Understanding the Ban of Bollywood in Manipur: Objectives, Ramifications and Public Consensus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Jan Page 3

Imphal Times Supplementary issue PagePage No. No. 3 3 Clock ticking, Naga talks stuck for long over CM Visits Samadhi of issue of symbols: Report Maharaja Gambhir Singh Agency had been resolved However, it is politically however, did not confirm Naga National Political Dimapur, Jan 7, between the two sides and “unviable for the Centre the same. Groups (NNPGs), a draft agreement was to accept demands such ”I would not like to comprising As the tenure of the NDA ‘almost ready’ by then. as a separate Naga flag, comment on it as we are representatives of six government at the Centre “But a change in Naga even though, sources engaged with the peace influential Naga political nears completion, there is position has led to said, it has agreed to process,” The Indian groups and the National no progress on apprehensions that any guarantee protection of Express’ report said quoting Socialist Council of negotiations for a peace gains made since 2014 will the Naga identity,” it RN Ravi. Nagalim (Isak-Muivah) or accord with Naga armed be lost with a change in added. Ravi has been closely NSCN-IM, had met groups, with talks stuck political dispensation at “But if these changes associated with interlocutors of the for almost a year due to the Centre,” it added. can be brought later negotiations with Naga Central government last an “intransigent position Quoting sources, the through a democratic groups for decades, first in month, and another taken” by the Naga side report said that logjam political process, the various capacities as an meeting is scheduled in on ‘symbolic’ issues, is largely due to issue Centre would have no Intelligence Bureau officer Delhi this month. -

Political Structure of Manipur

NAGALAND UNIVERSITY (A Central University Estd. By the Act of Parliament No. 35 of 1989) Headquarters - Lumami. P.O. Makokchung - 79860 I Department of Sociology ~j !Jfo . (J)ate . CER TI FICA TE This is certified that I have supervised and gone through the entire pages of the Ph.D. thesis entitled "A Sociological Study of Political Elite in Manipur'' submitted This is further certified that this research work of Oinam Momoton Singh, carried out under my supervision is his original work and has not been submitted for any degree to any other university or institute. Supervisor ~~ (Dr. Kshetri Rajendra Singh) Associate Professor Place : Lumami. Department of Sociology, Nagaland University Date : '1..,/1~2- Hqs: L\unami .ftssociate <Professor [)eptt of $c".IOI09.Y Neg8'and university HQ:Lumaml DECLARATION The Nagaland University October, 2012. I, Mr. Oinam Momoton Singh, hereby declare that the contents of this thesis is the record of my work done and the subject matter of this thesis did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that thesis has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. This is being submitted to the Nagaland University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology. Candidate ().~~ (OINAM MOMOTON SINGH) Supervisor \~~~I ~~~,__ (PROF. A. LANU AO) (DR. KSHETRI RAJENDRA SINGH) Pro:~· tJeaJ Associate Professor r~(ltt ~ s.-< tr '•'!_)' ~ssociate <Professor f'l;-gts~·'l4i \ "'"~~1·, Oeptt of SodOIOGY Negelend unlY9fSitY HO:Lumeml Preface The theory of democracy tells that the people rule. -

