Comparative Studies 2009.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECFG-Latvia-2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: A Latvian musician plays a popular folk instrument - the dūdas (bagpipe), photo courtesy of Culture Grams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Baltic States. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Latvia Latvian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A US jumpmaster inspects a Latvian paratrooper during International Jump Week hosted by Special Operations Command Europe). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

El Lissitzky, Made a Career of Utilizing Art for Social and Political Change

"The space must be a kind of showcase, a stage, on which the pictures make their appearance as actors in a drama (or comedy). It should not imitate a living space." SYNOPSIS Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky, made a career of utilizing art for social and political change. Although often highly abstract and theoretical, Lissitzky's work was able speak to the prevailing political discourse of his native Russia, and then the nascent Soviet Union. Following Kazimir Malevich in the Suprematist idiom, Lissitzky used color and basic shapes to make strong political statements. Lissitzky also challenged conventions concerning art, and his Proun series of two-dimensional Suprematist paintings sought to combine architecture and three-dimensional space with traditional, albeit abstract, two- dimensional imagery. A teacher for much of his career and ever an innovator, Lissitzky's work spanned the media of graphic design, © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org typography, photography, photomontage, book design, and architectural design. The work of this cerebral artist was a force of change, deeply influencing movements and related figures such as De Stijl and the Bauhaus. KEY IDEAS Lissitzky believed that art and life could mesh and that the former could deeply affect the latter. He identified the graphic arts, particularly posters and books, and architecture as effective conduits for reaching the public. Consequently, his designs, whether for graphic productions or buildings, were often unfiltered political messages. Despite being comprised of rudimentary shapes and colors, a poster by Lissitzky could make a strong statement for political change and a building could evoke ideas of communality and egalitarianism. -

Short CV For: Alexander Lubotzky

Short CV for: Alexander Lubotzky Personal: • born 28/6/56 in Israel. • Married to Yardenna Lubotzky (+ six children) Studies: • B. Sc., Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 1975. • Ph.D., Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 1979. (Supervisor: H. Fussten- berg, Thesis: Profinite groups and the congruence subgroup problem.) Employment: • 1982 - current: Institute of Mathematics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Professor - Holding the Maurice and Clara Weil Chair in Mathematics • 1999-current: Adjunct Professor at Yale University • Academic Year 2005-2006: Leading a year long research program at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton on \Lie Groups, Repre- sentations and Discrete Mathematics." Previous Employment: • Bar-Ilan University, 1976-1982 • Israeli Defense Forces, 1977-1982 • Member of the Israeli Parliament (Knesset), 1996-1999 Visiting Positions: • Yale University (several times for semesters or years) • Stanford University (84/5) • University of Chicago (92/3) • Columbia University (Elenberg visiting Professor Fall 2000) 1 • Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (2005/6) Main prizes and Academic Honors: • Elected as Foreign Honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences • Ferran Sunyer i Balaguer Prize twice: 1993 for the book: \Discrete Groups, Expanding Groups and Invariant Measures", Prog. in math 125, Birkhauser 1994, and in 2002 joint with Professor Dan Segal from Oxford for the book \Subgroup Growth", Prog. in Math. 212, Birkhauser 2003. • The Rothschild Prize 2002. • The Erdos Prize in 1991. Editorial work: • Israel Journal of Mathematics (1990-now) • Journal of Algebra (1990-2005) • GAFA (1990-2000) • European Journal of Combinatorics • Geometric Dedicata • Journal of the Glasgow Mathematical Scientists Books and papers: • Author of 3 books and over 90 papers. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

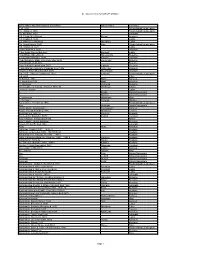

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Contributions to the Knowledge of Latvian Coleoptera. 8

