The Reverse of the Sublime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Gallery: Global Eyes Global Gallery: Art 152 ART GALLERY ELECTRONIC ART & ANIMATION CATALOG Adamczyk Walt J

Art Gallery: Global Eyes Chair Vibeke Sorensen University at Buffalo Associate Chair Lina Yamaguchi Stanford University ELECTRONIC ART & ANIMATION CATALOG ELECTRONIC ART & ANIMATION ART GALLERY ART 151 Table of Contents 154 Art Gallery Jury & Committee 176 Joreg 199 Adrian Goya 222 Masato Takahashi 245 Andrea Polli, Joe Gilmore 270 Peter Hardie 298 Marte Newcombe 326 Mike Wong imago FACES bogs: Instrumental Aliens N. falling water Eleven Fifty Nine Elevation #2 156 Introduction to the Global Eyes Exhibition Landfill 178 Takashi Kawashima 200 Ingo Günther 223 Tamiko Thiel 246 Joseph Rabie 272 Shunsaku Hayashi 327 Michael Wright Running on Empty Takashi’s Seasons Worldprocessor.com The Travels of Mariko Horo Psychogeographical Studies Perry’s Cowboy • Animation Robotman Topography Drive (Pacific Rim) Do-Bu-Ro-Ku 179 Hyung Min Lee 224 Daria Tsoupikova 158 Vladimir Bellini 247 r e a Drought 328 Guan Hong Yeoh Bibigi (Theremin Based on Computer-Vision Rutopia 2 La grua y la jirafa (The crane and the giraffe) 203 Qinglian Guo maang (message stick) 274 Taraneh Hemami Here, There Super*Nature Technology) A digital window for watching snow scenes Most Wanted 225 Ruth G. West 159 Shunsaku Hayashi 248 Johanna Reich 300 Till Nowak 329 Solvita Zarina 180 Steve Mann ATLAS in silico Ireva 204 Yoichiro Kawaguchi De Vez En Cuando 276 Guy Hoffman Salad See - Buy - Fly CyborGLOGGER Performance of Hydrodynamics Ocean Time Bracketing Study: Stata Latin 226 Ming-Yang Yu, Po-Kuang Chen 250 Seigow Matsuoka Editorial 301 Jin Wan Park, June Seok Seo 330 Andrzej -

Steuernummer Mit Peter Absprechen

Tamiko Thiel [email protected] www. tamikothiel.com Biography Tamiko Thiel was awarded the 2018 iX Immersive Experiences Visionary Pioneer Award for her life work by the Society for Art and Technology Montreal. Born in 1957, she is a visual artist exploring the interplay of place, space, the body and cultural identity in works encompassing a supercomputer, objects, installations, digital prints in 2D and 3D, videos, interactive 3d virtual worlds (VR), augmented reality (AR) and artificial intelligence (AI). Thiel received her B.S. in 1979 from Stanford University in Product Design Engineering, with an emphasis on human factors. She received her M.S. in Mechanical Engineering in 1983 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), with a focus on human-machine design at the Biomechanics Lab and computer graphics at the precursors to the MIT Media Lab. She then earned a Diploma (Master of Arts equivalent) in Applied Graphics in 1991 from the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Germany, specializing in video installation art. Her first artwork, the visual design for the Connection Machine CM-1/CM-2 artificial intelligence supercomputer (1986/1987, and in 1989 the fastest machine in the world) is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art New York and the Smithsonian Institution. She began working with virtual reality in 1994 as creative director and producer of the Starbright World (1994-1997) online VR playspace for seriously ill children, in collaboration with Steven Spielberg, and her VR artwork Beyond Manzanar (2000, with Zara Houshmand), has been in the collection of the San Jose Museum of Art in Silicon Valley since 2002. -