June 15 Page 2

Imphal Times Supplementary issue 2 Editorial Contd. from previous issue Imphal, Thursday June 15, 2017 Mr. CM, it should be Manipur: The Boiling Bowl of Ethnicity By: Dr. Aaron Lungleng Rivers in Imphal and not The Meities attend his coronation ceremony to pay neighbors. Several times, neighboring up till the beginning of the 20th century. According to Iboongohal Singh, “The homage to him. Marjit refused to attend kingdom men and royals pay a visit to Whereas, the Nagas and Meiteis at that only Imphal River original inhabitants of Manipur were the the coronation, which offended the the friendly Naga villages; they were time had already set up a proper village Kiratas (some tribes of Nagas), by that Burmese king. Thus, he sends a large treated as an honored guest due to state on the other hand the Meitie had Chief Minister N. Biren Singh’s serious concern to time, Manipur valley was full of water” force under the command of General generations’ contacts through trade established their own kingdom. the flash flood, which had breached River Banks at (Singh, 1987:10). The present valley Maha Bandula to humble Marjit. Has even in the time of headhunting. Their The probability of the Kukis migrating many places, is indeed the need of the hour. There inhabitants (Imphal valley) were known human grateful attitude learnt sympathetic treatment cannot therefore upward from the Burma cannot be may be many reasons of the flash flood which had by different names by their neighbors Meetrabak/ would never face such be taken as conquest in any sense. -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume:04, Issue:01 "January 2019" POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE BRITISH AND THE MANIPURI RESPONSES TO IT IN 1891 WAR Yumkhaibam Shyam Singh Associate Professor, Department of History Imphal College, Imphal, India ABSTRACT The kingdom of Manipur, now a state of India, neighbouring with Burma was occupied by the Burmese in 1819. The ruling family of Manipur, therefore, took shelter in the kingdom of Cachar (now in Assam) which shared border with British India. As the Burmese also occupied the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam and the Cachar Kingdom threatening the British India, the latter declared war against Burma in 1824. The Manipuris, under Gambhir Singh, agreed terms with the British and fought the war on the latter’s side. The British also established the Manipur Levy to wage the war and defend against the Burmese aggression thereafter. In the war (1824-1826), the Burmese were defeated and the kingdom of Manipur was re-established. But the British, conceptualizing political economy, ceded the Kabaw Valley of Manipur to Burma. This delicate issue, coupled with other haughty British acts towards Manipur, precipitated to the Anglo- Manipur War of 1891. In the beginning of the conflict when the British attacked the Manipuris on 24th March, 1891, the latter defeated them resulting in the killing of many British Officers. But on April 4, 1891, the Manipuris released 51 Hindustani/Gurkha sepoys of the British Army who were war prisoners then giving Rupees five each. Another important feature of the war was the involvement of almost all the major communities of Manipur showing their oneness against the colonial British Government. -

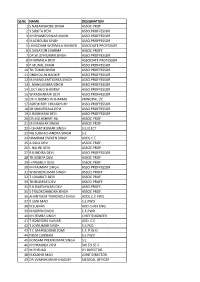

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

New Insights Into the Glorious Heritage of Manipur

VOLUME - TWO Chapter 5-B Sanskritization Process of Manipur Under King Garib Niwaz 239-270 Sairem Nilbir 1. Introduction 239 2. Charairongba as The First Hinduized King 239 3. Initiation of Garib Niwaz into Hinduism 240 4. Destruction of Umang Lai Deities & Temples 241 5. Identification of Gotras with Yeks/Salais 242 6. Introduction of a Casteless/J&raaless Hindu Society 243 7. Burning of Annals or Puyas 243 8. Identification of Manipuri Festivals with Hindu Festivals 246 9. Renaming the Kingdom as Manipur 247 10. Last Days of King Garib Niwaz 247 11. Conclusion 248 References & Notes 249 References 249 Notes 1. The Sanskritization -vs- Indianization Theses 250 2. Descent of Sanamahi Religion 253 (xxii) 3. Hinduism Reached its Apogee during Bhagyachandra's Reign 257 4. Transition from Pakhangba to Sanamahi Lineage 258 5. Sana-Leibak Manipur as Test-Tube of Religion & Identity 260 6. Manipuriness: Values to Defend 262 7. Oriental Happiness 268 "fables 5B-1: Gotras Made Convergent to Ye fc/Sa!ais 243 5B-2: Old Meitei Books Consigned to Flame by GaribNtwaz 244 Chapter 6 Rajarshi Bhagyachandra - The Royal Saint and Patriot 271-314 Dr. KManikchand Singh h Introduction 271 2. Burmese Invasion of 1758 272 3. Bhagyachandra - The Diplomatic Genius 274 4. Bhagyachandra's War with Burma,1764 277 5. Bhagyachandra in the Ahom Capital 278 6. Capture of Wild Elephants 279 7. The Return of Bhagyachandra 281 8. Further Conflict with Burma 283 9. Efficient Administrator 284 10. Unmatched Valour & Patriotism 286 11. Bhagyachandra's Dharma 287 12. Ras-Lila 289 13. Pilgrimage to Vrindavan 293 References, Further References & Notes References 295 Further References 297 Notes 1. -

