Journal of Psychopathology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Análisis Valorativo De Papel Desempeñado Por Atletas

Universidad de Matanzas “Sede Camilo Cienfuegos” Facultad de Ciencias de la Cultura Física ANÁLISIS VALORATIVO DEL PAPEL DESEMPEÑADO POR LOS ATLETAS MATANCEROS EN LOS JUEGOS OLÍMPICOS DE LA ERA MODERNA Trabajo de Diploma para optar por el título de Licenciado en Cultura Física Autor: Earduin Peñalver López. Tutora: MS.c María Felicia Ibáñez Matienzo. Consultante: MS.c Adelina López Arteaga. Matanzas, 2017 NOTA DE ACEPTACIÓN ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ _________________________ _______________________ Presidente Secretario _________________________ _____________________ Vocal Oponente Dado en Matanzas el ____ de _____________________ del 2017. PENSAMIENTO Los atletas retirados no son poseedores de riquezas materiales, pero son dueños de una patria sin amos, que los admira y los recordará siempre. El mejor estímulo que puede crearse para el atleta es asegurarle su retiro y saber premiar a los que llegan a ser Campeones. Fidel Castro Ruz -

Ranking Nacional 2011

RANKING NACIONAL DE ATLETISMO Elaborado por: Lic. Alfredo Sánchez Barrios (ATFS) CUBA 2011 DPTO.ESTADISTICA DEPORTIVA - CINID - INDER 1 MASCULINO 100 metros Resultado Viento Nombre y Apellido Prov. Año Nac. Lugar Ciudad Fecha Mejor Año RNA 9.98A 0.6 Silvio Leonard CFG 1955 1 Guadalajara 11/08/77 RNJ 10.24 0.6 Silvio Leonard CFG 1955 1 Praga 04/09/73 RNC 10.35A Francisco Fuentes SCU 1970 1ht Ciudad de México 19/06/87 10.27 -3.3 Michael Herrera ART 1985 1 La Habana 17/03 10.16 2009 10.28 0.9 David Lescay SCU 1989 1 Barquisimeto 27/07 10.20 2009 10.42 -3.3 Yadier Luis CMG 1989 2 La Habana 17/03 10.63 2009 10.51 -3.3 Yaniel Carrero SSP 1995 3 La Habana 17/03 10.53 -3.3 Manuel A. Ramírez HOL 1992 4 La Habana 17/03 10.59 2009 10.55 0.0 Víctor A. González HAB 1987 3 La Habana 24/06 10.25 2009 10.62 0.2 Orlando Ortega ART 1991 1h2 Camagüey 05/03 10.74 2009 10.68A 1.6 Yordani García PRI 1988 Dec Guadalajara 24/10 10.60 2009 10.76 -0.1 Yoisel Pumariega MTZ 1988 2h3 Camagüey 05/03 10.94 2007 10.77 -3.3 Rubén R. Caballero HAB 1994 5 La Habana 17/03 (10) 10.79 1.6 Yoandys A. Lescay LTU 1994 2h4 Camagüey 05/03 10.79 nwi Reynier Mena HAB 1996 1 Santiago de Cuba 09/07 10.81 0.2 Alejandro Herrera PRI 1991 3h2 Camagüey 05/03 10.59 2009 10.84 -1.6 Jhoanis C. -

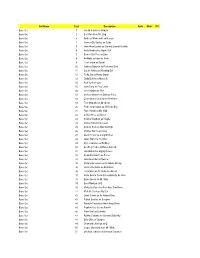

Presenze Tecnici Consglio Nazionale Geometri E G. L. Fino Al 18 Giugno 2017

Presenze Tecnici Consglio Nazionale Geometri e G. L. fino al 18 giugno 2017 ID Periodo di attività n° N° Prog. Nome Cognome Cellulare E-mail n° giorni totali tipologia attività Note tesserino dal al giorni 1 GIUSEPPE ABALSAMO 3771065224 [email protected] 31/01/2017 07/02/2017 8 FAST 16 2 GIUSEPPE ABALSAMO 3771065224 [email protected] 08/02/2017 15/02/2017 8 FAST 3 GIUSEPPE ABATE 3461327983 [email protected] 04/10/2016 11/10/2016 8 AEDES 4 SALVATORE ABBATE 3287672551 [email protected] 29/11/2016 06/12/2016 8 FAST 5 Carmine ABIUSO 337/912097 [email protected] 07/02/2017 14/02/2017 8 FAST 6 BARTOLO ABRATE 3463012362 [email protected] 27/09/2016 04/10/2016 8 AEDES 7 1271 ANDREA ABRUZZO 3286996563 [email protected] 06/09/2016 13/09/2016 8 AEDES 8 VITTORIO ACONE 3933301215 [email protected] 31/01/2017 09/02/2017 10 FAST 9 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 06/12/2016 13/12/2016 8 FAST 10 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 14/12/2016 18/12/2016 5 FAST 11 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 24/01/2017 07/02/2017 15 FAST 64 12 6610 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 02/03/2017 14/03/2017 13 FAST 13 5535 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 29/03/2017 06/04/2017 9 FAST 14 5535 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 04/04/2017 11/04/2017 8 FAST 15 5535 NICOLA ACUCELLA 3389497454 [email protected] 19/06/2017 24/06/2017 6 FAST 16 SALVATORE ADDAMO 328/0954883 [email protected] -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

