Unreported Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Law School Experience, Part I

MARCH 2020 • $5 A Publication of the San Fernando Valley Bar Association The Law School Experience, Part I Contract Terms: What They Are and How They Work www.sfvba.org www.ketkcpa.com 2 Valley Lawyer ■ MARCH 2020 www.sfvba.org lewitthackman.com 818.990.2120 www.sfvba.org MARCH 2020 ■ Valley Lawyer 3 CONTENTS MARCH 2020 VALLEY AWYER A Publication of the San Fernando Valley Bar Association 12 22 36 30 FEATURES 12 Contract Terms: What They Are and How DEPARTMENTS They Work | BY DAVID GURNICK MCLE TEST NO. 137 ON PAGE 21. 7 President’s Message 22 The Law School Experience, Part I: 9 Editor’s Desk The Deans’ Perspective | BY MICHAEL D. WHITE 10 Event Calendars 30 A Look Back, A Look Forward | BY KYLE M. ELLIS 33 New Members 35 Member Focus 36 Promoting the Law Firm: What Works | BY SETH HOROWITZ 41 Attorney Referral Service COLUMN 43 Photo Gallery 44 Dear Phil Securing a Loose Cannon 46 Classifieds www.sfvba.org MARCH 2020 ■ Valley Lawyer 5 Jack G. Cohen COURT QUALIFIED AUTOMOBILE EXPERT WITNESS, LICENSED SAN FERNANDO VALLEY BAR ASSOCIATION AUTOMOBILE DEALER 20750 Ventura Boulevard, Suite 140 Woodland Hills, CA 91364 30 years experience in the automotive industry Phone (818) 227-0490 Fax (818) 227-0499 Plaintiff and Defense www.sfvba.org Consulting with attorneys, dealers, EDITOR Michael D. White consumers, insurance companies GRAPHIC DESIGNER Marina Senderov OFFICE: 747.222.1550 « CELL: 747.222.1554 EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICERS 2629 Townsgate Road, Suite 110 « Westlake Village, CA 91361 President ..................................Barry P. Goldberg President-Elect .........................David G. -

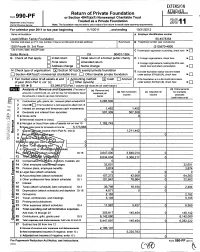

Form 990-PF Or Section 4947(A)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated As a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2011 Note

EXTENSION Return of, Private Foundation OMAGI 052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2011 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2011 or tax year beginning 11/1/2011 , and ending 10/31/2012 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Lowell Milken Family Foundation 95-4078354 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1250 Fourth St. 3rd Floor (310) 570-4800 City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► Santa Monica CA 90401-1304 q q q G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q q Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change q Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check of organization: Section exempt private foundation type 501 (c)(3) E If private foundation status was terminated q q q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method: Cash q Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q of year (from Part 11, col (c), q Other (specify) ------------------------- under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► line 16) ► $ 63 046,972 Part 1, column (d) must be on -

“Deck the Walls” Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf®

The Help Group ... because every child deserves a great future FALL 2009 BRIAN GOLDNER, MARY URQUHART & MAX MAYER TO BE HONORED AT THE HELP GROUP’S 2009 TEDDY BEAR BALL he Help Group is pleased to announce that has helped to create brighter futures for children three remarkable individuals will be honored with autism. Max Mayer, the gifted writer-director of T at The Help Group’s 2009 Teddy Bear Ball. the acclaimed motion picture “Adam,” will receive This 13th annual holiday the Spirit of Hope Award gala celebration will be for raising important held on Monday, December public awareness and 7th, 2009, at the Beverly understanding through Hilton Hotel. his sensitive portrayal of a young man with Asperger’s BRIAN GOLDNER Brian Goldner, President Disorder. Gala Chairs are and CEO of Hasbro Inc., Brian Grazer, Cheryl & will receive The Help Haim Saban, and Bill Group’s Help Humanitarian Urquhart. MARY URQUHART MAX MAYER Award in recognition of his far-reaching philanthropic leadership and A toy industry veteran, Brian Goldner is widely commitment to children’s causes. Parent advocate recognized for leading the evolution of Hasbro from Mary Urquhart will receive the Champion for Children Award in a traditional toy and game company to a leader in world-class recognition of her heartfelt spirit of giving and volunteerism that family entertainment. Brian is responsible for Hasbro’s business continued on page 3 THE HELP GROUP’S NEW AUTISM CENTER CURRENTLY UNDER CONSTRUCTION “Deck the Walls” DEDICATED TO EDUCATION, RESEARCH, PARENT & PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND OUTREACH for The Help Group children at your local Coffee Bean & Tea Lea f® this holiday season! see story on page 5 see story on page 7 BOARD OF DIRECTORS CIRCLE OF FRIENDS Gary H. -

