MAKING BETTER CONNECTIONS Shoreline Shared-Use Mobility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Annual Report Document De Référence

Vienna 2009 Annual Report Document de Référence TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPANY OVERVIEW 3 Financial highlights 4 The year 2009 6 The outdoor advertising industry 8 One business, three segments 16 Our advertisers 33 Sustainable development 38 Research and development 54 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 58 Management discussion and analysis of group consolidated financial statements 59 Consolidated financial statements and notes 69 Management discussion and analysis of corporate financial statements 128 Corporate financial statements and notes 130 LEGAL INFORMATION 152 Corporate governance, internal control and risk management 153 Shareholders and trading information 179 Share capital 186 Other legal information 189 COMBINED ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS, 19 MAY 2010 205 Agenda 206 Summary of proposed resolutions 207 Proposed resolutions 208 OTHER INFORMATION 211 Statutory auditors’ reports 212 Person responsible for the Annual Report and Persons responsible for the audit of the financial statements 217 Incorporation by reference In accordance with Article 28 of EU Regulation n°809/2004 dated 29 April 2004, the reader is referred to previous “Documents de référence” containing certain information: 1. Relating to fiscal year 2008: - The Management Discussion and Analysis and consolidated financial statements, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 10 April 2009 under number D.09-0229 (pages 51 to 117and 213, respectively). - The corporate financial statements of JCDecaux SA, their analysis, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 10 April 2009 under number D.09-0229 (pages 118 to 141 and 214, respectively). - The statutory auditors’ special report on regulated agreements with certain related parties, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 10 April 2009 under number D.09-0229 (page 216). -

City of Wilsonville Transit Master Plan

City of Wilsonville Transit Master Plan CONVENIENCE SAFETY RELIABILITY EFFICIENCY FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY FRIENDLY SERVICE EQUITY & ACCESS ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY JUNE 2017 Acknowledgements The City of Wilsonville would like to acknowledge the following for their dedication to the development of this Transit Master Plan. Their insight and outlook toward the future of this City helped create a comprehensive plan that represents the needs of employers, residents and visitors of Wilsonville. Transit Master Plan Task Force Planning Commission Julie Fitzgerald, Chair* Jerry Greenfield, Chair Kristin Akervall Eric Postma, Vice Chair Caroline Berry Al Levit Paul Diller Phyllis Millan Lynnda Hale Peter Hurley Barb Leisy Simon Springall Peter Rapley Kamran Mesbah Pat Rehberg Jean Tsokos City Staff Stephanie Yager Dwight Brashear, Transit Director Eric Loomis, Operations Manager City Council Scott Simonton, Fleet Manager Tim Knapp, Mayor Gregg Johansen, Transit Field Supervisor Scott Star, President Patrick Edwards, Transit Field Supervisor Kristin Akervall Nicole Hendrix, Transit Management Analyst Charlotte Lehan Michelle Marston, Transit Program Coordinator Susie Stevens Brad Dillingham, Transit Planning Intern Julie Fitzgerald* Chris Neamtzu, Planning Director Charlie Tso, Assistant Planner Consultants Susan Cole, Finance Director Jarrett Walker Keith Katko, Finance Operations Manager Michelle Poyourow Tami Bergeron, Planning Administration Assistant Christian L Watchie Amanda Guile-Hinman, Assistant City Attorney Ellen Teninty Stephan Lashbrook, -