40 Spring St., Lodi, NJ 07644

DECEMBER 29, 2019 40 Spring St., Lodi, NJ 07644 (973) 779-0643 [email protected] stjosephchurchlodi.org Rectory: 9am - 4pm MASS INTENTIONS MINISTERS’ SCHEDULE DECEMBER 28 & 29 JANUARY 4 & 5 TH SATURDAY, DECEMBER 28 LECTOR EMHC LECTOR EMHC 5:00 pm James DeGregory r/b wife and family SATURDAY, 5:00 PM SATURDAY, 5:00 PM SUNDAY, DECEMBER 29TH Roy 7:30 am Natalie Dennis r/b Rosina Taranto Lily Arañez Malorie 9:30 am Maria Antonina DiPeri r/b Campbell and Sinagra TBD TBD Scarcella Marlon Families Jean 11:30am Pietro LaFrancesca r/b Rosa Brancato Roby 5:00 pm Paula LaFranca r/b husband and children SUNDAY, 7:30 AM: SUNDAY, 7:30 AM: MONDAY, DECEMBER 30TH Mildred Tucci Barbara 5:30 am Basilisa Verdote r/b daughter, Corazon Verdote TBD TBD King Charles 12:00nn Peter & Anna Tront and Lorraine & Pay Ann Leovi Comeleo r/b Vincent & James Comeleo SUNDAY, 9:30 AM: SUNDAY, 9:30 AM: TUESDAY, DECEMBER 31ST M Riccobono Pitocco S Riccobono 7:00 am Juana Villagran r/b Dr. & Mrs. Ciro Carafa TBD TBD Mirante M Maggiore 12:00pm Margarita Capili r/b Capili family D LaSpisa 5:00 pm In reparaon, conversions, healings, restoraon and SUNDAY, 11:30 AM: SUNDAY, 11:30 AM: blessings in thanksgiving for D.A.D. & family r/b Maria Kathy WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 1ST; SOLEMNITY OF MARY, THE Sandra Lino HOLY MOTHER OF GOD R A HOLY DAY OF OBLIGATION Rommel Jean-Pierre TBD TBD 12:00pmAnna & Joseph Scimeca r/b daughter, Connie & Ongteco Erlinda Grandchildren Falcon 7:00 pm Thanksgiving of Falcon DeGuzman and family Jimena SUNDAY, 5:00 PM SUNDAY, 5:00 PM ND THURSDAY, JANUARY 2 Gayle 7:00 am For the parishioners & all those enrolled in St. -

BY APPOINTMENT ONLY. STRICTLY NO WALK-INS All Consular Service Applicants Are Reminded of the Following

CONSULAR OUTREACH PROGRAM 8 to 9 April 2017 First Filipino Methodist Church (Multi‐Purpose Building) 8603 South Kirkwood Road, Houston, TX 77099 BY APPOINTMENT ONLY. STRICTLY NO WALK-INS All Consular Service applicants are reminded of the following: • Arrive at least 30 minutes before their time of schedule • The Consular Outreach Team reserves the right to cancel any appointment made because the applicant failed to bring all original documents or his/her application was made through a non-relative or the conduct of the applicant, his/her relative/agent is detrimental to the consular service. APPOINTMENT SCHEDULE PASSPORT RENEWAL NEW PASSPORTS WILL BE RELEASED TO THE APPLICANT BY MAIL TWELVE (12) TO SIXTEEN (16) WEEKS FROM 12 APRIL 2017 OR LONGER IF SUBJECT TO DFA MANILA’S SECONDARY REVIEW. 1. Personal appearance is required in all cases (including applicants who are 65 years old and above and minors who are below 18 years old). 2. Do not bring passport pictures. 3. The applicant must wear decent attire (no sleeveless and/or collarless attire) and without eyeglasses/contact lenses. 4. No facial piercings allowed. EPASSPORT MOBILE EPASSPORT MOBILE EPASSPORT MOBILE #1 #2 #3 APRIL 8, 2017 (SATURDAY) 9:00am ‐10:00 am 1. LOCHNER, NORIELYN T. 2. SIMONI, MA. HAZEL V. 3. BEBIS, FLAVIO C. 4. MANLIGUEZ, ARCHIE G. 5. CACHUELA, ROLI C. 6. MAURICIO, RUFFHARELA D. 7. MANLIGUEZ, LALAINE M. 8. ALAPRIZ, ROMEO F. 9. CERVANTES, WILFRED L. 10. MANLIGUEZ, ANTHONY LAZARO M. 11. ALAPRIZ, VIRGINIA T. 12. PAGAYON, ALREDO JR G. 13. MANLIGUEZ, ALISTAIR M. 14. TALLMAN, FLORECITA ELENA Y. -

