DRAFTING the TREATY of ACCESSION § 1. Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of European Union Accession in Democratisation Processes

The role of European Union accession in democratisation processes Published by Democratic Progress Institute 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] +44 (0)203 206 9939 First published, 2016 DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable 2 The role of European Union accession in democratisation processes Contents Foreword: ...................................................................................5 Abbreviations: ............................................................................7 Introduction: ..............................................................................8 I. European Union accession and democratisation – An overview .............................................................................11 A) Enlargement for democracy – history of European integration before 1993 ........................................................11 • Declaration on democracy, April 1978, European Council: .........................................................12 B) Pre accession criteria since 1993 and the procedure of adhesion ..........................................................................15 -

From Points of View of Monetary Integration Maturity) 1

THE EURO AND CENTRAL EUROPE (FROM POINTS OF VIEW OF MONETARY INTEGRATION MATURITY) 1 TIBOR PALANKAI1 1Emeritus Professor of Corvinus University of Budapest E-mail:[email protected] The paper discusses the frameworks and development of the introduction of the Euro in Central Europe, with a focus on pre-entry countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Croatia). The main elements of monetary integration maturity are the state of real-integration (possibilities of large saving in transaction costs), meeting the criteria of functioning market economy and the single market; macro-economic stability and meeting the Maastricht criteria; and shortcomings of absorption (integration) capacities of the EU. Controversial questions are also discussed, such as requirements concerning inflation, the budget deficit or exchange rate stability. The paper argues that the countries under scrutiny show diverging courses of action and policies, public support is also unclear, and the interests of TNCs and political elites contradict each other. Cultural, legal, security or emotional factors will pay a key role in eventual adoption, and prospects also depend on the solution of the current debt and migration crises. Keywords: Euro and Central Europe, monetary maturity, diverging interests, attitudes, policies, and prospects. JEL-codes: F2, F3 1. FRAMEWORK OF MONETARY INTEGRATION FOR THE CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN NEW MEMBERS The full EU membership of CEE countries assumes their full EMU participation. This corresponds to the Copenhagen accession criteria, namely they should have the “ability to take on the obligations of membership, including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union”. They have no possibility of opting out, like the United Kingdom and Denmark. -

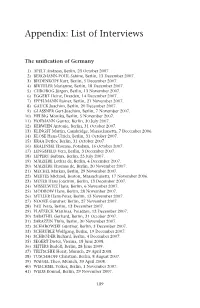

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Death of an Institution: the End for Western European Union, a Future

DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? EGMONT PAPER 46 DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? ALYSON JK BAILES AND GRAHAM MESSERVY-WHITING May 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1785 7 D/2011/4804/136 U 1612 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. -

The EU's Normative Power

The EU’s Normative Power – Its Greatest Strength or its Greatest Weakness? By Tornike Metreveli The Starting Point The growing influence of the European Union (EU) on the international political arena and at the same time its “particular kind” of characteristics as an international player appears to be a widely debated issue among various scholars of social sciences over the last decades. During this period a wide range of theories and concepts have attributed various epithets to the EU and tried to explain its power in different, sometimes controversial ways. Consequently the descriptions of the EU in international relations vary from it being a “Kantian paradise” (Kagan, 2004), a “vanishing mediator” (Manners, 2006:.174) to “an economic giant, a political dwarf, and a military worm” (Eyskens, 1991). For some scholars the concept of the EU goes beyond the bold epithets and is analyzed from the critical-social theoretical perspective, where the latter was hypothesized as an actor that spread its own norms beyond its borders and whose power lies in its system of values and forms of relations with the outer world (Manners, 2002). Having said this, the article tries to focus on this theoretical approach while addressing this “unique political animal” (Piris, 2010: 337). Thus, the concept pioneered by Ian Manners, particularly the idea of Europe’s “normative power” (NPE hereafter), is the central point of departure of this paper; and the critical analysis of its greatest strengths and weaknesses is the article’s main objective. Divided in three parts, the paper firstly focuses on the conceptual analysis of the NPE, and its definitions. -

European Union Candidate Countries: 2003 Referenda Results

Order Code RS21624 September 26, 2003 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web European Union Candidate Countries: 2003 Referenda Results name redacted Specialist in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia held public referenda from March through September 2003 on becoming members of the European Union (EU). These nine countries plus Cyprus are expected to accede to the EU in May 2004, bringing the EU’s total membership to twenty-five. This report briefly analyzes the referenda results and implications. It will not be updated. For additional information see CRS Report RS21344, European Union Enlargement. Background to the Referenda The European Union is embarking on a major enlargement process that will expand the Union from fifteen to twenty-five members by mid-2004, and potentially more in the coming years. The current round of enlargement is notable for its size (which will expand the EU zone from 378 to over 450 million people) and inclusion of many former Communist bloc countries. Ten candidate countries – Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia – concluded accession negotiations in December 2002 and signed the Treaty of Accession on April 16, 2003 in Athens. Bulgaria and Romania aim to join the EU by 2007. Turkey is recognized as an EU candidate, and the countries of the western Balkans also seek eventual EU membership, although no target entry date has been identified for these states. From March through September 2003, nine of the ten acceding countries held public referenda on joining the EU according to their own constitutional procedures (Cyprus did not hold a referendum but ratified the accession treaty through a parliamentary vote). -

