AC Course-Descriptio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Calendar 2020–2021

ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020 2021 1 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020–2021 The Board of Governors, the Senate, and the Administration of Redeemer University reserve the right to make changes in this calendar without prior notice. When academic programs and degree requirements are altered, the student must adhere to the calendar in effect for the academic year in which he or she was admitted to Redeemer, unless otherwise authorized by the university. 1 Table of Contents Academic Schedule 2020–21 ................................................5 Fees and Payments ..............................................................21 General Information ...............................................................6 Tuition, Food and Housing ..............................................................21 Mission and Vision Statement ..........................................................6 Student Fees ....................................................................................21 Institutional Purpose .........................................................................6 Special Fees .....................................................................................21 Statement of Basis and Principles......................................................6 Housing and Enrolment Deposit ......................................................22 Educational Guidelines .....................................................................7 Payments .........................................................................................22 Institutional -

Course Descriptions 2008/2009

Course Descriptions 2008/2009 AUGUSTINE COLLEGE faith seeking understanding 18 Blackburn Avenue, Ottawa, Canada K1N 8A3 (613) 237 9870 | fax (613) 237 3934 www.augustinecollege.org | CONTENTS Accreditation, 3 Credit Transfer, 4 Answers to a Few Common Questions, 5 Academic Requirements, 6 Courses Forming the Program, 8 1 Beginning Latin, 8 2 Philosophy In Western Culture, 9 3 Art In Western Culture, 11 4 Science, Medicine & Faith, 15 5 Music & Culture in the Christian West, 21 6 Literature In Western Culture, 23 7 Reading the Scriptures, 26 8 Trivium Seminar, 30 9 Book of the Semester, 32 Class Schedule, 34 Calendar of Events, 35 Academic Deadlines, 36 2 N A T U R E O F PROGRAM | Liberal Arts / Western Culture LEVEL OF STUDY | Full-Time Post-secondary / College ACADEMIC YEAR OF S TUDY ENTERED AT AC | Year 1 of 1-year program D A T E S O F PROGRAM | Start: September7, 2008 Completion: April 25, 2009 HOURS OF INSTRUCTION PER WEEK | 21 ACCREDITATION ugustine College is a small, private, not-for-profit college founded in 1997 that operates on an academic par A with many prestigious colleges and universities in Canada and the United States. As you may know, “Canada has no formal system of institutional accreditation,” as explained by the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, a national organization for the support of Canada‟s universities.1 In Canada “there is no federal ministry of education or formal accreditation system. Instead, membership in the AUCC, coupled with the university‟s provincial government charter, is generally deemed the equivalent.”2 However, this provides an accreditation equivalent for only a portion of Canada‟s universities: specifically, those with “an enrolment of at least 500 FTE students enrolled in university degree programs.”3 As we are by intention a small liberal-arts college conceived to offer an educational alternative to the large university, our enrolment will always be below that number. -

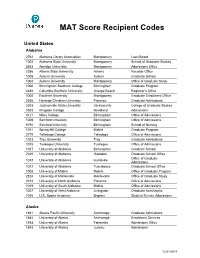

MAT Score Recipient Codes

MAT Score Recipient Codes United States Alabama 2762 Alabama Library Association Montgomery Loan Board 1002 Alabama State University Montgomery School of Graduate Studies 2683 Amridge University Montgomery Admissions Office 2356 Athens State University Athens Records Office 1005 Auburn University Auburn Graduate School 1004 Auburn University Montgomery Office of Graduate Study 1006 Birmingham Southern College Birmingham Graduate Program 4388 Columbia Southern University Orange Beach Registrar’s Office 1000 Faulkner University Montgomery Graduate Enrollment Office 2636 Heritage Christian University Florence Graduate Admissions 2303 Jacksonville State University Jacksonville College of Graduate Studies 3353 Kingdom College Headland Admissions 4121 Miles College Birmingham Office of Admissions 1009 Samford University Birmingham Office of Admissions 9794 Samford University Birmingham School of Nursing 1011 Spring Hill College Mobile Graduate Program 2718 Talladega College Talladega Office of Admissions 1013 Troy University Troy Graduate Admissions 1015 Tuskegee University Tuskegee Office of Admissions 1017 University of Alabama Birmingham Graduate School 2320 University of Alabama Gadsden Graduate School Office Office of Graduate 1018 University of Alabama Huntsville Admissions 1012 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa Graduate School Office 1008 University of Mobile Mobile Office of Graduate Program 2324 University of Montevallo Montevallo Office of Graduate Study 2312 University of North Alabama Florence Office of Admissions 1019 University -

