Language in Utopian Societies: a Study of Works by Le Guin, Atwood, and Lowry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atheist's Bible: Diderot's 'Éléments De Physiologie'

The Atheist’s Bible Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie Caroline Warman In off ering the fi rst book-length study of the ‘Éléments de physiologie’, Warman raises the stakes high: she wants to show that, far from being a long-unknown draf , it is a powerful philosophical work whose hidden presence was visible in certain circles from the Revolut on on. And it works! Warman’s study is original and st mulat ng, a historical invest gat on that is both rigorous and fascinat ng. —François Pépin, École normale supérieure, Lyon This is high-quality intellectual and literary history, the erudit on and close argument suff used by a wit and humour Diderot himself would surely have appreciated. —Michael Moriarty, University of Cambridge In ‘The Atheist’s Bible’, Caroline Warman applies def , tenacious and of en wit y textual detect ve work to the case, as she explores the shadowy passage and infl uence of Diderot’s materialist writ ngs in manuscript samizdat-like form from the Revolut onary era through to the Restorat on. —Colin Jones, Queen Mary University of London ‘Love is harder to explain than hunger, for a piece of fruit does not feel the desire to be eaten’: Denis Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie presents a world in fl ux, turning on the rela� onship between man, ma� er and mind. In this late work, Diderot delves playfully into the rela� onship between bodily sensa� on, emo� on and percep� on, and asks his readers what it means to be human in the absence of a soul. -

The OT Is the World's Supreme Document on the Subject of Justice. God Purposes, After and Through the Cosmic-Historic Mess [&Quo

LIBERTY AND/OR EQUALITY in relation to the four isms Elliott #856 The OT is the world's supreme document on the subject of justice. God purposes, after and through the cosmic-historic mess ["the the victory of "righteous- ness and justice" [Gen.18.19] through a nation [Gen.12.2] different from the other nations [Num.23.9]--a nation founded on faith [Abraham in Gen.] and obedience [Moses in Ex.--the two sagas converged in the Joseph-reconciliation saga]. When the nation self-idolatrizes into nationalism, God's purpose of "righteousness [in character] and justice [in structure and processl"is frustrant. When faith/liberty vaunt them- selves over obedience/equality, justice is destroyed [a tendency of Declaration of Independence thinking]. When the reverse occurs, again justice is destroyed [as in the Communist Manifesto, which reverts romantically to the pre-nation communitar- ian ideal--a despotic regime setting itself up, in anticipation of the withering away of the state, on behalf of the proles as "the dictatorship of the proletariatl. 1. Neither of the two nation motifs now dominating the globe bodies forth the bib- lical ideal of "liberty with justice [in equality] for all." "Democracy" [the liber- ty motif] and "communism" [the equality motif] are alike in dedication to justice. NB: As ideal terms, I follow here my old teacher Mortimer Adler: "democracy" as the ideal term for political justice, "socialism" as the ideal term for economic justice --and "communism" useless as an ideal term, for it combines "socialism" and tyranny, buying pseudo-equaity at the price of liberty [i.e., political justice, "freedom," the rights of the individual as spelled out in the UN's "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" 7rwhich is thinksheet #831]. -

Gathering Blue, and the Ways in Which Different Characters Have Power Over Each Other

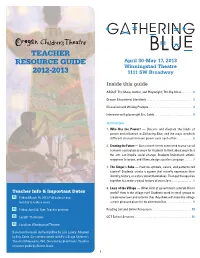

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE April 30-May 17, 2013 Winningstad Theatre 2012-2013 1111 SW Broadway Inside this guide ABOUT: The Show, Author, and Playwright; The Big Ideas ........2 Oregon Educational Standards .................................3 Discussion and Writing Prompts................................4 Interview with playwright Eric Coble............................5 Activities 1. Who Has the Power? — Discuss and diagram the kinds of power and influence in Gathering Blue, and the ways in which different characters have power over each other. ..........6 2. Creating the Future — Use current events connected to your social sciences curriculum as ways for students to think about ways that the arts can inspire social change. Students brainstorm artistic responses to issues, and if time, design a poster campaign. ......7 3. The Singer’s Robe — How do symbols, colors, and patterns tell stories? Students create a square that visually expresses their identity, history, or a story about themselves. Then put the squares together to create a visual history of your class................8 4. Laws of the Village — What kind of government controls Kira’s Teacher Info & Important Dates world? How is the village run? Students work in small groups to Friday, March 15, 2013: Full balance due, create new laws and reforms that they think will make the village last day to reduce seats a more pleasant place for its citizens to live. ..................9 Friday, April 26, 7pm: Teacher preview Reading List and Online Resources ............................10 Length: 75 minutes OCT School Services .........................................12 Location: Winningstad Theatre Based on the book Gathering Blue by Lois Lowry. Adapted by Eric Coble. Co-commissioned with First Stage Children’s Theatre (Milwaukee, WI). -