City of Del Mar Staff Report

City of Del Mar Staff Report TO: Honorable Mayor and City Council Members FROM: Clem Brown, Environmental Sustainability/Special Projects Manager Via Scott Huth, City Manager DATE: May 6, 2019 SUBJECT: License Agreement with Gotcha Ride LLC to Operate the North County Bike Share Pilot Program in the City of Del Mar REQUESTED ACTION/RECOMMENDATION: Staff requests that the City Council approve a license agreement with Gotcha Ride LLC (Attachment A) to operate the North County Coastal Bike Share Pilot Program in the City of Del Mar and authorize the City Manager to execute the agreement. BACKGROUND: The City of Del Mar is committed to reducing local greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to limit the effects of climate change, while also offering viable transportation alternatives to driving. Del Mar has adopted a Climate Action Plan (CAP) that establishes a number of strategies to meet GHG emissions reduction targets, including facilitating safe, convenient, and affordable alternative transportation options. Specifically, Goal 14 in the CAP includes a strategy to “explore implementation of a bike share program…to provide another transportation alternative for traveling in town.” Transportation, especially travel via single occupancy vehicles, is a major source of GHG emissions in Del Mar and the other north San Diego County (North County) coastal cities. Offering and promoting programs like bike share, that replace vehicle trips with bike trips, is one way Del Mar can help to reduce emissions while offering more efficient and more affordable transportation modes for residents, employees, and visitors. Bike share is a service by which bicycles are made available for shared use to individuals on a very short-term basis, allowing them to borrow a bicycle at one location and return it either to the same or an alternate location within a defined geographic boundary. -

Transit Facility Parking Management

2024 Our history is not our future… ST2 & ST3 Sound Transit System Plan Lynnwood Link Daily boardings by station: Today: LTC+MLT = 6,200/day 2024-2035: LTC+MLT = 23,000/day Lynnwood Link Transit Experience on I-5 Today: • Lynnwood to Downtown Seattle • Scheduled at 29 min to 52 min, depending on time of day • Actual travel time is 24 min to 73 min • Downtown Seattle to Lynnwood • Scheduled at 30 min to 45 min, depending on time of day • Actual travel time is 22 min to 86 min • Link will be 28 min, every day, every time Lynnwood Transit Center Bus arrival/departure every 35 seconds Mountlake Terrace Transit Center Shoreline North 185th Station I-405 BRT I-405 BRT SR 522 BRT Bus Service Levels: Annual Bus Service Hours 700 • Re-Investment of Inter-County/I-5 600 500 400 300 200 Thousands of Hours 100 0 2018 2019 2024 Redesigned Commuter Routes Service Concepts • Access to Link • Connect activity centers • North-South • More frequency • More span • New routes Ash Transit Today Way Alderwood Mall City Hall EdCC Lynnwood City Center Station 10-15 min. 30 min. Commuter Ash Transit 2024 Way (concept) More access to Alderwood Frequent buses Mall City Hall EdCC Lynnwood City Center Station Buses at LCC every Commuter Bus Routes 35 seconds at peak Connect to Link at LCC (90 seconds today) 10-15 min. 30 min. Commuter Alternative Services Ridesharing Services Carshare & Bikeshare Micro Transit Van Programs & On-Demand Connections Business/Community Shuttles Transit Facility Parking Management On-Demand Bicycle Parking HOV Parking Permit Programs Private -

City Partnerships Helped Make E Line Service Better

February 2014 Line Starting February 15, riders traveling along Aurora Avenue N between Shoreline, north Seattle and downtown Seattle will experience the benefits of RapidRide. Improving speed and reliability RapidRide includes many features that will make travel on this heavily used corridor more reliable and quick. These include roadway improvements such as transit signal priority through busy intersections and the spacing of bus stops about every half-mile. In partnership with the cities of Shoreline and Seattle, BAT (business access and transit) lanes are provided along nearly the full length of the corridor to help buses get through congestion. Funded by the 2006 Transit Now initiative that started Metro’s RapidRide also uses a fare RapidRide program, the E Line—the fifth of six RapidRide payment system that speeds lines—is ready to launch. Ridership has grown quickly on the up boarding. At stations with first four RapidRide lines, which serve busy corridors around off-board ORCA card readers, King County. The A and C lines reached their five-year rider- customers who have ORCA ship goals in only two years. Rider satisfaction is high on all cards can pay their fares before RapidRide lines. getting on the bus and may board at the back doors. Riders Frequent service makes bus riding convenient using paper bus transfers may The hallmark of RapidRide is frequent service. The E Line will also board at the back doors at operate: any RapidRide stop, while riders paying with cash or tickets will board at the front door. Fare enforcement officers will • Weekdays—every 5-12 minutes during peak hours and make sure passengers have paid fares correctly. -