List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017

Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 1ST NATIONS TECH INST-LOYALIST COLL Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory ON Canada 5TH WHEEL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NEW LISKEARD NEW LISKEARD ON Canada A1 GLOBAL COLLEGE OF HEALTH BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOG MISSISSAUGA ON Canada AALBORG UNIVERSITETSCENTER Aalborg Foreign Prov Denmark AARHUS UNIV. Aarhus C Foreign Prov Denmark AB SHETTY MEMORIAL INSTITUTE OF DENTAL SCIENCE KARNATAKA Foreign Prov India ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY Aberystwyth Unknown Unknown ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIV. Abilene Texas United States ABMT COLLEGE OF CANADA BRAMPTON ON Canada ABRAHAM BALDWIN AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE Tifton Georgia United States ABS Machining Inc. Mississauga ON Canada ACADEMIE CENTENNALE, CEGEP MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE CHARPENTIER PARIS Paris Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE CONCEPT COIFFURE BEAUTE Repentigny QC Canada ACADEMIE D'AMIENS Amiens Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE DE COIFFURE RENEE DUVAL Longueuil QC Canada ACADEMIE DE ENTREPRENEURSHIP QUEBECOIS St Hubert QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASS. ET D ORTOTHERAPIE Gatineau (Hull Sector) QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE ET D ORTHOTHERAPIE GATINEAU QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE DRUMMONDVILLE Drummondville QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE LANAUDIERE Terrebonne QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE QUEBEC Quebec QC Canada ACADEMIE DE SECURITE PROFESSIONNELLE INC LONGUEUIL QC Canada Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z ACADEMIE DECTRO INTERNATIONALE Quebec QC Canada Académie des Arts et du Design MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE DES POMPIERS MIRABEL QC Canada Académie Énergie Santé Ste-Thérèse QC Canada Académie G.S.I. -

Maria Gabankova

1 Maria Gabankova www.paintinggallery.net e-mail: [email protected] Curriculum vitae Ontario College of Art & Design Position Associate professor Program Drawing & Painting, Faculty of Art 1. General Information A. Education: 1997 Sculpture with Evan Penny, Toronto School of Art. 1982 Sculpture I and II with Heinz Klassen, Fraser Valley College, Abbotsford. 1979-1980 The Art Students League of New York. Studied with G. Rehberger, F. Mason, R. B. Hale, D. Leffel. Copied paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (after Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, F. Hals and Rembrandt). 1975-1980 Apprenticeship with artists Mr. J. Gabanek and Mrs A. Laník-Gabanek 1975-1977 Vancouver School of Art. Graduated in printmaking. Awarded the Helen Pitt scholarship twice. 1974 School of Art and Design, Montreal. 1970-1971 Studies at University of British Columbia Department of Fine Arts, Vancouver 1970 Graduation from Kitsilano High School, Vancouver. 1966-1968 Part-time studies at the Ostrava Art School B. Academic Appointments 2010 and 1997 Florence Campus program coordinator 2004 Redeemer University College, Fall term. 1998 till present MFA in Drawing and Painting Program - Norwich University, Vermont, artist teacher 1990 till present: Ontario College of Art: Drawing and Painting, Faculty of Art 1996 Realist Academy, Seattle, WA, Course in Figure and Drapery 1985-1990 Etobicoke Art Centre Continuing education courses in drawing and painting throughout Toronto 1985-1989 Oil painting at Seneca College, Toronto 1981-1983 Drawing and painting at Fraser Valley College, Abbotsford 1978-1983 Private classes in Vancouver, figure drawing, painting and portraiture 1976-1979 Drawing painting, printmaking courses at Burnaby Art Centre and at Malaspina Printmakers Society, Vancouver C. -

