Crown of Thecontinent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Report of the Geological Survey for the Calendar Year 1911

5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 SUMMARY REPORT OK THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF MINES FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1914 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT. OTTAWA PRTNTKD BY J. i»k L TAOHE, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT IfAJESTS [No. 26—1915] [No , 15031 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To Field Marshal, Hit Hoi/al Highness Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and of Strath-earn, K.G., K.T., K.P., etc., etc., etc., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Youb Royal Highness.,— The undersigned has the honour to lay before Your Royal Highness— in com- pliance with t>-7 Edward YIT, chapter 29, section IS— the Summary Report of the operations of the Geological Survey during the calendar year 1914. LOUIS CODERRK, Minister of Mines. 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To the Hon. Louis Codebrk, M.P., Minister of Mines, Ottawa. Sir,—I have the honour to transmit, herewith, my summary report of the opera- tions of the Geological Survey for the calendar year 1914, which includes the report* of the various officials on the work accomplished by them. I have the honour to be, sir, Your obedient servant, R. G. MrCOXXFI.L, Deputy Minister, Department of Mines. B . SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 5 GEORGE V. CONTENTS. Paok. 1 DIRECTORS REPORT REPORTS FROM GEOLOGICAL DIVISION Cairncs Yukon : D. D. Exploration in southwestern "" ^ D. MacKenzie '\ Graham island. B.C.: J. M 37 B.C. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003

Intoduction to SNOW PASS - GMC 2003 Welcome to Snow Pass. This is the first GMC to be held at this location, and as far as we can ascertain, you are only the second group to have ever camped amongst this group of lakes. Many GMC’s are situated in valleys; however, this site is unusual as you are on the Continental Divide at an E-W “pass” between the Sullivan and Athabasca rivers, this is the arbitrary division between the Columbia Icefield to the south and the Chaba/Clemenceau Icefields to the north. But, you are also at a N-S pass between the Wales and “Watershed” glaciers, so you are at a “four way intersection” and from Base Camp you can access seven (7) different glacier systems. An intriguing local feature is the snout of the “Watershed” glacier, which actually divides so that it flows both west to join the Wales Glacier and thus drains to the Pacific and also turns east and feeds to the Arctic, which is why it is called the “Watershed” Glacier. In 2003, it may not be too obvious why in 1919 the Alberta/British Columbia Interprovincial Survey called this location “Snow Pass” but in the 1930’s (and even ? the early 1950’s) your Base Camp was still completely ice covered! There was permanent ice/snow from the “Aqueduct” to the “Watershed” to the “Toronto” Glaciers, an area of snow 5 km E-W and 10km N-S. Thus, in 1919, it really was a “snow pass”. See the appended “deglaciation” map. There is a wonderful photograph taken from the summit of Sundial peak in 1919 in the A/BC Volume, p. -

Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park “Work House: Apotoki Oyis - Education for Life” A Glacier National Park Science and Indian Education Program Glacier National Park P.O. Box 128 West Glacier, MT 59936 www.nps.gov/glac/ Produced by the Division of Interpretation and Education Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Revised 2015 Cover Artwork by Chris Daley, St. Ignatius School Student, 1992 This project was made possible thanks to support from the Glacier National Park Conservancy P.O. Box 1696 Columbia Falls, MT 59912 www.glacier.org 2 Education National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the assistance of many people over the past few years. The Appendices contain the original list of contributors from the 1992 edition. Noted here are the teachers and tribal members who participated in multi-day teacher workshops to review the lessons, answer questions about background information and provide additional resources. Tony Incashola (CSKT) pointed me in the right direc- tion for using the St. Mary Visitor Center Exhibit information. Vernon Finley presented training sessions to park staff and assisted with the lan- guage translations. Darnell and Smoky Rides-At-The-Door also conducted trainings for our education staff. Thank you to the seasonal education staff for their patience with my work on this and for their review of the mate- rial. -

