Charles Rennie Mackintosh's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josef Hoffmann, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Their Contribution to the Decorative Arts in Fin- De-Siecle Glasgow and Vienna

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 4-15-2014 The Two Gentleman of Design: Josef Hoffmann, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and their Contribution to the Decorative Arts in Fin- de-Siecle Glasgow and Vienna Elizabeth Muir Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Muir, Elizabeth, "The Two Gentleman of Design: Josef Hoffmann, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and their Contribution to the Decorative Arts in Fin-de-Siecle Glasgow and Vienna" (2014). Honors Projects. 51. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/51 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Elizabeth Muir Major: History Research Honors The Two Gentleman of Design: Josef Hoffmann, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and their Contribution to the Decorative Arts in Fin-de-Siecle Glasgow and Vienna Dr. Horwitz April 15, 2014 In the twentieth century, two designers stood out as radicals: Josef Hoffmann of Vienna and Charles Rennie Mackintosh of Glasgow. -

Spring 2018 CELEBRATORY Issue: 150 Years Since the Birth Of

JOURNALISSUE 102 | SPRING 2018 CELEBRATORY ISSUE: 150 yearS SINce THE BIrtH OF CHarleS RENNIE MacKINtoSH, 1868–1928 JOURNAL SPRING 2018 ISSUE 102 3 Welcome Stuart Robertson, Director, Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society 4 Hon President’s Address & Editor’s Note Sir Kenneth Calman & Charlotte Rostek 5 Mackintosh Architecture 1968–2018 Professor Pamela Robertson on future-proofing the protection and promotion of Mackintosh’s built heritage. 9 9 Seeing the Light Liz Davidson gives a progress report on the restoration of The Glasgow School of Art. 12 The Big Box Richard Williams reveals the NTS’s big plans for The Hill House. 14 Mackintosh at the Willow Celia Sinclair shares the latest on the restoration work. 16 Authentic? 14 Michael C. Davis takes a timely look at this topical aspect of building conservation. 19 A Bedroom at Bath Dr Trevor Turpin explores this commission by Mackintosh. 23 An Interview with Roger Billcliffe Stuart Robertson presents Part 1 of his fascinating interview with Roger Billcliffe. 32 The Künstlerpaar: Mackintosh, Macdonald & The Rose Boudoir Dr Robyne Calvert explores love and art in the shared lives of this artistic couple. 23 36 The Mackintosh Novel Karen Grol introduces her biographical novel on Mackintosh. Above, Top: Detail of prototype library bay for GSA. Photo Alan MacAteer Middle: Detail of front signage for 38 Observing Windyhill Mackintosh at the Willow. Ruairidh C. Moir discusses his commission to build a motor garage at Windyhill. Photo Rachel Keenan Photography Bottom: Frances Macdonald, Ill Omen 40 Charles Rennie Mackintosh – Making the Glasgow Style or Girl in the East Wind with Ravens Passing the Moon, 1894, Alison Brown talks about the making of this major exhibition. -

This Document Is an Extract from Engage 31: the Past in the Present, 2012, Karen Raney (Ed.)

This document is an extract from engage 31: The Past in the Present, 2012, Karen Raney (ed.). London: engage, the National Association for Gallery Education. All contents © The Authors and engage, unless stated otherwise. www.engage.org/journal 78 This is the Time 79 Past, present and future at The Glasgow School of Art Jenny Brownrigg Exhibitions Director, The Glasgow School of Art The Mackintosh Museum, built in 1909, is at the Glamour’, 5 all flicker tantalisingly on the wall, heart of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterwork, or can perpetually be captured as media The Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Building. soundbites. Mackintosh himself is omnipresent in With its high level of architectural detail inside and the city and beyond as an easily recognisable style outside, the museum is the antithesis of the ‘white in merchandising and souvenirs. It is even possible cube’. This essay will explore the ways in which the to buy a ‘Mockintosh’ moustache from the GSA contemporary exhibitions programme for the tour shop. gallery space within this iconic building can create a The Mackintosh building has never been emptied critical exchange between past, present and future. of its educational activities to become a museum. For someone standing here in the present moment, In this living, working building with its community the architect and the presence of generations of of students and staff, past, present and future exist staff, students and visitors who have moved together in a continuum. Even the lights that through the building could represent the shadows Mackintosh had made for the centre of the library in Plato’s Cave. -

11—17Th September 2017 116 Buildings 50 Walks & Tours a Celebration of Glasgow’S Talks, Events Architecture, Culture & Heritage