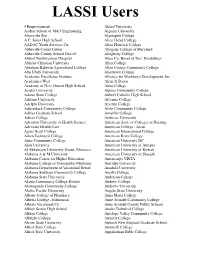

LASSI Users Master List

LASSI Users 4 Empowerment Alfred University Aarhus School of M&T Engineering Algoma University Above the Bar Algonquin College A.C. Jones High School Alice Lloyd College AADAC Youth Services Ctr Allan Hancock College Abbeville Career Center Allegany College of Maryland Abbeville County School Dist 60 Allegheny College Abbott Northwestern Hospital Allen Co. Board of Dev. Disabilities Abilene Christian University Allen College Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Allen County Community College Abu Dhabi University Allentown College Academic Excellence Institute Alliance for Workforce Development, Inc. Academics West Allyn & Bacon Academy of New Church High School Alma College Acadia University Alpena Community College Adams State College Althoff Catholic High School Addams University Alvernia College Adelphi University Alverno College Adirondack Community College Alvin Community College Adizes Graduate School Amarillo College Adrian College Ambrose University Adventist University of Health Science American Assn. of Colleges of Nursing Advocate Health Care American College - Arcus Agnes Scott College American International College Aiken Technical College American River College Aims Community College American University DC Ajou University American University of Antigua Al Akhawayn University, Ifrane, Morocco American University of Kuwait Alabama A & M University American University of Sharjah Alabama Center for Higher Education Americorps VISTA Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine Amridge University Alabama Department of Vocational Rehab -

Institutions Eligible to Participate in the 2017 Core Data Service * 2016 CDS Participant

Institutions Eligible to Participate in the 2017 Core Data Service * 2016 CDS Participant A.T. Still University of Health Sciences American International College Aalto University American Jewish University Aaniiih Nakoda College American Public University System Abilene Christian University* American River College ABO Akademi University American Samoa Community College Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College American Sentinel University Academy of Art University American University* Acadia University American University of Beirut* Acadiana Technical College American University of Health Sciences Adams State University* American University of Kuwait Adelphi University* American University of Puerto Rico Adler School of Professional Psychology American University of Sharjah Adrian College Amherst College* Adventist University of Health Sciences Amridge University, Inc. Agnes Scott College* An Cheim Computer Services Aims Community College Ancilla College Air Force Institute of Technology Anderson University Air University, USAF Andover College Alabama A&M University Andrew College Alabama Community College System Andrews University Alabama Southern Community College Angelo State University* Alabama State University Anglia Ruskin University Alamo Community College District Central Office* Anna Maria College Alaska Pacific University Anne Arundel Community College Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences of Anoka Technical College Union University Anoka-Ramsey Community College Albany State University Anoka-Ramsey Community College-Cambridge -