80 Contributions to the Knowledge of Latvian Coleoptera. 8 Contributions to the Knowledge of Latvian Coleoptera. 8. 1 DMITRY TELNOV , ANDRIS BUKEJS , JĀNIS GAILIS , MĀRTI ŅŠ KALNI ŅŠ, ALEXANDER NAPOLOV , UĢIS PITER ĀNS , KRISTAPS VILKS 1 – Corresponding author: Stopi ņu novads, D ārza iela 10, LV-2130, Dzidri ņas, Latvia; e-mail: [email protected] TELNOV D., BUKEJS A., GAILIS J., KALNI ŅŠ M., NAPOLOV A., PITER ĀNS U., VILKS K., 2010. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF LATVIAN COLEOPTERA. 8. - Latvijas Entomologs , 48: 80-91. Abstract: This paper contains information on 10 new and 144 little known and protected beetle species in Latvia, collected between 1939 and 2009. Key words: Coleoptera, fauna, Latvia, little-known species. Introduction List of Species Current publication is a result of studies Carabidae on Latvian Coleoptera made by Latvian Carabus clathratus clathratus LINNAEUS , 1761 coleopterists in 1939-2009. The aim of the Latgale: Dvietes paliene (flood-lands) PNT, current publication is to improve our knowledge Putnu sala, 22.04.2009 (3) flood-lands of River on fauna and ecology of beetles in the Baltic Dviete, leg. M.Kalni ņš. region, with special accent made on poorly known, rare or protected species. Carabus coriaceus coriaceus LINNAEUS , 1758 Ten new and 144 little known or protected Kurzeme: Dundaga parish, Sl ītere NP, Kolka, species of Coleoptera collected are recorded for 03.07.2009 (1) dry coastal pine forest, observed Latvia. New faunal information on 11 by K.Vilks. particularly protected Coleopteran species is given. Particular species are new to the whole * Dolichus halensis (SCHALLER , 1783) Fennoscandian region or / and Baltic States (i.e. -

Path Dependency and Landscape Biographies in Latgale, Latvia: a Comparative Analysis

Europ. Countrys. · 3· 2010 · p. 151-168 DOI: 10.2478/v10091-010-0011-7 European Countryside MENDELU PATH DEPENDENCY AND LANDSCAPE BIOGRAPHIES IN LATGALE, LATVIA: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Anita Zarina1 Received 30 September 2010; Accepted 15 October 2010 Abstract: This paper focuses on the path dependency of landscapes in Latgale, Latvia from the present perspective at the regional and local scale. During the last centuries Latvia’s landscapes have passed through radical changes, which were driven by political events. Each new political era discarded the ideas of the previous era and subsequently reorganized the land(scape) according to the new views. At the regional level the role of history is significant in analyzing landscapes while at the local level the main force is people, often themselves not knowing the history of the place but putting the existing path dependency into practise or disregarding it. The biographies of two former villages are discussed: one which is nearly deserted but filled with forgotten or neglected cultural heritage values and the other – alive and interwoven with some old (almost forgotten) cultural practises. Path dependency in landscapes is relevant only regarding the attachment of people to a place and the experience on which their further desires are based. Key words: Landscape biographies, landscape change, Latgale, path dependency Rezumējums: Raksta pamatā ir pēctecīguma (path dependence) izpausmes Latgales ainavā reģionālā un lokālā mērogā no šodienas skatupunkta. Pēdējo gadsimtu laikā Latvijā ir notikušas dramatiskas ainavas pārmaiņas, to galvenie rosinātāji – politisko varu maiņas. Katra jaunā politiskā ēra veidoja jaunas ainavas saskaņā ar tās ideoloģiju un idejām. Rakstā tiek diskutēts, ka reģionāla mēroga ainavas studijas ir cieši saistītas ar vēstures izpratni un tās lomu, kamēr lokālā mērogā galvenie ainavas veidotāji ir cilvēki un to darbības, kuri bieži vien pat neapzinās vietas/reģiona vēsturi, bet praktizē vai ignorē daudzas paražas vai telpiskās struktūras pēctecības ainavā. -

A Group Theoretic Characterization of Linear Groups

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNAL OF ALGEBRA 113, 207-214 (1988) A Group Theoretic Characterization of Linear Groups ALEXANDER LUBOTZKY Institute qf Mathematics, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 91904 Communicated by Jacques Tits Received May 12, 1986 Let r be a group. When is f linear? This is an old problem. The first to study this question systematically was Malcev in 1940 [M], who essen- tially reduced the problem to finitely generated groups. (Note that a finitely generated group is linear over some field of characteristic zero if and only if it can be embedded in CL,(C) for some n.) Very little progress was made since that paper of Malcev, although, as linear groups are a quite special type of group, many necessary conditions were obtained, e.g., r should be residually finite and even virtually residually-p for almost all primes p, f should be virtually torsion free, and if not solvable by finite it has a free non-abelian subgroup, etc. (cf. [Z]). Of course, none of these properties characterizes the finitely generated linear groups over @. In this paper we give such a characterization using the congruence structure of r. First some definitions: For a group H, d(H) denotes the minimal number of generators for H. DEFINITION. Let p be a prime and c an integer. A p-congruence structure (with a bound c) for a group r is a descending chain of finite index normal subgroups of r = N, 2 N, 2 N, z . -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