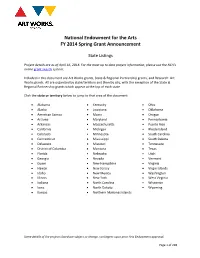

Spring 2014--All Grants Sorted by State

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2014 Spring Grant Announcement State Listings Project details are as of April 16, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Included in this document are Art Works grants, State & Regional Partnership grants, and Research: Art Works grants. All are organized by state/territory and then by city, with the exception of the State & Regional Partnership grants which appear at the top of each state. Click the state or territory below to jump to that area of the document. • Alabama • Kentucky • Ohio • Alaska • Louisiana • Oklahoma • American Samoa • Maine • Oregon • Arizona • Maryland • Pennsylvania • Arkansas • Massachusetts • Puerto Rico • California • Michigan • Rhode Island • Colorado • Minnesota • South Carolina • Connecticut • Mississippi • South Dakota • Delaware • Missouri • Tennessee • District of Columbia • Montana • Texas • Florida • Nebraska • Utah • Georgia • Nevada • Vermont • Guam • New Hampshire • Virginia • Hawaii • New Jersey • Virgin Islands • Idaho • New Mexico • Washington • Illinois • New York • West Virginia • Indiana • North Carolina • Wisconsin • Iowa • North Dakota • Wyoming • Kansas • Northern Marianas Islands Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 228 Alabama Number of Grants: 5 Total Dollar Amount: $841,700 Alabama State Council on the Arts $741,700 Montgomery, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: State & Regional To support Partnership Agreement activities. Auburn University Main Campus $55,000 Auburn, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: Visual Arts To support the Alabama Prison Arts and Education Project. Through the Department of Human Development and Family Studies in the College of Human Sciences, the university will provide visual arts workshops taught by emerging and established artists for those who are currently incarcerated. -

Beyond Manzanar

Beyond Manzanar interactive virtual reality installation by Tamiko Thiel and Zara Houshmand 2000 Background Material http://mission.base.com/manzanar/ Beyond Manzanar - In the Wake of Sept. 11th We started Beyond Manzanar in 1995 in response to blind attacks on people of Middle Eastern extraction after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, when the media erroneously linked the bombing to the Middle East. In a disturbing sort of deja vu, there is now a wave of attacks and death threats against people who look Muslim or of Middle Eastern extraction - even though many came to the west as refugees from the regimes they are accused of representing. It goes far beyond damage to property: A Sikh was murdered in Mesa, Arizona, because he wore a turban. A Pakistani-American was murdered in Dallas. A British- Afgani in England was paralyzed from the neck down. Beyond Manzanar focuses on our own ethnic groups - Iranian American and Japanese American - but its message is universal. We depict attacks on Iranian Americans and calls for their internment during the 1979-'80 Iranian Hostage Crisis, putting them in the context of the media hysteria that led to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. With full support from President Roosevelt the US military claimed there was "military necessity" to intern over 120,000 men, women and children without due process and for no crime other than the fact of their Japanese ancestry. In 1985, Norman Mineta, then a Congressman and currently Secretary of Transportation, introduced H.R. 442, The Civil Liberties Act with the statement that ".. -

The Connection Machine

The Connection Machine by William Daniel Hillis M.S., B.S., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1981, 1978) Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 1985 @W. Daniel Hillis, 1985 The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author. Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science May 3, 1985 Certified byG Prc tsor Gerald Sussmnan, Thesis Supervisor Acceptd by 'hairman, Ifepartment Committee MASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE OF TECHNOL.OGY MAR 221988 I UDIWaS The Connection Machine by W. Daniel Hillis Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 3, 1985 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Someday, perhaps soon, we will build a machine that will be able to perform the functions of a human mind, a thinking machine. One of the many prob- lems that must be faced in designing such a machine is the need to process large amounts of information rapidly, more rapidly than is ever likely to be possible with a conventional computer. This document describes a new type of computing engine called a Connection Machine, which computes through the interaction of many, say a million, simple identical process- ing/memory cells. Because the processing takes place concurrently, the machine can be much faster than a traditional computer. Thesis Supervisor: Professor Gerald Sussman 2 Contents 1 Introduction 6 1.1 We Would Like to Make a Thinking Machine 6 1.2 Classical Computer Architecture Reflects Obsolete Assumptions 9 1.3 Concurrency Offers a Solution .. -

