Indiana Law Review Volume 48 2015 Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedy Taken Seriously the Mafia’S Ties to a Murder

MONDAY Beauty and the Beast www.annistonstar.com/tv The series returns with an all-new episode that finds Vincent (Jay Ryan) being TVstar arrested for May 30 - June 5, 2014 murder. 8 p.m. on The CW TUESDAY Celebrity Wife Swap Rock prince Dweezil Zappa trades his mate for the spouse of a former MLB outfielder. 9 p.m. on ABC THURSDAY Elementary Watson (Lucy Liu) and Holmes launch an investigation into Comedy Taken Seriously the mafia’s ties to a murder. J.B. Smoove is the dynamic new host of NBC’s 9:01 p.m. on CBS standup comedy competition “Last Comic Standing,” airing Mondays at 7 p.m. Get the deal of a lifetime for Home Phone Service. * $ Cable ONE is #1 in customer satisfaction for home phone.* /mo Talk about value! $25 a month for life for Cable ONE Phone. Now you’ve got unlimited local calling and FREE 25 long distance in the continental U.S. All with no contract and a 30-Day Money-Back Guarantee. It’s the best FOR LIFE deal on the most reliable phone service. $25 a month for life. Don’t wait! 1-855-CABLE-ONE cableone.net *Limited Time Offer. Promotional rate quoted good for eligible residential New Customers. Existing customers may lose current discounts by subscribing to this offer. Changes to customer’s pre-existing services initiated by customer during the promotional period may void Phone offer discount. Offer cannot be combined with any other discounts or promotions and excludes taxes, fees and any equipment charges. -

Fire Chief Requests Layoff, Resigns REQUEST: Jim Walkowski Is Also the Acting Chief of the Tached to Any Existing Job Offer Mead

Warriors Edge Beavers Rochester Tops Evergreen Division Rival Tenino 5-4 / Sports 1 Fallen Logger Remembered / Main 3 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com April 3, 2014 Fire Chief Requests Layoff, Resigns REQUEST: Jim Walkowski is also the acting chief of the tached to any existing job offer Mead. His start date is May 1, sion. Chehalis Fire Department, on or opportunity elsewhere. according to the Facebook post. The Chronicle has requested Says Request Aimed at Wednesday asked the RFA Gov- Hours later, Spokane Fire By 11 p.m., Walkowski sub- a copy of Walkowski’s contract Improving Agency Finances ernance Board to lay him off as District 9 announced via its mitted a letter of resignation to with RFA. It’s unclear what com- a way to improve the financial Facebook page that the eight- the RFA board. pensation Walkowski would By Kyle Spurr condition of the agency. year member of the fire authori- During its meeting, the have been entitled to should he [email protected] When asked about his mo- ty had accepted a job as assistant board had tabled the request, have been removed as chief be- fore the contract’s completion. Riverside Fire Author- tivation for such a request, he chief for the Eastern Washing- choosing to collect more infor- ity Chief Jim Walkowski, who insisted it wasn’t necessarily at- ton fire department based in mation before making a deci- please see CHIEF, page Main 10 Ballots Age, Finances Spell End for 79-Year-Old Fraternity for Veterans Going Out for Tenino Last Roll Call at the Bond Election Toledo VFW Hall SECOND TIME AROUND: Bond Proponents Hoping for Supermarjority on $38 Million Measure By Christopher Brewer [email protected] Voters in the Tenino School District are beginning to re- ceive ballots asking them to once again vote on a $38 mil- lion bond. -