Lowell Milken: Teacher Leaders As the Opportunity

TEACHER LEADERS AS THE OPPORTUNITY by Lowell Milken TEACHER LEADERS AS THE OPPORTUNITY TEACHER LEADERS AS THE OPPORTUNITY INTRODUCTION I believe one of the most important things we can do in this life is make the most of the opportunities it affords. Those opportunities are vast and varied. Some are hidden. Others are evident. For highly effective teachers, the opportunities are in plain sight. And none is more important than leading other teachers to maximum effectiveness. This is the focus of this presentation. Leadership in teachers. How to create and how to expand it. The effective teacher in the classroom is both the starting point and the engine of excellent and meaningful education. That’s because excellent teachers are not only the single most important in-school factor in student learning,1 the best of them are the key factor in improving the instructional practices and strengthening the skills of their peers.2 It is completely relevant to this topic that 2018 marks the 20th year of the TAP System for Teacher and Student Advancement (TAP), a system I believed was possible and knew was necessary.3 A system I set about creating because the quality of an education system depends— absolutely—upon the quality of its educators. It is also relevant that the representation among educators and education officials is exceptionally broad at this conference: state policymakers and officials, college leaders, district officials, principals, master, mentor and career teachers, foundation and community leaders, and Milken Educator Award recipients. I mention this breadth because it’s going to take this range of professionals and participants to truly fulfill the promise of TAP, of which teacher leadership is an integral part. -

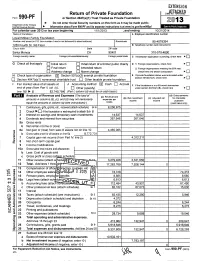

Z 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION Return of Private Foundation CIM13NT c P Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation P. Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990 For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginni 11/1/2013 , and 10/31/2014 Name of foundation A Employer identification number nwPll Milken Famdv Fnunriattnn Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite 95-4078354 1250 Fourth St 3rd Floor B Telephone number (see instructions) City or town State ZIP code Santa Monica CA 90401 310-570-4800 q Foreign country name Foreign province/state/county Foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ► q q G Check all that apply Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change q Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization Q Section 501(c)(3 ) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A) , check here q q Section 4947 ( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation ► q q I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part fl, col (c), q Other ( specify) under -

Early Childhood

2016–17 ANNUAL REPORT Our Vision The vision of Wise School is to inspire and empower our students and their families to learn deeply about our world and Jewish heritage, to be creative, and to experience wholeness so that we can make great happen in our community, our nation, Israel, and the world. Our Mission At Wise School, through depth, complexity and differentiation, our students learn how to learn. Children build knowledge as they ask questions, research, solve problems, and add layers to their understanding. Through the application of creativity, children voice their independence, expand their minds, and work towards achieving their greatest potential. Students become creators instead of consumers; they focus more on the process than the product. Students maximize their opportunity to stand out in a competitive world by looking at life through innovative lenses. shleimut), by making interdisciplinary – שלימות) Our students experience wholeness connections through development of mind, body, and soul. We acknowledge and appreciate moments of Shalom. We recognize each student’s strengths and contributions as we build an inclusive community. We honor our Jewish faith as a living heritage, begin to develop a deep understanding of and commitment to Israel, and develop proficiency in and appreciation of the Hebrew language. At Wise School, thoughtful people inspire meaningful actions in order to make great .(repair of the world – תיקון עולם) happen through acts of Tikkun Olam STAFF LEADERSHIP 2016–2017 Rabbi Yoshi Zweiback Malka Clement -

Wednesday December 9, 2015 at the Beverly Hilton

1 HelpLine The Help Group...because every child deserves a great future 2015 SPECIAL HOLIDAY EDITION MIKE HOPKINS AND TOM KOMP TO BE HONORED AT THE HELP GROUP'S TEDDY BEAR BALL Wednesday December 9, 2015 at The Beverly Hilton The Help Group is pleased of Distribution for Fox Networks, he oversaw Fox Networks to announce that Mike broadcast distribution agreements, and the strategy, sales Hopkins, Chief Executive and marketing for Fox’s 45 linear and non-linear U.S. cable Officer of Hulu, will be networks. Under his leadership, his team also developed recognized with its 2015 many of the television industry’s leading authenticated and Help Humanitarian Award digital video products, including BTN2Go, FXNOW, FOX at the 18th Annual Teddy Bear Ball on December 9 at the Sports Go, and FOX NOW. Mike served as a member of the Beverly Hilton Hotel. That same night, Tom Komp, Senior Hulu board for over two years prior to being named CEO, and Vice President of The Help Group, will be recognized with holds a number of leadership roles in industry organizations. the Champion for Children Award. The Help Group is proud to recognize its 2015 Champion for This year’s Gala Chairs are Rich Battista, Executive VP of Time Children Award recipient, Tom Komp. Tom’s long-standing Mike Hopkins Inc.; John Landgraf, President and General Manager of FX and remarkable efforts have touched the Network; Steve Mosko, Chairman of Sony Pictures Television; lives of countless children with special Eric Shanks, President, COO and Executive Producer of FOX Sports; and Ben needs and their families. -