Get into buildings and enjoy free events. 11—17th September 2017 116 Buildings 50 Walks & Tours A celebration of Glasgow’s Talks, Events architecture, culture & heritage. & Children’s Activities glasgowdoorsopendaysfestival.com In association with: Photography Competition Send us your photos from the festival and win prizes! Whether you’re a keen instagrammer or have some serious photography kit you could be the winner of some fantastic prizes! Enter by sending your hi-res images to [email protected] or by tagging @glasgowdoorsopendaysfestival on Instagram with the hashtag #GDODFphotos For further details, including our competition categories see glasgowdoorsopendaysfestival.com This competition is partnered with Glasgow Mackintosh www.glasgowmackintosh.com THINGS TO KNOW Every effort was made to ensure details in this brochure were correct at the time of going to print, but the programme is subject to change. For updates please check: www.glasgowdoorsopendaysfestival.com, sign up to our e-bulletins and follow our social media. GlasgowDoorsOpenDays GlasgowDOD Hello glasgowdoorsopendaysfestival Timing Check individual listings for opening hours and times. Access Due to their historic or unique nature, we regret that some venues are not fully accessible. Access is indicated in each listing Now in its 28th year, Glasgow Doors Open and in more detail on our website. A limited number of BSL interpreters are available to Days Festival is back to throw open the book for certain walks & tours, please visit our doors of the city in celebration of Glasgow’s website for details on eligible walks & tours and architecture, culture and heritage. Join us how to book. Electronic Notetaking will be available for a number of our talks at our 11-17th September to get behind the scenes pop-up festival hub at St. -

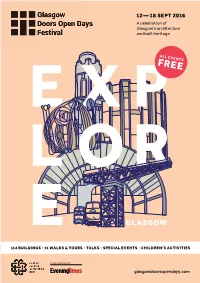

Glasgow’S Architecture and Built Heritage

12 — 18 SEPT 2016 A celebration of Glasgow’s architecture and built heritage ALL EVENTS FREE GLASGOW 114 BUILDINGS • 51 WALKS & TOUrs • TALKS • SPECIAL EVENTS • CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES In association with: glasgowdoorsopendays.com THINGS TO KNOW Details in this brochure were correct at the time of going to print, PHOTOGRAPHY but the programme is subject to change. For updates please check COMPETITION WIN glasgowdoorsopendays.com, sign up to PRIZES! H E our e-bulletin and follow our social media. GlasgowDoorsOpenDays GlasgowDOD GlasgowDoorsOpenDays TIMINGS Check individual listings for opening hours and event times. Send us your photos of AccESS L L O Due to their historic or unique nature, Doors Open Days 2016 we regret that some venues are not fully accessible. Access is indicated in each and win some fantastic listing and in more detail on our website. prizes! FOR THE faMILY Glasgow Doors Open Days is The majority of buildings and events are fun for children and we’ve highlighted back for the 27th year, celebrating key family activities on page 34. We’ve CATEGORIES also put together a dedicated children’s Inspired by Mackintosh | People and Place | Glasgow’s unique architecture programme which will be distributed to Architectural Detail | Cityscape | Behind the Scenes and built heritage! This year Glasgow primary schools in late August. YOU COULD WIN VOLUNTEERS – £250 voucher to spend at Glasgow Architectural Salvage we’re part of the national Festival Doors Open Days is made possible – A year’s subscription to Scots Heritage Magazine -

Muddle on Mackintosh

Muddle on Mackintosh John McKean looks below the shiny surface of the latest handsome tome on C R Mackintosh to find confusion and shake scholarly integrity 16.07.2010 An astonishing number of books have the title ‘Charles Rennie Mackintosh’. A glance at Amazon quickly shows readers’ understandable confusions between them. Can publishers really not accept more creative titles to distinguish very different volumes? As James Macaulay’s handsome and beautifully produced addition (Charles Rennie Mackintosh, WW Norton, 275 pages, hardback, £42) now tops the pile, the potential reader deserves some help in relating the meat to what it says on the tin. A first clue is offered by his 246 illustrations. Nearly a third show Mackintosh architecture. A quarter are in his hand – mostly in architectural drawings; but just 20 others cover all his huge range of flower drawings, graphic and decorative work and his paintings. Just under half of the book’s images, however, show the work of others. Many of these illustrate the Glasgow of Mackintosh’s youth, some show the Glasgow going up around him, while others illustrate non- architectural the work of those close to him during his years in Glasgow. But one soon senses a ‘little Glaswegian’ mentality developing. Mackintosh, we are told “would have been shocked” on seeing Raimondo D’Aronco fine building for the Turin 1902 exhibition. But, as it was not in Glasgow, we are not shown it nor is the architect even named. Nor are we shown anything by James MacLaren, surely an important influence on Mackintosh; not being Glaswegian this architect is never even mentioned. -