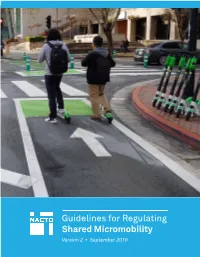

Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility Section 1

Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility Section 1 Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility Version 2 September 2019 1 Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility 1. Regulating Shared Micromobility 5 a. What is Shared Micromobility? 5 b. City Authority for Regulation 6 c. Options for Regulation 7 2. General Terms and Conditions 9 a. General Provisions 10 b. Insurance, Bonds, and Fees 11 c. Enforcing Permit Terms 12 3. Scope & Operations Insight 15 a. Fleet Size 16 b. Fleet Removal/Relocation 18 c. Rebalancing & Fleet Distribution 19 d. Equipment and Vehicle Maintenance 20 e. Customer Service 23 f. Staffing and Workforce Development 24 g. Pricing 25 4. Public Engagement 27 a. Staffing & Events 28 b. Outreach Materials & Campaigns 28 c. Pricing & Discount Programs 29 5. Mobility Data & User Privacy 31 6. Infrastructure 35 a. Shared Micromobility Parking 36 b. Providing Safe Place to Ride 40 c. Restricted/Limited Access Areas 41 7. Current State of Practice 43 a. Vehicle Requirements 44 b. Fleet Requirements 45 c. Data Requirements 48 d. Fees 49 e. Employment Requirements 51 f. Adaptive Device Requirements 52 g. Discounted Pricing Programs 53 h. Multi-Language Requirements 54 i. Parking Requirements 55 2 Cover credit: San Jose Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility About Developed for cities, by cities, this guidance outlines best practices for cities and public entities regulating and managing shared micromobility services on their streets. While many of the issues covered are applicable to all forms of shared micromobility, this document is explicitly meant to help cities establish guidelines for formal management of public-use mobility options that are not managed through traditional procurement processes (the management mechanism for most docked bike share programs in North America). -

Recap: Pwx 2019 in Seattle

FALL 2019 RECAP: PWX 2019 IN SEATTLE Inside: Looking at Transportation | Crossing the Cascades – Part Two The organization of choice in providing public works education, advocacy, expertise, and public awareness for its diverse community of members. 2601 Fourth Avenue, Suite 800, Seattle, WA 98121-1280 GUARANTEED PERMANENT • WORKS IN WATER & ALL WEATHER Available in bulk, 50 lb bags & bulk sacks For more information contact: Rob Rosson, Sales Director 425-313-2681 www.lakesideindustries.com [email protected] EZ Street® and the EZ Street Logo are registered trademarks of Asphalt Research Technology, Inc. © Copyright 2017 Covering Washington Bellevue / Everett / Seattle / Spokane / Tacoma / Vancouver FALL 2019 WASHINGTON STATE PublicWorks 3 Issaquah’s Rainier Boulevard LID Transportation Architecture Aviation Landscape Architecture Urban Design Land Surveying Construction Management Traffic Engineering Transportation Planning Public Involvement Town Visioning Stormwater Utilities Interdisciplinary Design www.kpg.com The Quality Stormwater Management System. With BMP’s advanced products—like the SNOUT®, Bio-Skirt® and our new Turbo Plate®, reducing pollutants in stormwater runoff has never been easier. Made in the USA with over 80,000 SNOUTs installed since 1999. The Stormwater Quality Experts For more information on how our system can solve your stormwater quality 20TH ANNIVERSARY issues, contact us at 800.504.8008 or visit us at bmpinc.com. 4 WASHINGTON STATE PublicWorks FALL 2019 15 2601 Fourth Avenue, Suite 800 Seattle, WA 98121-1280 washington.apwa.net Federal tax #36-2202880 2019 OFFICERS President Lorelei Williams, PE Vice President Donald J. Huling, PE Secretary Scott Sawyer, PE Treasurer Lauren Behm Past President Scott Egger, PE Features: 2019–2020 Directors Bob Desgrosellier Thanh Jeffers PWX 2019 Conference Recap ............................................11 Scott Rood A look at some of the highlights from PWX 2019 held in Seattle in September at the Molly Toy Washington State Convention Center. -

