Colorado Magazine Fall 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Report

FOR RELEASE: THURSDAY, JANUARY 11, 2001, 4:00 P.M. It’s the Economy Again! CLINTON NOSTALGIA SETS IN, BUSH REACTION MIXED Also Inside ... w Hillary's Favorability Rises. w Winners and Losers under Bush. w Powell a Visible Choice. w Clinton's Issue Report Card. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Andrew Kohut, Director Carroll Doherty, Editor Kimberly Parker, Research Director Michael Dimock, Survey Director Nilanthi Samaranayake, Project Director Pew Research Center for The People & The Press 202/293-3126 http://www.people-press.org It’s the Economy Again! CLINTON NOSTALGIA SETS IN, BUSH REACTION MIXED As the country awaits the formal transfer of presidential power, Bill Clinton has never looked better to the American public, while his successor George W. Bush is receiving initial reviews that are more mixed, though still positive. The president leaves office with 61% of the public approving of the way he is handling the job, combined with a surprisingly lofty 64% favorability rating (up from 48% in May 2000). The favorability rating, a mixture of personal and performance evaluations, is all the more impressive because such judgments have never been Clinton’s strong suit. Unlike other recent presidents, Clinton’s ratings have often run below his job approval scores. As historians and scholars render their judgments of Clinton’s legacy, the public is Improved Opinion of the Clintons ... weighing in with a nuanced verdict. By a 60%- Aug May Jan 27% margin, people feel that, in the long run, 1998 2000 2001 Clinton’s accomplishments in office will Bill Clinton ... %%% Favorable 54 48 64 outweigh his failures, even though 67% think he Unfavorable 44 47 34 will be remembered for impeachment and the Don't know 2 5 2 100 100 100 scandals, not for what he achieved. -

Name Address City State ZIP Web Site Benefits

Name Address City State ZIP Web Site Benefits Berman Museum of World History 840 Museum Dr. Anniston Alabama 36206 www.bermanmuseum.org (D) - Discounted Admission Arizona Historical Society - Arizona History Museum 949 E. 2nd St. Tucson Arizona 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Arizona Historical Society - Downtown History Museum 140 N. Stone Ave. Tuscon Arizona 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Arizona Historical Society - Fort Lowell Museum 2900 N. Craycroft Rd. Tuscon Arizona 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Arizona Historical Society - Pioneer Museum 2340 N. Fort Valley Rd. Flagstaff Arizona 86001 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Arizona Historical Society - Sanguinetti House Museum 240 S. Madison Ave. Yuma Arizona 85364 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Arizona Historical Society Museum at Papago Park 1300 N. College Ave. Tempe Arizona 85281 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) - Discounted Admission ($1.00 off Admission) Gila County Historical Museum 1330 N. Broad St. Globe Arizona 85501 www.gilahistorical.com (F, T, P) - Free Admission; Free or Discounted Tour(s); Free Parking Show Low Historical Museum 561 E. Deuce of Clubs, PO Box 3468 Show Low Arizona 85902 www.showlowmuseum.com (F, G) - Free Admission; Gift Shop Discount The Jewish History Museum 564 S. Stone Ave. Tucson Arizona 85702 www.jewishhistorymuseum.org (F) - Free Admission Historic Arkansas Museum 200 E. Third St. Little Rock Arkansas 72201 www.historicarkansas.org (F, P, G) - Free Admission; Free Parking; Gift Shop Discount Old Independence Regional Museum 380 South Ninth St. -

Time Travelers

Sioux City Museum & Historical Association Members Your membership card is your passport to great Benefits Key: benefits at any participating Time Travelers C = Complimentary or discounted museum publication, gift or service museum or historic site across the country! D = Discounted admission P = Free parking F = Free admission R = Restaurant discount or offer Please note: Participating institutions are constantly G = Gift shop discount or offer S = Discounted special events O = Does not normally charge admission T = Free or discounted tour changing so calling ahead to confirm the discount is highly recommended. CANADA The Walt Disney Family Museum Georgia Indiana TIFF • (888)599-8433 San Francisco, CA • (415)345-6800 • Benefits: F American Baptist Historical Soc. • (678)547-6680 Barker Mansion Civic Center • (219) 873-1520 Toronto, ON • Benefits: C • tiff.net waltdisney.org Atlanta, GA • Benefits: C • abhsarchives.org Michigan, IN • Benefits: F T • barkermansion.com Twentynine Palms Historical Society Atlanta History Center • (404)814-4100 Brown County History Center USA Twentynine Palms • (760)367-2366 • Benefits: G Atlanta, GA • Benefits: F • atlantahistorycenter.com Nashville, IN • (812)988-2899 • Benefits: D G Alabama 29palmshistorical.com Augusta Museum of History • (706)722-8454 browncountyhistorycenter.org Berman Museum of World History USS Hornet Museum • (510)521-8448 Augusta, GA • Benefits: F G • augustamuseum.org Carnegie Center for Art & History Anniston, AL • (256)237-6261 • Benefits: D Alameda, CA • Benefits: D • uss-hornet.org -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Lonely Sentinel