9780748678662.Pdf

PREHISTORIC MYTHS IN MODERN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd i 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iiii 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM PREHISTORIC MYTHS IN MODERN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iiiiii 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall, 2017 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 7866 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 7867 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7869 3 (epub) The right of Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall to be identifi ed as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55200_Widerquist.indd200_Widerquist.indd iivv 225/11/165/11/16 110:320:32 AAMM CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgments -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Looking Back a Book of Memories by Lois Lowry

Looking Back A Book Of Memories by Lois Lowry Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited books*. Accessible on all your screens. Ebook Looking Back A Book Of Memories available for review only, if you need complete ebook "Looking Back A Book Of Memories" please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >>> *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every book is in the library. You can choose FREE Trial service and download "Looking Back A Book Of Memories" ebook for free. Book File Details: Review: Lois Lowry is my favorite author of all time. The Giver has always been an important book to me. So when I found out about this book I was ecstatic to read it. I read it in one sitting. It is much different than what you would usually expect from a memoir or biography. There is no order to the events in this book. It honestly feels like I just sat in... Original title: Looking Back: A Book Of Memories Age Range: 12 and up Grade Level: 7 - 9 Paperback: 272 pages Publisher: Young Readers Paperback; Revised, Expanded edition (August 1, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 054493248X ISBN-13: 978-0544932487 Product Dimensions:6 x 0.7 x 9 inches File Format: pdf File Size: 4806 kB Ebook File Tags: lois lowry pdf,looking back pdf,book of memories pdf,anastasia krupnik pdf,back a book pdf,makes me want pdf,autumn street pdf,black and white pdf,must read pdf,want to learn pdf,updated version pdf,world war pdf,young readers pdf,want to weep pdf,chapter begins pdf,highly recommend pdf,characters in her books pdf,read this book pdf,worth reading pdf,photo album Description: (star) A compelling and inspirational portrait of the author emerges from these vivid snapshots of lifes joyful, sad and surprising moments.--Publishers Weekly, starred reviewIn this moving autobiography, Lois Lowry explores her rich history through personal photographs, memories, and recollections of childhood friends. -

The Machinery of Freedom Guide to a Radical Capitalism 3Rd Edition Download Free

THE MACHINERY OF FREEDOM GUIDE TO A RADICAL CAPITALISM 3RD EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Friedman | 9781507785607 | | | | | The machinery of freedom Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Liberty magazine named the book among The Top Ten Best Libertarian Bookspraising Friedman for tackling the problems related to private national defense systems and attempting to solve them. In The Black Swan Taleb outlined a problem, and in Antifragile he offers a definitive solution: how to gain from disorder and chaos while being protected from fragilities and adverse events. Bruce L. The final section introduces a number of new topics, including unschooling, the misuse of externality arguments in contexts such as population or global warming, and the implications of public key encryption and related online technologies. Most Helpful Most Recent. The recording itself is one of the worst I've ever listened to. By: David D. In my top 3 favorite books This book taught me to find spontaneous order in more places than I ever thought possible. The machinery of freedom A non fiction book by David D Friedman. The author narrates it The Machinery of Freedom Guide to a Radical Capitalism 3rd edition, which is great if you're used to his speaking. If you are interested in freedom and how it could work without a government this is the book for you! In my top 3 favorite books This book taught me to find spontaneous order in more places than I ever thought possible. In For a New Liberty: The Libertarian ManifestoRothbard proposes a once-and- for-all escape from the two major political parties, the ideologies they embrace, and their central plans for using state power against people. -

A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History

LeftLiberty “It is the clash of ideas that casts the light!” The Gift Economy OF PROPERTY. __________ A Journal of Mutualist Anarchist Theory and History. NUMBER 2 August 2009 LeftLiberty It is the clash of ideas that casts the light! __________ “The Gift Economy of Property.” Issue Two.—August, 2009. __________ Contents: Alligations—A Tale of Three Approximations 2 New Proudhon Library Announcing Justice in the Revolution and in the Church—Part I 6 The Theory of Property, Chapter IX—Conclusion 8 Collective Reason “A Little Theory,” by Errico Malatesta 23 “The Mini-Manual of the Individualist Anarchist,” by Emile Armand 29 From the Libertarian Labyrinth 34 Socialism in the Plant World 35 “Mormon Co-operation,” by Dyer D. Lum 38 “Thomas Paine’s Anarchism,” by William Van Der Weyde 41 Mutualism: The Anarchism of Approximations Mutualism is APPROXIMATE 45 Mutualist Musings on Property 50 The Distributive Passions Another World is Possible, “At the Apex,” I 72 On alliance “Everyone here disagrees” 85 Editor: Shawn P. Wilbur A CORVUS EDITION LeftLiberty: the Gift Economy of Property: If several persons want to see the whole of a landscape, there is only one way, and that is, to turn their back to one another. If soldiers are sent out as scouts, and all turn the same way, observing only one point of the horizon, they will most likely return without having discovered anything. Truth is like light. It does not come to us from one point; it is reflected by all objects at the same time; it strikes us from every direction, and in a thousand ways. -