Social Science Researcher (2020) 6 (1) Paper I.D

ISSN: 2319-8362 (Online) Social Science Researcher (2020) 6 (1) Paper I.D. 6.1.2 th th th Received: 15 December, 2019 Acceptance: 27 February, 2020 Online Published: 4 March, 2020 ROLE OF MANIPURIS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BARAK VALLEY OF ASSAM (1765-1900) * Author: Pukhrambam Sushma Devi Abstract: In the history of nineteenth century Cachar (now in Assam, India), Manipuris played a great role not only in the politics but also in the economy and society too. During the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826), the Manipur is living in the region assisted the British in expelling the Burmese from the soil of Cachar. They also took a lion’s share in developing the economy of Cachar by expanding and improving cultivable land of the valley. Manipur is also deeply in influenced in the society and culture of the Barak valley. But, so far, no scholar has tried to highlight a clear socio-economic and political role of the Manipur is in Cachar in its historic perspectives. This paper is, therefore, to fill up the missing part of the history of Cachar in northeast India. The source materials are archival, oral as well as secondary source books. Keywords: Manipuri, Manipur, Cachar, Barak Valley, British Administration, Colonial Study. 2.1 INTRODUCTION: In the history of nineteenth century Cachar (now in Assam, India), Manipuris played a great role not only in the politics but also in the economy and society too. During the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826), the Manipur is living in the region assisted the British in expelling the Burmese from the soil of Cachar. -

Summerhill 07-01-13.Pmd

Philosophy of History and the Historiography of Manipur GANGMUMEI KAMEI This paper is a brief review of the epistemology of history been described as ìthe sacred and mythological poemî and historiography. The history, historical knowledge, derived from Hindus religious myth and belief. Purana the philosophy of history, the mode of rational analysis cannot cover History5. Itihas is the more appropriate word or the scientific method constitute what is popularly for history. Another Sanskrit word ìVansavaliî meaning known as the Historical Method. The basic tenets of the geneology of the ruling families of principalities or Historical Method are the definition of history, nature kingdom is widely used. and objective of historical studies, discovery of the historical facts, the reconstruction of the historical past, THE CHRISTIAN THEOLOGICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY AND conceptualization, interpretation, generalization and periodization of the historical events. ST. AUGUSTINE: HISTORY AS A DIVINE PLAN The study of history has gone through many ages and What is the purpose of History? The Christian theological stages. As regards the definition of history, it started with historiography of Europe strongly emphasized that the the classical historians of the ancient Greece. The term purpose of history which proceeds according to the divine ìHistoryî originated with the Greek word, ìHistoriaî plan is the ultimate realization of the eternal will of God whose literal meaning was ìinquiryî. The great pioneer for spiritual redemption of man or punishment of man historians were Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus in the hands of God. Christian historiography of the 1 who wrote The Historiesî was regarded as the father of Middle Ages represented by St. -

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT in MANIPUR 1919-1949 DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Political Science S. M. A. W. CHISHTI Professor S. A. H. HAQOI

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN MANIPUR 1919-1949 iiBSTRACT OF THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN Political Science BY S. M. A. W. CHISHTI Under the Supervision of Professor S. A. H. HAQOI Head of the Department of Political Science FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH X&7B POLITICHL DEVELOPFtEM IN PlrtNlPUR, 1919-1949 The study deals with the political and constitutional deuelopments in the erstwhile princely State of C'lanipur from 1919 till its merger uith India in 1949. Bordered with Burma, she occupies one of the strategically situated states in the north-eastern region. In the uake of the political upheaval of 1891, Planipur lost her identity and became a protectorate of the British Government of India. Since the Flanipuri uprising of 1891 against the British Government, the^Kuki insurgency during 1917-19 uas the most significant political occurring dui-ing the entire period of the British rule in Manipur. The Kukis, one of the most powerful tribes of Fianipur, revolted against foreign domination. The administration uas very much upset by the disturbances in the hills. The Government felt considerably annoyed with frequent troubles which often resulted in losses of life and property. The Government could, however, bring the situation under control only in 1919, The experience of the Kuki rebellion made the British Government realise the inadequacy of the rules which wore framed for the administration cf flanipur State in 191G, The unrest among the Kacha Magas and the Kabul riagas of the north-uest of Manipur during the early l93CJs uas a turning point In the political hlctory of tribal rianlpur. -