Full Draft Long Range Plan February 2018

CONNECTING YOUR FUTURE Everett Transit DRAFT LONG RANGE PLAN Everett Transit Long Range Plan 1 Connecting Your Future 2 Connecting Your Future Table of CONTENTS i Executive Summary i 1 Why a Long Range Plan? 1 2 Transit Today and in the Future 4 3 Everett Transit’s Role 10 4 Our Plan to Move Forward 13 5 Our Financial Future 16 6 Strategy for Implementation 19 Everett Transit Draft Long Range Plan Everett Transit Long Range Plan 3 Connecting Your Future The Goals of the Plan Everett Transit provides safe, customer-focused, cost-efficient, and effective public transit and transportation management services in support of sustainable growth and a livable community. This Long Range Plan services three main goals: 1 Identify future transit service 2 Determine options for implementation 3 Establish service standards Everett Transit Draft Long Range Plan i Everett Transit Long Range Plan i How the Community Helped Develop a Growth Network Plan Everett Transit went out to the community throughout 2017 to help define the vision for transit in the future and to gather feedback on how service should be provided to support continued growth in the region. Respondents described the role they see for Everett Transit in the region and they highlighted their priorities for transit. What We Heard Provide a locally-focused transit network with high frequency and expanded service hours that connects to key destinations and regional transit services. Everett Transit Growth Network Route Frequency (Peak) !#"5 Marysville 15-20 MInutes 30 Minutes E M r a D ri -

APPENDIX B. FLM STRATEGIES TOOLKIT Introduction to the FLM Strategies Toolkit

APPENDIX B. FLM STRATEGIES TOOLKIT Introduction to the FLM Strategies Toolkit This toolkit provides detailed information on 37 REUSE OF EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE TRANSPORTATION SERVICE discrete FLM strategies. The toolkit is organized by FLM strategy theme. • Curbside Management • On-Demand Microtransit Each toolkit sheet includes: • Innovative Park-n-Ride Management • Shuttle Service • Support Implementation of Micromobility Service • Description of the strategy • Car Share Parking • Applicability of the strategy to each FLM • Preferential Parking for Car or Vanpool Vehicles • Special Event Transit Service typology • Prioritization of RTD Owned Land and Parking • Autonomous Transit • Applicability of the strategy to any of the six • Point-to-point Car Share FLM overlays • Provide Power • Key implementing agencies • Round-trip Car Share • Potential funding sources • A case study or resource pertaining to the strategy, including a link for more information NEW INFRASTRUCTURE TRANSPORTATION DEMAND MANAGEMENT • Bicycle and Micromobility Parking and Storage • Creation of EcoPass District • Multimodal Maps and Wayfinding • Bicycle Education and Encouragement Programs • Bike End-of-Trip Facilities and Amenities • Promotion of RTD Discount Passes • Website or App • Guaranteed Ride Home (GRH) • Variable Message Signs FIRST AND LAST MILE GENERAL GUIDANCE • Dynamic Carpooling to Transit • Transit Access Marketing Plan • Pedestrian-Scale Lighting • Commuter Expert or Commuter Buddy • Improve Bicycle and Micromobility Infrastructure • Parking Cash-Out -

