Monograph 13: Marketing Cigarettes with Low Machine-Measured Yields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menthol Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation Behaviour: a Review of Tobacco Industry Documents Stacey J Anderson1,2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Research paper Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behaviour: a review of tobacco industry documents Stacey J Anderson1,2 1Department of Social and ABSTRACT The concentration of menthol in tobacco prod- Behavioral Sciences, University Objective To determine what the tobacco industry knew ucts varies according to the product and the flavour of California, San Francisco about menthol’s relation to smoking cessation behaviour. desired, but is present in 90% of all tobacco prod- (UCSF), San Francisco, ‘ ’ ‘ ’ 2 3 California, USA Methods A snowball sampling design was used to ucts, mentholated and non-mentholated . 2Center for Tobacco Control systematically search the Legacy Tobacco Documents Studies in the peer-reviewed academic literature of Research and Education, Library (LTDL) (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) between 15 the association of menthol smoking and cessation University of California, San May to 1 August 2010. Of the approximately 11 million have yielded conflicting findings. One reason for Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco, California, USA documents available in the LTDL, the iterative searches inconsistencies is differences in study design (eg, returned tens of thousands of results. A final collection of clinical treatment studies, population-based Correspondence to 509 documents relevant to 1 or more of the research studies), and another is differences in cessation Stacey J Anderson, Department questions were qualitatively analysed, as follows: (1) outcomes (eg, length of time abstinent, length of of Social and Behavioral perceived sensory and taste rewards of menthol and time to relapse, number of quit attempts) across Sciences, Box 0612, University fi of California, San Francisco potential relation to quitting; and (2) motivation to quit studies. -

Tobacco Deal Sealed Prior to Global Finance Market Going up in Smoke

marketwatch KEY DEALS Tobacco deal sealed prior to global finance market going up in smoke The global credit crunch which so rocked £5.4bn bridging loan with ABN Amro, Morgan deal. “It had become an auction involving one or Iinternational capital markets this summer Stanley, Citigroup and Lehman Brothers. more possible white knights,” he said. is likely to lead to a long tail of negotiated and In addition it is rescheduling £9.2bn of debt – Elliott said the deal would be part-funded by renegotiated deals and debt issues long into both its existing commitments and that sitting on a large-scale disposal of Rio Tinto assets worth the autumn. the balance sheet of Altadis – through a new as much as $10bn. Rio’s diamonds, gold and But the manifestation of a bad bout of the facility to be arranged by Citigroup, Royal Bank of industrial minerals businesses are now wobbles was preceded by some of the Scotland, Lehmans, Barclays and Banco Santander. reckoned to be favourites to be sold. megadeals that the equity market had been Finance Director Bob Dyrbus said: Financing the deal will be new underwritten expecting for much of the last two years. “Refinancing of the facilities is the start of a facilities provided by Royal Bank of Scotland, One such long awaited deal was the e16.2bn process that is not expected to complete until the Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Société takeover of Altadis by Imperial Tobacco. first quarter of the next financial year. Générale, while Deutsche and CIBC are acting as Strategically the Imps acquisition of Altadis “Imperial Tobacco only does deals that can principal advisors on the deal with the help of has been seen as the must-do in a global generate great returns for our shareholders and Credit Suisse and Rothschild. -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

"I Always Thought They Were All Pure Tobacco'': American

“I always thought they were all pure tobacco”: American smokers’ perceptions of “natural” cigarettes and tobacco industry advertising strategies Patricia A. McDaniel* Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, School of Nursing University of California, San Francisco 3333 California Street, Suite 455 San Francisco, CA 94118 USA work: (415) 514-9342 fax: (415) 476-6552 [email protected] Ruth E. Malone Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, School of Nursing University of California, San Francisco, USA *Corresponding author The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Tobacco Control editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://tc.bmj.com/misc/ifora/licence.pdf). keywords: natural cigarettes, additive-free cigarettes, tobacco industry market research, cigarette descriptors Word count: 223 abstract; 6009 text 1 table, 3 figures 1 ABSTRACT Objective: To examine how the U.S. tobacco industry markets cigarettes as “natural” and American smokers’ views of the “naturalness” (or unnaturalness) of cigarettes. Methods: We reviewed internal tobacco industry documents, the Pollay 20th Century Tobacco Ad Collection, and newspaper sources, categorized themes and strategies, and summarized findings. Results: Cigarette advertisements have used the term “natural” since at least 1910, but it was not until the 1950s that “natural” referred to a core element of brand identity, used to describe specific product attributes (filter, menthol, tobacco leaf). -

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

Tobacco Directory Deletions by Manufacturer

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Manufacturer Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed Catmandu Alternative Brands, Inc. 2/3/2006 Savannah Anderson Tobacco Company, LLC 11/18/2005 Desperado - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Peace - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Revenge - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 The Brave Bekenton, S.A. 6/2/2006 Barclay Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Belair Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Private Stock Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Raleigh Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/6/2005 2004 Viceroy Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/3/2010 2004 Coronas Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Palace Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Record Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 VL Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Freemont Caribbean-American Tobacco Corp. 5/2/2008 Kingsboro Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Roger Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Aura Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne - RYO Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Decade Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Bridgeton CLP, Inc. 5/4/2007 DT Tobacco - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Railroad - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Smokers Palace - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Smokers Select - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Southern Harvest - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 7/19/2016 Malibu Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 5/31/2017 McClintock - RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. -

OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021

OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021 Owner Information Business Information Permit Number 4700114 A & E WHOLESALE OF NORTH FLORIDA, LLC A & E WHOLESALE OF NORTH FLORIDA, LLC POST OFFICE BOX 21 1023 CAPITAL CIRCLE NW TALLAHASSEE, FL 32302 TALLAHASSEE, FL 32304 Permit Number 6200236 A & J DISTRIBUTING CORP A & J DISTRIBUTING CORP 3880 69TH AVE 3880 69TH AVE PINELLAS PARK, FL 33781 PINELLAS PARK, FL 33781 Permit Number 5800250 ABC LIQUORS INC ABC LIQUORS INC PO BOX 593688 8989 SOUTH ORANGE AVENUE ORLANDO, FL 32859-3688 ORLANDO, FL 32824 Permit Number 2600353 ADEL WHOLESALE ADEL WHOLESALE 2500 CHARLEVOIX ST 2500 CHARLEVOIX ST JACKSONVILLE, FL 32206 JACKSONVILLE, FL 32206 Permit Number 3900610 ALFA DISTRIBUTING INC ALFA DISTRIBUTING INC 18103 REGENTS SQ DRIVE 18103 REGENTS SQ DRIVE TAMPA, FL 33647 TAMPA, FL 33647 Permit Number 3900605 ALKEIF COFFEE & SMOKE SHOP ALKEIF COFFEE & SMOKE SHOP 4815 E. BUSCH BLVD. 110 BUTLER RD SUITE 103 BRANDON, FL 33511 TAMPA, FL 33617 Permit Number 7900040 ALTADIS U.S.A., INC. ALTADIS U.S.A., INC. 5900 N ANDREWS AVE 600 PERDUE AVENUE FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33309 RICHMOND, VA 23224 Permit Number 3900405 ALTADIS USA INC ALTADIS USA INC 5900 N ANDREWS AVE 2601 H. TAMPA EAST BLVD FORT LAUDERDALE, FL 33309 TAMPA, FL 33619 Page 1 of 27 OTP Wholesalers September 28, 2021 Owner Information Business Information Permit Number 3900598 AMERICAN COMMERCIAL GROUP LLC AMERICAN COMMERCIAL GROUP LLC 12634 NICOLE LN 5705 HANNA AVE TAMPA, FL 33625 TAMPA, FL 33610 Permit Number 7900073 ANDALUSIA DISTRIBUTING CO INC ANDALUSIA DISTRIBUTING CO INC P O BOX 51 115 ALLEN AVE ANDALUSIA, AL 36420 ANDALUSIA, AL 36420 Permit Number 1614252 ASSOCIATED GROCERS OF FLORIDA INC ASSOCIATED GROCERS OF FLORIDA INC 1141 SW 12TH AVE 1141 SW 12TH AVE POMPANO BEACH, FL 33069 POMPANO BEACH, FL 33069 Permit Number 7900030 ATLANTIC DOMINION DISTRIBUTORS ATLANTIC DOMINION DISTRIBUTORS P.O. -

EEMEA Regional Overview

"The material in this presentation is provided for the purpose of giving information about us to investors and is not provided for tobacco product advertising, promotional or marketing purposes. This material does not constitute and should not be construed as constituting an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any of our tobacco products. Our products are sold only in compliance with the laws of the particular jurisdictions in which they are sold". EEMEA Region Andrew Gray EEMEA A diverse region with a large consumption base and growing industry value • EEMEA: 80+ markets with 2 of the biggest markets in the world • T40 average disposable income +10% CAGR 2012‐2020 (Inflation +7%) • Premium Segment up by 1.7pp to 143bn in 2012 • ASU30 Smokers at 32% • Instability in the Middle East and North Africa • Excise‐driven price increases Source: BAT estimates (T40 Markets Only), Euromonitor The tobacco industry in EEMEA A diverse region with a large consumption base and growing industry value CAGR 2010- DIMENSION 2010 2012 2012 Consumption volume (bn) 1,089 1,136 +2.1% Duty Paid (bn) 1,000 1,014 +0.7% Illicit trade (bn) 89 122 +17.1% BAT volume (bn) 232 233 +0.4% Industry Value (£bn) 13.6 16.2 +9.0% H1 2013 consumption in T40 ‐3.7% vs 2012 Source: Volumes – internal latest estimates Industry Value - KCM BAT EEMEA is performing well • Growing share in Russia, GCC and Ukraine • Growth of innovation and launch of Rothmans • Investing in RTM • Entry in Morocco • Solid financial performance • Growing talent and diversity Focused investments are translating into positive results Share H1 2013 vs FY 2012 Cigarettes +0.3ppt GDB stable Premium +0.1ppt Sources – Nielsen and BAT internal data, T40 Focused investments are translating into positive results FY2010 ‐ FY2012 Financials H12012 – H12013 Average growth p.a. -

