National Sports Policy Implementation and Nigeria's Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special-Sessions-1998-37941-600-21

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 6th INTERNATIONAL POST GRADUATE SEMINAR 1/5-12/6/1998 4th JOINT INTERNATIONAL SESSION FOR DIRECTORS OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMIES, MEMBERS AND STAFF OF NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES AND INTERNATIONAL SPORTS FEDERATIONS 7-14/5/1998 ANCIENT OLYMPIA ISBN: 960-8144-04-3 ISSN: 1108-6831 Published and edited by the International Olympic Academy. Scientific supervisor: Dr. Konstantinos Georgiadis/IOA Dean. Athens 2000 EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY President Nikos FILARETOS (I.O.C. Member) 1st Vice-President Sotiris YAGAS t 2nd Vice-President Georgios MOISSIDIS Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Member ex-officio Lambis NIKOLAOU (I.O.C. Member) Members Dimitris DIATHESSOPOULOS Georgios GEROLIMBOS Ioannis THEODORAKOPOULOS Epaminondas KIRIAZIS Cultural Consultant Panayiotis GRAVALOS Honorary President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH Honorary Vice-President Nikolaos YALOURIS 3 I.O.C. COMMISSION FOR THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY AND OLYMPIC EDUCATION President Nikos FILARETOS IOC Member in Greece Vice-President Carol Ann LETHEREN IOC Member in Canada Members Fernando Ferreira Lima BELLO IOC Member in Portugal Valeriy BORZOV IOC Member in Ukraine Ivan DIBOS IOC Member in Peru Francis NYANGWESO IOC Member in Uganda Mohamed ZERGUINI IOC Member in Algeria Representatives George MOISSIDIS Fern. BELTRANENA VALLARADES Rene ROCH Representative of IFs Dieter LANDSBERG-VELEN Representative of IFs Philippe RIBOUD Representative of Athletes Individual Members Helen BROWNLEE (Australia) Conrado DURANTEZ (Spain) Yoon-bang KWON (Korea) Marc MAES (Belgium) Prof. Norbert MUELLER (Germany) 4 PROLOGUE The publication of the proceedings of the IOA's special ses- sions, for the second consecutive year, is one more contribution of the Ephoria of the Academy and the Hellenic Olympic Com- mittee to Olympism and Olympic Education. -

Africathlète Août 2004

Partenaires Officiels de la CAA Official AAC Partners 2 • africathlete - août 2004 Sommaire Contents Edito Citius, altius, fortius Jeux olympiques d’Athènes 2004 Que brillent les “ Etoiles “ d’Afrique ! Athens 2004 : Let african’s stars shine at athens olympic games ! 14e Championnat d’Afrique à Brazzaville L’Afrique du Sud en force, les performances au rendez-vous 14th African Championship in Brazzaville Performances galore as Shouth Africans rule the roost 15e championnat d’Afrique Rendez-vous à Maurice en 2006 African senior championships See you in Mauririus 2006 Circuit Africain des meetings Un véritable coup d’éclat African meet circuit : Is a remarkable feat Championnats du monde Juniors Les promesses de la jeune sève World junio championships : Africa’s promising young talents La confejes et la CAA à l’air du temp Confejes and CAA keep up with progress août 2004 - africathlete • 3 Editorial Citius, altius, fortius ’Afrique qui gagne, c’est bel et bien l’athlétisme. Vainqueur des quatre dernières éditions de la L Par/by Hamad Kalkaba Malboum Coupe du monde des Confédérations, l’Afrique peut Président de la CAA / AAC President aussi exhiber avec fierté ses multiples champions du monde, détenteurs de records du monde et cham- pions olympiques. Aucune discipline sportive, sur le continent, ne peut encore étaler un pareil palmarès. Et Citius, altius, fortius cerise sur le gâteau, les deux meilleurs athlètes du monde en 2003, en l’occurrence la Sud-Africaine frica is winning through athletics. In addition to win- Hestrie Cloete et le Marocain Hicham El Guerrouj, Aning the last four editions of the Confederations sont des fils de l’Afrique. -