The Growing Transit Communities Strategy

The Growing Transit Communities Strategy October 2013 Puget Sound Regional Council PSRC The Growing Transit Communities Partnership is funded by the Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grant Program of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Additional funding for this document provided in part by member jurisdictions, grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration and Washington State Department of Transportation. The work that provided the basis for this publication was supported by funding under an award with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The author and publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government. PSRC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. For more information, or to obtain a Title VI Complaint Form, see http://www.psrc.org/about/public/titlevi or call 206-464-4819. American with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information: Individuals requiring reasonable accommodations may request written materials in alternate formats, sign language interpreters, physical accessibility accommodations, or other reasonable accommodations by contacting the ADA Coordinator, Thu Le, at 206.464.6175, with two weeks’ advance notice. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may contact the ADA Coordinator, Thu Le, through TTY relay 711. Servicios de Traducción Disponible 206-971-3052, Diana Martinez. Có dịch vụ thông dịch sang tiếng Việt. -

Draft City of Shoreline

November 26, 2012 Workshop Dinner Meeting DRAFT CITY OF SHORELINE SHORELINE CITY COUNCIL SUMMARY MINUTES OF WORKSHOP DINNER MEETING Monday, November 13, 2012 Conference Room 104 - Shoreline City Hall 5:45 p.m. 17500 Midvale Avenue N. PRESENT: Mayor McGlashan, Deputy Mayor Eggen, and Councilmembers Hall, McConnell, Roberts, Salomon, and Winstead ABSENT: none STAFF: Julie Underwood, City Manager; Debbie Tarry, Assistant City Manager; Ian Sievers, City Attorney; Kirk McKinley, Transportation Manager; Alicia McIntire, Senior Transportation Planner; Scott Passey, City Clerk GUESTS: David Hull, Supervisor of Service Planning, King County Metro; Chris O’Claire, Supervisor of Strategic Planning and Analysis, King County Metro At 5:54 p.m., the meeting was called to order by Mayor McGlashan, who presided. There were introductions around the table. David Hull, Supervisor of Service Planning, and Chris O’Claire, Supervisor of Strategic Planning and Analysis, provided a presentation on several items, including: 1. Status of RapidRide E Line implementation 2. Funding outlook 3. September service changes 4. Light rail service integration During the presentation and ensuing discussion, the following points were addressed: RapidRide as a premium Metro service, composed of A, B, and E lines RapidRide E-line implementation schedule Traffic signalization and timing questions, expectation of growth in ridership King County actions to preserve bus service, including repurposing of hours, a cut in 75,000 bus hours, union negotiations, and efficiencies 25% fare -

Appendix F-1: Westside Service Enhancement Plan

Appendix F-1: Westside Service Enhancement Plan The following pages are an excerpt from the Westside Service Enhancement Plan showing the direct reference to the Red Line Extension. The full plan is available at https://trimet.org/future/pdf/westside-report.pdf. • Merlo to Progress Ridge/Tigard Extension of service south of the Merlo Rd/158th Ave MAX station connecting with South Beaverton, the Progress Ridge Townsquare, and the Tigard Transit Center. • Willow Creek to the North Hillsboro Industrial Area Extension of service to Cornell Rd., Orenco, Intel Ronler Acres, and the North Hillsboro Industrial Area via Shute Rd. and Brookwood Parkway. Downtown Portland to Progress Ridge Opportunities for action • Extension of peak period express service from Realign bus routes to strengthen a more complete downtown Portland to Progress Ridge north-south and east-west grid, extend MAX Red Townsquare. Line service to Hillsboro and provide frequent or • Downtown Hillsboro to Downtown Beaverton express services on key north- south corridors. New bus line running between Hatfield Complete the grid of bus lines Government Center and Beaverton Transit Extend or change eight bus routes so they better Center via Baseline Rd. and Jenkins Rd. connect with areas of current development and connecting downtown Hillsboro, Willow Creek future growth–residential and employment—and Transit Center, Nike, Cedar Hills Crossing and with MAX and Frequent Service Lines, especially Beaverton Transit Center. going north-south. Improvements include: • North Hillsboro to South Hillsboro Realigned bus service running from Intel Jones Farm to the future South Hillsboro via Brookwood Ave. and TV Highway and connect- ing with MAX at the Fair Complex/Hillsboro Airport Station.