Martin L. Perl 185

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The PLUTO Experiment at DORIS (DESY) and the Discovery of the Gluon (A Recollection]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8568/the-pluto-experiment-at-doris-desy-and-the-discovery-of-the-gluon-a-recollection-478568.webp)

The PLUTO Experiment at DORIS (DESY) and the Discovery of the Gluon (A Recollection]

(9.46 GeV) and the gluon discovery (a critical recollection of PLUTO results)* Bruno R. Stella1,a and Hans-Jürgen Meyer2,b 1 Department of Physics of Roma Tre University and INFN; Rome, Italy 2 formerly at Department of Physics, Siegen University; Siegen, Germany Abstract. The hadronic decays of (9.46 GeV) were first studied by the PLUTO experiment at the DORIS e+e- storage ring (DESY). With the aim of determining the contribution of PLUTO to the discovery of the gluon, as members of this former collaboration we have reconsidered all the scientific material produced by PLUTO in 1978 and the first half of 1979. It results clearly that the experiment demonstrated the main decay of the (9.46 GeV) resonance to be mediated by 3 gluons, by providing evidence for the agreement of this hypothesis with average values and differential distributions of all possible experimental variables and by excluding all other possible alternative models. Jettiness resulted evident by the average transverse momentum <pT> with respect to the event thrust axis, which was the same as experimentally observed by PLUTO itself at nearby continuum c.m.s. energies for 2-quark jet events. On the contrary, the average sphericity <S> and more topological variables as well as the momentum distribution showed a net difference with the same data comparison, a result compatible with jettiness only in case of more than 2 jets. Flatness as consequence of a 3-body decay (therefore 3 jets) was indicated by the low average momentum out of the event plane <pout>, altogether a result being independent of models. -

Jet Production and High Pt Phenomena in Photon-Photon Reactions*

JET PRODUCTION AND HIGH PT PHENOMENA IN PHOTON-PHOTON REACTIONS* NORBERT WERMES ~" Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 ABSTRACT The status of experimental investigations of high PT phenomena and jet production in photon- photon collisions is reviewed. Taking the challenging questions on hard scattering processes in ~/ff reactions as a guide, the experimental approach to these questions is summarized. Results from the PETRA experiments CELLO, JADE, PLUTO, and TASSO are presented including preliminary results on the Q2-dependence of jet cross sections. Experimental limitations and background problems are discussed. Zusammenfassung -- Es wird ein Uberblick fiber den Stand experimenteller Untersuchungen yon high-PT Ph~nomenen und der Erzeugung von Jets in Photon-Photon Wechselwirkungen gegeben. Anhand der herausfordernden Fragen beziiglich harter Streuprozesse in ~/ff Reaktionen wird der experimentelle Ansatz zur Beantwortung dieser Fragen zusammengefasst. Ergebnisse der PETRA Experimente CELLO, JADE, PLUTO und TASSO werden presentiert. Vorli~ufige Untersuchungen der Q2-Abh~ngigkeit von Jet-Wirkungsquerschnitten sowie experimentelle Einschr~nkungen und Untergrundprobleme werden diskutiert. * Work supported by the Department of Energy, contract DE-AC03-76SF00515. ? Alexander yon Humboldt Fellow. 120 1. INTRODUCTION This talk reviews experimental results on hard scattering reactions in qff collisions via high PT phenomena. The talk is divided into three parts. First I shall try to list the physics challenges for photon- photon experiments, in the context of hard scattering processes at high PT. In the main part the experimental approach to these challenging questions is discussed. It will be explained why we believe that hard scattering processes do exist. Then the explicit jet-searches performed by the different experiments are reviewed. -

A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) JETS AND QCD: A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets and its Impact on QCD⋆ A.Ali1 and G.Kramer2 1 DESY, D-22603 Hamburg (Germany) 2 Universit¨at Hamburg, D-22761 Hamburg (Germany) Abstract. The observation of quark and gluon jets has played a crucial role in establishing Quantum Chromodynamics [QCD] as the theory of the strong interactions within the Standard Model of particle physics. The jets, narrowly collimated bundles of hadrons, reflect configurations of quarks and gluons at short distances. Thus, by analysing energy and angular distributions of the jets experimentally, the properties of the basic constituents of matter and the strong forces acting between them can be explored. In this review, which is primarily a description of the discovery of the quark and gluon jets and the impact of their obser- vation on Quantum Chromodynamics, we elaborate, in particular, the role of the gluons as the carriers of the strong force. Focusing on these basic points, jets in e+e− collisions will be in the foreground of the discussion and we will concentrate on the theory that was contempo- rary with the relevant experiments at the electron-positron colliders. In addition we will delineate the role of jets as tools for exploring other particle aspects in ep and pp/pp¯ collisions - quark and gluon densi- ties in protons, measurements of the QCD coupling, fundamental 2-2 quark/gluon scattering processes, but also the impact of jet decays of top quarks, and W ±, Z bosons on the electroweak sector. -

Sensitivity Physics. D KAONS, Or

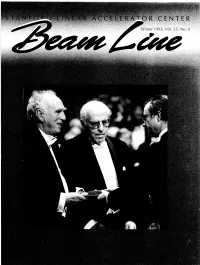

A PERIODICAL OF PARTICLE PHYSICS WINTER 1995 VOL. 25, NUMBER 4 Editors RENE DONALDSON, BILL KIRK Contributing Editor MICHAEL RIORDAN Editorial Advisory Board JAMES BJORKEN, GEORGE BROWN, ROBERT N. CAHN, DAVID HITLIN, JOEL PRIMACK, NATALIE ROE, ROBERT SIEMANN Illustrations page 4 TERRY ANDERSON Distribution CRYSTAL TILGHMAN The Beam Line is published quarterly by the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, PO Box 4349, Stanford, CA 94309. Telephone: (415) 926-2585 INTERNET: [email protected] FAX: (415) 926-4500 Issues of the Beam Line are accessible electronically on uayc ou the World Wide Web at http://www.slac.stanford.edu/ pubs/beamline/beamline.html SLAC is operated by Stanford University under contract with the U.S. Department of Energy. The opinions of the authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Cover: Martin Perl (left) and Frederick Reines (center) receive the 1995 Nobel Prize in physics from His Majesty the King of Sweden at the awards ceremony last December. (Photograph courtesy of Joseph Peri) Printed on recycled paper tj) . CONTENTS FEATURES "We conclude that the signature e-/. events cannot be explained either by the production and decay of any presently known particles 4 Discovery of the Tau or as coming from any of the well- THE ROLE OF MOTIVATION & understood interactions which can TECHNOLOGY IN EXPERIMENTAL conventionally lead to an e and a PARTICLE PHYSICS gu in the final state. A possible ex- One of this year's Nobel Prize in physics planation for these events is the recipients describes the discovery production and decay of a pair of of the tau lepton in his 1975 new particles, each having a mass SLAC experiment. -

Where Are We in Particle Physics? by S

Where are we in particle physics? by S. B. Treiman Technologically on course — installation of superconducting magnets below the Fermilab main ring. (Photo Fermilab) The fourth in a series of HEPAP (High Energy Physics Advisory Panel) Sub- panels, formed from time to time to review the status of the US high ener gy physics programme, last year had to confront an unusually wide array of opportunities and problems. The scientific opportunities and chal lenges are well known. They spring from the prodigious experimental and theoretical strides of the past decade and lay out the case for a new round of accelerator and other facili ties — to pursue the critical leads opened up by the recent develop ments and, as always, to allow for the unexpected. A number of delicious possibili ties, in various stages of definition, were in view: the Stanford Linear Collider for electron-positron phy sics at 100 GeV centre-of-mass en ergy; a Cornell conception for an el ectron-positron collider at a similar energy, based on superconducting r.f. technology; possible electron- proton collider facilities, etc. Nev traditional place. tion that we may be almost 'there' is ertheless, the prevailing climate was The current difficulties seem to be of course risky, if not outrageous, such as to focus attention mainly on mainly fiscal and technological ; there and even the most forward of the the problems. The problems are also are also problems, shared with Eu proponents of this view qualify it in well known — the financial ones, rope, associated with the complex various ways. which increasingly constrain the pro sociology of the large collaborations Everyone acknowledges that there gramme and utilization of existing that are increasingly called for in high are crucial tests to be made and facilities and the technological ones, energy experimentation. -

The Pluto Experiment at Doris (Desy) And

THE PLUTO EXPERIMENT AT DORIS (DESY) AND THE DISCOVERY OF THE GLUON. (A RECOLLECTION). Bruno R. Stella1 Department of Physics of Roma Tre University and INFN; Rome, Italy Hans-Jürgen Meyer2 formerly at Department of Physics, Siegen University; Siegen, Germany (to be submitted to The European Physical Journal H) Abstract. With the aim of determining the contribution of the PLUTO experiment at the DORIS e+e- storage ring to the discovery of the gluon, as members of this former collaboration we have reconsidered all the scientific material produced by PLUTO in 1978 and the first half of 1979. It is clear that the experiment demonstrated the main decay of the Y(9.46 GeV) resonance to be mediated by 3 gluons, by providing evidence for the agreement of this hypothesis with average values and differential distributions of all possible experimental variables and by excluding all other possible alternative models. Moreover PLUTO measured in June 1979 the matrix element of the 3-gluon decay to be quantitatively as expected by QCD (even after hadronization) and, having checked the possibility to correctly trace the gluons’ directions, demonstrated the spin 1 nature of the gluon by excluding spin 0 and spin ½. The hadronization of the gluon like a quark jet, hypothesized in the 3-gluon jet Monte Carlo simulation, was compatible with the topological data at this energy and was shown to -1 be an approximation at 10% level for the multiplicity (≈<p||> ); the right expected gluon fragmentation was needed for the inclusive distributions; this was the first experimental study of (identified) gluon jets. -

Discovery of the Tau the Role of Motivation & Technology In

One of this year’s Nobel Prize in physics recipients describes the discovery of the tau lepton in his 1975 SLAC experiment. Discovery of the Tau The Role of Motivation & Technology in Experimental Particle Physics by Martin L. Perl HERE HAVE BEEN SEVERAL chronological descriptions of the discovery of the tau lepton, Perl1,2 Feldman.3 In this Tarticle I take a different approach, I compare the discov- ery of the tau with the discovery of the other leptons: electron, muon, electron neutrino, and muon neutrino. My purpose is to illustrate the roles of motivation and of scientific technology in experimental el- ementary particle physics. I do not intend this article to be a thorough recounting or examination of the histories of lepton discoveries; I only discuss or reference those parts of the histories which are relevant to my purpose. 4 WINTER 1995 CATHODE RAYS AND THE ELECTRON’S DISCOVERY THE DISCOVERY OF THE ELECTRON was the result of almost a half cen- tury of experimental work and speculation on the nature of cathode rays.4 It was already known in the eighteenth century that an electrical voltage applied between conductors in a partially evacuated glass tube could pro- duce light. Inside the tube the gas glowed; the size and shape of the glowing region depended on the voltage, geometry, and pressure. By the 1870s it was recognized that in simple geometries the glowing region was caused by, or consisted of, rays which traveled in straight lines, with one end of the ray’s path at the cathode and the other at the anode. -

Jets and Qcd*

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) JETS AND QCD⋆ A.Ali1 and G.Kramer2 1 DESY, D-22603 Hamburg (Germany) 2 Universit¨at Hamburg, D-22761 Hamburg (Germany) Abstract. The observation of quark and gluon jets has played a crucial role in establishing Quantum Chromodynamics [QCD] as the theory of the strong interactions within the Standard Model of particle physics. The jets, narrowly collimated bundles of hadrons, reflect configurations of quarks and gluons at short distances. Thus, by analysing energy and angular distributions of the jets experimentally, the properties of the basic constituents of matter and the strong forces acting between them can be explored. In this review we summarise the properties of quark and gluon jets and the impact of their observation on Quantum Chro- modynamics, primarily the discovery of the gluons as the carriers of the strong force. Focusing on these basic points, jets in e+e− collisions will be in the foreground of the discussion. In addition we will delineate the role of jets as tools for exploring other particle aspects in ep and pp/pp¯ collisions - quark and gluon densities in protons, measurements of the QCD coupling, fundamental 2-2 quark/gluon scattering processes, but also the impact of jet decays of top quarks, and W ±, Z bosons on the electroweak sector. The presentation to a large extent is formulated in a non-technical language with the intent to recall the significant steps historically and convey the significance of this field also to communities beyond high energy physics. 1 Introduction Quantum Chromodynamics [QCD], the theory of the strong interactions within the Standard Model of particle physics [1,2], describes the building blocks of strongly interacting particles, like proton, neutron and many others, and the forces acting between them. -

The Discovery of the Tau Lepton and the Changes in Elementary Particle Physics in 40 Years

SLAC-PUB-10150 October 2003 Tau Discovery THE DISCOVERY OF THE TAU LEPTON AND THE CHANGES IN ELEMENTARY PARTICLE PHYSICS IN 40 YEARS Martin L. Perl Stanford Linear Accelerator Center and Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94309 Phone: 650-926-4286 Fax: 650-926-4001 Email: [email protected] Introduction This is a history of my discovery of the tau lepton in the 1970s for which I was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. I have previously described some aspects of the discovery. In 1996 in my collection of papers entitled, “Reflections on Experimental Science,”1 I gave a straightforward account of the experimental method and the physics involved in the discovery as an introduction to the collection. In a 2002 paper2 written with Mary A. Meyer published in the journal Theoria et Historia Scientiarum I used the story of the discovery to outline my thoughts on the practice of experimental science. That 2002 paper was written primarily for young women and men who are beginning their lives in science and it was based on a lecture given at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Some of the historical material in this paper has appeared in those two earlier papers. This history of the tau discovery has three goals. First, I want to give the history of the discovery. Second, I want to give a general picture of the high energy physics world of thirty to forty years ago. It was very different from today's world of high energy Submitted to Physics in Perspective *Work supported by Department of Energy contract DE-AC03-76SF00515. -

DESY Results from DORIS

Drawing of an electron-muon event as seen in the PLUTO detector on the DORIS storage rings at DESY. They have added important evidence for the existence of heavy leptons. decided within GESSS (Group for European Superconducting Systems Study) that Karlsruhe would construct and install two quadrupole magnets for the SPS experiment WA2 which looks at the leptonic decays of hyperons. Two quadrupoles are required in the beam line to match the characteristics of the hyperon beam emerging from a target bombarded by the primary proton beam to the acceptance of the experiment's spectrometer. Due to the short lifetimes of the hyperons, their Compact design of magnets and (less than 3 %) for hadron misiden- path lengths need to be kept short and cryostats has kept the outer (warm) tification. It seems that the only way to this calls for the use of high field super diameter to 24cm in the end parts, explain this class of events by the reac conducting magnets wherever possi which can thus slip between the coils tion is in terms of an interaction in ble. By avoiding iron pole tips, the of neighbouring normal dipole which the electron and positron give a quadrupoles provide focusing for magnets. In this way, the effective pair of heavy leptons which then decay hyperons up to 1 50GeV/c with a peak length required for focusing in the to the known leptons. The production field gradient of 1 60T/m in magnets of beam is below 2 m. cross section has a threshold around 4 overall length 1.4m and 1.1m. -

Recent E+E- Physics

KfK 2995 Juli 1980 Recent e+e- Physics G. Flügge Institut für Kernphysik Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe KERNFORSCHUNGS ZENTRUM KARLSRUHE Institut für Kernphysik KfK 2995 Recent e+ e - Physics Günter Flügge Lectures presented at the VIIIth International Winter Meeting on Fundamental Physics, Ronda, Spain, March 24-29, 1980 Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, Karlsruhe Als Manuskript vervielfältigt Für diesen Bericht behalten wir uns alle Rechte vor Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH ISSN 0303-4003 Recent e+ e - Physics Abstract Recent results from e+ e - storage rings are discussed, with empha- sis on PETRA experiments: total cross section and search for toponium; check of QED in e, ~ and T pair production; jet physics and evidence for gluon bremsstrahlung. Neuere e+ e - Physik Zusammenfassung Neuere Ergebnisse von e+e- Speicherringen werden diskutiert, mit Betonung der PETRA Experimente: totaler Wirkungsquerschnitt und Suche nach Toponium; Überprüfung der QED in e-, ~- und T-Paarproduktion; Jet-Physik und Evidenz für Gluon-Bremsstrahlun~. CONTENTS paqe I. INTRODUCTION 1 + - . 1. e e Storage Rlng~ 2 Petra 3 Detectors 7 2. Cross Sections 14 a) ~-Pair Production 14 b) BhabhaScattering 15 3. Hadron Production at Low Energies 11) Measurement of crhad below 5 GeV 17 Charm 19 11. THIRD GENERATION OF QUARKS AND LEPTONS 1. The Heawy Lepton T 22 2. The Bottom Quark b 22 Tota1 wi dth 26 T" at CESR 26 111. LEPTONIC PROCESSES 30 1. Test of QED 30 QED Check 30 2. Pointlike Structure of Leptons 32 IV. HIGH ENERGY HADRON PRODUCTION 37 1. Total Cross Section 37 Measurements 38 2. Jets in e+e- + hadrons 40 Jet Measures 42 Measurements 44 3. -

Physics Monitor

of mass. The global cosmic ray de eagerly awaited information on new Notwithstanding Landau's famous tection effort produces no more than mass scales. For example, each dif admonition: 'Cosmologists are often 300 events per year at this energy ferent type of proton decay mode wrong, but seldom in doubt' — cos and no more than 2000 events per would be associated with its own mology, while also exploring other year at 10 TeV in the centre of mass. mass scale. While decays producing intermediate mass scales, provides These numbers would increase ten one lepton would require a mass of our only window on masses beyond fold if there was a 100 km2 coverage 1014 GeV, other decays can be pro 1014 GeV. with detection devices — certainly posed, producing additional leptons, But, even after painting this bleak worthwhile until a 100 TeV acceler and the masses involved become picture for 'the experimental pros ator becomes available, but no sub lighter by many orders of magnitude. pects of particle physics, I am contin stitute for investment in new acceler All these decay modes could co ually and forever being amazed how ators and their design. exist though some of them might be relatively rapidly our experimental Non-accelerator experiments, in relatively rare. Thus proton decay colleagues succeed in demolishing cluding searches for proton decay, experiments will have a long life (or sometimes demonstrating) the searches for neutron oscillations, span, with the vast information that seemingly inaccessible and often neutrino mass and oscillation experi they and they alone can provide. outrageous of our theoretical specu ments at reactors, and searches for There is a good case for buying real lations.