Human Factors Industry News ! Volume XV

Aviation Human Factors Industry News ! Volume XV. Issue 02, January 20, 2019 Hello all, To subscribe send an email to: [email protected] In this weeks edition of Aviation Human Factors Industry News you will read the following stories: ★37 years ago: The horror and ★Florida man decapitated in freak heroism of Air Florida Flight 90 helicopter accident identified, authorities say ★Crash: Saha B703 at Fath on Jan at14th Bedford 2019, landed a few atyears wrong ago airport was a perfect★Mechanic's example of error professionals blamed for 2017 who had drifted over years into a very unsafeGerman operation. helicopter This crash crew in Mali ★ACCIDENT CASE STUDY BLIND wasOVER literally BAKERSFIELD an “accident waiting to happen”★11 Aviation and never Quotes through That Coulda conscious decision. This very same processSave fooledYour Life a very smart bunch of★Aviation engineers Safety and managersNetwork at NASA and brought down two US space shuttles!Publishes This 2018 process Accident is builtStatistics into our human★Australian software. Safety Authority Seeks Proposal On Fatigue Rules ★ACCIDENT CASE STUDY BLIND OVER BAKERSFIELD Human Factors Industry News 1 37 years ago: The horror and heroism of Air Florida Flight 90 A U.S. Park Police helicopter pulls two people from the wreckage of an Air Florida jetliner that crashed into the Potomac River when it hit a bridge after taking off from National Airport in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 13, 1982. On last Sunday, the nation's capital was pummeled with up to 8 inches of snow, the first significant winter storm in Washington in more than three years. -

NCA Spectra March 2020

The Magazine of the National Communication Association March 2020 | Volume 56, Number 1 HOW COMMUNICATION SHAPES THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN NCA_Spectra_2020_March_FINAL.indd 1 2/18/20 3:26 PM ABOUT Spectra, the magazine of the National Communication Association 2019 NCA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (NCA), features articles on topics that are relevant to Communication President scholars, teachers, and practitioners. Spectra is one means through which NCA works toward accomplishing its mission of advancing Kent Ono, University of Utah Communication as the discipline that studies all forms, modes, media, First Vice President and consequences of communication through humanistic, social David T. McMahan, Missouri Western State University scientific, and aesthetic inquiry. Second Vice President NCA serves its members by enabling and supporting their professional Roseann Mandziuk, Texas State University interests. Dedicated to fostering and promoting free and ethical communication, NCA promotes the widespread appreciation of the Immediate Past President importance of communication in public and private life, the Star Muir, George Mason University application of competent communication to improve the quality of human life and relationships, and the use of knowledge about Diversity Council Chair communication to solve human problems. NCA supports inclusiveness Rachel Alicia Griffin, University of Utah and diversity among our faculties, within our membership, in the Publications Council Chair workplace, and in the classroom; NCA supports and promotes policies Kevin Barge, Texas A&M University that fairly encourage this diversity and inclusion. Research Council Chair The views and opinions expressed in Spectra articles are those of the Charles Morris III, Syracuse University authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Communication Association. -

Programming Notes - First Read

Programming notes - First Read Hotmail More TODAY Nightly News Rock Center Meet the Press Dateline msnbc Breaking News EveryBlock Newsvine Account ▾ Home US World Politics Business Sports Entertainment Health Tech & science Travel Local Weather Advertise | AdChoices Recommended: Recommended: Recommended: 3 Recommended: First Thoughts: My, VIDEO: The Week remaining First Thoughts: How New iPads are Selling my, Myanmar That Was: Gifts, undecided House Rebuilding time for Under $40 fiscal cliff, and races verbal fisticuffs How Cruise Lines Fill All Those Unsold Cruise Cabins What Happens When You Take a Testosterone The first place for news and analysis from the NBC News Political Unit. Follow us on Supplement Twitter. ↓ About this blog ↓ Archives E-mail updates Follow on Twitter Subscribe to RSS Like 34k 1 comment Recommend 3 0 older3 Programming notes newer days ago *** Friday's "The Daily Rundown" line-up with guest host Luke Russert: NBC's Kelly O'Donnell on Petraeus' testimony… NBC's Ayman Mohyeldin live in Gaza… one of us (!!!) with more on the Republican reaction to Romney… NBC's Mike Viqueira on today's White House meeting on the fiscal cliff and The Economist's Greg Ip and National Journal's Jim Tankersley on the "what ifs" surrounding the cliff… New NRCC Chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) on the House GOP's road forward… Democratic strategist Doug Thornell, Roll Call's David Drucker and the New York Times' Jackie Calmes on how the next round of negotiations could be different (or all too similar) to the last time. Advertise | AdChoices *** Friday’s “Jansing & How to Improve Memory E-Cigarettes Exposed: Stony Brook Co.” line-up: MSNBC’s Chris with Scientifically Designed The E-Cigarette craze is sweeping the country. -