Curriculum Vitae Craig Gerald Bartholomew (Rev Prof.) January 2016

Curriculum Vitae Craig Gerald Bartholomew (Rev Prof.) January 2016. Born in South Africa British and South African Citizen, Permanent residence in Canada. Contact Information [email protected] Current Position H. Evan Runner Professor of Philosophy and Professor of Religion and Theology at Redeemer University College. (2004 - ) Adjunct faculty, Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College, Bristol (2009 - ) Herzl Institute Senior Fellow (2015- ) Previous Positions Ordained as deacon in 1986, ordained as priest in 1987. Pastoral minister in the Church of England in SA (1987-1989). Lecturer in Old Testament and Hebrew, George Whitefield College, Cape (1989-1992). Research assistant (post-doctoral position), Research Fellow and Senior Research Fellow in Theology and Religious Studies, School of Humanities, University of Gloucestershire, UK. (1996 – 2003) Visiting Professor in Scripture and Hermeneutics at Chester University, UK (2004 - 2007) Schooling and Sport Westville Boys High School 1974-1978 Matriculated in 1978 with A average. 1 Dux, 1978. Natal Junior Tennis and Natal Schools Tennis, 1978. Tertiary Education Diploma in Theology (1981) Bible Institute of SA, Cape. B.Th. (1982) University of South Africa (majors in OT and NT) M.A. (1984/1988) Oxford University. M.A. (1992) Potchefstroom University. (In Old Testament. Thesis title: The Composition of Deuteronomy. A Critical Analysis of the Approaches of E.W. Nicholson and A.D.H. Mayes.) Research in philosophy at the Institute for Christian Studies, Toronto. (1992-1993) Ph.D. (1997) Bristol University Doctoral research concerning the interrelationship of philosophy, literary theory and Old Testament hermeneutics, focused exegetically on readings of Ecclesiastes. Title: Reading Ecclesiastes: Old Testament Exegesis and Hermeneutical Theory. -

Revised November 30, 2010 CURRICULUM

Revised November 30, 2010 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: JEFFREY, David Lyle DATE OF BIRTH: 28 June, 1941 PLACE OF BIRTH: Ottawa, CANADA CITIZENSHIP: Canadian; US Permanent Resident (Green card.) FAMILY: Married to Katherine Beth Brown Children: Bruce, Kirstin, Adrienne, Gideon, Joshua CHURCH AFFILIATION: Attending Our Lady of the Lake Anglican, Laguna Park, Texas DEGREES Ph.D. English, Princeton University, 1968 B.A. English, Wheaton College, Illinois, 1965 POSITIONS HELD 1. Distinguished Professor of Literature and Humanities, Baylor University, 2000- Senior Vice Provost, 2001-2003 Interim Dean, Honors College, 2002-2003 Provost, 2003-2005 2. Professor Emeritus, Department of English, University of Ottawa, 1996-. 3. Guest Professor, Peking University, (Beijing, China), 1996- 4. Honorary Professor, University of International Business and Economics (Beijing, China), 2005- 5. Professor of Art History, Augustine College, 1997- 2000. 6. Professor and Chairman, Department of English, University of Ottawa, 1978-81; Professor, 1978-96. 7. Visiting Professor, Graduate School, University of Notre Dame, 1995; 2002. 8. Associate Professor and Chairman (1973-76), Department of English, University of Victoria, 1973-76; Professor, 1976-78. 9. Visiting Professor, Graduate Faculty of Theology, Regent College, University of British Columbia, Spring Term, 1976; also Summer Sessions, 1970 and 1973; Adjunct Professor, 1978-83. 10. Reckitt Visiting Professor of English Literature, University of Hull, England, 1971-72. 11. Assistant Professor (1969-73) then Associate Professor of English (1973), University of Rochester, New York. Director of Medieval House Center, 1972-73. 12. Assistant Professor of English, University of Victoria, 1968-69. MAJOR FIELDS OF PROFESSIONAL INTEREST 1. Medieval Studies (including History of the English Language); medieval Latin, Italian French and Middle English Literature. -