Fernie & Elk Valley

Fernie & Elk Valley Cultural Guide Fall 2018 Photo: Matt Glastonbury Matt Photo: | Issue # 9 Issue ELKVALLEYCULTURE.COM | TOURISMFERNIE.COM Fall 2018 | ISSUE #9 A GUIDE TO ARTS, CULTURE AND HERITAGE IN FERNIE & THE ELK VALLEY Featured Events 4 Feature Artist: Joey Kosolofski 7 Fall 2018 Cultural Events 8 Feature Performer: J-Skillz - Jeff Steiert 11 Feature Business: Elk River Apiaries 12 The Arts Station 14 Gallery & Studio Listings 16 Attraction Listings 18 Fernie Museum 20 The Communities Downtown Walking Tour of Fernie 24 of the Elk Valley Fall Iconic Photo Spots 30 In the heart of the majestic Canadian SPARWOOD lies in the middle of Fernie Heritage Library 33 Rocky Mountains, the Elk Valley is a the valley and is the first community The Ktunaxa Nation 34 hidden oasis of verdant landscapes, reached on entering from Alberta. Events In Fernie This Winter 36 charming towns and abundant The town’s name is derived from Built Heritage: The Fernie Cenotaph 38 recreation. For over 100 years, the local trees that were used for pioneers have travelled to the region, manufacturing spars for ocean vessels. NEW - View the Cultural Guide content and past issues online first in search of valuable minerals, and The town was founded as a new home at www.ElkValleyCulture.com now seeking a sanctuary focused on for the residents of the temporary family, community and the beautiful communities of Michel and Natal. outdoors. Mining still forms the base Several art murals can be seen here, of a thriving economy that has now depicting the strong connection to diversified and welcomes a variety of coal mining, with some by Michelle artisans, small businesses, and an active Loughery who was born in the area and year-round recreational and cultural went on to become a world-renowned tourism industry. -

The Leaders, Volume 11 Construction and Engineering Items Appearing in This Magazine Is Reserved

SHARING YOUR VISION. BUILDING SUCCESS. Humber River Hospital, Toronto ON 2015 Dan Schwalm/HDR Architecture, Inc. We are Canada’s construction leaders. We look beyond your immediate needs to see the bigger picture, provide solutions, and ensure that we exceed your expectations. PCL is the proud builder of Canada’s landmark projects. Watch us build at PCL.com Message from Vince Versace, National Managing Editor, ConstructConnect 4 East and West connected by rail 6 On the road: the Trans-Canada Highway – Canada’s main street 21 Chinese workers integral in building Canada’s first megaproject 24 Canada’s most transformational project, the building The CN Tower: Canada’s iconic tower 53 of the Canadian Pacific Railway. From the ground up: building Canada’s parliamentary precinct 56 CanaData Canada’s Economy on Mend, but Don’t Uncork the Champagne Just Yet 14 Fighting the Fiction that Prospects are Nothing but Rosy in Western Canada 26 In Eastern Canada, Quebec is Winning the Accolades 60 Canada’s Top 50 Leaders in Construction 5 Leaders in Construction – Western Canada 28 Leaders in Construction – Eastern Canada 62 Advertisers’ Index 90 www.constructconnect.com Publishers of Daily Commercial News and Journal of Commerce Construction Record 101-4299 Canada Way 3760 14th Avenue, 6th Floor Burnaby, British Columbia Markham, Ontario L3R 3T7 V5G 1H3 Phone: (905) 752-5408 Phone: (604) 433-8164 Fax: (905) 752-5450 Fax: (604) 433-9549 www.dailycommercialnews.com www.journalofcommerce.com CanaData www.canadata.com Mark Casaletto, President John Richardson, Vice President of Customer Relations Peter Rigakos, Vice President of Sales Marg Edwards, Vice President of Content Alex Carrick, Chief Economist, CanaData Vince Versace, National Managing Editor Mary Kikic, Lead Designer Erich Falkenberg, National Production Manager Kristin Cooper, Manager, Data Operations Copyright © 2017 ConstructConnect™. -