1F35e3e1-Thisday-Jul

NNPC Awards Oil Swap Contracts to 34 Firms Ejiofor Alike with agency contracts to exchange crude the deals said. Barbedos/Petrogas/Rainoil; referred to as offshore crude supplies crude oil to selected reports oil for imported fuel. The winning groups include: UTM/Levene/Matrix/Petra oil processing agreements local and international oil Under the new contract that BP/Aym Shafa; Vitol/Varo; Atlantic; TOTSA; Duke Oil; (OPAs) and crude-for-products traders and refineries in The Nigerian National will take effect this month, a Trafigura/AA Rano; MRS; Sahara; Gunvor/Maikifi; exchange arrangements, are exchange for petrol and diesel. Petroleum Corporation total of 15 groupings, with at Oando/Cepsa; Bono/ Litasco /Brittania-U; and now known as Direct Sale- NNPC had in May 2017, (NNPC) yesterday issued least 34 companies in total, Akleen/Amazon/Eterna; Mocoh/Mocoh Nigeria. Direct Purchase Agreements signed the deals with local award letters to oil firms received award letters, four Eyrie/Masters/Cassiva/ NNPC’s crude swap deals, (DSDP). for the highly sought-after sources with knowledge of Asean Group; Mercuria/ which were previously Under the deals, the NNPC Continued on page 8 Lower Commodity Prices Weaken Inflation to 11.22%... Page 8 Tuesday 16 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8863 Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO Oyo Governor Publicly Declares Assets Worth over N48bn... Page 9 Obasanjo Calls for National Confab, Says Nigeria is on the Precipice Writes Buhari PDP, Afenifere, Ohanaeze, Southern, Middle Belt leaders back former president Yakassai faults content of letter By Our Correspondents plunging into an abyss of before Nigeria witnesses the varied reactions from some aligned with Obasanjo’s Forum (ACF), Alhaji Tanko insecurity. -

AFRREV STECH, Vol

AFRREV STECH, Vol. 1 (2) April-July, 2012 AFRREV STECH An International Journal of Science and Technology Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Vol.1 (2) April-July, 2012:101-111 ISSN 2225-8612 (Print) ISSN 2227-5444 (Online) Sport as an Instrument for Social Cohesion in Nigeria Jeroh, Eruteyan Joseph, Ph.D. Department of Physical & Health Education, Delta State University, Abraka E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +2348038815809 Abstract The paper looked at the various roles sport could play in bringing about social cohesion in Nigeria. This was viewed from the perspective of benefits of sports to the society, schools, social significance of sports. The dark side of sport was also periscoped into. It was concluded that sport can provide opportunities to co-operate with others to achieve goals, make friends and straighten relationships with others, etc. It was recommended that governments from federal to local should encourage mass participation in sports by providing sports infrastructures nationwide. Physical and sport education should be mandatory at all levels of education. 101 Copyright © IAARR 2012: www.afrrevjo.net/stech AFRREV STECH, Vol. 1 (2) April-July, 2012 Key words: Meritocratric, Federal character, Chauvinists, Social transformation, Over-aged, Role Learning. Introduction From the onset, it might seem unnecessary defining sport because through experience and intuition most people already know what the word means. For the purpose of this discourse there is the need to know the meaning of sport as seen by many scholars. Loy (1978) claimed that sport must have five characteristics. It must: a) be play like in nature; b) involve some element of competition; c) be based on physical prowess; d) involve elements of skill, strategy, and chance; and e) have an uncertain outcome. -