Lonely Sentinel Fort Aubrey and the Defense of the Kansas Frontier, 1864-1866 Defending the Fort: Indians attack a U.S. Cavalry post in the 1870s (colour litho), Schreyvogel, Charles (1861-1912) / Private Collection / Peter Newark Military Pictures / Bridgeman Images Darren L. Ivey History 533: Lost Kansas Communities Chapman Center for Rural Studies Kansas State University Dr. M. J. Morgan Fall 2015 This study examines Fort Aubrey, a Civil War-era frontier post in Syracuse Township, Hamilton County, and the men who served there. The findings are based upon government and archival documents, newspaper and magazine articles, personal reminiscences, and numerous survey works written on the subjects of the United States Army and the American frontier. Map of Kansas featuring towns, forts, trails, and landmarks. SOURCE: Kansas Historical Society. Note: This 1939 map was created by George Allen Root and later reproduced by the Kansas Turnpike Authority. The original drawing was compiled by Root and delineated by W. M. Hutchinson using information provided by the Kansas Historical Society. Introduction By the summer of 1864, Americans had been killing each other on an epic scale for three years. As the country tore itself apart in a “great civil war,” momentous battles were being waged at Mansfield, Atlanta, Cold Harbor, and a host of other locations. These killing grounds would become etched in history for their tales of bravery and sacrifice, but, in the West, there were only sporadic clashes between Federal and Confederate forces. Encounters at Valverde in New Mexico Territory, Mine Creek in Linn County, Kansas, and Sabine Pass in Texas were the exception rather than the norm. -

150923Timetravelerslist.Pdf

Benefits Key: G- Gift Shop Discount It is highly recommended to C- Free or Discounted Gift, P- Free Parking call ahead and do your own Publication, or Service R- Restaurant Discount D- Discounted Admission S- Special Event Offer independent research on any F- Free Admission T- Free or Discounted Tour(s) institution you plan to visit. Name Address City, State Zip Website Benefit Alabama Berman Museum of World History 840 Museum Dr. Anniston, AL 36206 www.bermanmuseum.org/ (D) Alaska Arizona Arizona Historical Society - Arizona History Museum 949 E. 2nd St. Tucson, AZ 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Arizona Historical Society - Downtown History Museum 140 N. Stone Ave. Tuscon, AZ 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Arizona Historical Society - Fort Lowell Museum 2900 N. Craycroft Rd. Tuscon, AZ 85719 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Arizona Historical Society - Pioneer Museum 2340 N. Fort Valley Rd. Flagstaff, AZ 86001 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Arizona Historical Society - Sanguinetti House Museum 240 S. Madison Ave. Yuma, AZ 85364 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Arizona Historical Society Museum at Papago Park 1300 N. College Ave. Tempe, AZ 85281 www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org (D) Gila County Historical Museum 1330 N. Broad St. Globe, AZ 85501 www.gilahistorical.com (F, T, P) Show Low Historical Museum 561 E. Deuce of Clubs Show Low, AZ 85902 www.showlowmuseum.com (F, G) The Jewish History Museum 564 S. Stone Ave. Tucson, AZ 85702 www.jewishhistorymuseum.org (F) Arkansas Historic Arkansas Museum 200 E. Third St. Little Rock, AR 72201 www.historicarkansas.org (F, P, G) Old Independence Regional Museum 380 South Ninth St. -

