Staging the Past: Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle in Divided Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

(W) 1974 P 2 Geschichte Aus Der Produktion 2

ABKÜRZUNGSVERZEICHNIS Sammelausgaben P 1 Geschichten aus der Produktion 1. Stücke Prosa, Gedichte, Proto kolle, Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1974 P 2 Geschichte aus der Produktion 2. Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1974 U Die Umsiedlerin oder das Leben auf dem Lande, Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1975 TA Theater-Arbeit, Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1975 G Germania Tod in Berlin, Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1977 M Mauser, Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin (W) 1978 St Stücke, mit einem Nachwort von Rolf Rohmer, Henschel-Verlag, Berlin (0) 1975 STG Die Schlacht, Traktor, Leben Gundlings Friedrich von Preußen Lessings Schlaf Traum Schrei, mit einem Nachwort von Joachim Fiebach, Henschel-Verlag, Berlin (0) 1977 Zeitschriften TH Theater Heute TdZ Theater der Zeit NDL Neue Deutsche Literatur SuF Sinn und Form WB Weimarer Beiträge FR Frankfurter Rundschau Werk bibliographie (bislang ausführlichste); in: »Hamletmaschine. Heiner Müllers Endspiel« hg. von Theo Girshausen, Köln 1978, S. 172-175. 183 BIBLIOGRAPHIE Dramen Das Laken (1951) in: SuF Sonderheft 1, 1966, S. 767-768 (unter dem Titel »Das Laken oder die unbefleckte Empfängnis« und mit einem erweiter ten Schlußdialog die Schlußszene von »Die Schlacht«) VA 1974 in der Volksbühne Berlin (»Spektakel 2) Die Reise (nach Motekiyo) (1951) in: G. S. 17-19. Nach Kagekijo, der Böse von Seami, in: Elisabeth Hauptmann, »Julia ohne Romeo«, Geschichten, Stücke, Aufsätze, Erinnerungen, hg. von R. Eggert und R. Hili, Berlin Weimar 1977, S. 159ff. Der Lohndrücker (Mitarbeit: Inge Müller) (1956) in: NDL, H. 5 (1957) S. 116-141 Henschel Verlag Berlin 1958 (ohne Vorspann) VEB Friedrich Hofmeister Verlag, Leipzig 1959 Kursbuch H. 7, S. 23-51, Ffm. -

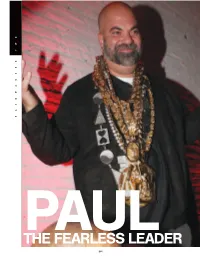

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Alberichs Fluch

„Meiner Freiheit erster Gruß“ Alberichs Fluch (von Gunter Grimm; Dezember 2019) Alberich und die Rheintöchter Alberich ist der Herr der versklavten Zwerge, ein dämonischer Bursche, der darüber hinaus die Zau- berkunst beherrscht. Er besitzt einen Tarnhelm, der ihn unsichtbar macht, und einen magischen Ring, mit dessen Hilfe er Gold hortet und durch Erwerb und Bestechung die Weltherrschaft erringen möchte. Er ist also ein Kapitalist übler Sorte! Es versteht sich, dass Wotan sich dieses verheerende Treiben nicht gefallen lassen darf – schließlich dünkt er sich ja als Göttervater und Herr der Welt. Deshalb wogt in den vier Teilen der „Ring“-Tetralogie unentwegt der Kampf um den Ring. Im Grunde sind all die menschlichen Protagonisten der zwei Generationen: Siegmund und Sieglinde, hernach Siegfried, Gutrune und die Burgunder, nur Instrumente im Kampf um den Besitz des Ringes. Anders sieht das bei den übergeordneten Instanzen aus Götter- und Dämonenwelt: Wotan und Brünnhilde, Alberich und Hagen sind Gegenmächte – freilich nicht eindeutig als die gute und die böse Partei identifizierbar. Im ersten Teil der Tetralogie, im „Rheingold“ wird die Grundkonstellation angelegt. Die Rheintöchter besitzen das mythische Rheingold, dessen Besitz zu uneingeschränkter Macht verhilft, wenn sein Be- sitzer aus diesem Gold einen Ring schmiedet und zugleich der Liebe abschwört. Die Ausgangssituati- on ist der vergebliche Versuch des Zwergenkönigs Alberich, eine der Rheintöchter für sich zu erobern. Sie erzählen ihm vom Gold und dass derjenige, welcher der Liebe entsage, aus dem Gold einen Ring schmieden könne, der ihm quasi die Weltherrschaft verleihen würde. Das leuchtet dem Zwerg derma- ßen ein, dass er den Bericht umgehend in die Tat umsetzt. -