215Th Commencement 05302017

Greetings from the President May 30, 2017 Dear Graduates: Congratulations! You have reached a most significant milestone in your life. Your hard work, determination, and commitment to your education have been rewarded, and you and your loved ones should take pride in your accomplishments and successes. Hunter College certainly takes pride in you. Your Hunter education has prepared you to meet the challenges of a world that is rapidly changing politically, socially, economically, and technologically. As part of the next generation of thoughtful, responsible, and intelligent leaders, you will make a real difference wherever you apply your knowledge and skills. Endless opportunities await you. As you pursue your goals and move forward with your professional and personal lives, please carry with you Hunter's commitment to community, diversity, and service to otheq . We look forward to hearing great things about you, and we hope you will stay connected to the exciting activities and developments on campus. Please remember Hunter College and know that you will always be part of our family. Best wishes for continued success. f4ivtMSincerely, Jennifer J. Raab President 215th Commencement Exercises Presiding: Jennifer J. Raab President Eija Ayravainen Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean ofStudents Opening Ceremony Qin Lin Bachelor ofArts, '17 Processional President's Party and Members of the Faculty Candidates for Degrees National Anthem Carey Renee Anderson Master ofScience in Education, '17 Bagpiper Nicholas M. Rozak Bachelor ofArts, '07 Greetings Sandra Wilkin Board of Trustees of The City University ofNew York Chika Onyejiukwa Student Member, Board of Trustees of The City University ofNew York Charge to the Graduates President Jennifer J. -

Commencement Program

Sunday, the Sixteenth of May, Two Thousand and Ten ten o’clock in the morning ~ wallace wade stadium Duke University Commencement ~ 2010 One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement Notes on Academic Dress Academic dress had its origin in the Middle Ages. When the European universities were taking form in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, scholars were also clerics, and they adopted Mace and Chain of Office robes similar to those of their monastic orders. Caps were a necessity in drafty buildings, and Again at commencement, ceremonial use is copes or capes with hoods attached were made of two important insignia given to Duke needed for warmth. As the control of universities University in memory of Benjamin N. Duke. gradually passed from the church, academic Both the mace and chain of office are the gifts costume began to take on brighter hues and to of anonymous donors and of the Mary Duke employ varied patterns in cut and color of gown Biddle Foundation. They were designed and and type of headdress. executed by Professor Kurt J. Matzdorf of New The use of academic costume in the United Paltz, New York, and were dedicated and first States has been continuous since Colonial times, used at the inaugural ceremonies of President but a clear protocol did not emerge until an Sanford in 1970. intercollegiate commission in 1893 recommended The Mace, the symbol of authority of the a uniform code. In this country, the design of a University, is made of sterling silver throughout. gown varies with the degree held. The bachelor’s Significance of Colors It is thirty-seven inches long and weighs about gown is relatively simple with long pointed Colors indicating fields of eight pounds. -

Self-Reported Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Among Informal

Wulff et al. BMC Health Services Research (2020) 20:1114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05964-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety among informal caregivers of persons with dementia: a cross-sectional comparative study between Sweden and Italy Joseba Wulff1, Agneta Malmgren Fänge1 , Connie Lethin1,2* and Carlos Chiatti1 Abstract Background: Around 50 million people worldwide are diagnosed with dementia and this number is due to triple by 2050. The majority of persons with dementia receive care and support from their family, friends or neighbours, who are generally known as informal caregivers. These might experience symptoms of depression and anxiety as a consequence of caregiving activities. Due to the different welfare system across European countries, this study aimed to investigate factors associated with self-reported depression and anxiety among informal dementia caregivers both in Sweden and Italy, to ultimately improve their health and well-being. Methods: This comparative cross-sectional study used baseline data from the Italian UP-TECH (n = 317) and the Swedish TECH@HOME (n = 89) studies. Main outcome variables were the severity of self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). HADS scores were investigated using descriptive and bivariate statistics to compare means and standard deviations. Linear regressions were used to test for associations between potential factors and self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Results: Italian informal caregivers reported more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety than Swedish caregivers. In Italy, a higher number of hours of caregiving was associated with anxiety symptoms (β = − 1.205; p = 0.029), being 40–54 years-old with depression symptoms (β = − 1.739; p = 0.003), and being female with symptoms of both depression (β = − 1.793; p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 1.474; p = 0.005). -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

