PROGRAM NOTES Manuel De Falla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Amor Brujo

Luis Fernando Pérez piano Basque National Orchestra Carlo Rizzi direction MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946) Noches en los jardines de España - Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne 1 - En el Generalife (Au Generalife) 2 - Danza lejana (Danse lointaine) 3 - En los jardines de la Sierra de Córdoba (Dans les jardins de la Sierra de Cordoue) El sombrero de tres picos - Trois danses du Tricorne 4 - Danza de los vecinos (Danse des voisins) 5 - Danza de la molinera (Danse de la meunière) 6 - Danza del molinero (Danse du meunier) 7 - Fantasía Bética - Fantaisie bétique El amor brujo (piano suite) - L´Amour sorcier (piano suite) 8 - Pantomima (Pantomine) 9 - Danza del fuego fatuo (Chanson du feu follet) 10 - Danza del terror (Danse de la terreur) 11 - El Círculo magico (Le cercle magique) 12 - Danza ritual del fuego (Danse du feu) Enregistrement réalisé les 11 et 12 avril 2013 à l’Auditorium de Bordeaux (plages 1 à 3) et du 15 au 17 juin 2013 à la Aula de Música de Alcalá de Henares (plages 4 à 12) / Direction artistique, prise de son et montage : Jiri Heger (plages 1 à 3) et José Miguel Martínez (plages 4 à 12) / Piano : Steinway D (plages 1 à 3) et Yamaha (plages 4 à 12) Accordeur : Gérard Fauvin (plages 1 à 3) et Leonardo Pizzollante (plages 4 à 12) / Conception et suivi artistique : René Martin, François-René Martin et Christian Meyrignac / Photos : Marine de Lafregeyre / Design : Jean-Michel Bouchet - LM Portfolio / Réalisation digipack : saga.illico / Fabriqué par Sony DADC Austria. / & © 2014 MIRARE, MIR 219 www.mirare.fr TRACKS 2 PLAGES CD MANUEL DE FALLA Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne manière traditionnelle du concerto classico-romantique pour piano et orchestre. -

Delightful Listening Experiences in Quasi-Chamber Music. the D

delightful listening experiences in and 1925. He was an exacting artist quasi-chamber music. The D Major who set such high standards for Concerto for harpsichord, originally himself that instead of serving as a scored for two violins, viola, bass, challenge to him, they became an two oboes and two horns, was writ inhibitive force which prevented ten around 1784. The last move his creative impulse from being ful ment, in a gypsy style rondo, is filled. jovial Haydn at his merriest. Although most of Falla's music presents the sonic picture of Spain Concerto for Harpsichord, Flute, we have come to expect from Span Oboe, Clarinet, Violin and Cello ish music, with its typical rhythms Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) and melodic flourishes, the present During most of the eighteenth and Concerto is somewhat exceptional nineteenth centuries, when com in this respect. Here the Spanish posers of note were emerging from idiom is refined and stylized, which most of the major countries of Eu lifts the piece above the level of be rope, ilittle of musical importance ing outwardly and picturesquely was heard from Spain. Not until the Spanish. The solo harpsichord part, turn of the century did Spanish mu although totally interwoven with the sic reassert itself on the world scene, other instruments, clearly evokes primarily through the music of Man the keyboard style of Domenico uel de Falla, who became the lead Scarlatti, the Italian composer who ing figure of the modern Spanish spent the major part of his career school of composition. in Spain some two hundred years before. -

Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russi

‘I wish for my life’s roses to have fewer thorns’: Heinrich Neuhaus and Alternative Narratives of Selfhood in Soviet Russia Abstract Heinrich Neuhaus (1888—1964) was the Soviet era’s most iconic musicians. Settling in Russia reluctantly he was dismayed by the policies of the Soviet State and unable to engage with contemporary narratives of selfhood in the wake of the Revolution. In creating a new aesthetic territory that defined himself as Russian rather than Soviet Neuhaus embodied an ambiguous territory whereby his views both resonated with and challenged aspects of Soviet- era culture. This article traces how Neuhaus adopted the idea of self-reflective or ‘autobiographical’ art through an interdisciplinary melding of ideas from Boris Pasternak, Alexander Blok and Mikhail Vrubel. In exposing the resulting tension between his understanding of Russian and Soviet selfhood, it nuances our understanding of the cultural identities within this era. Finally, discussing this tension in relation to Neuhaus’s contextualisation of the artistic persona of Dmitri Shostakovich, it contributes to a long- needed reappraisal of his relationship with the composer. I would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of the Guildhall School that enabled me to make a trip to archives in Moscow to undertake research for this article. Dr Maria Razumovskaya Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London Word count: 15,109 Key words: identity, selfhood, Russia, Heinrich Neuhaus, Soviet, poetry Contact email: [email protected] Short biographical statement: Maria Razumovskaya completed her doctoral thesis (Heinrich Neuhaus: Aesthetics and Philosophy of an Interpretation, 2015) as an AHRC doctoral scholar at the Royal College of Music in London. -