Floor Plans for First and Third Floors of the Newly-Leased Building

VOLUME 78, ISSUE 6 For the Students and the Community November 13, 2000 Honors College Prvsident Speaks at Leadership Weekend Gets Approval By Adam Ostaszewski "The department has not had 3. great News Editor history at Baruch- in fact it's had a bad one." said Regan. "Mv goal is to Baruch and Beyond ~ - ~ Addressing a crowd of more than strengthen it." Regan even alluded to By Edward Ellis roo student leaders at the 17th annu the department's initiative to add a Contributing Writer al Leadership Weekend. Baruch Caribbean Studies department. President Edward Regan responded The president also addressed sever The City University of New York to the recent controversy surrounding al other issues on a wide variety of has begun recruiting 100 students to the resignation ofBlack and Hispanic topics. ranging from the new building participate in the first-ever Honors Studies Department Chair Arthur to fundraising to his vision for set College. The $5 million project is _._---Lewin.~ Baruch. to begin in the fall 200I. The pro Regan failed to address the resigna- Regan expects that Baruch wi II gram will target students with at tion of Lewin, but mentioned the continue to improve in every way. He .least a 1350 SAT score in addition to recent resignation on another profes noted that the SAT scores of incom other criteria: sor of the same department. "She ing freshmen. as well as starting Members of the Honors College resigned against my urging," said salaries for Baruch graduates are on will study at Baruch. Brooklyn. City, Regan, referring to Professor Martha the rise. -

Transatlantic Crossings in J989

SNEAK PREVIEW'S AND TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS IN J989 BY ELLEN LAMPERT he Welsh National Opera rang in the Richard Peduzzi, whose design collaboration New York with its American debut at with Patrice Chereau stretches over the past twenty the Brooklyn Academy of Music in years, is already at work on the decor for Cher • February with Peter Stein's production eau 's production of Mozart's Don Giovanni, Designer Reinhard Heinrich, Tof Falstaff. With sets designed by Lucio Fanti, who scheduled to open the new French Opera House at who recently made his direc also designed Stein's WNO production of Othello, the Bastille in January 1990. The building, cur torial debut with the Nether and costumes by Moidele Bickel, the production rently under construction, will host a concert on lands Opera production of was filmed in Cardiff by the BBC for an airdate la July 14, as a sentimental offering to this year's bi The Damnation ofFaust, will centennial celebration of the French Revolution, direct and design Lulu ter in 1989. (model, I) for the Heidelburg New productions on the Welsh National Opera's but full-staged productions are not scheduled until Theatre. Opening is set for 1989 home schedule include Mozart's Seraglio, di 1990. May89. rected by Giles Havergal, with sets and costumes by Back in Germany, Reinhold Daberto, from Russell Craig, who also designed the WNO/Mozart Acoustic Biihnentechnik, is overseeing extens ive The Marriage of Figaro. This production debuts renovations of the stage machinery at the Munich • on March 11 , to be followed in May with La Son Opera. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVIII, Number 1 April 2003 A PILGRIMAGE TO IOWA As I sat in the United Airways terminal of O’Hare International Airport, waiting for the recently bankrupt carrier to locate and then install an electric starter for the no. 2 engine, my mind kept returning to David Lodge’s description of the modern academic conference. In Small World (required airport reading for any twenty-first century academic), Lodge writes: “The modern conference resembles the pilgrimage of medieval Christendom in that it allows the participants to indulge themselves in all the pleasures and diversions of travel while appearing to be austerely bent on self-improvement.” He continues by listing the “penitential exercises” which normally accompany the enterprise, though, oddly enough, he omits airport delays. To be sure, the companionship in the terminal (which included nearly a dozen conferees) was anything but penitential, still, I could not help wondering if the delay was prophecy or merely a glitch. The Maryland Handel Festival was a tough act to follow and I, and perhaps others, were apprehensive about whether Handel in Iowa would live up to the high standards set by its august predecessor. In one way the comparison is inappropriate. By the time I started attending the Maryland conference (in the early ‘90’s), it was a first-rate operation, a Cadillac among festivals. Comparing a one-year event with a two-decade institution is unfair, though I am sure in the minds of many it was inevitable. Fortunately, I feel that the experience in Iowa compared very favorably with what many of us had grown accustomed Frontispiece from William Coxe, Anecdotes fo George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith to in Maryland. -

