Packaging Phoney Intellectual Property Claims (2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project SUN: a Study of the Illicit Cigarette Market In

Project SUN A study of the illicit cigarette market in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland 2017 Results Executive Summary kpmg.com/uk Important notice • This presentation of Project SUN key findings (the ‘Report’) has been prepared by KPMG LLP the UK member firm (“KPMG”) for the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), described in this Important Notice and in this Report as ‘the Beneficiary’, on the basis set out in a private contract dated 27 April 2018 agreed separately by KPMG LLP with the Beneficiary (the ‘Contract’). • Included in the report are a number of insight boxes which are written by RUSI, as well as insights included in the text. The fieldwork and analysis undertaken and views expressed in these boxes are RUSI’s views alone and not part of KPMG’s analysis. These appear in the Foreword on page 5, the Executive Summary on page 6, on pages 11, 12, 13 and 16. • Nothing in this Report constitutes legal advice. Information sources, the scope of our work, and scope and source limitations, are set out in the Appendices to this Report. The scope of our review of the contraband and counterfeit segments of the tobacco market within the 28 EU Member States, Switzerland and Norway was fixed by agreement with the Beneficiary and is set out in the Appendices. • We have satisfied ourselves, so far as possible, that the information presented in this Report is consistent with our information sources but we have not sought to establish the reliability of the information sources by reference to other evidence. -

2021 01 GSF Website Version and Format.Xlsx

Responsible Investment: Exclusions as at January 2021 This is a list of the companies whose securities the Government Superannuation Fund Authority has decided will not be held by the Government Superannuation Fund. This exclusions list is periodically reviewed and updated, and is provided for general information purposes only and not intended for any other purpose. Cluster Munitions Anhui Great Wall Military Industry Co Ltd ARYT INDUSTRIES LTD. ASHOT ‐ ASHKELON INDUSTRIES LTD. Bharat Dynamics Ltd HANWHA CORP LIG Nex1 Co., Ltd. POONGSAN CORPORATION Anti‐Personnel Mines Northrop Grumman National Presto Industries, INC Nuclear Explosive Devices and Nuclear Base Operators AECOM BWX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. CNIM Group SA FLUOR CORPORATION GENERAL DYNAMICS CORPORATION HONEYWELL INTERNATIONAL INC. HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES, INC. JACOBS ENGINEERING GROUP INC. LEIDOS HOLDINGS, INC. Leidos, Inc. LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION NORTHROP GRUMMAN INNOVATION SYSTEMS, INC. NORTHROP GRUMMAN SYSTEMS CORPORATION SERCO GROUP PLC URS Corp Tobacco 22ND CENTURY GROUP, INC. A‐1 Group Inc AL‐EQBAL INVESTMENT COMPANY PLC Altria Group Inc Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. B.A.T CAPITAL CORPORATION B.A.T. INTERNATIONAL FINANCE P.L.C. B.A.T. Netherlands Finance B.V. BADECO ADRIA d.d. Sarajevo Bang Holdings Corp Bellatora Inc Tobacco continued Bots Inc BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO (MALAYSIA) BERHAD BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO BANGLADESH CO. LTD. British American Tobacco Holdings (The Netherlands) B.V. British American Tobacco Kenya plc BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. British American Tobacco Uganda British American Tobacco Vranje a.d. Vranje British American Tobacco Zambia PLC British American Tobacco Zimbabwe (Holdings) Ltd Bulgartabac holding AD Carreras Ltd Cerealcom SA Alexandria CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC China Boton Group Company Limited Coka Duvanska Industrija ad Coka CONG TY CO PHAN NGAN SON CTO Public Company Ltd Duvanska industrija ad Bujanovac Eastern Company SAE ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES INTERNATIONAL GROUP, LTD. -

Iowa Directory of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers and Brands PLEASE NOTE Flavored Cigarettes & RYO Are Now Illegal