1 Thinking Machines Extended Labels Curatorial Asst. Giampaolo

Thinking Machines Extended labels During the twentieth century, punched or Hollerith cards, named after a designer who Curatorial Asst. innovated a mechanism for tabulating similar Giampaolo Bianconi cards during the 1890 United States census, ext. 6365 were indispensable for programming purposes and became ubiquitous in the computer industry. The punched holes in these cards, BM 2112-60 prepared using a keypunch machine, are cement gray switches: a hole means a signal is on, while solid paper means a signal is off. Complex programs required hundreds or thousands IBM of punch cards in a deck to operate. The cards Punch have a missing corner designed to prevent Cards them from being inserted into machines incorrectly. Punch-card technology dates from the nineteenth century, when a “chain of cards” was used to control the patterns woven by a Jacquard loom. Punch cards were gradually replaced with magnetic tape storage, and IBM stopped producing them in the mid-1980s. Hummingbird is one of the earliest computer- animated films by the artist and programmer Charles Csuri. To produce Hummingbird, over thirty thousand individual images generated by a computer were drawn directly on film using a microfilm plotter. “To facilitate control over the motion of some sequences,” Csuri explained, “the programs were written to read all the controlling parameters from cards, Charles Csuri, one card for each frame,” indicating just how Hummingbird labor-intensive early forms of computer animation could be. This film was acquired by the Museum in 1968, making it one of the earliest computer-generated artworks to enter the collection. Page: 1 Thinking Machines Extended labels This commercial programmable computer by Olivetti was designed as a desktop equivalent Curatorial Asst. -

Danny Hillis Interview – Connection Machine Legacy. August 23, 2016

Danny Hillis interview – Connection Machine Legacy. August 23, 2016 In this interview transcript, Tamiko Thiel interviews Danny Hillis, inventor of the Connection Machine and founder of Thinking Machines Corporation, on the work he and his fellow scientists did in the 1980s-90s and how that has influences contemporary parallel computing and artificial intelligence. (Tamiko Thiel was responsible for product design of the CM-1/CM-2: http://tamikothiel.com/cm ) General interest links on Danny and the Connection Machines CM-1/CM-2, and the CM-5: Danny's bio: http://longnow.org/people/board/danny0/ Connection Machine: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connection_Machine The Evolution of Thinking Machines / Aspen Insitute talk https://youtu.be/LxqgGMmmj8A Danny Hillis, Connection Machine Legacy: Sergey Brin/Google https://www.youtube.com/edit?video_id=roCJ6tcku60 TT: I was thinking, well it's 30 years since the machine was launched, a lot has changed in that time, at least in terms at least of what we can do with all the concepts for which the machine was invented. Hence my idea to start a project with sort of indefinite goals and timespan but just to at some level educate myself about what was happening in AI over the last 30 years. DH: OK, well to go back, one of the founding premises of Thinking Machines was that artificial intelligence would require parallel computers. And that’s sort of an obvious statement now but if you recall, there were a lot of people who believed that there were proofs that parallel computers could never work. And the reason that I believed that they could, in spite of all the proofs, like you know, Amdahl’s Law and things like that, was that I knew that the brain works, and it used very slow components, but a lot of them, so clearly a lot of slow components working in parallel were good enough enough for the computations that we were having trouble with, like pattern recognition. -

Globalization, Media Arts, and the Possibility of Avant-Gardism in the Twenty-First Century

CHAPTER TWO: GLOBALIZATION, MEDIA ARTS, AND THE POSSIBILITY OF AVANT-GARDISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY I. Overview Chapter One investigated the presence of modern technology in the arts, paying particular attention to canonical art historical responses. The mixed reactions to media arts, especially as culled from writings of the late 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, range from unguarded enthusiasm to foreboding regarding technology’s fascistic potential. Still others overlook its significance altogether. This chapter, dedicated largely to developments in art and technology in the 1980s and 1990s, continues this line of discussion by analyzing the growing importance of video, and the onset of digital forms. In addition, the social reality of globalization (with its attendant diversification of subjectivities) will be highlighted as pivotal in the types of works being made. A diversity of artists, whose expressions often reject traditional forms, instead embrace ‘low’ or ‘mass’ media like video, projection art, and more recently, electronic and digital art. Looking back on earlier discussions as necessary, this section will consider the relationship between avant-garde practice, globalization, and the role of technology in shaping contemporary aesthetics. Descriptors like “democratic” and “avant-garde” have been associated with utopian constructions of what electronics and the digital might offer; namely, a “global village” realized. Meanwhile, its negative associations have linked the digital to electronic multinational corporate interests and economic globalization, often ideologically critiqued as a global hegemonic Westernization. Chapter Two contemplates the possibility of an avant-garde in the twenty-first-century, despite the supposedly deleterious influences of globalization, multinational capitalism, and 85 86 electronic media—elements that on the surface seem incongruous with the very definition of vanguardism. -