Detailed List of Performances in the Six Selected Events

Detailed list of performances in the six selected events 100 metres women 100 metres men 400 metres women 400 metres men Result Result Result Result Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country (sec) (sec) (sec) (sec) 1928 Elizabeth Robinson USA 12.2 1896 Tom Burke USA 12.0 1964 Betty Cuthbert AUS 52.0 1896 Tom Burke USA 54.2 Stanislawa 1900 Frank Jarvis USA 11.0 1968 Colette Besson FRA 52.0 1900 Maxey Long USA 49.4 1932 POL 11.9 Walasiewicz 1904 Archie Hahn USA 11.0 1972 Monika Zehrt GDR 51.08 1904 Harry Hillman USA 49.2 1936 Helen Stephens USA 11.5 1906 Archie Hahn USA 11.2 1976 Irena Szewinska POL 49.29 1908 Wyndham Halswelle GBR 50.0 Fanny Blankers- 1908 Reggie Walker SAF 10.8 1980 Marita Koch GDR 48.88 1912 Charles Reidpath USA 48.2 1948 NED 11.9 Koen 1912 Ralph Craig USA 10.8 Valerie Brisco- 1920 Bevil Rudd SAF 49.6 1984 USA 48.83 1952 Marjorie Jackson AUS 11.5 Hooks 1920 Charles Paddock USA 10.8 1924 Eric Liddell GBR 47.6 1956 Betty Cuthbert AUS 11.5 1988 Olga Bryzgina URS 48.65 1924 Harold Abrahams GBR 10.6 1928 Raymond Barbuti USA 47.8 1960 Wilma Rudolph USA 11.0 1992 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.83 1928 Percy Williams CAN 10.8 1932 Bill Carr USA 46.2 1964 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.4 1996 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.25 1932 Eddie Tolan USA 10.3 1936 Archie Williams USA 46.5 1968 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.0 2000 Cathy Freeman AUS 49.11 1936 Jesse Owens USA 10.3 1948 Arthur Wint JAM 46.2 1972 Renate Stecher GDR 11.07 Tonique Williams- 1948 Harrison Dillard USA 10.3 1952 George Rhoden JAM 45.9 2004 BAH 49.41 1976 -

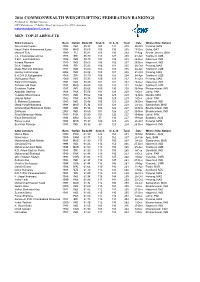

2018 Commonwealth Rankings

2018 COMMONWEALTH WEIGHTLIFTING FEDERATION RANKINGS Produced by: Michael Noonan CWF Statistician, 47 Saltley Street, Spotswood Vic 3015, Australia [email protected] MEN: TOP-25 ABSOLUTE as at 01 July 56kg Category Born Nation Body.Wt Snatch Cl & Jk Total Date Where (City, Nation) Hazal Wafie Muhammad Azroy 1994 MAS 55.88 117 144 261 5-Apr Gold Coast, AUS Jeremy Lalrinnunga 2002 IND 55.85 114 136 250 24-Apr Urgench, UZB Guru Raja 1992 IND 55.94 111 138 249 5-Apr Gold Coast, AUS J.A. Chaturanga Lakmal 1988 SRI 55.97 114 134 248 5-Apr Gold Coast, AUS Korada Ramana 1989 IND 55.90 108 132 240 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND Manueli Tulo 1990 FIJ 56.00 105 135 240 24-Feb Suva, FIJ M. Manoj Kumar 1995 IND 55.80 105 132 237 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND S. Ramkumar 1994 IND 55.80 105 131 236 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND Abdullah Ghafoor 1986 PAK 56.00 105 130 235 11-Jan Gujranwala, PAK Ch. Rishikanta Singh 1998 IND 56.00 105 130 235 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND Piyush Singh 1999 IND 55.60 102 131 233 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND S. Sidhanta Gogoi 2004 IND 101 130 231 5-Feb New Delhi, IND Shubham Kolekar 1999 IND 100 130 230 21-Feb Visakhapatnam, IND Elson Brechtefeld 1994 NRU 55.87 100 130 230 5-Apr Gold Coast, AUS Zakhuma 2001 IND 101 125 226 21-Feb Visakhapatnam, IND V. Chinnam Naidu 1997 IND 55.70 99 125 224 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND Ahmed Mahmood Akhter 1993 PAK 55.80 105 115 220 11-Jan Gujranwala, PAK Selvam 1991 IND 55.10 100 120 220 21-Jan Moodbidri, IND Muna Nayak 2002 IND 95 121 216 21-Feb Visakhapatnam, IND Youri Simard 2001 CAN 55.40 98 115 213 20-Jan Halifax, CAN Markio Tario 2004 IND 93 120 213 5-Feb New Delhi, IND Muhammad Yousaf 2001 PAK 54.62 93 120 213 16-Apr Lahore, PAK Ganesh R. -