Film # Year Rec Name Father Mother Bride Father Mother 1883485 1897

www.SicilianFamilyTree.com Sant'Elia Fiumerapido Marriages 2/12/2013 Film # year Rec Name Father Mother Bride Father Mother 1883485 1897 22 D'Agostino, Giovanbattista Giovanbattista D'Agostino Lanni, Giuseppa AngeloSanto, Annunziata 1173821 1811 11 D'Agostino, Benedetto Michele D'Agostino fallone, Giovanna Angelosanto, Felice 1173821 1816 5 D'Agostino, AngeloSanto Pasquale D'Agostino Leo, Benedetta Angelosanto, Margherita 1883484 1872 5 Vettraino, Vincenzo Donato Vettraino Soave, Caterina Bastianello, Patrizia 1883485 1885 15 Vettraino, Alessandro Antonino Vettraino Placido, Giuseppa C ocorocchio, Vittoria 1173822 1833 19 D'Agostino, Giovanbattista Pasquale D'Agostino Felice, Rosa Caccone, Maria Anotnina 1883485 1893 18 Vettraino, Giovanni Francesco Vettraino ? Cascardero, Antonina 1173823 1853 21 D'Agostino, Alessandro Angelo D'Agostino Di Rocco, ? Cece, Carolina 1173821 1815 16 D'Agostino, Angelo Giuseppe D'Agostino Rupa, Angelica Cicco, Teresa 1883485 1897 36 D'Agostino, Giulio Pietro D'Agostino Lanili, alessandra Copataccio, Maria 1173823 1858 10 D'Agostino, Pietro Saverio D'Agostino Romano, Grazia Corsi, Giovanna 1173823 1851 6 D'Agostino, Rosato Antonino DonatoFelice D'Agostino Ropi, Francesca Cuozzo, Giovanna 1883485 1881 12 Violo, Antonino D'Agostino Concetta Pietro D'Agostino Corsi, Giovanna 1883485 1881 16 Morelli, Rosata D'Agostino Maria Grazia Biagio D'agostino Merucci, Palma 1883485 1892 37 Perschici, Giuseppe D'Agostino, Alessandra Antonino D'Agostino Rossi, Antonina 1173823 1851 7 Romolillo, Achille D'Agostino, Alessandra -

CUBA - Ranking U20 De Todos Los Tiempos Cierre: 09.07.2020 Compilado Por: Alfredo Sánchez (ATFS) Y Néstor Calixto MASCULINO Rank Tiempo W Atleta F.Nac

CUBA - Ranking U20 de todos los tiempos Cierre: 09.07.2020 Compilado por: Alfredo Sánchez (ATFS) y Néstor Calixto MASCULINO Rank Tiempo W Atleta F.Nac. Pos. Ciudad Fecha 100m 1 10.14 +1.9 Jenns R. Fernández 04.01.2001 2 La Habana 07.06.2019 2 10.17 +0.4 Reynier Mena 21.11.1996 1 Edmonton 31.07.2015 3 10.22 +1.9 Arnaldo L. Romero 05.04.2000 5 La Habana 07.06.2019 4 10.24 +0.6 Silvio Leonard 20.09.1955 1 Praga 04.09.1973 5 10.25 Joel Isasi 31.07.1967 1h Ciudad de México 26.06.1986 6 10.27 +1.3 Misael Ortiz 04.11.1978 1 La Habana 05.07.1997 7 10.28 +0.9 Yaniel Carrero 17.08.1995 3 Xalapa 25.11.2014 8 10.29 +0.7 Roberto Skyers 12.11.1991 1r2 Belém 19.05.2010 9 10.34 +1.8 César Y. Ruiz 18.01.1995 5r2 La Habana 27.06.2014 10 10.35 Francisco Fuentes 30.08.1970 1h Ciudad de México 19.06.1987 11 10.35 +1.4 Shainer Reginfo 08.04.2002 1rB La Habana 07.06.2019 12 10.38 José C. Peña 18.07.1982 1 Santiago de Cuba 04.07.2001 13 10.38 +1.6 Edel R. Amores 05.10.1998 2h1 La Habana 15.03.2017 14 10.39 Leonardo Prevost 13.06.1971 1 Orlando FL 20.07.1990 15 10.39 +1.7 Reidis Ramos 21.07.1996 2 Camagüey 15.05.2015 16 10.40 Carlos Y.