Iowa Directory of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers and Brands PLEASE NOTE Flavored Cigarettes & RYO are now illegal. Regardless of being on this List. See footnote *(3) 8/12/20 Iowa Additions to the Directory (within the last six months) PM Philip Morris USA Nat's cigarettes 8/12/20 PM Liggett Group Inc. Montego cigarettes 6/8/20 Deletions to the Directory (within the last six months) PM Sherman 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. Nat's cigarettes 8/12/20 PM Japan Tobacco International Wings cigarettes 5/7/20 PM King Maker Marketing Ace cigarettes 5/7/20 PM King Maker Marketing Gold Crest cigarettes 5/7/20 PM Kretek International Dreams cigarettes 5/7/20 Type of Manufacturer is for Participating (PM) or Non-Participating (NPM) with the Master Settlement Agreement. TYPE MANUFACTURER BRAND PRODUCT DATE NPM Cheyenne International, LLC Aura cigarettes 8/4/10 NPM Cheyenne International, LLC Cheyenne cigarettes 2/1/05 NPM Cheyenne International, LLC Decade cigarettes 2/1/05 PM Commonwealth Brands Inc Crowns cigarettes 5/31/11 PM Commonwealth Brands Inc Montclair cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Commonwealth Brands Inc Sonoma cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Commonwealth Brands Inc USA Gold cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Farmers Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. Baron American Blend cigarettes 9/20/05 PM Farmers Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. Kentucky's Best cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Farmers Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. Kentucky's Best roll your own 1/4/08 PM Farmers Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. VB - Made in the USA cigarettes 9/20/05 PM ITG Brands, LLC Fortuna cigarettes 12/21/18 PM ITG Brands, LLC Kool cigarettes 6/12/15 PM ITG Brands, LLC Maverick cigarettes 6/12/15 PM ITG Brands, LLC Rave cigarettes 12/12/14 PM ITG Brands, LLC Salem cigarettes 6/12/15 PM ITG Brands, LLC Winston cigarettes 6/12/15 PM Japan Tobacco International Export 'A' cigarettes 5/24/12 PM Japan Tobacco International LD cigarettes 2/22/17 PM Japan Tobacco International Wave cigarettes 7/22/03 PM King Maker Marketing Wildhorse cigarettes 12/13/18 NPM KT&G Corp. -

Tuesday, March 27, 2001

CANADA 1st SESSION · 37th PARLIAMENT · VOLUME 139 · NUMBER 20 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, March 27, 2001 THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 438 THE SENATE Tuesday, March 27, 2001 The Senate met at 2 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. champions. With one more step to climb, albeit a steep one, their dream of a world championship became a reality Saturday night Prayers. in Ogden, Utah. With Islanders in the stands and hundreds of others watching on television at the Silver Fox Curling Club in Summerside, SENATORS’ STATEMENTS these young women put on a show that was at once both inspiring and chilling. It was certainly a nervous time for everyone because those of us who have been watching all week QUESTION OF PRIVILEGE knew that the team Canada was playing in the finals was not only the defending world champion but the same team that had UNEQUAL TREATMENT OF SENATORS—NOTICE defeated Canada earlier in the week during the round robin. With steely determination, the young Canadian team overcame that The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I wish to inform mental obstacle and earned the world championship in the you that, in accordance with rule 43(3) of the Rules of the Senate, process. the Clerk of the Senate received, at 10:52 this morning, written notice of a question of privilege by the Honourable Senator The welcome the Canadian team received last night on their Carney, P.C. -

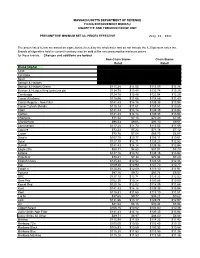

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

The Plot Against Plain Packaging

The Plot Against Plain Packaging How multinational tobacco companies colluded to use trade arguments they knew were phoney to oppose plain packaging. And how health ministers in Canada and Australia fell for their chicanery. Physicians for Smoke-Free Canada 1226A Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario, K1Y 1R1 www.smoke-free.ca April, 2008 (version 2) The government recognizes that lower taxes and therefore lower prices for legally purchased cigarettes may prompt some people, particularly young Canadians, to smoke more. That is why the government will take strong action to discourage smoking, including legislated and regulatory changes to ban the manufacture of kiddie packs targeted at young buyers, raise the legal age for purchasing cigarettes, increase fines for the sale of cigarettes to minors, drastically restrict the locations for vending machines, and make health warnings on tobacco packaging more effective. We will also examine the feasibility of requiring plain packaging of cigarettes and will also ask the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health to make recommendations in this area. We are also launching immediately a comprehensive public education campaign including a national media campaign to make young people aware of the harmful effects of smoking; new efforts to reach families, new parents and others who serve as role models for children; support of school education programs; increased efforts to reach young women who are starting Prime Minister Jean Chrétien House of Commons February 8, 1994. TABLE OF CONTENTS SYNOPSIS .......................................................................................... 2 PROLOGUE: TOBACCO IN THE WINTER OF 1994 ................................. 3 ACT 1: A NEW IDEA FOR HEALTH PROTECTION ................................. 7 Scene 1: The health side sets the stage................................................. -