Journal Rev 923 1544

Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was period for what he thought might be a established in 1973 to promote and encourage The Mackintosh Church At Queen’s Cross temporary appointment! Drew has given awareness of the Scottish architect and designer, 870 Garscube Road, Glasgow G20 7EL sterling service and has been a great Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Tel: +44 (0)141 946 6600, Fax: +44 (0)141 946 7276 ambassador for the Society. His weekly Email: [email protected], www.crmsociety.com visits to Queen’s Cross will be missed. The Society’s core aims are to: www.mackintoshchurch.com • Support the conservation, preservation, Our Volunteer coordinator Karin Otto maintenance and improvement of buildings returned to the US at the end of September. and artefacts designed by Charles Rennie Board Of Trustees Karin has done an amazing job in developing Stuart Robertson – Executive Director and Secretary Mackintosh and his contemporaries. new volunteers and helping setup a Evelyn Silber – Chair volunteer structure, creating new roles and • Advance public education in the works of Alison Brown job descriptions. Karin will be missed, but Charles Rennie Mackintosh by means of Judith Patrickson – Honorary Treasurer we hope she will still be able to contribute exhibitions, lectures and productions of an Deirdre Bernard, Charles Hay, from the other side of the pond. educational nature. Mairi Bell, Catriona Reynolds, Peter Trowles • Maintain and develop The Society’s As you will see from Evelyn’s comments, Headquarters at Queen’s Cross there will be some radical changes in the • Service and develop the membership of The Hon President operation of the Society and the Mackintosh Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden KT Society. -

VOLUME 98 SPRING 2014 Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society

JOURNALVOLUME 98 SPRING 2014 Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was established in 1973 to promote and encourage Mackintosh Queen’s Cross awareness of the Scottish architect and designer, 870 Garscube Road, Glasgow G20 7EL Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Tel: +44 (0)141 946 6600 Email: [email protected] The Society’s core aims are to: www.crmsociety.com www.mackintosh.org.uk • Support the conservation, preservation, maintenance and improvement of buildings Board Of Trustees and artefacts designed by Charles Rennie Stuart Robertson – Executive Director and Secretary Mackintosh and his contemporaries. Carol Matthews – Chair • Advance public education in the works of Catriona Reynolds - Vice Chair Charles Rennie Mackintosh by means of Judith Patrickson – Honorary Treasurer exhibitions, lectures and productions of an Mairi Bell, Alison Brown, Pamela Freedman, educational nature. Garry Sanderson and Sabine Wieber • Maintain and develop The Society’s Headquarters at Queen’s Cross Hon President • Service and develop the membership of The Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden KT Society. • Sustain and promote the long-term viability Hon Vice Presidents of The Society. Roger Billcliffe, Baillie Liz Cameron Patricia Douglas MBE, Prof. Andy McMillan The Society has over 1200 members across the world with active groups in Glasgow, London and the South East, Japan, and an associate group in Port Vendres, Staff Director: Stuart Robertson France. Business & Events: Dylan Paterson p/t Retail Officer: Irene Dunnett p/t There has never been a better time to join the Society. Our members - people like you who are passionate about the creative genius of Mackintosh - are helping Volunteer Posts shape our future. -

Re-Evaluating the Glasgow Girls. a Timeline of Early Emancipation at the Glasgow School of Art. Alison Brown, Curator of Europea

Strand 1. Breaking the Art Nouveau Glass Ceiling: The Women of Art Nouveau Re-evaluating the Glasgow Girls. A timeline of early emancipation at the Glasgow School of Art. Alison Brown, Curator of European Decorative Art from 1800, Glasgow Museums, Glasgow Life Abstract This paper will delve into the context for the sudden explosion of female creativity at the Glasgow School of Art from about 1890. It aims to place the 'Glasgow Girls' and their work - particularly those studying and working in the School's Technical Art Studios and in the decorative arts and design between 1890 and 1910 - within a wider chronological picture within Glasgow. This chronological approach produces pleasant surprises: the dynamics of contemporaries, friendships and shared exhibition and studio spaces paint a broader picture of collaboration. Visually we see influences for the formation of the 'Glasgow Style'. What emerges from this timeline is a design history based on British education policy, wealth and class, industrial ambition and the sometimes surprisingly progressive views of some of the male elite then running the City and the Art School. Keywords: The Glasgow Girls, Art education, technical instruction, Glasgow School of Art (GSA), needlework, metalwork, Jessie Newbery, Jessie Marion King, Ann Macbeth, Dorothy Carlton Smyth 'The Glasgow Girls' is the popular collective title now given to the women who studied and worked at the Glasgow School of Art from 1880 until 1920. It was first used prominently in a feminist art historical context by Jude Burkhauser in 1988 for a small exhibition she curated at the Glasgow School of Art based on her postgraduate studies. -

