The Status of Voucher Specimens of Mushroom Species Thought to Be Extinct from Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultivation of the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Sp.) on Wood Substrates in Hawaii

CULTIVATION OF THE OYSTER MUSHROOM (PLEUROTUS SP.) ON WOOD SUBSTRATES IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'IIN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TROPICAL PLANT AND SOIL SCIENCE DECEMBER 2004 By Tracy E. Tisdale Thesis Committee: Susan C. Miyasaka, Chairperson Mitiku Habte Don Hemmes Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge Susan C. Miyasaka, my major advisor, for her generosity, thoughtfulness, patience and infinite support throughout this project. I'd like to thank Don Hemmes and Mitiku Habte for taking time out of their schedules to serve on my committee and offer valuable insight. Thanks to Jim Hollyer for the much needed advising he provided on the economic aspect of this project. Thanks also to J.B. Friday, Bernie Kratky and all the smiling faces at Beaumont, Komohana, Waiakea and Volcano Research Stations who provided constant encouragement and delight throughout my mushroom growing days in Hilo. 111 Table of Contents Acknowledgements , iii List of Tables ,,, , vi List of Figures vii Chapter 1: Introduction '" 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review , 3 Industry ,,.. ,,,,, , 3 Substrates 6 Oyster Mushroom " '" 19 Production Overview 24 Chapter 3: Research Objectives , '" 32 Chapter 4: Materials and Methods 33 Substrate Wood 33 Cultivation Methods 34 Crop Yield ,, 39 Nutrients 43 Taste 44 Fruiting Site Assessment. .46 Economic Analysis .46 Chapter 5: Results and Discussion ,, .48 Substrate Wood ,, 48 Preliminary Experiment. '" 52 IV Final Experiment. -

Appendix K. Survey and Manage Species Persistence Evaluation

Appendix K. Survey and Manage Species Persistence Evaluation Establishment of the 95-foot wide construction corridor and TEWAs would likely remove individuals of H. caeruleus and modify microclimate conditions around individuals that are not removed. The removal of forests and host trees and disturbance to soil could negatively affect H. caeruleus in adjacent areas by removing its habitat, disturbing the roots of host trees, and affecting its mycorrhizal association with the trees, potentially affecting site persistence. Restored portions of the corridor and TEWAs would be dominated by early seral vegetation for approximately 30 years, which would result in long-term changes to habitat conditions. A 30-foot wide portion of the corridor would be maintained in low-growing vegetation for pipeline maintenance and would not provide habitat for the species during the life of the project. Hygrophorus caeruleus is not likely to persist at one of the sites in the project area because of the extent of impacts and the proximity of the recorded observation to the corridor. Hygrophorus caeruleus is likely to persist at the remaining three sites in the project area (MP 168.8 and MP 172.4 (north), and MP 172.5-172.7) because the majority of observations within the sites are more than 90 feet from the corridor, where direct effects are not anticipated and indirect effects are unlikely. The site at MP 168.8 is in a forested area on an east-facing slope, and a paved road occurs through the southeast part of the site. Four out of five observations are more than 90 feet southwest of the corridor and are not likely to be directly or indirectly affected by the PCGP Project based on the distance from the corridor, extent of forests surrounding the observations, and proximity to an existing open corridor (the road), indicating the species is likely resilient to edge- related effects at the site. -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Elias Fries – En Produktiv Vetenskapsman Redan Som Tonåring Började Fries Att Skriva Uppsatser Om Naturen

Elias Fries – en produktiv vetenskapsman Redan som tonåring började Fries att skriva uppsatser om naturen. År 1811, då han fyllt 17 år, fick han sina första alster publi- cerade. Samma år påbörjade han universitetsstudier i Lund och tre år senare var han klar med sin magisterexamen. Därefter Elias Fries – ein produktiver Wissenschaftler följde inte mindre än 64 aktiva år som mykolog, botanist, filosof, lärare, riksdagsman och akademiledamot. Han var oerhört produktiv och författade inte bara stora och betydande böcker i mykologi och botanik utan också hundratals mindre artiklar och uppsatser. Dessutom ledde han ett omfattande arbete med att avbilda svampar. Dessa målningar utgavs som planscher och Bereits als Teenager begann Fries Aufsätze dem schrieb er Tagebücher und die „Tidningar i Na- Die Zeit in Uppsala – weitere 40 Jahre im das führte zu sehr erfolgreichen Ausgaben seiner und schrieb: „In Gleichheit mit allem dem das sich aus Auch der Sohn Elias Petrus, geboren im Jahre 1834, und Seth Lundell (Sammlungen in Uppsala), Fredrik über die Natur zu schreiben. Im Jahre 1811, turalhistorien“ (Neuigkeiten in der Naturalgeschich- Dienste der Mykologie Werke. Das erste, „Sveriges ätliga och giftiga svam- edlen Naturtrieben entwickelt, erfordert das Entstehen war ein begeisterter Botaniker und Mykologe. Leider Hård av Segerstad (publizierte 1924 eine Überarbei- te) mit Artikeln über beispielsweise seltene Pilze, Auch nach seinem Umzug nach Uppsala im Jahre par“ (Schwedens essbare und giftige Pilze), war ein dieser Liebe zur Natur ernste Bemühungen, aber es verstarb er schon in jungen Jahren. Ein dritter Sohn, tung von Fries’ Aufzeichnungen), Meinhard Moser bidrog till att kunskap om svamp spreds. Efter honom har givetvis det vetenskapliga arbetet utvecklats vidare men än idag an- in seinem 18. -

