Scottish Birds 38:3 (2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

HIGHLAND – July 2021 See North East Scotland & Scottish Islands

HIGHLAND – July 2021 see North East Scotland & Scottish Islands NCN Cycle Route Map: £8.99 78A: The Caledonia Way North, Oban to Inverness (2016) Pocket sized guides to the NCN: £2.99 42: Oban, Kintyre & The Trossacks Cycle Map (2016) 46: Cairngorms & The Moray Coast Cycle Map (2016) 47: Great Glen & Loch Ness Cycle Map (2016) 48: John o'Groats & North Scottish Coast Cycle Map (2016) http://shop.sustrans.org.uk/ to order on-line (7/21) The North Coast 500 Cyclists Route, to and from Inverness, venturing round the capital of the Highlands, up the West Coast and back via the rugged north coast. www.northcoast500.com/itinerary/cycling.aspx for details (7/21) Cycling Scotland's North Coast (The North Coast 500), Nicholas Mitchell £9.99 or Ebook £7.99 (2018) www.crowood.com/details.asp?isbn=9781785004711&t=Cycling-Scotland to order on-line (7/21) Discover the Caledonian Canal by Bike, the following sections are available to cyclists: Corpach/Gairlochy Rd (OS 41, GR 09 76/17 84) 7 mls Aberchalder Bridge/Fort Augustus Basin (OS 34, GR 33 03/37 09) 4 mls Dochgarroch Locks/Muirtown Basin (OS 26, GR 61 40/65 46) 6 mls www.scottishcanals.co.uk/activities/cycling/caledonian-canal/ for details (6/21) Great Glen Way Map £14.50 (XT40 Edition) www.harveymaps.co.uk to order on-line The Great Glen Way Map £9.95 (2017) www.stirlingsurveys.co.uk/paths.php to order on-line Great Glen Way, Jacquetta Megarry & Sandra Bardwell £13.99 (6th Edition 2020) www.rucsacs.com/books to order on-line Great Glen Way, Fort William to Inverness, Jim Manthorpe £12.99 (2nd -

Salt Exploitation and Landscape Structure in a Breeding Population of the Threatened Bluethroat (Luscinia Svecica) in Salt-Pans in Western France

Biological Conservation 107 (2002) 283–289 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Salt exploitation and landscape structure in a breeding population of the threatened bluethroat (Luscinia svecica) in salt-pans in western France T. Geslina,*, J.-C. Lefeuvrea, Y. Le Pajoleca, S. Questiaub, M.C. Eyberta aUMR 6553 ECOBIO, Universite´ de Rennes I, Avenue du Ge´ne´ral Leclerc, 35042 Rennes cedex, France bLaboratoire d’Ecologie animale, Universite´ d’Angers, 2 Boulevard Lavoisier, Campus Belle-Beille, 49045 Angers cedex, France Received 12 June 2001; received in revised form 10 January 2002; accepted 10 January 2002 Abstract The Gue´ rande salt-pans represent the main French breeding area of bluethroat, a migrating passerine. Salt exploitation has cre- ated a geometrical artificial landscape in which we investigated factors influencing spatial distribution and breeding success of this species using a Geographical Information System. We compared data for four sites in these salt-pans, for three zones in the most densely populated site, and for 2500 m2 grid cells defined for this same site. This study showed the influence of (1) the level of salt exploitation activity, (2) the density of bank intersections, (3) the extent of area covered by Suaeda vera bushes and (4) the structural heterogeneity. The continued management of these salt-pans enhanced bird breeding success. Thus, traditional salt exploitation contributes directly to the conservation of bluethroat, considered as an endangered species in Europe. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Breeding bluethroat; Human activity; Salt-pans area; Landscape heterogeneity; Breeding success 1. Introduction throats. Then, bluethroats decreased and finally dis- appeared with decline of salt extraction and use of The bluethroat (Luscinia svecica) is a migrating pas- banks for crops and pasture. -

Habitats and Species Surveys in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters: Updated October 2016

TOPIC SHEET NUMBER 34 V3 SOUTH RONALDSAY Along the eastern coast of the island at 30m the HABITATS AND SPECIES SURVEYS IN THE PENTLAND videos revealed a seabed of coarse sand and scoured rocky outcrops. The sand was inhabited FIRTH AND ORKNEY WATERS by echinoderms and crustaceans, while the rock was generally bare with sparse Alcyonium digitatum (Dead men’s fi nger) and numerous DUNCANSBY HEAD PAPA WESTRAY WESTRAY Echinus esculentus. Dense brittlestar beds were The seabed recorded to the south of Duncansby SANDAY found to the south. Further north at a depth Head is fl at bedrock with patches of sand, of 50 m the seabed took the form of a mosaic cobbles and boulders. The rock surface is quite ROUSAY MAINLAND STRONSAY of rippled sand, bedrock and boulders with bare other than dense patches of red algae, ORKNEY occasional hydroids and bryozoans. clumps of hydroids and dense brittlestar beds. SCAPA FLOW HOY COPINSAY SOUTH RONALDSAY PENTLAND FIRTH STROMA DUNCANSBY HEAD CAITHNESS VIDEO AND PHOTOGRAPH SITES IN SOUTHERN PART OF ANEMONES URTICINA FELINA ON TIDESWEPT SURVEYED AREA CIRCALITTORAL ROCK Introduction mussels off Copinsay, also found off Noss Head. An extensive coverage of loose-lying Data availability References Marine Scotland Science has been collecting red alga was found in the east of Scapa Flow video and photographic stills from the Pentland The biotope classifi cations and the underlying Moore, C.G. (2009). Preliminary assessment of the on muddy sand and sandeels were also found Firth and Orkney Islands as part of a wider video and images are all available through conservation importance of benthic epifaunal species off west Hoy. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