Ceylon Tobacco Company Plc Annual Report 2020

The Next CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC Step ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents Overview Our ESG Performance Financial Statements 2 CTC at a Glance 54 Environment 100 Finance Director’s Review 3 The Year in Numbers 59 Social 102 Financial Reporting Calendar 4 About the Report 64 Governance 103 Independent Auditor's Report 6 Our New Corporate Logo 105 Statement of Profit or Loss and other Our Leadership 7 Our Response to COVID-19 Comprehensive Income 68 Board of Directors 8 Performance Highlights 106 Statement of Financial Position 72 Executive Committee 107 Statement of Changes in Equity Executive Review and 108 Statement of Cash Flows Strategic Positioning Governance and Risk 109 Notes to the Financial Statements 10 Chairman’s Review 76 Board Governance 143 Statement of Value Added 14 Managing Director & CEO’s Review 77 Driving Strategy and Performance 18 Value Creation Model 80 Compliance Overview Supplementary Information 82 Corporate Governance 20 Value Creation and Trade-offs 144 Share Information 85 Risk Management 22 Strategy for Accelerated Growth 148 Notes 88 Assessment of Going Concern 24 Industry Overview 151 Notice of Meeting 89 Statement of Internal Controls 25 Our Sustainability Agenda 152 AGM 2021 Instructions to Shareholders 90 Report of the Board of Directors 26 Stakeholder Value 153 Form of Proxy 93 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 28 Material Matters 155 Appendices for Financial Statements IBC Corporate Information Performance and Value Creation 94 Report of the Audit Committee 30 Delivering our Strategy 96 Report of the Related Party Transactions 30 Illicit Trade and Beedi Review Committee 32 Product Responsibility 97 Report of the Board Compensation and 34 Optimising the Manufacturing Footprint Remuneration Committee 36 Leveraging Our Brands 98 Report of the Nominations Committee 38 Our Product SKUs 40 Sustainable Supply Chain 43 Strength in Distribution 45 Managing People 50 Ensuring a Safe Working Environment Online references: http://www.ceylontobaccocompany.com Scan the QR Code with your smart device to view this report online. -

Ceylon Tobacco Company Plc Annual Report 2016 an Overview of Our Business

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC ABOUT THIS REPORT Ceylon Tobacco Company PLC (CTC) and material issues that may potentially Sri Lanka and the Securities and Exchange first embraced the principles of Integrated have an impact on our ability to create Commission of Sri Lanka and the GRI Reporting in 2015, and this year we hope value. The material issues included herein G4 Guidelines. The financial information to build on the foundation put in place were selected through a structured and presented herein is in compliance with the last year to clearly and comprehensively comprehensive process as detailed on Sri Lanka Financial Reporting Standards, articulate our commitment to creating value pages 64 and 65 of this Report. For and external assurance on the same for all our stakeholders. As our primary sustainability reporting, we have adopted has been provided by Messers KPMG report to stakeholders, this Integrated the criteria prescribed by the Global (Chartered Accountants). Annual Report demonstrates the Company’s Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 Framework, commitment to developing and directing building on the previous report for the year REPORTING ENHANCEMENTS strategy in a manner that balances the ending 31 December 2015. We understand that Integrated Reporting competing interests of our stakeholders and is a continuously evolving journey, and this provides details on emerging risks and REPORTING PRINCIPLES AND year we have sought to further improve opportunities, successes and challenges ASSURANCE the meaningfulness and readability of our in delivering value and our strategies and This report has been prepared based Report through, targets going forward. on the guidelines of the Integrated Reporting (IR) Framework published by • Enhanced connectivity of information SCOPE AND BOUNDARY the International Integrated Reporting through linking the narrative to our The Company’s Integrated Report is Council. -