Winter 2012 Issue 7

Winter 2012 Issue 7 1 The University of Montana Table of Contents Introduction - Memories of “The Bob” - David Forbes Memories of Royce C. Engstrom 2 President 8 The Rocky Mountain Front - A Profile “The Bob” By Rick and Susie Graetz – The University of Montana Perry Brown By David Forbes 18 Frank F. Liebig - Ranger Flathead National Forest Provost & Vice President for (Retired 1935) Academic Affairs 34 Photographer Spotlight: Tony Bynum James P. Foley Weather Extremes in and around the Crown of the Executive Vice President 48 Continent David Forbes, 49 American Pikas Little Chief Hares of the West interim Vice President for Re- By Allison De Jong search and Creative Scholar- Glacier’s Six 10,000 Foot Summits – The First Ski ship 53 Descent By TRISTAN SCOTT of the Missoulian Christopher Comer Dean, College of Arts & Sci- ences Photo courtesy of David Forbes Editors’ Note: David Forbes, Dean of the Col- Rick Graetz lege of Health Professions and Biomedical Scienc- Initiative Co-Director es at UM, is currently serving as Interim Vice Presi- Geography Faculty dent for Research and Creative Scholarship. Dave has been a great supporter of our Crown of the Photo by - William Klaczynski Jerry Fetz Continent Initiative, and since we were also aware of Initiative Co-Director some of his extensive experiences in several parts of the Crown, particularly in the “Bob,” we asked him if he would Prefessor and Dean Emeritus write up one of the many stories about those experiences and share it with our readers. An experienced horseman College of Arts and Sciences who grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, Dave is not only an exceptional academic administrator and colleague, but an avid outdoorsman who has spent many days and weeks over the past twenty--some years in Montana exploring, in Joe Veltkamp the saddle and on foot, some pretty remote and spectacular parts of the Crown. -

Buffalo in the Mountains: Mapping Evidence of Historical Bison Prescence and Bison Hunting in Glacier National Park

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 Buffalo in the Mountains: Mapping Evidence of Historical Bison Prescence and Bison Hunting in Glacier National Park Kyle Langley University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Folklore Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Langley, Kyle, "Buffalo in the Mountains: Mapping Evidence of Historical Bison Prescence and Bison Hunting in Glacier National Park" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11743. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11743 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO IN THE MOUNTAINS: MAPPING EVIDENCE OF HISTORICAL BISON PRESCENCE AND BISON HUNTING IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By KYLE STUART LANGLEY B.A. in History and Anthropology, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, 2011 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Cultural Heritage Option The University of Montana Missoula, MT April 2021 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Kelly Dixon, Chair Anthropology Dr. Greg Campbell Anthropology Dr. Jedediah Brodie Biological Sciences & Wildlife Biology Aaron Brien, M.A. -

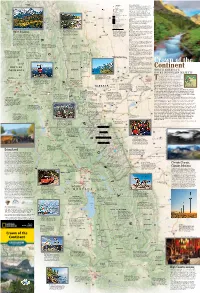

R O C K Y M O U N T a I

KOOTENAY 115° 114°W Map Key What Is Geotourism All About? NATIONAL According to National Geographic, geotourism “sustains or enhances Community PARK the geographical character of a place—its environment, culture, Museum aesthetics, heritage, and the well-being of its residents.” Geotravelers, To Natural or scenic area then, are people who like that idea, who enjoy authentic sense of Calgary place and care about maintaining it. They find that relaxing and Other point of interest E having fun gets better—provides a richer experience—when they get E Black Diamond Outdoor experience involved in the place and learn about what goes on there. BOB CREEK WILDLAND, AB ALBERTA PARKS Turner Geotravelers soak up local culture, hire local guides, buy local Valley World Heritage site C Radium l foods, protect the environment, and take pride in discovering and EHot Springs os Scenic route ed observing local customs. Travel-spending choices can help or hurt, so i n 22 National Wild and Scenic River geotravelers patronize establishments that care about conservation, BARING CREEK IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, MT CHUCKHANEY.COM wi nt er Urban area preservation, beautification, and benefits to local people. 543 Learn more at crownofthecontinent.natgeotourism.com. Columbia High River E 23 Protected Areas Wetlands Indian or First Nation reserve Geotraveler Tips: Buy Local 93 541 National forest or reserve High C w Patronize businesses that support the community and its conservation O Frank 40 oo KMt. Joffre N d Longview Lake National park and preservation efforts. Seek out local products, foods, services, and T E 11250 ft I E ELK N 3429 m E Longview Jerky Shop shops. -