Settlement History of the Manipuri in Barak Valley

RJPSS 2017 -Vol. 42, No.1 ISSN (P): 0258-1701 (e): 2454-3403 ICRJIFR IMPACT FACTOR 3.9819 Settlement History of The Manipuri in Barak Valley H. Basanta Kumar Singha Department of Sociology Maibang Degree College [email protected] Abstract: It’s an attempt to find out the migration and settlement history of Manipuris in this region. Settlement history is closely link with their present composite identity. Making conclusion of their emergence as distinct community in the valley by limiting only to 18th century may be a premature one. It may go beyond that. The author has used secondary resources such as Royal Chronicles, Gazetteers, Journals Magazines and relevant books in the study. The article shall confine only to the district of undivided Cachar, on the southern tip of Assam, which at present includes three separate districts, viz Cachar, Hailakandi and Karimganj. The plain area of these districts constitutes, what is called as Barak-Valley. It is located between the 92.15°E and 93.15°E longitudes and between the 28.8°N and the 25.8°N latitudes. The valley is surrounded by Manipur State in the East, North-Cachar Hills on the North, Mizoram in the South and Tripura and Sylhet (Bangladesh) in the West. Barak-Valley as a whole represents a number of heterogeneous communities, whose total population is 47,91,390 accoding to census 2011. They are living together for a long period of time. The numerous communities of Barak_Valley are : 1. Bengali (Both Hindu and Muslim) 2.Ex-tea Garden Labourers 3. Manipuri 4. -

Architecture of the Kangla Palace, Manipur

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 6, Ver.13 (June. 2017) PP 21-26 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Architecture of the Kangla palace, Manipur Dr. Sougrakpam Dharmen Singh, (Assistant Professor, Department of History, Thoubal College, Manipur, India) Abstract: The Ningthouja dynasty, who ruled from 1st century A.D. in Manipur, played an important role for the growth and development of the Kangla palace. They constructed forts, royal residence, roads, temples, coronation hall, excavated tanks and moats and other secular buildings. Among the ancient capitals Kangla was the most important because of its geographical location as well as religious matters. The archaeological remains of kangla give very valuable information about the art and architecture of Manipur. The paper is to find out new fact with the help of scientific methods and also to interpret literary sources in the light of the information gathered from field investigation. The sites of the remains were explored and studied the materials to finalise the facts. Emphasis has also been laid on the study of the general layout, ground plan and vertical feature of the structures. The present paper is based on the field investigation and literary sources. Key words:- Art, architecture, archaeology, ancient, citadel, capital, excavation, fort, moat, sacred, residency. I. INTRODUCTION Manipur is an ancient state, lies in the North-Eastern corner of India. The rich cultural heritage of Manipur is well known. Nongda Leiren Pakhangba, who ascended the throne in 33 A.D, founded the Ningthouja dynasty and Kangla was his capital. -

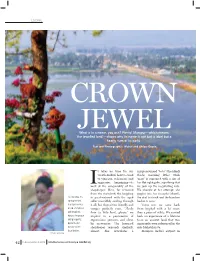

Manipur—Which Means ‘The Jewelled Land’—Shows Why Its Name Is Not Just a Label but a Hearty Sum of Its Parts

ESCAPE CROWN JEWELWhat is in a name, you ask? Plenty! Manipur—which means ‘the jewelled land’—shows why its name is not just a label but a hearty sum of its parts. Text and Photographs: Mukul and Shilpa Gupta t takes no time for our mispronounced “toda” (the Hindi ‘North-Indian’ hearts—used thoda, meaning little) while to vigorous, vehement, and ‘more’ is expressed with a rise of aggressive bargaining—to her flat right palm, signifying that Imelt at the congeniality of the we jack up the negotiating rate. shopkeeper. Here, far removed We chuckle at her attempt, she from the mainland, the haggling giggles into her innaphi (shawl), Lai Haraoba, the is good-natured with the aged the deal is struck and the bamboo spring festival, seller incredibly smiling through basket is ours. is a harmonious it all, her disposition friendly and Turns out, we came back blend of stylised temper perfectly even. “Thoda from Imphal with a lot more and ritualistic kam (a little less), please,” we than a piece of utility. We carried dances for peace implore in a pantomime of back an experience of a lifetime and prosperity, expressions, gestures, and silent from an ancient land that was performed in lip movement. The bemused apparently even referenced in the honour of the shopkeeper responds similarly, epic Mahabharata. local deities. almost. She articulates a Manipur, India’s outpost in Photo: Dinodia 42 February-March 2016 India Now Business and Economy n www.ibef.org ESCAPE the north-east, means the land of jewels. If ever there was an apt moniker, it is this.