OCHA in 2012 13 Temp Cover.Pdf

Credits OCHA wishes to acknowledge the contributions of its committed staff at headquarters and in the field in preparing this document. Managing Editor: Tomas de Mul Copy Editor: Nina Doyle Collaborative Content: Strategic Planning Unit Cover, Maps and Graphics: Advocacy and Visual Media Unit Design and Layout: raven + crow studio Printing: United Nations Department of Public Information Cover Photos: © UNICEF/Shehzad Noorani © OCHA/David Ohana © UNHCR/S. Modola © UNHCR / F.NOY For additional information, please contact: Donor Relations Section Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 917 1690 OCHA in 2012 & 2013 PLAN AND BUDGET This is a summary of OCHA’s Plan and Budget for 2012 and 2013. For more details on the organization’s planned activities and accompanying budget, please visit: www.unocha.org/ocha2012-13 The website provides comprehensive OCHA-wide strategies, full country office and regional office plans and performance indicators, and detailed budget and staffing information. TABLE OF CONTENTS A child rests inside an evacuation site in Maguindanao, Philippines. © IRIN/Veejay Villafranca Foreword ....................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ...................................................................................................................... 2 Strategic Plan ............................................................................................................... -

Start List Package

Start List Package Weightlifting Contents 1. C58 Timetable 2. C35 Technical Officials 3. C30 Number of Entries by CGA 4. C24 Records 5. C51 Start List Men's 56kg Women's 48kg Men's 62kg Women's 53kg Men's 69kg Women's 58kg Men's 77kg Women's 63kg Men's 85kg Women's 69kg Men's 94kg Women's 75kg Men's 105kg Women's +90kg Women's 90kg Men's +105kg Carrara Sports Arena 1 Weightlifting Timetable As of TUE 3 APR 2018 at 15:15 G r o u p s o f O f f i c i a l s Start Gender Cat. Date Athletes Chief Tech. Time TD Jury Referee Marshal Timekeeper Contrl. Secr. Doctor 1 Men 56 THU 5 APR 09:30 12 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 Women 48 THU 5 APR 14:00 11 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 3 Men 62 THU 5 APR 18:30 15 1 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 4 Women 53 FRI 6 APR 09:30 14 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 5 Men 69 FRI 6 APR 14:00 14 1 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 6 Women 58 FRI 6 APR 18:30 15 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 Men 77 SAT 7 APR 09:30 14 1 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 8 Women 63 SAT 7 APR 14:00 13 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 9 Men 85 SAT 7 APR 18:30 15 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 10 Women 69 SUN 8 APR 09:30 13 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 2 11 Men 94 SUN 8 APR 14:00 15 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 12 Women 75 SUN 8 APR 18:30 12 1 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 13 Men 105 MON 9 APR 09:30 14 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 14 Women 90 MON 9 APR 14:00 8 1 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 15 Women +90 MON 9 APR 14:00 8 1 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 16 Men +105 MON 9 APR 18:30 13 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 2 NOTES Typical duration of a Group session with 12 athletes is approximately two hours. -