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 the Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 The Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr. Richard Benjamin THE GRAMMY® FOUNDATION eonard Bernstein is cele brated as an artist, a CENTER FOP LEAR ll I IJ G teacher, and a scholar. His Lbook Findings expresses the joy he found in lifelong learning, and expounds his belief that the use of the arts in all aspects of education would instill that same joy in others. The Young People's Concerts were but one example of his teaching and scholarship. One of those concerts was devoted to celebrating teachers and the teaching profession. He said: "Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world - the most unselfish, difficult, and hon orable profession. But it is also the most unappreciated, underrat Los Angeles. Devoted to improv There was an entrepreneurial ed, underpaid, and under-praised ing schools through the use of dimension from the start, with profession in the world." the arts, and driven by teacher each school using a few core leadership, the Center seeks to principles and local teachers Just before his death, Bernstein build the capacity in teachers and designing and customizing their established the Leonard Bernstein students to be a combination of local applications. That spirit Center for Learning Through the artist, teacher, and scholar. remains today. School teams went Arts, then in Nashville Tennessee. The early days in Nashville, their own way, collaborating That Center, and its incarnations were, from an educator's point of internally as well as with their along the way, has led to what is view, a splendid blend of rigorous own communities, to create better now a major educational reform research and talented expertise, schools using the "best practices" model, located within the with a solid reliance on teacher from within and from elsewhere. -

Compact Disc C36 2018 5-20.Pdf (386.2Kb)

~'N\t>~' ~Q... "Jf\71 SCHOOL OF MUSIC C3G \iJ\J UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON oz6\8 5-cXD CAMPUS PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRAS side-by-side with BELLEVUE YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA conducted by Gabriela Garza Canales " Lorenzo Guggenheim Mario Alejandro Torres and Teresa Metzger Howe th Sunday, May 20 , 2018 3:00pm, Meany Theater UW MUSIC '3 2017-18 SEASON CPO & BYSO CONDUCTORS student at the University of Washington under the mentorship of Dr. David Rahbee and Ludovic Morlot. Gabriela Garza Canales (born July 1 st, 1989, Lorenzo is a Teaching Assistant in UW where he is co Monterrey, Nuevo Leon) is a Mexican conductor and conductor of the Campus Phil harmonia Orchestras percussionist. She is currently in her first year of and Assistant conductor of UWSO. He graduated doctoral studies at the University of Washington with Honors in Orchestral Conducting from the under the mentorship of David Alexander Rahbee Catholic University of Argentina in 2014. He also and Ludovic Morlot. She is also co-conductor of the studied Contemporary Music Ensemble Conducting Campus Philharmonia Orchestras and assistant in the music conservatory "Manuel de Falla" in conductor of the UW Symphony Orchestra. Buenos Aires. Gabriela holds a Master of Music in Orchestral He has been an active part of the musical Conducting from the University of New Mexico, scene of the Universisty of Washington presenting under the mentorship of Dr. Jorge Perez-Gomez. concerts with CPO and UW Chamber Orchestra with She also holds a Bachelor Degree in Music Luke Fitzpatrick as soloist. He also collaborated with Performance, with emphasis in percussion from the the Modern Music Ensamble making the US Premiere University of New Mexico, under the direct instruction of Delgado's Cotores Congetados and presenting's of Professor Scott Ney. -