211 Potential Witnesses in Riffe Trial

Midweek Edition Thursday, Discovery Tours Aug. 22, 2013 Update $1 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com / Main 9 Modern Day Hero Twin Cities 15s Finish 1-3 High School-Aged Group Rocks Local Local Team Loses to Rhode Island, Heading Events, Venues / Life 1 Home from the East Coast / Sports 1 211 Potential Witnesses in Riffe Trial 1985 MURDER Trial for Prosecutors filed a list of Edward “Ed” Maurin, 81, both More than 30 of the people Prosecutor Will more than 200 people who may of Ethel, in 1985. on the list live in seven differ- Halstead, who Man Accused of Double- testify in a cold case murder His trial, which is anticipat- ent states — including Arizona, is handling the Homicide Set to Begin trial set to occur this October in ed to last between four and six Alaska, Oklahoma, Oregon, case. He said Rick Riffe Lewis County Superior Court. weeks, is set to start Oct. 7. California, Texas and Ohio — prosecutors do in October Rick Riffe is charged with The prosecution’s witness and if they are called to testify, not know yet how much the trial By Stephanie Schendel murder, kidnapping and rob- list, which is 29 pages long, fea- the cost of their travel and hous- will cost. bery for the deaths of Wilhelmi- tured the names of 211 people ing will come out of the prosecu- [email protected] na “Minnie” Maurin, 83, and from throughout the country. tor’s office budget, said Deputy please see TRIAL, page Main 14 Final Stage of I-5 Widening The Bird is Back Project Iconic Yard Birds Fowl Ready for Saturday’s Celebration Underway CONSTRUCTION Traffic Impacts to Begin Monday with Nighttime Lane Closures By Kyle Spurr [email protected] The final stage of the In- terstate 5, Mellen Street to Blakeslee Junction project in Centralia will begin to impact drivers Monday night with nighttime lane closures, traffic shifts and roadside work. -

The Politics of Fashion: American Leaders and Image Perception

THE POLITICS OF FASHION: AMERICAN LEADERS AND IMAGE PERCEPTION A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Science of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture & Technology By Joanna S. Rosholm, B.A. Washington, D.C. April 30, 2009 THE POLITICS OF FASHION: AMERICAN LEADERS AND IMAGE PERCEPTION Joanna S. Rosholm, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Diana M. Owen, Ph. D. Abstract Physical appearance is an important non-verbal communicator for public officials, as they are often in the public eye. As a result, oneʼs fashion and style can affect oneʼs political viability. All politicians are expected to dress in a certain way, a style that former Democratic National Committee Communications Director, Karen Finney, believes “conveys a degree of thoughtfulness and seriousness,” (Personal Interview, 2009). These expectations are merely guidelines to attire that demonstrates the correct balance between masculinity and femininity, between paying attention to detail while appearing effortless, and maintaining oneʼs personal character. Case studies, personal experience, and personal interviews with Karen Finney, Anita Dunn, Peter Kovar, Tim Gunn, and Rochelle Behrens illustrate the importance of what public officials wear. Secretary Hillary Clinton, Governor Sarah Palin, Congressman Barney Frank and Congresswoman Loretta Sanchez are used as examples to demonstrate key points. Among the key findings, it is found that female candidates on the campaign trail continue to struggle with social permission to don casual attire. As well, while it is important to maintain a “gender appropriate” image, Hillary Clinton ii | P a g e demonstrates how women often perform their political roles through their clothing. -