The Clan Fergusson Or Ferguson

RECORDS OF THE CLAN FERGUSSON OR FERGUSON RECORDS OF THE CLAN AND NAME OF FERGUSSON FERGUSON AND FERGUS SUPPLEMENT Edited for The Clan Fergus(s)on Society by JAMES FERGUSON"' AND ROBERT MENZIES FERGUSSON EDINBURGH: DA YID DOUGLAS 10 CASTLE STREET 1899 All rights resenwl Edinburgh.: Printed by T. an,l A. CoNHTABLE D A V I D D O U G LA S. LONDON . SDIPK1N, 111A3.SHALL1 HA!lflLTO~, KEX'I A!fD CO., L'l'D • .:'IL.\m.ULLAN A::,:J"D BOWES. GLASG 1)W. l!T PREFATORY NOTE AFTER the publication of the Records of the Clan ancl Narne of Fergiisson, Ferguson, and Fergus in 1895, the Editors received a number of communications from persons of the name resident in Canada, the United States, and elsewhere. There also reached them a considerable amount of additional information, illustrating the earlier history of the Clan, and indicating the common origin of various families. The discovery of papers at Pitfour a year after the book came out was followed by the appearance of His Grace the Duke of Atholl's Chronicles of the Fa1nilies of .Atholl and Tulliebardine, which gives many interesting particulars about the Olan in Athole, while the Editors have been placed in communication with the representa tives of other families, who had been unaware of, or omitted to contribute to the original volume. Ultimately in the spring of 1898 the Clan Fergusson Society authorised the preparation and publication of the present supplemen tary volume. The Editors have, as on the previous occasion, en deavoured to supply notices of the families dealt with from the pen of a member of the particular family. -

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (Pspa) NO

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) NO. UK9020318 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge. Scotland 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed and addition of SPA reference Scotland number in preparation for possible formal 30/06/15 consultation. Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Creation of new site selection document. Emma Susie Whiting Philip 17/05/16 Version 4 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Kate Thompson & Emma Philip 17/06/16 Version 5 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 17/6/16 Version 6 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 7 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland, 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Site summary ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Bird survey information ....................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines .................................... 6 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

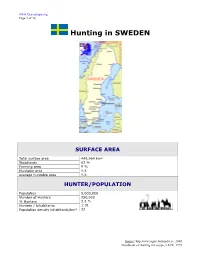

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Records of Species and Subspecies Recorded in Scotland on up to 20 Occasions

Records of species and subspecies recorded in Scotland on up to 20 occasions In 1993 SOC Council delegated to The Scottish Birds Records Committee (SBRC) responsibility for maintaining the Scottish List (list of all species and subspecies of wild birds recorded in Scotland). In turn, SBRC appointed a subcommittee to carry out this function. Current members are Dave Clugston, Ron Forrester, Angus Hogg, Bob McGowan Chris McInerny and Roger Riddington. In 1996, Peter Gordon and David Clugston, on behalf of SBRC, produced a list of records of species recorded in Scotland on up to 5 occasions (Gordon & Clugston 1996). Subsequently, SBRC decided to expand this list to include all acceptable records of species recorded on up to 20 occasions, and to incorporate subspecies with a similar number of records (Andrews & Naylor 2002). The last occasion that a complete list of records appeared in print was in The Birds of Scotland, which included all records up until 2004 (Forrester et al. 2007). During the period from 2002 until 2013, amendments and updates to the list of records appeared regularly as part of SBRC’s Scottish List Subcommittee’s reports in Scottish Birds. Since 2014 these records have appear on the SOC’s website, a significant advantage being that the entire list of all records for such species can be viewed together (Forrester 2014). The Scottish List Subcommittee are now updating the list annually. The current update includes records from the British Birds Rarities Committee’s Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2015 (Hudson 2016) and SBRC’s Report on rare birds in Scotland, 2015 (McGowan & McInerny 2017). -

Territoriality As a Paternity Guard in the European Robin, Erithacus Rubecula

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2000, 60, 165–173 doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1442, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on ARTICLES Territoriality as a paternity guard in the European robin, Erithacus rubecula JOE TOBIAS & NAT SEDDON Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge (Received 29 June 1999; initial acceptance 29 July 1999; final acceptance 18 March 2000; MS. number: 6273) To investigate the relative importance of paternity defences in the European robin we used behavioural observations, simulated intrusions and temporary male removal experiments. Given that paired males did not increase their mate attendance, copulation rate or territory size during the female’s fertile period, the most frequently quoted paternity assurance strategies in birds were absent. However, males with fertile females sang and patrolled their territories more regularly, suggesting that territorial motivation and vigilance were elevated when the risk of cuckoldry was greatest. In addition, there was a significant effect of breeding period on response to simulated intrusions: residents approached and attacked freeze-dried mounts more readily in the fertile period. During 90-min removals of the pair male in the fertile period, neighbours trespassed more frequently relative to prefertile and fertile period controls and appeared to seek copulations with unattended females. When replaced on their territories, males immediately increased both song rate and patrolling rate in comparison with controls. We propose that male robins sing to signal their presence, and increase their territorial vigilance and aggression in the fertile period to protect paternity. 2000 The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour Despite the apparent social monogamy of the majority of Thryothorus nigricapillus: Levin 1996).