Falla Y Stravinsky: Una Amistad Hispano-Rusa

38 etc Domingo, 14 de enero de 2007 La Opinión de Granada CONCIERTOFALLA Falla y Stravinsky: una Vida Breve Radio El néctar y la pana amistad hispano-rusa en ‘Música de nadie’ b ‘Música de nadie’ es el sugeren- z YVAN NOMMICK. Granada te título de un espacio radiofónico Apuntes semanal que dirige Pierre Élie Ma- na estrecha amistad unió a Falla mou los domingos en Radio Clási- y Stravinsky desde que se co- ca (de 22.00 a 23.00 horas). Las Unocieron en París en 1910, año Tres retratos indefinibles propuestas del pro- en el que los Ballets Russes de Dia- La amistad, el afecto grama las ensarta su conductor con ghilev estrenaron ‘El pájaro de fue- y el respeto artístico breves e intensos parlamentos. El go’ en la Ópera de la capital francesa. que existieron entre próximo domingo 21 de enero es- En este breve texto examinaremos Falla y Stravinsky se cucharemos ‘Cuando el límite imi- algunos momentos significativos de evidencian en los ta el límite’, con lieder de Schu- las relaciones entre los dos músicos. tres retratos que se mann sobre los que se recitan poe- Falla fue testigo privilegiado de las intercambiaron, mas japoneses o el experimento primeras representaciones de ‘La con- cuyas dedicatorias, del pianista Kikuchi sobre la ‘Tos- sagración de la primavera’ en 1913, en redactadas en fran- ca’ de Puccini. el Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, y de cés, son muy llamati- su reposición en 1914. Dos años des- vas. Así, el 18 de pués, describió en La Tribuna de Ma- marzo de 1929, Falla drid cómo los músicos “de mala fe y mandó al compositor Publicación -

Janina Fialkowska Piano

Série Dorothy Morton pour artistes invités Dorothy Morton Invited Guests Series Janina Fialkowska piano eenn collaborationcollaboration avecavec • inin collaborationcollaboration withwith 3344e SSérieérie CBC/McGillCBC/McGill • 3344tthh CCBC/McGillBC/McGill SeriesSeries ccbcmusic.ca/mcgillbcmusic.ca/mcgill Le lundi 25 février 2013 Monday, February 25, 2013 à 19 h 30, salle Pollack 7:30 pm, Pollack Hall COONCERTNCERT Six pièces lyriques / Six Lyric Pieces EDVARD GRIEG Arietta, Op. 12, No. 1 (1843-1907) Sommerfugl (Butterfl y), Op. 43, No. 1 Notturno, Op. 54, No. 4 Bekken (Brooklet), Op. 62, No. 4 Trolltog (March of the Dwarfs), Op. 54, No. 3 Efterklang (Remembrances), Op. 71, No. 7 4 Impromptus, D 935, Op. Posth. 142 FRANZ SCHUBERT en fa mineur / in F minor (1797-1828) en la bémol majeur / in A-fl at major en si bémol majeur / in B-fl at major en fa mineur / in F minor ~ entracte ~ Polonaise en mi bémol mineur / in E-fl at minor, Op. 26, No. 2 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Scherzo no 4 en mi majeur / No. 4 in E major, Op. 54 (1810-1849) Valse en la bémol majeur / Waltz in A-fl at major, Op. 64, No. 3 Mazurka en do majeur / in C major, Op. 56, No. 2 Mazurka en do mineur / in C minor, Op. 56, No. 3 Scherzo no 1 en si mineur / No. 1 in B minor, Op. 20 CCee concertconcert estest enregistréenregistré parpar CBCCBC MusicMusic enen vidéovidéo pourpour diffusiondiffusion enen ligneligne (à(à cbcmusic.ca/mcgill)cbcmusic.ca/mcgill) etet enen audioaudio ppourour ddiffusioniffusion dansdans lele cadrecadre dede l'émissionl'émission IInn CConcertoncert aaniméenimée parpar PPaoloaolo PietropaoloPietropaolo lesles dimanchesdimanches à 1111 h 0000 ssurur lleses ondesondes dede CBCCBC RadioRadio 2 (93,5(93,5 FMFM à Montréal).Montréal). -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Bergenpac.Org UPCOMING SHOWS on the TAUB STAGE at BERGENPAC