Wsn 156 (2021) 119-129 Eissn 2392-2192

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 156 (2021) 119-129 EISSN 2392-2192 Sports as an Instrument of Foreign Policy Pursuit: A Case of Nigeria Vincent Eseoghene Efebeh Department of Political Science, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Over the years, sports have been used in the global world to integrate people of various cultures and have also been used as a unifying force to connect culturally diverse people. Sports, on the other hand, have also been used to drive the economic interests of state actors, since investments in the sports industry are worth billions of U.S. dollars. The size of the contemporary sports arena makes it a priority for state actors to use the instruments of foreign policy to promote their national interests. This paper therefore explores the sport and how it was used by state actors as a weapon to achieve their foreign policy objectives. The paper relied on a qualitative knowledge gauging process. The paper shows that the sporting arena is also a real space for the interplay of state interests. The paper advises that the condition of Nigeria needs to Keywords: Foreign Policy, Sports, Physical education, Nigeria 1. INTRODUCTION Globally, a foreign relation is dependent on many entities since states will continue to compete to attain recognition and influence by indisputable act of accomplishing something. Given the objective of the United Nations to preserve better international ties, stability and protection, nations are now taking on a certain shape, attributing policies, tactics or preparing fair ways to peacefully legitimize their dominance and the use of sports as an instrument of the ( Received 17 March 2021; Accepted 03 April 2021; Date of Publication 04 April 2021 ) World Scientific News 156 (2021) 119-129 pursuit of foreign policy by most countries. -

Africathlète Juillet 2004

Partenaires Officiels de la CAA Official AAC Partners 2 • africathlete - juillet 2004 Sommaire Contents Editorial «Notre vision pour l’athlétisme africain» Editorial “Our vision for African athletics” 4 18e Congrès de la CAA : Les pistesdu 3e millénaire 18th AAC Congress : Charting the 3rd millennium 5-9 Lamine Diack passe le témoin à Hamad Kalkaba Lamine Diack hands over to Hamad Kalkaba 10 L’Afrique lance un circuit de 11 meetings Africa launches 11 meet circuit 11 Bienvenue à Brazzaville Welcome to Brazzaville 12 Calendrier Program 13-15 1ère rencontre Afrique-Europe en Septembre 2005 à Tanger Tangiers to host 1st Euro-African meet in September 2005 16 Les entraîneurs Africains dévoilent leurs ambitions African coaches reveal their ambitions 17 La CONFEJES soutient le CIAD CONFEJES supports CIAD 18 L’Afrique aux mondiaux de Paris : Mieux qu’à Edmonton World championships : Africa did better at Paris than at Edmonton 19-20 L’Afrique à la Coupe du monde : Le triomphe de l’esprit d’équipe Africa at the World Cup : A victory for team spirit 21-23 Etoiles d’Afrique Stars of Africa 24 Maria Mutola : Reine de la Golden League Maria Mutola : Queen of Golden League 25 Kenenisa Bekele détrône Gebrselassié Kenenisa Bekele supplants Gebrselassié 26 Records d’Afrique - Hommes Men Area Records - Africa 27 Records d’Afrique - Dames Women Area Records - Africa 28 Records du Monde - Hommes Men World Records 29 Records du Monde - Dames Women World Records 30 juillet 2004 - africathlete • 3 Editorial «Notre vision pour l’athlétisme africain» «Faire de l’athlétisme le sport le plus populaire, capable de promouvoir au sein de la jeunesse africaine les valeurs de solidarité et de performance, lui Par/by Hamad Kalkaba Malboum permettant de participer efficacement aux efforts de Président de la CAA / AAC President développement du continent», telle est notre vision pour l’athlétisme africain. -

