IEMS Lahore City Report Home-Based Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: JRSP, Vol

Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: JRSP, Vol. 58, No 2 (April-June 2021) Samina Yasmeen1 Fozia Umar2 Religious Extremism and Sectarianism in Pakistan: An Appraisal Abstract Pakistan, which was created on the basis of religion have had to face sectarian violence and religious intolerance from the very beginning. This article offers an in-depth analysis of sectarianism and religious intolerance and their direct role in the current chaotic state of Pakistan. This article revolves around the two main research questions including the role of religion in the state of Pakistan as well as the evidences depicting sectarian violence in Pakistan. The main objective is to analyze the future situation of the rampant sectarian condition in the society and to study the role of Pakistan’s government so far. Qualitative methodology using primary as well as secondary sources are used to gather the data. Post-dictatorship era, after 2007, is being analyzed in this article, keeping in view the history of sectarian violence, future and stability of the state. Last comments lead to the recommendations and ways to tackle the sectarian divide and religious extremism. The researchers conclude that religion is core at the Pakistan’s nationalism however, religious extremism weakens national and social cohesion and also divides loyalties. There is a need for strict blasphemy laws, banning hate speeches which incites the violence and most importantly, eradicating poverty and unemployment, so no foreign elements can bribe anyone for sectarian terror within the state. Introduction Pakistan was a country that was created on the basis of religion, its main goal was to provide a homeland for Muslims where they will live in freedom and harmony and it was established that it will be governed according to the principles set by Islam. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

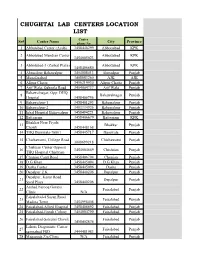

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors ASIA PAPER November 2008 Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Papers from a Conference Organized by Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and the Institute of Security and Development Policy (ISDP) in Islamabad, October 29-30, 2007 Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors © Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Islamabad Policy Research Institute House no.2, Street no.15, Margalla Road, Sector F-7/2, Islamabad, Pakistan www.isdp.eu; www.ipripak.org "Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan" is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. Through its Silk Road Studies Program, the Institute runs a joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This report is published by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and is issued in the Asia Paper Series with the permission of IPRI. -

History of Sectarianism in Pakistan: Implications for Lasting Peace

al Science tic & li P o u Asma and Muhammad, J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2017, 5:4 P b f l i o c Journal of Political Sciences & Public l DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000291 A a f n f r a u i r o s J Affairs ISSN: 2332-0761 Research Article Open Access History of Sectarianism in Pakistan: Implications for Lasting Peace Asma Khan Mahsood* Department of Political Science, Gomal University, Dera Ismail Khan, KPK, Pakistan *Corresponding author: Asma Khan Mahsood, Department of Political Science, Gomal University, Dera Ismail Khan, KPK, Pakistan, Tel: +92 51 9247000; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: June 20, 2017; Accepted date: September 20, 2017; Published date: September 26, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Asma Khan Mahsood, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Sectarianism is an issue that is badly damaging the society. In history we will find many of its instances but since the last three decades the pattern of events highlights that the issue has becomes intricate. The society of Pakistan is by and large divided on ethnic basis and sectarian divide further added fuel to the fire. This issue is badly damaging the society on economic political as well as on societal basis. The implications of sectarian violence are posing great threats to the peace process in the country. This intricate issue demands clarity and comprehension. Keywords: Pakistan; Sectarian violence; Government; Religion; ALLAH and his Messenger Muhammad (SAW) [2]. -

![Life Story of Sant Attar Singh Ji [Of Mastuana Sahib]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9856/life-story-of-sant-attar-singh-ji-of-mastuana-sahib-679856.webp)

Life Story of Sant Attar Singh Ji [Of Mastuana Sahib]

By the same author : 1. Sacred Nitnem -Translation & Transliteration 2. Sacred Sukhmani - Translation & Transliteration 3. Sacred Asa di Var - Translation & Transliteration 4. Sacred Jap Ji - Translation & Transliteration 5. Life, Hymns and Teachings of Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji 6. Stories of the Sikh Saints "'·· 7. Sacred Dialogues of Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji 8. Philosophy of Sikh Religion (God, Maya and Death) 9. Life Story of Guru Gobind Singh Ji & His Hymns 10. Life Story of Guru Nanak Dev Ji & Bara-Maha 11. Life Story of Guru Amardas Ji ,, 12. Life Story of Bhagat Namdev Ji & His Hymns t' 13. How to See God ? 14. Divine Laws of Sikh Religion (2 Parts) L' LIFE STORY OF SANT ATTAR SINGH JI [OF MASTUANA SAHIB] HARBANS SINGH DOABIA SINGH BROS. AMRITSAR LIFE STORY OF SANT ATTAR SINGH JI by HARBANS SINGH OOABIA © Author ISBN 81-7205-072-0 First Edition July 1992 Second Edition September 1999 Price : Rs. 60-00 Publishers : SINGH BROTHERS, BAZAR MAI SEWAN, AMRITSAR. Printers: PRINTWELL, 146, INDUSTRIAL FOCAL POINT, AMRITSAR. CONTENTS -Preface 7 I The Birth and Childhood 11 II Joined Army-Left for Hazur Sahib without leave 12 III Visited Hardwar and other places 16 IV Discharge from Army-Then visited many places-Performed very long meditations 18 V Some True Stories of that pedod 24 VI Visited Rawalpindi and other places 33 VII Visited Lahore and Sindh and other places 51 VIII Stay at Delhi-Then went to Tam Tarm and Damdama Sahib 57 IX Visit to Peshawar, Kohat etc. and other stories 62 X Visit to Srinagar-Meeting with Bhai Kahan Singh of Nabha- -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