Counting Arithmetic Lattices and Surfaces

ANNALS OF MATHEMATICS Counting arithmetic lattices and surfaces By Mikhail Belolipetsky, Tsachik Gelander, Alexander Lubotzky, and Aner Shalev SECOND SERIES, VOL. 172, NO. 3 November, 2010 anmaah Annals of Mathematics, 172 (2010), 2197–2221 Counting arithmetic lattices and surfaces By MIKHAIL BELOLIPETSKY, TSACHIK GELANDER, ALEXANDER LUBOTZKY, and ANER SHALEV Abstract We give estimates on the number ALH .x/ of conjugacy classes of arithmetic lattices of covolume at most x in a simple Lie group H . In particular, we obtain a first concrete estimate on the number of arithmetic 3-manifolds of volume at most x. Our main result is for the classical case H PSL.2; R/ where we show D that log AL .x/ 1 lim H : x x log x D 2 !1 The proofs use several different techniques: geometric (bounding the number of generators of as a function of its covolume), number theoretic (bounding the number of maximal such ) and sharp estimates on the character values of the symmetric groups (to bound the subgroup growth of ). 1. Introduction Let H be a noncompact simple Lie group with a fixed Haar measure .A discrete subgroup of H is called a lattice if . H / < . A classical theorem of n 1 Wang[Wan72] asserts that if H is not locally isomorphic to PSL2.R/ or PSL2.C/, then for every 0 < x R the number LH .x/ of conjugacy classes of lattices in H of 2 covolume at most x is finite. This result was greatly extended by Borel and Prasad [BP89]. In recent years there has been an attempt to quantify Wang’s theorem and to give some estimates on LH .x/ (see[BGLM02],[Gel04],[GLNP04],[Bel07] and[BL]). -

Litvak Art in the Context of the Ecole De Paris ANTANAS ANDRIJAUSKAS

Litvak Art in the Context of the Ecole de Paris ANTANAS ANDRIJAUSKAS Introduction Some studies, like this one, begin as fragmentary thoughts recorded on various occasions: they are born naturally and imperceptibly when the time is right. In my childhood, while wandering with a fishing pole outside Veisiejai near Lake Ančia, I slipped, and my feet disturbed a thick layer of moss under which was buried a dark stone with strange characters in an unknown language. My elders later told me that these were vestiges of the Lithuanian Jewish culture that had once existed here. That was my first contact with the culture of Lith- uanian Jews, the Litvaks. I learned that before World War II, in Veisiejai, a small town in Dzūkija, there had been a large Jewish community. The inventor of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, had also lived here. When I moved there with my parents after the war, at the age of six, there were no Litvaks left in this town. The entire community was mercilessly annihilated. Much later, in my travels, I continued to encounter, in various contexts, manifestations of Litvak culture - works in Parisian exhibition halls and galleries with the names of Jew- ish Litvak artists who represented the third generation resid- ing abroad. Next to their names I often saw the words litvak or juif d'origine lituanicnne. It greatly intrigued me that in Paris so many people identified themselves with - and had roots in - ANTANAS ANDRIJAUSKAS is Head of the Department of Compara- tive Cultural Studies at the Institute for Culture, Philosophy, and Art, and President of the Lithuanian Aesthetic Association. -

A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia

religions Article A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia Anita Stasulane Faculty of Humanities, Daugavpils University, Daugavpils LV-5401, Latvia; [email protected] Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: In the early 20th century, Dievtur¯ıba, a reconstructed form of paganism, laid claim to the status of an indigenous religious tradition in Latvia. Having experienced various changes over the course of the century, Dievtur¯ıba has not disappeared from the Latvian cultural space and gained new manifestations with an increase in attempts to strengthen indigenous identity as a result of the pressures of globalization. This article provides a historical analytical overview about the conditions that have determined the reconstruction of the indigenous Latvian religious tradition in the early 20th century, how its form changed in the late 20th century and the types of new features it has acquired nowadays. The beginnings of the Dievturi movement show how dynamic the relationship has been between indigeneity and nationalism: indigenous, cultural and ethnic roots were put forward as the criteria of authenticity for reconstructed paganism, and they fitted in perfectly with nativist discourse, which is based on the conviction that a nation’s ethnic composition must correspond with the state’s titular nation. With the weakening of the Soviet regime, attempts emerged amongst folklore groups to revive ancient Latvian traditions, including religious rituals as well. Distancing itself from the folk tradition preservation movement, Dievtur¯ıba nowadays nonetheless strives to identify itself as a Latvian lifestyle movement and emphasizes that it represents an ethnic religion which is the people’s spiritual foundation and a part of intangible cultural heritage.