18 December 2020 Page 1 of 22

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 December 2020 Page 1 of 22 SATURDAY 12 DECEMBER 2020 Wolfgang Kube (oboe), Andrew Joy (horn), Rainer Jurkiewicz (horn), Rhoda Patrick (bassoon), Bernhard Forck (director) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000q3cy) Renaud Capuçon and Andras Schiff 04:46 AM Clara Schumann (1819-1896) Violin sonatas by Debussy, Schumann and Franck recorded at 4 Pieces fugitives for piano, Op 15 the Verbier Festival. Catriona Young presents. Angela Cheng (piano) 01:01 AM 05:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Jozef Elsner (1769-1854) Violin Sonata in G minor, L 140 Echo w leise (Overture) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Andrzej Straszynski (conductor) 01:14 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) 05:07 AM Violin Sonata No 2 in D minor, Op 121 Vitazoslav Kubicka (1953-) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Winter Stories from the Forest, op 251, symphonic suite Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Adrian Kokos (conductor) 01:46 AM Cesar Franck (1822-1890) 05:21 AM Violin Sonata in A Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Seven Elegies (No 2, All' Italia) Valerie Tryon (piano) 02:15 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) 05:29 AM Adagio, from 'Violin Sonata No 33 in E flat, K 481' (encore) Vitezslav Novak (1870-1949) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) V Tatrach (In the Tatra mountains) - symphonic poem (Op.26) BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Richard Hickox (conductor) 02:23 AM Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) 05:46 AM Symphony No 3 in C minor, Op 44 Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971) Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Riccardo Chailly (conductor) Concertino for string quartet Apollon Musagete Quartet 03:01 AM Dora Pejacevic (1885-1923) 05:53 AM Symphony No 1 in F sharp minor, Op 41 Thomas Kessler (b.1937) Croatian Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, Mladen Lost Paradise Tarbuk (conductor) Camerata Variabile Basel 03:46 AM 06:08 AM John Browne (fl.1490) Bela Bartok (1881-1945), Arthur Willner (arranger) O Maria salvatoris mater (a 8) Romanian folk dances (Sz.56) arr. -

Peter Handke's Theatrical Works Scott Abbott, Utah Valley University

Utah Valley University From the SelectedWorks of Scott Abbott 1992 Peter Handke's Theatrical Works Scott Abbott, Utah Valley University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/scott_abbott/84/ 1 PETER HANDKE (6 December 1942- ) Scott Abbott [Dictionary of Literary Biography, Twentieth-Century German Dramatists , 1992] PLAY PRODUCTIONS : Publikumsbeschimpfung , Frankfurt/M., Theater am Turm, 8 June 1966, director: Claus Peymann; Weissagung and Selbstbezichtigung , Oberhausen, Städtische Bühnen, 22 October 1966, director: Günther Büch; Hilferufe , Stockholm (by actors from the Städtische Bühnen, Oberhausen), 12 September 1967; subsequently in Oberhausen on 14 October 1967, director: Günther Büch; Kaspar , Frankfurt/M., Theater am Turm, director: Claus Peymann, and Oberhausen, Städtische Bühnen, director: Günther Büch, 11 May 1968; Das Mündel will Vormund sein , Frankfurt/M., Theater am Turm, 31 January 1969, director: Claus Peymann; Quodlibet , Basel, Basler Theater, 24 January 1970, director: Hans Hollmann; Der Ritt über den Bodensee , Berlin, Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer, 23 January 1971, directors: Claus Peymann, Wolfgang Wiens; 2 Die Unvernünftigen sterben aus , Zürich, Theater am Neumarkt, 17 April 1974, director: Horst Zankl; Über die Dörfer , Salzburg, Salzburger Festspiele, 8 August 1982, director: Wim Wenders; Das Spiel vom Fragen oder die Reise zum sonoren Land , Vienna, Burgtheater, January 1990, director: Claus Peymann; Die Stunde da wir nichts voneinander wußten , Vienna, Theater an der Wien, 9 May 1992, director: Claus Peymann; -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

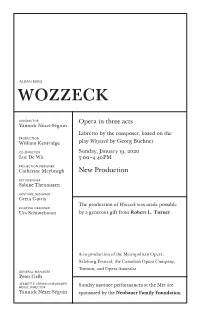

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J.