Pdf-USFWS NEWS

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Fish & Wildlife News National Wildlife Refuge System Centennial Special Edition Spring 2003 Prelude . 1 Table of Director’s Corner: Looking Back, Looking Forward . 2 System of Lands for Wildlife and People for Today and Tomorrow . 3 Contents Future of the Refuge System. 4 Fulfilling the Promise for One Hundred Years . 5 Keeping the Service in the Fish & Wildlife Service . 6 Past . 8 Timeline of Refuge Creation . 9 Shaping the NWRS: 100 Years of History The First 75 Years: A Varied and Colorful History . 12 The Last 25 Years: Our Refuge System . 16 The First Refuge Manager . 18 Pelican Island’s First Survey. 21 CCC Had Profound Effect on Refuge System . 22 Refuge Pioneer: Tom Atkeson . 23 From Air Boats to Rain Gauges . 23 A Refuge Hero Called “Mr. Conservation” . 24 Programs . 25 The Duck Stamp: It’s Not Just for Hunters––Refuges Benefit Too 26 Caught in a Web and Glad of It. 27 Aquatic Resources Conservation on Refuges . 28 To Conserve and Protect: Law Enforcement on Refuges . 29 Jewels of the Prairie Shine Like Diamonds in the Refuge System Crown . 30 Untrammeled by Man . 31 Ambassadors to Alaska: The Refuge Information Technicians Program . 32 Realty’s Role: Adding to the NWRS . 34 Safe Havens for Endangered Species. 34 The Lasting Legacy of Three Fallen Firefighters: Origins of Professional Firefighting in the Refuge System . 35 Part Boot Camp: Part Love-In . 36 Sanctuary and Stewardship for Employees. 37 How a Big, Foreign-Born Rat Came to Personify a Wildlife Refuge Battle with Aquatic Nuisance Species . -

2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude

Photo: VISIT DENVER MPMA Regional Museum Conference 64th Annual MPMA Conference October 15 - October 19 | Denver, CO Photo: ToddPowell Photo Credit VISITDENVER 2017 Preliminary Conference Program Photo: VISIT DENVER Western Altitude / Western Attitude Photo: VISIT DENVER Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Western Altitude / Western Attitude Join in the conversation: #MPMA2017 Why Museums Are Needed Now More Than Ever Photo: VISIT DENVER/Steve Crecelius Invitation from the MPMA Conference Chairs Dear Colleagues and Friends: Join us this fall in Denver, Colorado…where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains. What an appropriate place for the 2017 annual meeting of the Mountain-Plains Museums Association (MPMA), an organization where the museums of the mountains and plains come together. And MPMA even had its origins in this area. Here you will discover Western Altitudes and Western Attitude at our museums, historic sites, and within our people. John Deutschendorf was so impressed by Denver that he took it as his last name, becoming one of Colorado’s beloved balladeers, singing about our altitudes and our attitudes. John Denver wasn’t alone in his attraction to the area; millions have been rushing to the state since gold was discovered in 1859. What you will discover during our conference is that Denver is not just a single city but an entire region offering many great cultural resources as well as great scenic beauty. Our evening events will capitalize on the best that the Denver area has to offer. The opening event will be hosted in the heart of Denver by History Colorado, site of exhibits about Colorado’s history (including “Backstory: Western American Art in Context,” an exciting collaboration with the Denver Art Museum), and by the Clyfford Still Museum, where the works and life of one of the fathers of abstract expressionism are exhibited. -

Public Danger

DAWSON.36.6.4 (Do Not Delete) 8/19/2015 9:43 AM PUBLIC DANGER James Dawson† This Article provides the first account of the term “public danger,” which appears in the Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Drawing on historical records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Article argues that the proper reading of “public danger” is a broad one. On this theory, “public danger” includes not just impending enemy invasions, but also a host of less serious threats (such as plagues, financial panics, jailbreaks, and natural disasters). This broad reading is supported by constitutional history. In 1789, the first Congress rejected a proposal that would have replaced the phrase “public danger” in the proposed text of the Fifth Amendment with the narrower term “foreign invasion.” The logical inference is that Congress preferred a broad exception to the Fifth Amendment that would subject militiamen to military jurisdiction when they were called out to perform nonmilitary tasks such as quelling riots or restoring order in the wake of a natural disaster—both of which were “public dangers” commonly handled by the militia in the early days of the Republic. Several other tools of interpretation—such as an intratextual analysis of the Constitution and an appeal to uses of the “public danger” concept outside the Fifth Amendment—also counsel in favor of an expansive understanding of “public danger.” The Article then unpacks the practical implications of this reading. First, the fact that the Constitution expressly contemplates “public danger” as a gray area between war and peace is itself an important and unexplored insight. -