Jesse Ferguson RE: Benenson's Cocktails on 4.10.15

EVENT MEMO FR: Jesse Ferguson RE: Benenson’s Cocktails on 4.10.15 This is an off-the-record cocktails with the key national reporters, especially (though not exclusively) those that are based in New York. Much of the group includes influential reporters, anchors and editors. The goals of the dinner include: (1) Give reporters their first thoughts from team HRC in advance of the announcement (2) Setting expectations for the announcement and launch period (3) Framing the HRC message and framing the race (4) Enjoy a Frida night drink before working more TIME/DATE: As a reminder, this is called for 6:30 p.m. on Friday, April 10th. There are several attendees – including Diane Sawyer – who will be there promptly at 6:30 p.m. but have to leave by 7 p.m. LOCATION: The address of his home is 60 E. 96th Street, #12B, New York, 10128. CONTACT: If you have last minute emergencies please contact me (703-966-2689) or Joel Benenson (917-991-0155). FOOD: This will include cocktails and passed hours devours. REPORTER RSVPs YES 1. ABC - Cecilia Vega 2. ABC - David Muir 3. ABC – Diane Sawyer 4. ABC – George Stephanoplous 5. ABC - Jon Karl 6. Bloomberg – John Heillman 7. Bloomberg – Mark Halperin 8. CBS - Norah O'Donnell 9. CBS - Vicki Gordon 10. CNN - Brianna Keilar 11. CNN - David Chalian 12. CNN – Gloria Borger 13. CNN - Jeff Zeleny 14. CNN – John Berman 15. CNN – Kate Bouldan 16. CNN - Mark Preston 17. CNN - Sam Feist 18. Daily Beast - Jackie Kucinich 19. GPG - Mike Feldman 20. -

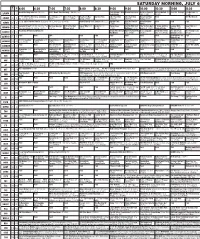

Saturday Morning, July 6

SATURDAY MORNING, JULY 6 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sat (N) (cc) Jack Hanna’s Wild Ocean Mysteries Born to Explore Recipe Rehab (N) Food for Thought Sea Rescue (N) 2/KATU 2 2 Countdown (N) (TVG) (TVG) (TVG) 5:00 CBS This Morning: Saturday Doodlebops (cc) Doodlebops Fair Busytown Mys- Garden Time Liberty’s Kids Liberty’s Kids Busytown Mys- Paid Go! Northwest 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) (Cont’d) (TVY) Share. (TVY) teries (TVY) (TVY7) (TVY7) teries (TVY) 5:00 2013 Tour de France Stage 8. (N) (Live) (cc) (Cont’d) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) Justin Time Tree Fu Tom (N) Animal Adven- Paid Paid Paid 8/KGW 8 8 (TVY) (TVY) tures Sesame Street Lifting Snuffy. Zoe Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) SciGirls (cc) Cyberchase Fetch! With Ruff The Victory Gar- P. Allen Smith’s Sewing With Sew It All (cc) 10/KOPB 10 10 choreographs a dance. (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVG) (TVY) Ruffman (TVY) den Hot. (TVG) Garden Home Nancy (TVG) (TVG) Good Day Oregon Saturday (N) Elizabeth’s Great Mystery Hunters Eco Company (cc) Teen Kids News The American The Young Icons 12/KPTV 12 12 Big World (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (N) (cc) (TVG) Athlete (TVG) (TVG) Paid Paid TBA Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Atmosphere for Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Miracles w/ 3-2-1 Penguins! VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) 3-2-1 Penguins! VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) VeggieTales (cc) 3-2-1 Penguins! 24/KNMT 20 20 (cc) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (cc) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) (cc) (TVY) Paid Paid Rescue Heroes Adventures of Sonic X A Wild Sonic X Map of Justice League Justice League Dragon Ball Z Kai Dragon Ball Z Kai Yu-Gi-Oh! (cc) Yu-Gi-Oh! ZEXAL 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVY) Nanoboy Win. -