Scenic Features, 1914

ORIGIN OF THE SCENIC FEATURES ' OF THE GLACIER NATIONAL PARK DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY ) 9)4 For sale by Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington. D. C. Price ) 5 cents ~J ORIGIN OF THE SCENIC FEATURES OF THE GLACIER NATIONAL PARK. By MARlUil R. CAMPBELL, Geologist. United Stale8 Geological S11rvey. INTRODUCTION. The Glacier National Park comprises an area of about 1,400 square miles in the northern Rocky Mountains, extending from the Great Northern Railway on the south to the Canadian line on the north and from the Great Plains on the east to Flathead River 1 on the west. Formerly this was a region visited by few except hunters in search of big game, and by prospectors eager to secure the stores of copper that were supposed to be contained in its mounta;n fastnesses. The ADDITIONAL COPIES dreams of mineral wealth, however, proved to be fallacious, and by OF THIS PUBLICATION :MAY BE PROCURED FROM TH.E SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUlfENTS act of Congress, May 11, 1910, it was created a national park in order GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 'VASHlNGTON, D. C. to preserve for all time and for all generations its mountain beauties . AT In general, the national parks so far created h ave been set aside and 15 CENTS PER COPY dedicated as playgrounds for the people, because they contain striking examples of nature'$ handiwork, such as the geysers and hot springs of the Yellowstone, the wonderful valleys, great granite walls, and cascades of the Yosemite, and the results of volcanic activity as exhibited in Crater Lake and the beautiful cone of Mount Rainier. -

Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains by Tarissa L

Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Spoonhunter, Tarissa L. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 07:16:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/323418 Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains by Tarissa L. Spoonhunter __________________________ Copyright © Tarissa Spoonhunter 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains Spoonhunter2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Tarissa Spoonhunter, titled Blackfoot Confederacy Keepers of the Rocky Mountains and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Benedict Colombi Date: May 5, 2014 Eileen Luna-Firebaugh Date: May 5, 2014 Manley Begay Date: May 5, 2015 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

FINAL Cover Mexoverview 2004

British Columbia Mines & Mineral Exploration Overview 2004 Ministry of Energy and Mines - Information Circular 2005-1 BRITISH COLUMBIA MINING AND MINERAL EXPLORATION OVERVIEW 2004 Ministry of Energy and Mines Tom Schroeter, PEng/PGeo; Michael Cathro, PGeo; David Grieve, PGeo; Robert Lane, PGeo; Jamie Pardy, PGeo; Barry Ryan, PGeo; George Simandl, PGeo; and Paul Wojdak, PGeo INTRODUCTION coal. For example, gold reached a 16-year high of over US$450 per ounce in early December. Mineral British Columbia’s mineral resources are strategically exploration expenditures increased to their highest level located to play a role in the international mining industry, since 1991 and are estimated at $120 to $130 million for particularly for North American and Asian markets. The 2004 (Figure 1). The number of new mineral claim units province has a well-defined potential for a wide variety of recorded in 2004 is 47 232, an increase of 30% from the minerals and deposit types. The geoscience database is previous year (Figure 2). The number of total mineral extensive and easily accessed and the provincial units in good standing as of January 1, 2005 was 184 464, government is committed to aggressively improving that up about 18% from 2003. The number of forfeited units in data and encouraging new developments. With attractive 2004 was 12 209, down 10% from 2003. This is the fifth energy costs, a well-developed, all-weather highway year in a row that there has been an increase in new system, rail links and a number of deep-water ports, mineral units recorded and a decrease in forfeited claims, British Columbia has the infrastructure to get coal, another indicator of sustained and growing interest in the minerals and resulting products to markets.