The Recognition of Diplomas and the Free Movement of Professionals in the European Union: Fifty Years of Experiences

The Recognition of Diplomas and the Free Movement of Professionals in the European Union: Fifty Years of Experiences HILDEGARD SCHNEIDER SJOERD CLAESSENS MAASTRICHT UNIVERSITY 1. INTRODUCTION This year we celebrate in Europe the 50th anniversary of the entering into force of the Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community. After half a century of European integration it is an appropriate moment to look back on the achievements realized in this period. This paper wants to address specifically the issues of professional mobility, qualification recognition and the developments towards a European Space of Education. Special attention will be given to the increasing international mobility of the legal profession and the consequences of this development for the legal education on academic as well as professional level in the Member States of the European Union. One of the main goals of the E(E)C Treaty from its very beginning has been the creation a common market for all economic activities. This includes the free movement of professionals. National rules which had the effect of preventing persons from providing cross border professional services or establishing themselves in another Member State had to be progressively abolished. Barriers to mobility, such as the requirement of a national diploma or language requirements, can as much constitute obstacles to the completion of the internal market as e.g. the use of different safety standards for technical goods. As there is no common educational system in Europe and the routes to professional and trade activities vary significantly between the Member States these differences can cause serious barriers to the free movement of persons. -

Steps to European Unity Community Progress to Date: a Chronology This Publication Also Appears in the Following Languages

Steps to European unity Community progress to date: a chronology This publication also appears in the following languages: ES ISBN 92-825-7342-7 Etapas de Europa DA ISBN 92-825-7343-5 Europa undervejs DE ISBN 92-825-7344-3 Etappen nach Europa GR ISBN 92-825-7345-1 . '1;1 :rtOQEta P'J~ EiiQW:rtTJ~ FR ISBN 92-825-7347-8 Etapes europeennes IT ISBN 92-825-7348-6 Destinazione Europa NL ISBN 92-825-7349-4 Europa stap voor stap PT ISBN 92-825-7350-8 A Europa passo a passo Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987 ISBN 92-825-7346-X Catalogue number: CB-48-87-606-EN-C Reproduction authorized in whole or in pan, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in the FR of Germany Contents 7 Introduction 9 First hopes, first failures (1950-1954) 15 Birth of the Common Market (1955-1962) 25 Two steps forward, one step back (1963-1965) 31 A compromise settlement and new beginnings (1966-1968) 35 Consolidation (1968-1970) 41 Enlargement and monetary problems (1970-1973) 47 The energy crisis and the beginning of the economic crisis (1973-1974) 53 Further enlargement and direct elections (1975-1979) 67 A Community of Ten (1981) 83 A Community of Twelve (1986) Annexes 87 Main agreements between the European Community and the rest of the world 90 Index of main developments 92 Key dates 93 Further reading Introduction Every day the European Community organizes meetings of parliamentar ians, ambassadors, industrialists, workers, managers, ministers, consumers, people from all walks of life, working for a common response to problems that for a long time now have transcended national frontiers. -

The Treaty of Accession and Differentiation in the Eu

Jurisprudencija, 2005, t. 72(64); 117–123 THE TREATY OF ACCESSION AND DIFFERENTIATION IN THE EU Academic Assistant Peter Van Elsuwege European Institute – Ghent University Pateikta 2005 m. geguės 2 d. Parengta spausdinti 2005 m. rugsėjo 20 d. Keywords: EU enlargement, Accession Treaty, transitional arrangements, safeguard clauses, Eurozone, Schengen area. Introduction With the entering into force of the Accession Treaty, on 1 May 2004, the process of European integration has entered a new phase. The EU of 25 will differ from the EU 15 in many ways. First, the accession of 10 new Member States has fundamentally changed the institutional framework and decision-making capacity of the Union. Reaching agreement with 25 Member States is obviously much more difficult than with 15. It remains to be seen how the Nice arrangement for QMV will affect the EU’s decision-making in practice awaiting the entry into force of the Constitution. Second, EU enlargement raises the question of balance in the EU. On the one hand, there is a question of balance between Member States: big and small, old and new, countries defending a more intergovernmental and supranational view on European integration. On the other hand, there is the traditional issue of balance between the institutions and in particular the institutional triangle constituted by the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament. The discussions surrounding the inauguration of the Barroso Commission clearly revealed the importance of this institutional balance and the power relations between the institutions. Third, and this is the central topic of today’s conference, EU enlargement raises questions about the future functioning of the Union and the application of the acquis communautaire. -