Milken Institute Global Conference from Theappstore Orgoogleplay

MISSION STATEMENT Our mission is to increase global prosperity by advancing collaborative solutions that widen access to capital, create jobs and improve health. We do this through independent, data-driven research, action-oriented meetings, and meaningful policy initiatives. 1250 Fourth Street 1101 New York Avenue NW, Suite 620 137 Market Street #10-02 Santa Monica, CA 90401 Washington, DC 20005 Singapore 048943 Phone: 310-570-4600 Phone: 202-336-8900 Phone: 65-9457-0212 #MIGLOBAL AGENDA | LOS ANGELES | APRIL 28 - MAY 1 E-mail: [email protected] • www.milkeninstitute.org download the Global Conference mobileapp download theGlobalConference descriptions and up-to-date programming information, information, descriptions andup-to-dateprogramming AT YOUR FINGER TIPS YOUR AT To find complete speaker biographies, panel findcompletespeakerbiographies, panel To SEE: requests andconnectwithparticipants requests CONNECT: speaker biographies,andvenuemaps Milken Institute Global Conference Global Institute Milken from the App Store orGooglePlay. theAppStore from CUSTOMIZE: the full agenda, panel descriptions, the fullagenda,paneldescriptions, and personalschedule opt-in to make meeting opt-in tomakemeeting your profile your profile MIGlobal WILSHIRE BOULEVARD WILSHIRE ENTRANCE 11 12 13 14 15 16 SALES & CATERING WELLNESS GARDEN CORPORATE EVENTS 21 CA WILSHIRE GARDEN TERRACE LOBBY EXECUTIVE GIFT SHOP BAR 17 18 19 20 OFFICES 4 Networking Areas 8 PAVILION LOUNGE VALET 22 7 5 Pavilion Lounge 9 6 Lobby Bar 10 Wilshire Garden Circa 55 (Lower Level) -

Greetings and Introductions Welcome Remarks

Lowell Milken Family Foundation HighTechHigh-LA A California Charter School Dedication Ceremonies Wednesday, November 17, 2004 Program Greetings and Introductions Roberta Weintraub As an educational entrepreneur, Roberta Weintraub is Founder/Executive Director, the spark that ignites HighTechHigh-LA. She has been HighTechHigh-LA Foundation instrumental in securing federal, state and local funds, architectural expertise and industry partnerships. She was a member of the Los Angeles Board of Education for 14 years (board president for three years). She founded the highly successful Police Academy Magnet program, now on six LAUSD school sites. Ms. Weintraub has had a distinguished media career in both radio and television, and has received two Emmys for educational programming. She has a B.A. degree from U.C.L.A. Welcome Marsha Rybin Marsha Rybin earned a B.A. and M.S. in history from U.C.L.A. Founding Principal, and an M.S. in educational administration from National HighTechHigh-LA University. She has taught at Muir Junior High School, Porter Junior High School and Birmingham High School, where she was the journalism/technology coordinator and later assistant principal. Her professional affiliations include the California Council on Social Studies, California Charter School Association, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Associated Administrators of Los Angeles, and the National Association of Secondary School Principals. Remarks Jack O’Connell Superintendent Jack O’Connell has worked to fortify California State Superintendent California’s academic standards, strengthen California’s of Public Instruction assessment system, and bolster support for the state’s classrooms. He is a long-time advocate for smaller class sizes, improved teacher recruitment and retention, comprehensive testing, and up-to-date school facilities. -