Las Vegas Daily Gazette, 07-30-1881 J

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Las Vegas Gazette, 1880-1886 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 7-30-1881 Las Vegas Daily Gazette, 07-30-1881 J. H. Koogler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lv_gazette_news Recommended Citation Koogler, J. H.. "Las Vegas Daily Gazette, 07-30-1881." (1881). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lv_gazette_news/21 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Las Vegas Gazette, 1880-1886 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' á I LAS VEGAS DAILY GAZETTE O fc . , . VOL. 3. SATURDAY MORNING-;- ' JULY 30, 1881. NO. 21. ' SIMON A CLEMENTS. FELIX MARTINEZ. Keene's Jfw Company. The Oallawa In Leadville. Expert and Imperta. Chicago. July 29. A special from Lead ville. July 29. --Gilbert and Rosen- - Washington, 0 'uy 29. The excess of HEWS BV TELEGRAPH New York says Keene's new telegraph crants paid the penalty of their crimes exports of merck Li ndise over imports CLEMENTS MARTINEZ company was formally organized to- upon the scanold this morning. J. he during the year ciic'ing Juue 30, i x.vt I day. It is becoming quite fashionable streets were thronged with people from was 1259,720,25-i- , t igainst 1C7.083.912 DEALERS IN nowadays for millionaires and promi- daylight, and long before seven o'clock during the previ- - ous fiscal year. Excess nent Wall Street operators to control the gallows was surrounded by thou- of imports of gol d f or the past fiscal The Sews Front the White House Con- organizations of this character and fol-- sands of people. -

Directory for Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL STATE OF HAWAI‘I DIRECTORY FOR CIGARETTES AND ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers Their Brands and Brand Families (Available at: http://ag.hawaii.gov/cjd/tobacco-enforcement-unit/) DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 425 QUEEN STREET HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I 96813 (808) 586-1203 INDEX I. Directory: Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco Page 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. DEFINITIONS 3 3. NOTICES 6 II. Update Summary For January 2, 2019 Posting * III. Alphabetical Brand List IV. Compliant Participating Manufacturers List V. Compliant Non-Participating Manufacturers List Posted: Jan. 2, 2019 (last update 9/5/2018) 2 1. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5(a), beginning December 1, 2003, it shall be unlawful for an entity to (1) affix a stamp to a package or other container of cigarettes belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory, or (2) import, sell, offer, keep, store, acquire, transport, distribute, receive, or possess for sale or distribution cigarettes1 belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory. Pursuant to §245-22.5(b), any entity that knowingly violates subsection (a) shall be guilty of a class C felony. Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §§245-40 and 245-41, any cigarettes unlawfully possessed, kept, stored, acquired, transported, sold, imported, offered, received, or distributed in violation of Haw. Rev. Stat. Chapter 245 may be seized, confiscated, and ordered forfeited pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat., Chapter 712A. In addition, the attorney general may apply for a temporary or permanent injunction restraining any person from violating or continuing to violate Haw. -

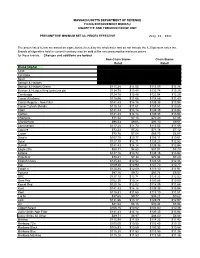

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

The London Cigarette Card Company Limited

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] POSTAL AUCTION ENDING SATURDAY 25TH JULY 2020 CATALOGUE OF CIGARETTE & TRADE CARDS & OTHER CARTOPHILIC ITEMS TO BE SOLD BY POSTAL AUCTION Bids can be submitted by post, phone, fax, e-mail or through our website. Estimates include VAT. Successful bidders outside the European Community will have 15% (UK tax) deducted from prices realized. Abbreviations used: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (89 x 64mm) L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature; Type Card = one card from a set; 27/50 = 27 cards out of a set of 50 etc; Under Condition column FCC = Finest Collectable Condition; VG = Very Good; G = Good; F = Fair; P = Poor; VP = Very Poor; O/W = Otherwise; CAT = 2020 Catalogue Value in Very Good Condition. EST in end column = Estimated Value due to condition. TOB in issuer column = Tobacco. See biding sheet for conditions of sale. Last date for receipt of bids Saturday 25th July 2020. There are no additional charges to bidders for buyers premium etc. LOT ISSUER DESCRIPTION CONDITION CAT EST 1 PLAYERS 4 Sets of 50 Association Cup Winners 1930, Cricketers 1930, 1934 and 1938………………….. VP-P £275 £30 2 G PHILLIPS Set 25 Old Favourites (Flowers) 1924……………………………………………………………………… VG £50 £50 3 NATIONAL SPASTICS SOCIETY Set 24 Famous Footballers 1958………………………………………………………….. Mint £20 £20 4 BATTEN (Jibco Tea) Set K25 Screen Stars 2nd Series 1956…………………………………………………………………… Mint £23 £23 5 OGDENS Guinea Gold 56/59 Boer War etc.