2016 Commonwealth Weightlifting Federation

2016 COMMONWEALTH WEIGHTLIFTING FEDERATION RANKINGS Produced by: Michael Noonan CWF Statistician, 47 Saltley Street, Spotswood Vic 3015, Australia [email protected] MEN: TOP-25 ABSOLUTE 56kg Category Born Nation Body.Wt Snatch Cl & Jk Total Date Where (City, Nation) Guru Raja Poojary 1992 IND 55.98 108 141 249 26-Oct Penang, MAS Hazal Wafie Muhammad Azroy 1994 MAS 55.65 109 136 245 13-Dec Doha, QAT Manueli Tulo 1990 FIJ 55.81 106 136 242 7-Aug Rio de Janeiro, BRA J.A. Chaturanga Lakmal 1988 SRI 55.70 113 127 240 24-Apr Tashkent, UZB T.B.C. Lalchhanhima 1992 IND 55.79 103 135 238 26-Dec Nagercoil, IND Korada Ramana 1989 IND 55.66 105 132 237 26-Dec Nagercoil, IND D.I.K. Yodage 1996 SRI 55.46 104 131 235 26-Oct Penang, MAS Dipak Ramesh Mahajan 1991 IND 55.80 106 129 235 24-Apr Tashkent, UZB Jeremy Lalrinnunga 2002 IND 55.84 108 127 235 21-Oct Penang, MAS E.A.D.K.D. Edogawatte 1988 SRI 55.70 106 128 234 24-Apr Tashkent, UZB Muthupandi Raja 2000 IND 55.93 100 133 233 21-Oct Penang, MAS Ranjit Chinchwade 1991 IND 55.49 101 131 232 26-Dec Nagercoil, IND Zulhelmi Md Pisol 1993 MAS 55.85 103 128 231 24-Apr Tashkent, UZB Shubham Todkar 1997 IND 55.66 100 130 230 30-Nov Bhubaneswar, IND Abdullah Ghafoor 1986 PAK 55.56 101 128 229 8-Dec Lahor, PAK Yeadula Shiva Kumar 1989 IND 55.62 104 125 229 14-Nov Merida, MEX Usman Akbar 1982 PAK 55.78 104 125 229 8-Dec Lahor, PAK S. -

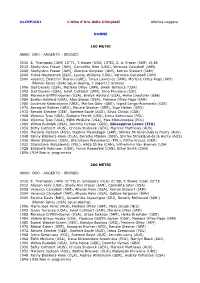

Argento - Bronzo

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera DONNE 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. Thompson (JAM) 10”71, T. Bowie (USA) 10”83, S. A. Fraser (JAM) 10,86 2012 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Carmelita Jeter (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2008 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Sherone Simpson (JAM), Kerron Stewart (JAM) 2004 Yuliva Nesterenko (BLR), Lauryn Williams (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2000 vacante, Ekaterini Thanou (GRE), Tanya Lawrence (JAM), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) (Marion Jones (USA) squal.doping, 2 argenti 1 bronzo) 1996 Gail Devers (USA), Merlene Ottey (JAM), Gwen Torrence (USA) 1992 Gail Devers (USA), Juliet Cuthbert (JAM), Irina Privalova (CSI) 1988 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA), Evelyn Ashford (USA), Heike Drechsler (GEE) 1984 Evelyn Ashford (USA), Alice Brown (USA), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (URS), Marlies Göhr (GEE), Ingrid Lange-Auerswald (GEE) 1976 Annegret Richter (GEO), Renate Stecher (GEE), Inge Helten (GEO) 1972 Renate Stecher (GEE), Raelene Boyle (AUS), Silvia Chivás (CUB) 1968 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Barbara Ferrell (USA), Irena Szewinska (POL) 1964 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Edith McGuire (USA), Ewa Klobukowska (POL) 1960 Wilma Rudolph (USA), Dorothy Hyman (GBR), Giuseppina Leone (ITA) 1956 Betty Cuthbert (AUS), Christa Stubnick (GER), Marlene Matthews (AUS) 1952 Marjorie Jackson (AUS), Daphne Hasenjäger (SAF), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen (OLA), Dorothy Manley (GBR), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1936 Helen Stephens (USA), Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Käthe Krauss (GER) 1932 Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Hilda Strike (CAN), Wilhelmina Van Bremen (USA 1928 Elizabeth Robinson (USA), Fanny Rosenfeld (CAN), Ethel Smith (CAN) 1896-1924 Non in programma 200 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E.