Download Magazine

TRANSFORM EMPOWER ADVANCE EMPOWER AD- VANCE TRANSFORM ADVANCE FALL EMPOWER TRANS- 2016 UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW VOL. OFFICE OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS FORM EMPOWER TRANSFORM ADVANCE 405 HILGARD AVENUE 39 BOX 951476 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90095-1476 ADVANCE TRANSFORM EMPOWER AD EM- POWER ADVANCE TRANSFORM MANCE TRANSFORM EMPOWERTHE WILLIAMS INSTITUTE 15 AT INNOVATION A ADVANCE TR EMEM- POWER ADVANCE ANSFORM EMPOWER ADVANCE ERwhat ADVANCE difference can you make in your EMPOWER lifetime? RESEARCH EER TRANSFORM AD- VANCElaw.ucla.edu/centennialcampaign TRANSFORM EMPOWERREAL-WORLD ADVANCE TRANS- FORM ADVANCE EMPOWER TRANSFORM EMPOW- ER TRANSFORM ADVANCEIMPACT EMPOWER ADVANCE TRANSFORM EMPOWER THETRANSFORM WILLIAMS INSTITUTE EMPOWER AT 15 EMPOWER TRANSFORM ADVANCE TRANSFORM EMPOWER ADVANCE TRANSFORM ADVANCE EM- POWER TRANSFORM EMPOWER TRANSFORM AD- Message from Dean Jennifer L. Mnookin Intellectual engagement and real-world impact Stay also are in plentiful supply in our Supreme Court Clinic. Astonishingly, the clinic wrote briefs on the merits in four U.S. Supreme Court cases in the 2015-16 term, giving students a view of the High Court that few Connected practitioners ever see. In fact, examples abound, both in these pages with ! and around the law school, of impact and intellectual engagement. This year, a group of UCLA Law students VISIT US: helped persuade President Obama to grant clemency to a prisoner serving a life sentence for a nonviolent drug K law.ucla.edu crime. Another student helped launch a medical device company that can dramatically reduce discomfort and LIKE US: costs for elderly patients. His team won $100,000 in K the inaugural Lowell Milken Institute-Sandler Prize facebook.com/UCLA-School-of-Law-Official for New Entrepreneurs, a contest designed to spur entrepreneurship across the university. -

Breadth of Influence $10 Million Gift Transforms Business Law and Policy Teaching and Research

FALL 2011 VOL. 34 NO. 1 201134FALL VOL. NO. 405 Hilgard Avenue Box 951476 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1476 Breadth of Influence $10 million gift transforms business law and policy teaching and research ImpactIng the natIon A profile of Senator Kirsten Gillibrand ’91 Q&w a Ith ValerIe B. Jarrett Senior Advisor to President Obama 214522_Cover_R3.indd 1 9/8/2011 9:36:25 AM contents FALL 2011 VOL. 34 NO. 1 © 2011 REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW OFFICE OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS BOX 951476 | LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90095-1476 74 r achel f. moran UCL a Law BOaRD Of aDvISORS 52 dean and Michael J. connell Kenneth Ziffren ’65, chair distinguished Professor of law nancy l. abell ’79 James d. c. Barrall ’75 Sam martinuzzi Jonathan f. chait ’75 associate dean, external affairs Stephen claman ’59 lauri l. gavel Melanie K. cook ’78 executive director of david J. epstein ’64 communications david W. fleming ’59 70 richard I. Gilchrist ’71 EDITORS arthur n. Greenberg ’52 Bernard a. Greenberg ’58 impacting the nation q&a with l auri l. gavel international justice antonia hernández ’74 executive director of valerie b. jarrett clinic travels abroad Margarita Paláu hernández ’85 a profile of Senator communications Joseph K. Kornwasser ’72 Kirsten Gillibrand ’91. Senior advisor to International Justice clinic Sara rouche Stewart c. Kwoh ’74 President obama students travel abroad to communications officer Victor B. Macfarlane ’78 discusses her career. Michael t. Masin ’69 explore witness protection DESIGN Wendy Munger ’77 challenges. r ebekah albrecht Greg M. nitzkowski ’84 contributing Graphic designer nelson c. -

Educator Awards Luncheon

29th Annual Jewish Educator Awards Luncheon Luxe Sunset Boulevard Hotel Los Angeles December 13, 2018 29th Annual Jewish Educator Awards Luncheon Luxe Sunset Boulevard Hotel Los Angeles December 13, 2018 Sponsored by the Milken Family Foundation in cooperation with BJE, a beneficiary agency of The Jewish Federation Message from the MILKEN FAMILY FOUNDATION How do we, as a community and as a people, best educate the next generation to lead and ensure a meaningful Jewish future? This question has been discussed with Talmudic intensity by Jews over the ages. Research conducted in recent decades reveals that the earlier a child begins Jewish education, the more likely he or she is to remain connected later in life. Early childhood education in a Jewish setting has the added benefit of nurturing a Jewish influence on the family as a whole. As a child matures, every additional year of a Jewish day school education—particularly past the bar or bat mitzvah year—further solidifies a strong Jewish connection and understanding of that tradition and responsibility for living life according to these values. According to recent studies, 40 percent of today’s young Jewish leaders attended Jewish day schools. Combined, these factors point to a shared conclusion: Jewish day schools are important and worth the investment of effort, time and resources for all of us who care about ensuring a meaningful Jewish future. This places a great sense of duty upon those who deliver that education to maintain high standards of rigor, inspiration and results, whether Orthodox, Conservative, Reform or Community schools. If we are truly committed to the goals inherent in combining a secular education with the traditions and tenets of our faith, then it is up to all of us to ensure that high-quality professional learning is the norm, that resources are sufficient, and that teachers have opportunities to develop and flourish.