Pyroarchitectures Construction by Combustion

Pyroarchitectures construction by combustion by Martin Macdonald A thes! submitted to the Faculty o" Graduate and Post Doctoral A#airs In partial ful$lment o" the requirements for the degree o" Master in Architecture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Martin Macdonald Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required !nal revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii ABSTRACT: Pyroarchitectures; construction by combustion Pyroarchitectures describe architecture produced by the product of !re. This thesis proposes a conceptual system to engage with burned buildings, their narrative, and a co-existence between a burned artifact and contemporary architecture. A provisional, reciprocal partnership between two parts; burned artifact and contemporary intervention. The system examines the tension between burned existing context and cast new content which traces and records the unpredictability !re has on objects. This thesis utilizes casting as a methodology to preserve and engage a burned artifact; it demonstrates layering and physical indexing with a focus on time and memory. It further explores the possibility to preserve a moment in time to document the form of architecture in spontaneous "ux. The Glasgow School of Art has consumed two !res in its lifetime and is used as a case study to explore the relationship between !re and architecture, and pose the question; how can combustion inform construction? iv v Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Sheryl Boyle for her guidance and continually challenging me throughout my thesis. -

VOLUME 99 WINTER 2014/15 Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society

JOURNALVOLUME 99 WINTER 2014/15 Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society was established in 1973 to promote and encourage Mackintosh Queen’s Cross awareness of the Scottish architect and designer, 870 Garscube Road, Glasgow G20 7EL Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Tel: +44 (0)141 946 6600 Email: [email protected] The Society’s core aims are to: www.crmsociety.com www.mackintosh.org.uk • Support the conservation, preservation, maintenance and improvement of buildings Board Of Trustees and artefacts designed by Charles Rennie Stuart Robertson – Executive Director and Secretary Mackintosh and his contemporaries. Carol Matthews – Chair • Advance public education in the works of Alison Brown - Vice Chair Charles Rennie Mackintosh by means of Judith Patrickson – Honorary Treasurer exhibitions, lectures and productions of an Mairi Bell, Helen Crawford, Pamela Freedman, educational nature. Pamela Robertson and Garry Sanderson • Maintain and develop The Society’s headquarters at Queen’s Cross Hon President • Service and develop the membership of The Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden KT Society. • Sustain and promote the long-term viability Hon Vice Presidents of The Society. Roger Billcliffe, Baillie Liz Cameron & Patricia Douglas MBE The Society has over 1200 members across the world Staff with active groups in Glasgow, London and the South Director: Stuart Robertson East, Japan, and an associate group in Port Vendres, Business & Events: Dylan Paterson p/t France. Heritage Officer (Intern): Sven Burghardt p/t Retail Officer: Irene Dunnett p/t There has never been a better time to join the Society. Our members - people like you who are passionate about the creative genius of Mackintosh - are helping Volunteer Posts shape our future. -

Mackintosh, Muthesius, and Japan Industrial City

Found in Translation: inform his students of the range of products manufactured in a modern Mackintosh, Muthesius, and Japan industrial city. From Glasgow, therefore, went examples of Scottish wools, sugar refining and Lucifer matches, as well as fire-clay bricks, gas Neil Jackson tar and potash.4 To Glasgow, by comparison, came thirty-one packing The leading Japanese architect Isozaki Arata has observed that, ’A cases containing 1,150 items of contemporary art-wares ranging from Japanese person looking at [Mackintosh’s] work is immediately struck wood-block print paper to silk brocade and even full costumes. These by how “Japanese” his designs are. The simplicity needs no explanation. were exhibited in the Corporation Galleries on Sauchiehall Street and It is amazing how he has grasped the essence of Japanese aesthetics.’1 in the City Industrial Museum in Kelvingrove Park.5 Three years later the Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s (1868-1928) ‘grasping’ of the Japanese Corporation Galleries hosted the Oriental Art Loan Exhibition showing a aesthetic did not come by chance, nor did it come as the result of a visit range of pieces including lacquer-work, Japanese bronzes, textiles and to Japan, for he never went there. It was, as this essay attempts to show, screens, gathered from private collections, the South Kensington Museum the result of the time and the place of his education and experience as and Messrs Liberty’s of London.6 Then early in 1882 the Glasgow-born an architect – Glasgow, at the end of the 19th century – and his close architect and ornamentalist, Christopher Dresser returned to the city to friendship with a German architect, Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927).