MYCOTAXON Volume 96, Pp

MYCOTAXON Volume 96, pp. 181–191 April–June 2006 The genus Chlorophyllum (Basidiomycetes) in China Z. W. GE1, 2 & Zhu L. YANG1, * [email protected] [email protected] 1 Laboratory of Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany Chinese Academy of Sciences, Heilongtan, Kunming 650204, Yunnan, P. R. China 2 Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100039, P. R. China Abstract—Species of the genus Chlorophyllum (Agaricaceae) in China are described and illustrated with line drawings. Among them, C. sphaerosporum is new to science, and C. hortense is new to China. A key to the Chlorophyllum species in China is also provided. Key words—Agaricales, new taxon, new record, taxonomy, distribution Introduction The genus Chlorophyllum Massee (Agaricaceae, Agaricales, Basidiomycetes) in its amended sense is characterized by a hymenidermal pileus covering, a smooth stipe, and basidiospores without a germ pore or with a germ pore but just caused by a depression in the episporium. A hyaline covering on the germ pore is absent. The basidiospores may be white, green, brownish or brown in deposit, and the habit varies from agaricoid to secotioid (Vellinga 2001, 2002, 2003a, b; Vellinga & de Kok 2002; Vellinga et al. 2003). During our survey of the lepiotoid fungi in China, several species were identified, and one new species of the genus was encountered and thus described below. Differences between similar species are provided and discussed. Material and methods All material examined collected in China, and deposited in three Herbaria. Herbarium codes used follow Holmgren et al. (1990) with one exception: HKAS = Herbarium of Cryptogams, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, which is not listed in the index or relevant publications. -

Title of Manuscript

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 7(1): 8–18 (2017) ISSN 2229-2225 www.creamjournal.org Article Doi 10.5943/cream/7/1/2 Copyright © Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences Eco-diversity, productivity and distribution frequency of mushrooms in Gurguripal Eco-forest, Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal, India Krishanu Singha, Amrita Banerjee, Bikash Ranjan Pati, Pradeep Kumar Das Mohapatra* Department of Microbiology, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore – 721 102, West Bengal, India Singha K, Banerjee A, Pati BR, Das Mohapatra PK 2017 – Eco-diversity, productivity and distribution frequency of mushrooms in Gurguripal Eco-forest, Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal, India. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 7(1), 8–18, Doi 10.5943/cream/7/1/2 Abstract Gurguripal is a forest based rural area situated in Paschim Medinipur District, West Bengal, India. It is located at 22°25" - 35°8"N latitude and 87°13" - 42°4"E longitude, having an altitude about 60 M. This area represents tropical evergreen and deciduous mixed type of forest dominated mainly by „Sal‟. The present study deals with the status of mushroom diversity and productivity in Gurguripal Eco-forest. Field survey has been conducted from May 2014 to October 2015 and a total of 71 mushroom species of 41 genera belonging to 24 families were recorded including 32 edible, 39 inedible and altogether 19 medicinally potential mushrooms. The genus Russula exhibited the maximum number of species and the family Tricholomataceae represented the maximum number of individuals. According to Simpson‟s index of diversity, the calculated value of species richness was 0.92 and as to Shannon‟s diversity index, the relative abundance of species was found to be 2.206. -

The Diversity of Basidiomycota Fungi That Have the Potential As a Source of Nutraceutical to Be Developed in the Concept of Integrated Forest Management Poisons