Oral History of Danny Hillis; 2008-09-05

Oral History of William Daniel (Danny) Hillis II Interviewed by: Gardner Hendrie Edited by: Dag Spicer Recorded: September 5, 2008 Glendale, California CHM Reference number: X4654.2009 © 2008 Computer History Museum Oral History of Danny Hillis Gardner Hendrie: Well, we have with us today Danny Hillis. He's gracefully given us the opportunity to do an oral history of him. Thank you very much, Danny. Danny Hillis: It's a pleasure. Hendrie: Okay. What I'd like to do maybe is start with a little bit of family background, things like where you grew up, what your mother and father did, siblings, get a feel for the environment in which you -- your early years. Hillis: Okay. Well, my father was an epidemiologist, so we basically spent my childhood going off to places where there were interesting epidemics going on, so I lived overseas a lot of my life in places like the Congo or Rwanda. I lived in Calcutta for a long time. Hendrie: Oh, my goodness. Hillis: So it was a fun environment to grow up in. By the time I was in sixth grade, I'd been to 12 different schools, so it was a pretty irregular education, and sometimes there really weren't good schools around where we were. I'd kind of get home-schooled, although we didn't call it that at the time. And so it was an odd way to grow up. I would say I had a scientific education, but it was biology, not engineering or anything like that. Hendrie: All right. -

Tamiko Thiel 14 Juri Street

Tamiko Thiel visual artist [email protected] www.tamikothiel.com C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E EDUCATION 1991 AKADEMIE der BILDENDEN KÜNSTE (Academy of Fine Arts), Munich, Germany. Fine Arts Diploma. Concentration on found object installations and video art installations. 1983 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY, Cambridge, MA, USA. M.S. in Mechanical Engineering. Studies in Biomechanics Lab and in precursor to MIT Media Lab. 1979 STANFORD UNIVERSITY, Stanford, CA, USA. B.S. in General Engineering/Product Design. Concentration in human-machine interface design. COLLECTIONS: MUSEUM of MODERN ART (MoMA), New York, NY. Connection Machine CM-2 WHITNEY MUSEUM of AMERICAN ART, New York, NY. Unexpected Growth AR installation SAN JOSE MUSEUM of ART, San Jose, Silicon Valley, California. Beyond Manzanar VR installation ROSE GOLDSEN ARCHIVE of NEW MEDIA ART, Cornell University, Cornell, USA. COMPUTER HISTORY MUSEUM, Silicon Valley, California. Connection Machine CM-1 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, Washington DC. Connection Machine CM-2 JULIA and ANTON HOFMEIER Collection, Nothing of Him That Doth Fade, ceramic 3D print, AR PEGGY and THOMAS WILL Collection, paintings from the Mountains series SELECTED AWARDS, RESIDENCIES, COMMISSIONS: 2020 FILM FERNSEH FONDS BAYERN (Film Commission Bayern) project development grant for a mixed reality VR installation on the elemental cycles of life. NANTESBUCH FOUNDATION commission for "Suspended Spring" video artwork, for the "Arts for Spring" online exhibition during the coronavirus crisis. “My Identity Is This Expanse,” commission as guest VR artist for this VR experience by Karolina Markiewicz and Pascal Piron, with funding from FILM FUND LUXEMBOURG. DiMoDA 4.0 commission for a VR artwork, curated by Christiane Paul. -

Life Attheinterface of Art and Technology

MEDIA arts WOMEN IN FILM Life at the Interface of Art and Technology By Tamiko Thiel When I was in college in the late 1970s, there were very few programs combining art and technology. I was taking classes in both areas but finding satisfaction in neither, until I found the Product Design program at Stanford University. Here one could take art, design and mechanical engineering classes toward a single major, and I felt like I had finally found a home for myself. In those days I was interested primarily in the engineering design of 3D products and especially in questions of the user interface: how the user approached, perceived, understood and then used the product. These questions have stayed with me in my evolution into an artist working with interactive 3D virtual worlds. My last engineering project was in the early 1980s at Thinking When I saw the wonder, delight and awe in the faces of those Machines, when Danny Hillis asked me to do the packaging who saw the finished machine, I understood for the first time the design for his Connection Machine CM-1/CM-2 supercomputer. power of images and objects to touch people deeply. We had I consider this machine also to be my first artwork, because tapped into an archetypal image of what an “electronic brain” in the process of coming up with a design that expressed the could be, and created a machine that evoked that image at a revolutionary nature of this massively parallel supercomputer time when most computers were as sexy as refrigerators.