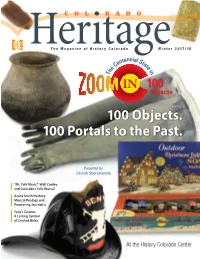

100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past

The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 100 Objects. 100 Portals to the Past. Presented by Colorado State University “Mr. Folk Music”: Walt Conley and Colorado’s Folk Revival Azalia Smith Hackley: Musical Prodigy and Pioneering Journalist Tony’s Conoco: A Lasting Symbol of Crested Butte At the History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor Micaela Cruce Editorial Assistance Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer The Magazine of History Colorado Winter 2017/18 Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services How Did We Become Colorado? 4 Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by The artifacts in Zoom In serve as portals to the past. History Colorado, contains articles of broad general By Julie Peterson and educational interest that link the present to the 8 Azalia Smith Hackley past. Heritage is distributed quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of A musical prodigy made her name as a journalist and activist. higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented when By Ann Sneesby-Koch submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 16 “Mr. Folk Music” office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Walt Conley headlined the Colorado folk-music revival. Publications office. History Colorado disclaims By Rose Campbell responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado also publishes 24 Tony’s Conoco Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, events, A symbol of Crested Butte embodies memories and more. and exhibition listings. By Megan Eflin Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a benefit of membership. -

Colorado Women Take Center Stage

January/February 2020 Colorado Women Take Center Stage At the Center for Colorado Women’s History and Our Other Sites Interactives in What’s Your Story? help you find your superpower, like those of 101 influential Coloradans before you. Denver / History Colorado Center 1200 Broadway. 303/HISTORY, HistoryColoradoCenter.org ON VIEW NOW A Legacy of Healing: Jewish Leadership in Colorado’s Health Care Ballantine Gallery Sunlight, dry climate, high altitude, nutritious food, fresh air—that was the prescription for treating tuberculosis. As thousands flocked to Colorado for a cure, the Jewish community led the way in treatment. Co-curated by Dr. Jeanne Abrams from the University of Denver Libraries’ Beck Archives, A Legacy of Healing tells the story of the Jewish community’s involvement in revolutionizing our state’s health care in the late 19th and early 20th century. See rare film footage, medical tools and photographs from the top-tier Denver tuberculosis hospitals. Journey through the stories of Jewish leaders and ordinary citizens committed to caring for those in need. A Legacy of Healing honors the Jewish community for providing care to all Coloradans regardless of faith, race or social standing. NEW NEW & VIEW ON A Legacy of Healing is made possible through Rose Medical Center, the Chai (LIFE) Presenting Sponsor. The Education Sponsor is Rose Community Foundation. National Jewish Health, Mitzvah (Act of Kindness) Sponsor. ON VIEW NOW What’s Your Story? Owens Hickenlooper Leadership Gallery What’s your superpower? Is it curiosity—like the eleven-year-old who invented a way to test water for lead? Is it determination—like the first woman to work in the Eisenhower Tunnel? Generations have used their powers for good to create a state where values like innovation, collaboration and stewardship are celebrated. -

Labor History Timeline

Timeline of Labor History With thanks to The University of Hawaii’s Center for Labor Education and Research for their labor history timeline. v1 – 09/2011 1648 Shoemakers and coopers (barrel-makers) guilds organized in Boston. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu. Image:http://mattocks3.wordpress.com/category/mattocks/james-mattocks-mattocks-2/ Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1776 Declaration of Independence signed in Carpenter's Hall. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image:blog.pactecinc.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1790 First textile mill, built in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was staffed entirely by children under the age of 12. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image: creepychusetts.blogspot.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1845 The Female Labor Reform Association was created in Lowell, Massachusetts by Sarah Bagley, and other women cotton mill workers, to reduce the work day from 12-13 hours to10 hours, and to improve sanitation and safety in the mills. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: historymartinez.wordpress.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1868 The first 8-hour workday for federal workers took effect. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: From Melbourne, Australia campaign but found at ntui.org.in Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1881 In Atlanta, Georgia, 3,000 Black women laundry workers staged one of the largest and most effective strikes in the history of the south. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu, Image:http://www.apwu.org/laborhistory/10-1_atlantawomen/10-1_atlantawomen.htm Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1886 • March - 200,000 workers went on strike against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific railroads owned by Jay Gould, one of the more flamboyant of the 'robber baron' industrialists of the day.