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-2S, July 2019 The Diversity of Basidiomycota Fungi that Have the Potential as a Source of Nutraceutical to be Developed in the Concept of Integrated Forest Management Mustika Dewi, I Nyoman Pugeg Aryantha, Mamat Kandar straw mushrooms, oyster mushrooms, and shiitake Abstract: The fungus Basidiomycota found in Indonesia have mushrooms. very high diversity, but have not been explored so far. The development of local Basidiomycota mushrooms that Development of fungi Basidiomycota is an alternative as a are cultivated by utilizing space on the forest floor has not source of natural nutraceuticals, especially beta glucan and been done mostly in Indonesia. In several countries such as lovastatin compounds. This compound can be used in the pharmaceutical and food fields. This study aims to obtain Japan, people have long been cultivating shitake mushrooms Basidiomycota fungi isolates that have the potential as a by utilizing forest floors. Reported by (Savoie & Largeteau, nutraceutical source. As the first stage in this research, the 2011) that mushrooms from the Basidiomycota group are activities carried out were exploration, isolation on culture widely produced in forest areas through the utilization of media, and identification of fungi based on genotypic forest floors as a place to grow these fungi which have characters. The results showed that the fungi identified based on economic value quite high by applying the concept of their genotypic characters were Pleurotusostreatus, Ganodermacf, Resinaceum, Lentinulaedodes, micosilviculture. The concept of micosilviculture is a Vanderbyliafraxinea, Auricularia delicate, Pleurotusgiganteus, concept that is applied in the management of integrated Auricularia sp. -

The Genus Pluteus (Basidiomycota, Agaricales, Pluteaceae) from Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa

Mycosphere 9(3): 598–617 (2018) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/9/3/10 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences The genus Pluteus (Basidiomycota, Agaricales, Pluteaceae) from Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa Desjardin DE1 and Perry BA2 1Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Ave., San Francisco, California 94132, USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State University East Bay, 25800 Carlos Bee Blvd., Hayward, California 94542, USA Desjardin DE, Perry BA 2018 – The genus Pluteus (Basidiomycota, Agaricales, Pluteaceae) from Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. Mycosphere 9(3), 598–617, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/9/3/10 Abstract Six species of Pluteus are reported from the African island nation, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe. Two represent new species (P. hirtellus, P. thomensis) and the other four represent new distribution records. Comprehensive descriptions, line drawings, colour photographs, comparisons with allied taxa, a dichotomous key to aid identification, and a phylogenetic analysis of pertinent Pluteus species based on ITS rDNA sequence data are provided. Key words – 2 new species – fungal diversity – Gulf of Guinea – mushrooms – pluteoid fungi – taxonomy Introduction In April 2006 (2 weeks) and April 2008 (3 weeks), expeditions led by scientists from the California Academy of Sciences and joined by mycologists from San Francisco State University visited the West African islands of São Tomé and Príncipe to document the diversity of plants, amphibians, marine invertebrates and macrofungi. This is the sixth in a series of papers focused on documenting the basidiomycetous macrofungi from the Republic (Desjardin & Perry 2009, 2015a, b, 2016, 2017). -

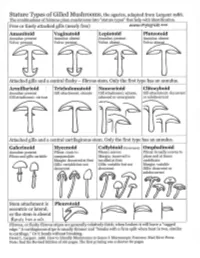

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

Pleurotus, and Tremella

J, Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology Research Copy rights@ Waill A. Elkhateeb et.al. AUCTORES Journal of Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology Research Waill A. Elkhateeb * Globalize your Research Open Access Research Article Mycotherapy of the good and the tasty medicinal mushrooms Lentinus, Pleurotus, and Tremella Waill A. Elkhateeb1* and Ghoson M. Daba1 1 Chemistry of Natural and Microbial Products Department, Pharmaceutical Industries Division, National Research Centre, Dokki, Giza, 12622, Egypt. *Corresponding Author: Waill A. Elkhateeb, Chemistry of Natural and Microbial Products Department, Pharmaceutical Industries Division, National Research Centre, Dokki, Giza, 12622, Egypt. Received date: February 13, 2020; Accepted date: February 26, 2021; Published date: March 06, 2021 Citation: Waill A. Elkhateeb and Ghoson M. Daba (2021) Mycotherapy of the good and the tasty medicinal mushrooms Lentinus, Pleurotus, and Tremella J. Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology Research. 4(2); DOI: 10.31579/2693-7247/29 Copyright: © 2021, Waill A. Elkhateeb, This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Fungi generally and mushrooms secondary metabolites specifically represent future factories and potent biotechnological tools for the production of bioactive natural substances, which could extend the healthy life of humanity. The application of microbial secondary metabolites in general and mushrooms metabolites in particular in various fields of biotechnology has attracted the interests of many researchers. This review focused on Lentinus, Pleurotus, and Tremella as a model of edible mushrooms rich in therapeutic agents that have known medicinal applications. Keyword: lentinus; pleurotus; tremella; biological activities Introduction of several diseases such as cancer, hypertension, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and others [14, 15].