CRM / SA…You’Re Not Bourne with It LESSON OBJECTIVE

EMT Refresher 2018 James Temple CRM / SA…You’re Not Bourne With It LESSON OBJECTIVE ▪ • Define Crew Resource Management (CRM) ▪ • Explain the benefits of CRM to EMS ▪ • State the guiding principles of CRM and briefly explain each ▪ • Explain the concept of communication in the team environment using advocacy/inquiry or appreciative inquiry ▪ • State characteristics of effective team leaders ▪ • State characteristics of effective team members ▪ • Explain how the use of CRM can reduce errors in patient care IOM 1999 “To Err is Human” ▪ “People make fewer errors when they work in teams. When processes are planned and standardized, each member knows his or her responsibilities as well as those of teammates, and members “look out” for one another, noticing errors before they cause an accident.” Why Aviation? ▪ Commonalities between aviation and healthcare – High risk environment – Highly skilled professionals – Failures in teamwork can have deadly effects ▪ What aviation has learned… – Most crashes involve teamwork failure rather than mechanical failure – Accident rate reduced since the introduction of CRM Are you Chuck Norris? The Error Chain ▪ A series of event links that, when considered together, cause a mishap ▪ Should any one of the links be “broken,” then the mishap probably will not occur ▪ It is up to each crewmember to recognize a link and break the error chain Aeroflot Flight 593 ▪ Airbus A310-300 ▪ Moscow – Hong Kong ▪ March, 1994 ▪ Pilot allowed his kids (12 and 16) to sit and “control” the plane (1) – Autopilot engaged, no real control of plane – Older boy actually disengaged auto pilot with pressure on the stick – No one realized this disconnect ▪ Non-audible warning light (pilots not familiar with this particular plane) ▪ The aircraft rolled into a steep bank and near-vertical dive. -

Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications USF Faculty Publications 2019 Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001 David Shedden [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fac_publications Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shedden, D. (2019). Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001. Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the USF Faculty Publications at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. __________________________________________ Florida Newspaper History Chronology 1783-2001 The East-Florida Gazette, Courtesy Florida Memory Program By David Shedden Updated September 17, 2019 __________________________________________ CONTENTS • INTRODUCTION • CHRONOLOGY (1783-2001) • APPENDIXES Daily Newspapers -- General Distribution Weekly Newspapers and other Non-Dailies -- General Distribution African-American Newspapers College Newspapers Pulitzer Prize Winners -- Florida Newspapers Related Resources • BIBLIOGRAPHY 2 INTRODUCTION Our chronology looks at the history of Florida newspapers. It begins in 1783 during the last days of British rule and ends with the first generation of news websites. Old yellowed newspapers, rolls of microfilm, and archived web pages not only preserve stories about the history of Florida and the world, but they also give us insight into the people who have worked for the state’s newspapers. This chronology only scratches the surface of a very long and complex story, but hopefully it will serve as a useful reference tool for researchers and journalism historians. -

Exploring the Future of Politics

July 2015 IOP Seniors • On the Record • Politics of Race and Ethnicity • Campaigns and Advocacy Program • Careers and Internships • Policy Groups • Spring Resident Fellows • JFK Jr. Forum • Spring Photo Collections • New Millennials Poll • Women’s Initiative in Leadership #IOPSummer15 • Professional Updates from IOP Alumni EXPLORING THE FUTURE OF POLITICS From justice and equality to principles of democracy, visionary thought leaders captivated spring audiences at the Institute with their bold prescriptions for effecting positive change in the world. Speakers advocated many paths to progress, emphasizing technology, education and the need for an engaged citizenry. IOP Seniors CONGRATULATIONS GRADUATING IOP SENIORS (Row 1): IOP Director Maggie Williams and graduating senior Daniel Ki ’15 at the May 27 IOP Senior Brunch event; (Row 2): IOP seniors Sietse Goffard and Eva Guidarini; Sylvia Percovich, Leah Goldman, Hannah Phillips, Eva Guidarini, Valentina Perez and Holly Flynn. On May 27, the IOP was proud to host nearly two dozen Harvard graduating Seniors and their families for brunch to celebrate their graduation from Harvard – and their incredible work helping the IOP achieve its mission. More information about our Seniors and their next moves after Harvard can be found in the “IOP on the Move” section on pages 17–18. Congrats, Seniors! COVER PHOTOS: (Row 1): Brandon Stanton, founder of Humans of New York, greets students and guests during his Feb. 11 JFK Jr. Forum lecture; founder of The Equal Justice Initiative Bryan Stevenson discusses the criminal justice system on April 2; (Row 2): Spring 2015 Fellows gather for a panel discussion during the IOP’s “Open House” event on Feb.