Democracy - the God That Failed: the Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy and Natural Order Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DEMOCRACY - THE GOD THAT FAILED: THE ECONOMICS AND POLITICS OF MONARCHY, DEMOCRACY AND NATURAL ORDER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hans-Hermann Hoppe | 220 pages | 31 Oct 2001 | Transaction Publishers | 9780765808684 | English | Somerset, NJ, United States Democracy - The God That Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy and Natural Order PDF Book Having established a natural order as superior on utilitarian grounds, the author goes on to assess the prospects for achieving a natural order. He defends the proper role of the production of defense as undertaken by insurance companies on a free market, and describes the emergence of private law among competing insurers. Original Title. Revisionist in nature, it reaches the conclusion that monarchy is a lesser evil than democracy, but outlines deficiencies in both. Meanwhile, both monarchy and democracy are both parasitic; differing only in that monarchy being a private parasitism is generally less destructive. Average rating 4. This is my "staple of libertarian" must-reads. Feb 15, Trey Smith rated it it was amazing. Rating details. Accept all Manage Cookies Cookie Preferences We use cookies and similar tools, including those used by approved third parties collectively, "cookies" for the purposes described below. Revisionist in nature, it reaches the conclusion that monarchy is a lesser evil than democracy, but outlines deficiencies in both. An austro-libertarian reconstruction of man's development. If such a caste is to mobilize, this scholarly work must be treated as a foundation for the transition. Book ratings by Goodreads. Steve Richards. Nov 12, Adrian Dorney rated it it was amazing. So I'll give a bit of pros and cons. -

The Giver Quartet: Gathering Blue Freedom As They Had Previously Thought

FREE THE GIVER QUARTET: GATHERING BLUE PDF Lois Lowry | 256 pages | 31 Jul 2014 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007597260 | English | London, United Kingdom The Giver Quartet - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Gathering Blue by Lois Lowry. In her strongest work to date, Lois Lowry once again creates a mysterious but plausible future world. It is a society ruled by savagery and deceit that shuns and discards the weak. Left orphaned and physically flawed, young Kira faces a frightening, uncertain future. Blessed with an almost magical talent that keeps her alive, she struggles with ever broadening responsibili In her strongest work to date, Lois Lowry once again creates a mysterious but plausible future world. Blessed with an almost magical talent that keeps her alive, she struggles with ever broadening responsibilities in her quest for truth, discovering things that will change her life forever. As she did in The GiverLowry challenges readers to imagine what our world could become, and what will be considered valuable. Every reader will be taken by Kira's plight and will long ponder her haunting world and the hope for the future. Get A Copy. PaperbackReader's Circlepages. Published September 25th by Delacorte Press first published September More Details Original Title. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

Literature Circle Guide – Number the Stars

Literature Circle Guide: Number the Stars by Tara McCarthy SCHOLASTIC PROFESSIONAL B OOKS New York • Toronto • London • Auckland • Sydney • Mexico City • New Delhi • Hong Kong • Buenos Aires Literature Circle Guide: Number the Stars © Scholastic Teaching Resources Scholastic Inc. grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducibles from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Professional Books, 555 Broadway, New York, NY 10012-3999. Guide written by Tara McCarthy Edited by Sarah Glasscock Cover design by Niloufar Safavieh Interior design by Grafica, Inc. Interior illustrations by Mona Mark Credits Cover: Jacket cover for NUMBER THE STARS by Lois Lowry. Copyright © 1962 by Lois Lowry. Used by permission of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Scholastic Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-439-27170-3 Printed in the U.S.A. Literature Circle Guide: Number the Stars © Scholastic Teaching Resources Contents To the Teacher . 4 Using the Literature Circle Guides in Your Classroom . 5 Setting Up Literature Response Journals . 7 The Good Discussion . 8 About Number the Stars . 9 About the Author: Lois Lowry . 9 Enrichment Readings: World War II and the Holocaust, Underground Movements, Historical Fiction . .10 Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Before Reading the Book . .13 Group Discussion Reproducible: Before Reading the Book . .14 Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 1-2 . -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.