LAHORE HI Ill £1

Government of Pakistan Revenue Division Federal Board of Revenue ***** Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019. NOTIFICATION (Income Tax) S.R.O. 9^ (I)/2019.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 121(I)/2019 dated the Is' February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas or categories of Lahore specified in column (2) thereof. (2) The value for residential and commercial superstructure shall be — (a) Rs.1500 per square foot if the superstructure is upto five years old; and (b) Rs.1000 per square foot if the superstructure is more than five years old. (3) In order to determine the value of constructed property, the value of open plot shall be added to the value worked out at sub-paragraph (2) above. (4) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. LAHORE .-r* ALLAMA IQBAL TOWN S. Area Value of Residential Value of No property per maria Commercial (in Rs.) property per maria (in Rs.) HI ill £1 (41 1 ABDALIAN COOP SOCIETY 852,720 1,309,000 2 ABADI MUSALA MOUZA MUSALA 244,200 447,120 3 ABID GARDEN ABADI MUSALA 332,970 804,540 4 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 564,960 1,331,000 SOCIETY MOUZA KANJARAN 5 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 746,900 1,326,380 SOCIETY MOUZA IN SHAHPUR KHANPUR 6 AGRICHES COOP SOCIETY 570,900 1,039,500 7 AHBAB COLONY 392,610262,680 8 AHMAD SCHEME NIAZ BAIG 390,443 800,228 -

![C$) *!! Tc UVWV TV UVR] @< U](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1347/c-tc-uvwv-tv-uvr-u-801347.webp)

C$) *!! Tc UVWV TV UVR] @< U

6 7 > 3 *! ? )! ? ? RNI Regn. No. CHHENG/2012/42718, Postal Reg. No. - RYP DN/34/2013-2015 .0!:.",23 1#-#-8 "+ (1/0$ B -""4"" 64363" C4; 1"C4,." 3"6-6.4=5 1-=61-14"5; 5 -4 3"4".66 6" /$ ,44";- =;C ;4-;; -43,;- 3"-;34 -C3";13DC53 @6 +(90..# /#/ @ ) " * 5*1818; ,15 4"53"6- about the other deals given the Pinaka missile systems will + 4"53"6- " # !$ go-ahead, officials said weapon enable raising additional mid volatile situation on systems and equipment will be regiments over and above the fter a spooky June that saw & '(!) Athe Line of Actual Control manufactured in India involv- ones already inducted by the Aa three-fold rise in Covid- (LAC) in Ladakh, the Defence ing Indian defence industry Army. 19 cases from 2 lakh to 6 lakh, Acquisition Council (DAC) with participation of several India’s doubling rate — a glob- chaired by Defence Minister Micro, Small and Medium ally adopted yardstick to gauze Rajnath Singh on Thursday Enterprises (MSME). the acceleration of the outbreak approved defence deals worth “The Indigenous content in — stands fastest among the first over 38,900 crore. They some of these projects is up to 15 worst-affected countries. include acquisition of 33 front- 80 per cent of the project cost. In simple terms, the num- line fighter jets besides missiles A large number of these pro- ber of cases is rising much and ammunition. jects have been made possible faster in India than other worst- The approvals for procur- ed cost of 10,730 crore,” meant to replace the aircraft due to Transfer of Technology ! affected nations. -

LAHORE HI Ill £1

Government of Pakistan Revenue Division Federal Board of Revenue ***** Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019. NOTIFICATION (Income Tax) S.R.O. 9^ (I)/2019.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 121(I)/2019 dated the Is' February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas or categories of Lahore specified in column (2) thereof. (2) The value for residential and commercial superstructure shall be — (a) Rs.1500 per square foot if the superstructure is upto five years old; and (b) Rs.1000 per square foot if the superstructure is more than five years old. (3) In order to determine the value of constructed property, the value of open plot shall be added to the value worked out at sub-paragraph (2) above. (4) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. LAHORE .-r* ALLAMA IQBAL TOWN S. Area Value of Residential Value of No property per maria Commercial (in Rs.) property per maria (in Rs.) HI ill £1 (41 1 ABDALIAN COOP SOCIETY 852,720 1,309,000 2 ABADI MUSALA MOUZA MUSALA 244,200 447,120 3 ABID GARDEN ABADI MUSALA 332,970 804,540 4 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 564,960 1,331,000 SOCIETY MOUZA KANJARAN 5 ADJOINING CANAL BANK ALL 746,900 1,326,380 SOCIETY MOUZA IN SHAHPUR KHANPUR 6 AGRICHES COOP SOCIETY 570,900 1,039,500 7 AHBAB COLONY 392,610262,680 8 AHMAD SCHEME NIAZ BAIG 390,443 800,228