PTC Annual Report 2018

Celebrating Diversity And Inclusion Soaring through the decades, Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited has achieved uncountable successes. Throughout this journey, our focus has been to make the organisation more Diverse & Inclusive. By doing this, we have been able to create an environment that includes individuals of different ages, genders, backgrounds, cultures and beliefs making them a part of this big PTC family. 1 Table of Contents 04 12 26 42 68 80 Our Vision Our Partnerships Organisational Committees of the Operational Horizontal & Structure Board Excellence Vertical Analysis 04 16 28 44 70 82 Our Mission Our Guiding Position of Report of Audit Corporate Social Analysis of Principles Reporting Committee Responsibility Statement of Profit Organisation within or Loss & Statement Value Chain of Financial Position 05 18 30 46 72 84 Our Guiding Our Initiatives Strategic Objectives Standards of Calendar of Notable Summary of Principles Business Conduct & Events 2018 Statement of Profit Ethical Principles or Loss, Financial Position & Cash flows 06 20 32 53 73 85 British American Our Achievements Risk & Opportunity Chairman’s Review 2018 Performance Dupont Analysis Tobacco (BAT) Report 2018 07 22 36 55 74 86 BAT’s Geographical Our Exported Talent Illicit trade: Threat MD/CEO’s Message Critical Performance Liquidity, Cash Flows Spread to legitimate Indicators and Capital Structure industry’s sustainability 08 24 37 56 76 88 Pakistan Tobacco Our People Our Corporate Director’s Report Quarterly Analysis Performance Company Limited Pride Information -

Pub 302 WI Alcohol Beverage And

State of Wisconsin Department of Revenue Wisconsin Alcohol Beverage and Tobacco Laws for Retailers Publication 302 (12/16) Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................3 II. DEFINITIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 III. ALCOHOL BEVERAGE LAW ............................................................................................................5 A. Closing Hours ..................................................................................................................................5 B. Daylight Saving Time ......................................................................................................................5 C. Training Requirements For Completion Of The Responsible Beverage Server Training Course (Required As A Condition Of Licensing) ........................................................................................6 IV. LICENSING ..........................................................................................................................................6 V. SALE OF ALCOHOL BEVERAGES ...................................................................................................6 VI. SELLER’S PERMIT..............................................................................................................................6 VII. FEDERAL TAX STAMP .......................................................................................................................7 -

Annual Report 2020

British American Tobacco (2012) Limited Registered Number 08277101 Annual report and financial statements For the year ended 31 December 2020 British American Tobacco (2012) Limited Contents Strategic report .................................................................................................................................... 2 Directors’ report ................................................................................................................................... 4 Independent auditor's report to the members of British American Tobacco (2012) Limited ............... 6 Profit and loss account and statement of changes in equity ............................................................... 9 Balance sheet .................................................................................................................................... 10 Notes to the financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2020 ........................................ 11 British American Tobacco (2012) Limited Strategic report The Directors present their strategic report on British American Tobacco (2012) Limited (the “Company”) for the year ended 31 December 2020. Principal activities The Company’s principal activity is the holding of investments in companies operating in the tobacco and nicotine industry as members of the British American Tobacco p.l.c. group of companies (the “Group”). Review of the year ended 31 December 2020 The profit for the financial year attributable to British American Tobacco (2012) Limited shareholders -

Wednesday, June 1, 1994

VOLUME 133 NUMBER 076 1st SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, June 1, 1994 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, June 1, 1994 The House met at 2 p.m. and not merely wishful thinking, and urge the CBC to provide adequate television coverage of our disabled athletes at the next _______________ Summer Games. Prayers In doing so, we will express the admiration and respect which their exceptional achievements deserve. _______________ * * * STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS [English] [English] BILLS C–33 AND C–34 LAW OF THE SEA Mr. John Duncan (North Island—Powell River): Mr. Speaker, yesterday we had the introduction of Bills C–33 and Hon. Charles Caccia (Davenport): Mr. Speaker, straddling C–34 which would ratify land claims and self–government the 200 nautical mile limit there is a fish stock which is of great agreements in Yukon. Last week we were told the government importance to the existence and well–being of many coastal wished to have these bills introduced later in June with the communities in Atlantic Canada. understanding that MPs would have time to prepare properly. Designed to avoid crisis in the fisheries, the law of the sea These bills represent the culmination of 21 years of mostly affirms the responsibility of all nations to co–operate in con- behind closed doors work without the involvement of federal serving and managing fish in the high seas. It is in the interests parliamentarians. Today, 24 hours after tabling, Parliament is of Canadians that the Government of Canada ratify the law of being asked to debate these bills at second reading.