Guidelines Approximation with Eu

Funded by Implemented by a Consortium led by the European Union GFA Consulting Group GUIDELINES FOR UKRAINIAN GOVERNMENTAL ADMINISTRATION ON APPROXIMATION WITH EU LAW Алан Делькамп, експерт Як підвищити ефективність парламентських комітетів? Приклади передового міжнародного досвіду Вступ Комітети є найважливішими робочими органами у парламенті. Це не означає, що публічні засідання є менш важливими, але їхня функція відрізняється: публічно GUIDELINESобговорювати рішення та приймати остаточні рішення у церемоніальний спосіб. Це не означає, що парламентські комітети не відіграють політичну роль, але їхня робота відбувається на попередньому етапі, за винятком деяких конкретних обставин (законодавчі ініціативи комітету, якщо це конституційно можливо, або деякі особливі аспекти, такі як парламентські запити чи контрольні повноваження). FOR UKRAINIAN GOVERNMENTALНасправді, історично створення комітетів стало прагматичною відповіддю на очевидну потребу: зібрати депутатів парламенту в менші групи для забезпечення більш ефективної роботи. Вони також дають парламенту більше часу для підготовки своїх відповідей на урядові ініціативи. Створення комітетів є загальною тенденцією в парламентах, незалежно від того, яка може бути політична система (їх можна знайти в президентських, парламентських чи ADMINISTRATION будь-яких інших системах) і завжди є прагматичним ON (способи їхнього заснування були різні внаслідок різного історичного досвіду). Вони з'явилися в найрозвинутіших демократіях на початку 19-го століття (а часом і раніше1) і були закріплені сторіччя по тому в різних формах і на різних рівнях ієрархії норм (у регламенті чи навіть у конституції). Тим не менш, «мати» парламентської демократії, Англія, завжди мала застереження щодо розвитку повноважень комітетів. Вважалося, що підготовчі роботи APPROXIMATION1 Наприклад, можна знайти спеціальні комітети в англійському парламенті з кінця XVI століття, а також у французьких Генеральних штатах (але на відміну від англійського парламенту вони не були постійною установою у Франції). -

Treaty of Amsterdam Amending the Treaty on European Union, the Treaties Establishing the European Communities and Certain Related Acts

10 . 11 . 97 I EN | Official Journal of the European Communities C 340/ 1 TREATY OF AMSTERDAM AMENDING THE TREATY ON EUROPEAN UNION, THE TREATIES ESTABLISHING THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES AND CERTAIN RELATED ACTS (97/C 340/01 ) 10 . 11 . 97 1 EN I Official Journal of the European Communities C 340/ 3 HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF THE BELGIANS , HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN OF DENMARK, THE PRESIDENT OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, THE PRESIDENT OF THE HELLENIC REPUBLIC, HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF SPAIN, THE PRESIDENT OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC , THE COMMISSION AUTHORISED BY ARTICLE 14 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF IRELAND TO EXERCISE AND PERFORM THE POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE PRESIDENT OF IRELAND , THE PRESIDENT OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC , HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE GRAND DUKE OF LUXEMBOURG , HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN OF THE NETHERLANDS, THE FEDERAL PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, THE PRESIDENT OF THE PORTUGUESE REPUBLIC , THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FINLAND , HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF SWEDEN, HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND , HAVE RESOLVED to amend the Treaty on European Union , the Treaties establishing the European Communities and certain related acts , and to this end have designated as their Plenipotentiaries : C 340/4 | EN 1 Official Journal of the European Communities 10 . 11 . 97 HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF THE BELGIANS : Mr . Erik DERYCKE, Minister for Foreign Affairs ; HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN OF DENMARK : Mr . Niels Helveg PETERSEN , Minister for Foreign Affairs ; THE PRESIDENT OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY : Dr. Klaus KINKEL, Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs and Deputy Federal Chancellor ; THE PRESIDENT OF THE HELLENIC REPUBLIC : Mr . -

The Creeping Nationalisation of the EU Enlargement Policy Christophe Hillion

2010:6 Christophe Hillion The Creeping Nationalisation of the EU Enlargement Policy Christophe Hillion The Creeping Nationalisation of the EU Enlargement Policy – SIEPS 2010:6 – Report No. 6 November 2010 Publisher: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies The report is available at www.sieps.se The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and are not necessarily shared by SIEPS. Cover: Svensk Information AB Print: EO Grafiska AB Stockholm, November 2010 ISSN 1651-8942 ISBN 978-91-86107-21-5 PREFACE Often presented as the ‘most successful EU foreign policy’, enlargement has been one of the most important undertakings of the European Union over the last two decades. However, the experience of the Union’s admis- sion of several central and eastern European states has led to growing scepticism about further expansion. This timely report examines the recent adjustments made to address some of the policy’s shortcomings. It shows that the EU response has, on the whole, taken the form of a reaffirmation of the Member States’ control, both in the implementation of the policy, and through a reinforcement of their ‘constitutional requirements’ for accepting the admission of new Member States to the Union. What the author characterises as the ‘creeping nationalisation’ of enlar- gement strikes at the credibility, and thus the efficiency of the Union’s overall policy. It is also argued that it may raise questions about its com- patibility with the admission rules and general Union objectives, set out by the Treaty on European Union. By issuing this report, SIEPS hopes to make a contribution to the on-going debate on the future EU enlargement, and on the role of the Union as in- ternational actor.