Curriculum Vitae for Stephanie Gray Connors

Curriculum Vitae for Stephanie Gray Connors EDUCATION 2008–2009 Certification, with Distinction, in Health Care Ethics, U.S. National Catholic Bioethics Center, Philadelphia, PA 1998–2002 Bachelor of Arts in Political Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC WORK EXPERIENCE 2014–Present President, Love Unleashes Life 2001–2014 Executive Director and Co-Founder, Canadian Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform BOOK PUBLICATIONS 2015 Love Unleashes Life: Abortion and the Art of Communicating Truth, Published by Life Cycle Books 2011 A Physician’s Guide to Discussing Abortion, Published by Life Cycle Books AWARDS 2018 Joe Borowski Award from Life’s Vision Manitoba 2018 St. Camillus de Lellis Award from the Catholic Physicians Guild of Vancouver 2016 Defender of Life Award from Students for Life of America 2012 Dombowsky Memorial Award from Saskatchewan Pro-Life Association AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Pro-life apologetics on the topics of abortion and assisted suicide Teaching effective dialogue skills Debates Christian-based motivational and inspirational presentations Speaker and media training FEATURE PRESENTATION 2017 Talks at Google: “Abortion: From Controversy to Civility” given at Google headquarters in Mountain View, CA OTHER PRESENTATIONS See next page. www.loveunleasheslife.com Page 2 of 14 DEBATES Date Opponent Location 2019 Mara Clarke, Maggy Krell, Gloria Alvarez, La Ciudad de las Ideas And Robyn Blumner (Puebla, MX) 2018–15 Dr. Malcolm Potts University of California, Berkeley Obstetrician and Professor (Berkeley, CA) 2018 Nadine Strossen University of Virginia Former ACLU President Charlottesville, VA 2018 Professor Scott Moss University of Colorado Law Professor Boulder, CO 2017 Dr. Jonathan Peeters Cornell University Philosophy Professor (Ithaca, NY) 2016 Dr. -

Institutions Eligible to Participate in the 2018 Core Data Service * 2018 CDS Participant

Institutions Eligible to Participate in the 2018 Core Data Service * 2018 CDS Participant A.T. Still University of Health Sciences* Alliant International University President's Office Aalto University Alliant International University-Los Angeles Aaniiih Nakoda College* Alliant International University-San Diego Abilene Christian University* Alliant International University-San Francisco ABO Akademi University Alma College* Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Alpena Community College Academy of Art University Alvernia University Acadia University Alverno College* Acadiana Technical College Alvin Community College Acadiana Technical College Amarillo College Adams State University* Amberton University Adelphi University Ambria College of Nursing Adler Graduate School American Academy of Acupuncture and Oriental Adler University Medicine Adrian College American Academy of Art Adtalem Global Education American Bible College and Seminary Advanced Training Associates American Business & Technology University Adventist University of Health Sciences American Career College Agnes Scott College* American College of Acupuncture & Oriental medicine AIB College of Business American College of Education Aims Community College* American College of Healthcare Sciences* Air University, USAF American Film Institute Alabama A&M University American Graduate University Alabama State University American Indian College of the Assemblies of God Alamo Community College District Central Office* American Institute of Alternative Medicine Alaska Bible College American -

A History of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies Page 1

A History of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies page 1 A History of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies John Macpherson A brief introduction (2017) Peter Richardson It is appropriate during the 2017 celebration of Canada’s Sesquicentennial to make available the 1 history of the Canadian Society of Biblical Studies published fifty years ago during Canada’s Centennial. 2 John Macpherson emphasized the organizational developments at that stage of CSBS’s progress; his approach was amplified fifteen years later during CSBS’s fiftieth anniversary in a much fuller publication: John S. Moir,3 A History of Biblical Studies in Canada: A Sense of Proportion (Chico CA: Scholars Press, 1982). Moir adopted a longer time frame, paid more attention to the Canadian context, and considered wider intellectual currents. Of four seminal figures in CSBS’s evolution, two were lionized in Macpherson’s history and two not. In 1933 the two persons giving CSBS life and shape were Sir Robert Falconer,4 then recently retired as President of the University of Toronto, and the younger R. B. Y. Scott,5 who ensured its ongoing stability. Forty years later, Norman E. Wagner6 and Robert C. Culley7 re-vitalized and re-focused the Society. It is no exaggeration that CSBS owes its original shape to Falconer and Scott, and its inherited energy to 1 As the Presidential address to CSBS in 1962 this history appeared in print in a revised form with other contributions in a mimeographed volume to celebrate Canada’s centennial: Norman E. Wagner, editor, Canadian Biblical Studies (1967). I have retyped it with minor alterations in punctuation (July 2017) and added the footnotes.