned and engaged in the affairs of the world. No matter the day’s events, they give us hope that in a crazy world, sense and sensibility will prevail. Here are a few names I grew up with: Susan Stamberg, Bob Edwards, Carl Kasell, Noah Adams, Linda Wertheimer, Robert Siegel, Scott Simon, Cokie Roberts, and Bob Mondello. Each name evokes a voice, a style, a beat, that is the news soundtrack of our lives and shared imagination. We hear their stories as they report from bureaus from foreign capitals: Eleanor Beardsley, Paris; Rob Gifford, London; Ofiebea Quist-Arcton, Dakar; and, of course, Sylvia Poggioli, Rome. We hear war correspondents in the thick of battle: Michael Golfarb in Northern Ireland and Bosnia; Kelly McEvers in the midst of death and kidnapping in the Arab Spring, Tom Bowman among the fire and mortars of Helmand Province, and David Gilkey ambushed and killed by the Taliban. -

NPR's 'Political Junkie' Coming to Central New York

NPR’s ‘Political Junkie’ Coming to Central New York Ken Rudin, NPR’s long-time political editor best the same name, Ken Rudin will help set the scene known for his astonishing ability to recall arcane for the 2012 election season. facts regarding all things political will be WRVO’s Rudin and a team of NPR reporters won the Alfred I. guest for a public appearance at Syracuse Stage duPont-Columbia University Silver Baton award for Thursday, May 31st. Grant Reeher, Professor in excellence in broadcast journalism for coverage of the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, campaign finance in 2002. Ken has analyzed Director of the Campbell Public Affairs every congressional race nationally since 1984. Institute and host of WRVO’s Campbell Conversations will join him on-stage as From 1983 through 1991, Ken was deputy host and will pose questions submitted political director and later off-air Capitol Hill in advance by WRVO listeners. Tickets reporter covering the House for ABC News. are available online at WRVO.org. He first joined NPR in 1991 and is reported to have more than 70,000 campaign buttons Known as ‘The Political Junkie’ for his and other political items he has been collecting appearances on the Wednesday edition for more than 50 years. of Talk of the Nation with Neal Conan, and for the NPR blog that he writes of NPR’s Ken Rudin When we announced back in January our first ever WRVO Discovery WRVO to Cruise Cruise with NPR “Eminence in Residence” Carl Kasell aboard as with Carl Kasell our host, we had no idea how popular it would become with WRVO listeners. -

A Structural Analysis of Personal Experience Narratives, the Federal Writers‘ Project to Storycorps

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL EXPERIENCE NARRATIVES, THE FEDERAL WRITERS‘ PROJECT TO STORYCORPS by Megan M. Dickson B.A. May 2007, Utah State University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 16, 2010 Thesis directed by John Michael Vlach Professor of American Studies and of Anthropology © Copyright 2010 by Megan Marie Dickson All rights reserved ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the experiences we each have and share every day— in the park, over the phone, and sometimes even to a government employee (circa 1937), or with a loved one in a cozy StoryCorps sound booth in New York City. To my husband— Perry Dickson—without you, your love and strength, your championing and cheerleading this story would never have been possible. To my parents—Mona and Ken Farnsworth, and Robin Dickson—thank you for your unending love, support, encouragement, and belief. To my son Parker, whose story has only just begun, your vigor and verve for life already bring constant adventure and joy beyond measure. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge and thank the faculty and staff of the American Studies department at The George Washington University. A special thanks to Maureen Kentoff—the most fabulous muse in American Studies Executive Assistant history for helping to navigate the sometime frightful waters of university protocol, and sharing ways to succeed as a non-traditional student; John Michael Vlach—my faithful advisor; Melanie McAlister—Director of Graduate Studies who administered my comprehensive examination; Phyllis Palmer—a woman whose enthusiasm and intellectual spark lit up an otherwise apathetic paper proposal; and Thomas Guglielmo, Chad Heap, Terry Murphy, and Elizabeth Anker—for their teaching prowess and academic acumen. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • noVemBer 2008 Rolling On the River with Burt Wolf Each week, WUSF TV/DT viewers join Burt Wolf, the genial host of Burt Wolf: Travels & Traditions, on his journeys around the world. Wolf has traveled by plane, train and automobile — but a river cruise is his favorite way to see Europe. This month, on November 12, during a two-hour special, Wolf takes us through the heart of Europe on three voyages along the winding Danube River. In Cruising the Danube, Wolf kicks off his leisurely journey in Budapest and then stops off at the fairy tale castles and hidden streets of Burt Wolf’s two- Bratislava, Dürnstein, Melk, Grein, Linz hour river cruise and Passau before coming full circle to Budapest. On his second expedition, special airs Christmas in Vienna, Wolf sets shore November 12 in Vienna, Austria, exploring ancient Christmas traditions (some edible!) at 8 p.m. and festivities at locations ranging WUSF TV/DT from the magnificent Habsburg castle to Vienna’s celebrated outdoor Channel 16 Christmas markets. On the last leg of the voyage, Austrian Monasteries, Wolf takes us inside the abbeys at Melk and Klosterneuburg — each a fascinating realm of history, tradition and treasure. Wolf concludes his journey with lunch at the restaurant of one of Europe’s most talented chefs. Intrigued? If you’re more than an armchair traveler, you can join Burt Wolf in July 2009 on a Danube River cruise with other WUSF friends. Find more information about this once-in-a-lifetime voyage inside! wusf: FIRST choice WUSF Public WUSF TV/DT Broadcasting: November Highlights A range of media choices WORLDFOCUS brings American audiences a deeper understanding WUSF 89.7 of the stories shaping the world provides NPR news and today. -

LGBTQ+ MOVEMENTS & ACTIVISMS WST 6935, Section 17F1, Class Number

LGBTQ+ MOVEMENTS & ACTIVISMS WST 6935, Section 17F1, Class Number: 21172 Mondays, Periods 6-8 (12:50-3:50pm) Ustler 108 Kendal L. Broad, Ph.D. Office Hours: Office: USTLER 301 Tuesdays, 11:30am-2:30pm Phone: (352) 273-0389 and by appointment Email: [email protected] NOTE: Unavailable 9/11 & 10/2 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- COURSE DESCRIPTION There are many ways to study and critically understand lesbian, gay, bisexual, same gender loving, transsexual, transgender, intersex, two-spirit, queerPOC, ally, pansexual, asexual, queer, gender- nonconforming (and more) social justice praxis and activist work. This course will center on considerations (including critiques) of LGBTQ+ social movement strategies. In that regard, it is a course designed to answer the question of how LGBTQ+ social movement work is done (and, to some degree, undone). While there is a range of literatures taking up this question, this seminar is anchored especially in sociological LGBTQ+ social movement research, LGBTQ+ social movement history, and interdisciplinary LGBTQ+ and Sexuality Studies. One aim of the course is to consider recent research engaging core concepts arising from Queer Studies, Queer of Color critique, Intersex studies, Transgender studies and more. A related goal is to engage empirical research while being mindful of critiques of empiricism, especially in relation to LGBTQ+ lives and activisms. As well the course is designed with a certain wariness of embedded patterns erasure and epistemic violence attached to academic incorporation of activist work and so is structured to attend to concepts relevant to LGBTQ + activists and attentive to activist voices and materials. The syllabus for this course should not be read as a comprehensive overview of a field, for there is a good deal of important material left out.