2019-2020 bergenpac.org UPCOMING SHOWS ON THE TAUB STAGE AT BERGENPAC DECEMBER (CONT.) 2019 The Very Hungry Caterpillar featuring Dream Snow & Other 15 1pm & 4pm OCTOBER Eric Carle Favorites presented by PSE&G 3 8:00pm Vince Neil of Mötley Crüe presented by WDHA 17 7:00pm Lior Suchard: The Israeli Illusionist – ON SALE SOON! 4 8:00pm Steven Wright presented by Johl & Company 20 8:00pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 5 8:00pm Michael Martocci presents Sinatra Meets The Sopranos 21 1pm & 4:30pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 6 1:00pm Jeff Boyer’s Big Bubble Bonanza 22 1:00pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 10 8:00pm Rick Wakeman: Grumpy Old Man Tour 11 8:00pm Explosion de la Salsa de Ayer 2020 JANUARY 13 7:30pm Gin Blossoms: The New Miserable Experience Satisfaction: The International Rolling Stones Tribute Show: 15 7:30pm So You Think You Can Dance Live! 2019 4 8:00pm Paint It Black 16 8:00pm TOTO: 40 Trips Around the Sun; Benzel-Busch Concert Series New Jersey Symphony Orchestra presents Winter Festival: My Fellow Supporters of the Arts, 9 7:30pm 19 8:00pm The Jim Breuer Residency: Comedy, Stories & More Vol. III Mozart’s Don Giovanni Sergio Mendes & Bebel Gilberto: The 60th Anniversary 11 8:00pm The Capitol Steps: The Lyin’ Kings I am excited to share Bergen Performing Art Center’s 2019-20 lineup 20 7:30pm of Bossa Nova with you today. Boasting a variety of headliners, up-and-comers and 12 3:00pm Neil Berg’s 104 Years of Broadway Mystery Science Theater 3000 Live: The Great Cheesy everything in between across the genres, we expect everyone will find 24 8:00pm 17 8:00pm The Simon & Garfunkel Story: A Tribute to Simon & Garfunkel something they love. -

Leopold Stokowski, "Latin" Music, and Pan Americanism

Leopold Stokowski, "Latin" Music, and Pan Americanism Carol A. Hess C oNDUCTOR LEOPOLD Stokowski ( 1882-1977), "the rum and coca-cola school of Latin American whose career bridged the circumspect world of clas composers," neatly conflating the 1944 Andrews Sis sical music with HolJywood glitz. encounterecl in ters song with "serious" Latin American composition. 2 varying clegrecs both of these realms in an often Such elasticity fit Stokowski to a tcc. On thc one overlooked aspcct of his career: promoting the music hand, with his genius for bringing the classics to of Latín American and Spanish composers, primaril y the mass public, Stokowski was used to serving up those of the twentieth century. In the U.S .. Stokow ''light classics," as can be scen in hi s movies, which ski's adopted country. this repertory was often con include Wah Disney's Famasia of 1940 and One veniently labeled '·Latín." due as much to lack of Htmdred Men anda Girl of 1937. On the other hand. subtlety on thc part of marketcrs as thc less-than the superbly trained artist in Stokowski was both an nuanccd perspective of the public. which has often experimentcr and a promoter of new music. A self resisted dífferentiatíng the Spanish-speaking coun described "egocentric"-he later declared. " I always tries.1 In acldition to concert repertory, "Latin'' music want to he first"-Stokowski was always on the might include Spanish-language popular songs, lookout for novelty.3 This might in volve transcribing English-language songs on Spanish or Latín Ameri Bach for an orchestra undreamt of in the eighteenth can topics, or practically any work that incorporated century or premiering works as varied as Pierrot claves, güiro, or Phrygian melodic turns. -

Listening Program Script I

Non-Directed Music Listening Program Series I Non-Directed Music Listening Program Script Series I Week 1 Composer: Manuel de Falla (1876 – 1946) Composition: “Ritual Fire Dance” from “El Amor Brujo” Performance: Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy Recording: “Greatest Hits of The Ballet, Vol. 1” CBS XMT 45658 Day 1: This week’s listening selection is titled “Ritual Fire Dance”. It was composed by Manuel de Falla. Manuel de Falla was a Spanish musician who used ideas from folk stories and folk music in his compositions. The “Ritual Fire Dance” is from a ballet called “Bewitched By Love” and describes in musical images how the heroine tries to chase away an evil spirit which has been bothering her. Day 2: This week’s feature selection is “Ritual Fire Dance” composed by the Spanish writer Manuel de Falla. In this piece of music, de Falla has used the effects of repetition, gradual crescendo, and ostinato rhythms to create this very exciting composition. Crescendo is a musical term which means the music gets gradually louder. Listen to the “Ritual Fire Dance” this time to see how the effect of the ‘crescendo’ helps give a feeling of excitement to the piece. Day 3: This week’s featured selection, “Ritual Fire Dance”, was written by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla in 1915. Yesterday we mentioned how the composer made use of the effect of gradually getting louder to help create excitement. Do you remember the musical term for the effect of gradually increasing the volume? If you were thinking of the word ‘crescendo’ you are correct. -

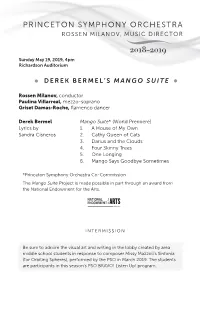

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse.