Democracy and Political Knowledge in Ancient Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The End of Wars As the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great

Naval War College Review Volume 53 Article 3 Number 4 Autumn 2000 The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century Donald Kagan Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Kagan, Donald (2000) "The ndE of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Great Wars of the Twentieth Century," Naval War College Review: Vol. 53 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol53/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kagan: The End of Wars as the Basis for a Lasting Peace—A Look at the Gr Dr. Donald Kagan is Hillhouse Professor of History and Classics at Yale University. Professor Kagan earned a B.A. in history at Brooklyn College, an M.A. in classics from Brown University, and a Ph.D. in history from Ohio State University; he has been teaching history and classics for over forty years, at Yale since 1969. Professor Kagan has received honorary doctorates of humane let- ters from the University of New Haven and Adelphi University, as well as numerous awards and fellow- ships. He has published many books and articles, in- cluding On the Origins of War and the Preservation of Peace (1995), The Heritage of World Civilizations (1999), The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969), “Human Rights, Moralism, and Foreign Pol- icy” (1982), “World War I, World War II, World War III” (1987), “Why Western History Matters” (1994), and “Our Interest and Our Honor” (1997). -

Rebecca Futo Kennedy

Rebecca Futo Kennedy, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Classics, Women’s and Gender Studies, and Environmental Studies, Denison University Director, Denison Museum PO Box 810 Granville, OH 43023 (740) 587-8657 (office); [email protected] EDUCATION The Ohio State University; Ph.D. Greek and Latin June 2003 The Ohio State University; M.A. Greek and Latin June 1999 UC-San Diego; B.A. Classical Studies March 1997 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY • Denison University: Assistant Professor, 2009-2015; Associate Professor, 2015-present • Denison Museum: Interim Director, 2015-2016; Director, 2016-present • Union College: Visiting Assistant Professor, 2008-2009 • The George Washington University: Lecturer/Visiting Assistant Professor, 2005-2008 • Howard University: Assistant Professor, 2003-2005 PUBLICATIONS Research Interests: Political, social, and intellectual history of classical Athens; Athenian tragedy and oratory; Greek and Roman historiography; Race/ethnicity, gender, and identity formation in the ancient Mediterranean; Geography and environment in ancient Greece; Modern reception of ancient theories of human diversity (race/ethnicity); Immigration in Archaic and Classical Greece--law and history Monographs: •Immigrant Women in Athens: Gender, Ethnicity, and Citizenship in the Classical City (Routledge USA, May 2014). Reviewed in Classical Journal On-line, POLIS, Clio (in French), Journal of Hellenic Studies, Classical World, Sehepunkte, Kleio-Historia (in German). •Athena’s Justice: Athena, Athens and the Concept of Justice in Greek Tragedy, Lang Classical Series, Vol. 16 (Peter Lang, 2009). Reviews: Classical Review; Greece & Rome; L'Antiquite Classique (in French); Euphrosyne (in Portuguese); Listy filologické (in Czech). •In progress: • Book on race/ethnicity in classical antiquity and its contemporary legacy; commissioned by Johns Hopkins University Press (under contract and in progress) Edited Volumes: •Co-editor, The Routledge Handbook to Identity and the Environment in the Classical and Medieval Worlds (with Molly Jones-Lewis; Routledge UK, 2016). -

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

Politics and Policy in Corinth 421-336 B.C. Dissertation

POLITICS AND POLICY IN CORINTH 421-336 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by DONALD KAGAN, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by: Adviser Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD ................................................. 1 CHAPTER I THE LEGACY OF ARCHAIC C O R I N T H ....................7 II CORINTHIAN DIPLOMACY AFTER THE PEACE OF NICIAS . 31 III THE DECLINE OF CORINTHIAN P O W E R .................58 IV REVOLUTION AND UNION WITH ARGOS , ................ 78 V ARISTOCRACY, TYRANNY AND THE END OF CORINTHIAN INDEPENDENCE ............... 100 APPENDIXES .............................................. 135 INDEX OF PERSONAL N A M E S ................................. 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................... 145 AUTOBIOGRAPHY ........................................... 149 11 FOREWORD When one considers the important role played by Corinth in Greek affairs from the earliest times to the end of Greek freedom it is remarkable to note the paucity of monographic literature on this key city. This is particular ly true for the classical period wnere the sources are few and scattered. For the archaic period the situation has been somewhat better. One of the first attempts toward the study of Corinthian 1 history was made in 1876 by Ernst Curtius. This brief art icle had no pretensions to a thorough investigation of the subject, merely suggesting lines of inquiry and stressing the importance of numisihatic evidence. A contribution of 2 similar score was undertaken by Erich Wilisch in a brief discussion suggesting some of the problems and possible solutions. This was followed by a second brief discussion 3 by the same author. -

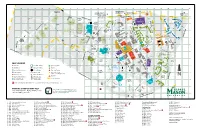

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

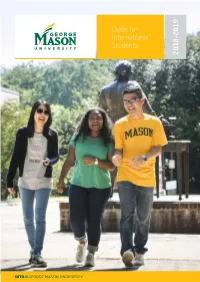

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S. -

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science FEATURE: WORTH NOTING USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library 19.1. and Archival Science portal Danielle Mihram and Curtis Fletcher publication, abstract: USC Digital Voltaire, a digital, multimodal critical edition of autograph letters, aims to combine the traditional scope of humanities inquiry with the affordancesfor and methodologies of digital scholarship, and to support scholarly inquiry at all levels, beyond the disciplines associated with Voltaire and the Enlightenment. Digital editing, and digital editions in particular, will likely expand in the next few decades as a multitude of assets become digitized and made available as online collections. One important question is: What role will librarians and archivists play in this era? USC Digital Voltaire points in one possible, creativeaccepted direction. and Voltaire’s Autograph Letters at USC edited, t the University of Southern California (USC) Special Collections Department, researchers can findcopy 31 original (autograph) letters and four poems covering the years 1742 to 1777 by Voltaire, the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, A1694–1778. Voltaire’s clear writing style, humor, and sharp intelligence made him one of the greatest writers of the French Enlightenment, a period of intellectual ferment in the late 17th and the 18th centuries. His correspondents included other leading figures of the Enlightenment,reviewed, such as the mathematician and philosopher Jean le Rond d’Alembert; Frederick II (Frederick the Great), king of Prussia; and Madame de Pompadour, the mistresspeer of King Louis XV of France. Voltaire’s voluminous correspondence currently comprisesis over 22,000 published letters, of which 16,136 are by Voltaire.1 The correspon- dence offers a multifaceted, private, and, at times, moving expression of the writer’s mss.innermost thoughts and feelings, through epistolary exchanges. -

Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 25 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 1997 1-1-1997 Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R. Grodin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph R. Grodin, Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety, 25 Hastings Const. L.Q. 1 (1997). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol25/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety By JOSEPH R. GRODIN* Most people, at least most lawyers, are aware that of the trilogy of rights made famous by the Declaration of Independence-life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness-only the first two made it into the Federal Con- stitution, felicity giving way, in the Fifth Amendment's due process clause, to a more sober concern for the rights of property.1 What most people, even most lawyers, are less likely to know is that fully two thirds of the state constitutions contain provisions which either declare the right of per- sons to pursue happiness or (along with safety) to actually "obtain" it. Scholars, as well as lawyers, have tended to ignore these state consti- tutional provisions, apparently regarding them as little more than pious echoes of the Declaration. -

Andrew J. Bacevich

ANDREW J. BACEVICH Department of International Relations Boston University 152 Bay State Road Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Telephone (617) 358-0194 email: [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Boston University Professor of History and International Relations, College of Arts & Sciences Professor, Kilachand Honors College EDUCATION Princeton University, M. A., American History, 1977; Ph.D. American Diplomatic History, 1982 United States Military Academy, West Point, B.S., 1969 FELLOWSHIPS Columbia University, George McGovern Fellow, 2014 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame Visiting Research Fellow, 2012 The American Academy in Berlin Berlin Prize Fellow, 2004 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Visiting Fellow of Strategic Studies, 1992-1993 The John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University National Security Fellow, 1987-1988 Council on Foreign Relations, New York International Affairs Fellow, 1984-1985 PREVIOUS APPOINTMENTS Boston University Director, Center for International Relations, 1998-2005 The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer; Executive Director, Foreign Policy Institute, 1993-1998 School of Arts and Sciences, Johns Hopkins University Professorial Lecturer, Department of Political Science, 1995-19 United States Military Academy, West Point Assistant Professor, Department of History, 1977-1980 1 PUBLICATIONS Books and Monographs Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country. New York: Metropolitan Books (2013); audio edition (2013). The Short American Century: A Postmortem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (2012). (editor) Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War. New York: Metropolitan Books (2010); audio edition (2010); Chinese edition (2011); Korean edition (2013). The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. -

177 Whenever I Am Called to Defend the Importance of My Job And

Book Reviews 177 Jennifer T. Roberts, (2017) The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece. New York: Oxford University Press. xxviii + 416 pages. ISBN: 9780199996643 (hbk), $34.95. Whenever I am called to defend the importance of my job and the relevance of ancient history (something I have to do all too often these days), I revert back to Thucydides, who wrote his history of the Peloponnesian War to be a ‘pos- session for all time’. According to the ‘human thing’, or kata to anthrōpinon in the Greek, Thucydides thought that the motivations and personalities – along perhaps with the events themselves – of the Peloponnesian War would hap- pen time and time again throughout human history. I think that Thucydides is more or less right, and that aside from offering a powerful and provocative lit- erary meditation on a specific conflict and set of characters, he sheds light on the human condition like few other authors have, making his work eminently applicable today. I am heartened, therefore, to find that Jennifer T. Roberts takes a similar view of Thucydides and the war he recorded. In the preface to her book, Roberts makes a passionate case for the con- tinuing relevance of the Peloponnesian War, starting with her own father’s wartime experiences and surveying the many other works – academic and popular – that have compared Thucydides’ war to the modern world. But, be- fore beginning her readable history of the Peloponnesian War geared mostly to the newcomer to that period of Greek history, Roberts argues at the outset that, invaluable as his work is, Thucydides ought now to be ‘uncoupled’ from the his- tory of the war (p. -

New and Renewing BFU Awards in 2019

League of American Bicyclists Bicycle Friendly University 2019 New and Renewing Awards Student 2019 College / University Award BFU Since City State Enrollment Status 00Platinum Platinum 0 . Colorado State University Platinum 2011 28,691 Fort Collins Colorado Renewal Portland State University Platinum 2011 27,670 Portland Oregon Renewal Stanford University Platinum 2011 20,069 Stanford California Renewal University of California, Irvine Platinum 2011 36,032 Irvine California Moved Up University of California, Santa Barbara Platinum 2011 25,145 Santa Barbara California Moved Up University of Wisconsin - Madison Platinum 2011 44,000 Madison Wisconsin Moved Up 00Gold Gold 0 . Purdue University Gold 2015 43,411 West Lafayette Indiana Moved Up The University of Arkansas Gold 2016 27,558 Fayetteville Arkansas Moved Up University of Arizona Gold 2011 45,217 Tucson Arizona Renewal University of California, Los Angeles Gold 2011 45,930 Los Angeles California Moved Up University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Gold 2013 21,570 Milwaukee Wisconsin Renewal 00Silver Silver 0 . Auburn University Silver 2015 30,440 Auburn Alabama Renewal Coastal Carolina University Silver 2015 10,641 Conway South Carolina Moved Up George Mason University, Fairfax Campus Silver 2011 30,436 Fairfax Virginia Moved Up Southern Oregon University Silver 2016 4,268 Ashland Oregon Renewal The Ohio State University Silver 2011 61,170 Columbus Ohio Moved Up University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Silver 2011 43,649 Urbana Illinois Moved Up University of Massachusetts Lowell Silver 2015 18,257 Lowell Massachusetts Moved Up University of Michigan Ann Arbor Silver 2012 46,002 Ann Arbor Michigan Renewal Virginia Tech Silver 2013 34,850 Blacksburg Virginia Moved Up 00Bronze Bronze 0 . -

Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government

Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government Tyler Cowen Tyler Cowen. “Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government.” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, 2000. ABSTRACT The 20th century has seen some of the greatest restrictions on liberty of any period in human history, as well as significant liberalizations and improvements. These questions do not always hold a central place in mainstream academic dis- course, but there are scholars who seek to explain how and why these changes have occurred. This paper attempts to make this research accessible to a broader audience. It presents relevant research on social change and concludes that Western societies are not headed off the proverbial economic cliff. Even though governments may be larger and more bureaucratic than before, they largely con- tinue to support freedom because failure to do so could destroy the entire system. Moreover, market-oriented economies have demonstrated a lasting ability to out- compete alternatives, such as communism. Technological changes and advance- ments hold a promise for greater freedom and prosperity across the world. JEL codes: B25, B59, D72, H10, H60, K10, L51, 057, P11, P16, Q58 Keywords: classical liberalism, constitution, corporations, deregulation, economic development, environmental regulation, free market, globalization, liberty, mass media, New Zealand miracle, public choice, rational irrationality, social change, Thatcher revolution, Tullock paradox, Westminster system AUTHOR’S NOTE Mercatus first put this piece out in 2000. We all thought it was worthwhile to revisit these issues, given the uncertain course of liberty in today’s world.