Wicked Game of Smart Specialization : a Player's Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Denver, CO May 14Th - May 16Th 2021

Denver, CO May 14th - May 16th 2021 Elite 8 Junior Dancer Shylee Sagle - Must See - Summit Dance Academy 1st Runner-Up - Brielle Incorvaia - Meeting In The Ladies Room - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy 2nd Runner-Up - Tenlee Tope - Small World - Summit Dance Academy Elite 8 Teen Dancer Cara Carr - Roxie - Dance Unlimited - Colorado 1st Runner-Up - Ryla Maestas - Transformative - Roots Studios 2nd Runner-Up - Keira Claar - Take On Me - Studio 9 Dance Academy Elite 8 Senior Dancer Tyler Airozo - Silver Screen - Roots Studios 1st Runner-Up - Makenna Nemec - Man In The Mirror - X-treme Dance Force 2nd Runner-Up - Mary Davis - My Perogative - Roots Studios Top Select Petite Solo 1 - Vienne Paradis - Love Will Keep Us Together - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy 2 - Avery Schuetz - 20th Century Fox - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Shylee Sagle - Must See - Summit Dance Academy 2 - Carsyn Henry - Variations L-lv - Studio 9 Dance Academy 3 - Hadlee Wolf - Home - Studio 9 Dance Academy 4 - Emily Benjamin - Roxie - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy 5 - Ella Miller - For Now I Am Winter - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy 6 - Ava Space - Love You I Do - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy 7 - Sophia Rice - The Face - Dance Unlimited - Colorado 8 - Tenlee Tope - Small World - Summit Dance Academy 9 - Courtney Lande - I Think It's Going To Rain Today - Dance Unlimited - Colorado 10 - Evelin Yannett - Feelin Good - DanceSpace Performing Arts Academy Top Select Teen Solo 1 - Kate Smith - We Call - Studio 9 Dance Academy -

May 29Th 2021

Published Bi-Weekly for the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska • Volume 50, Number 11 • Saturday, May 29, 2021 Bago Bits… Winnebago Football Earns Trip to the Championship Game Winnebago Comprehensive Healthcare System CEO Danelle Smith pictured after the Majestry Swear-In Ceremony con- ducted by Winnebago Tribal Chairwoman Victoria Kitcheyan on May 11th in the Tribal Chambers. Winnebago, NE – The Winnebago the win. Nation (4) not allowing them to score. High School Football team fi nd them- After the win, Winnebago was seeded After the game, Tiospa Zina called out selves facing a familiar foe for this year’s #2 in the playoffs. That put Winnebago Winnebago in the live stream and got championship game. The #1 ranked and the #3 ranked Lower Brule Sioux their wish. This game is for the All- Congratulations to the Winnebago Public Tiospa Zina will go head-to-head with on a collision course to battle it out in Nations Championship title. Winnebago School’s One Act Play on their amaz- Winnebago in the All-Nations Football the semi-final game. This game was is playing for the fi rst time in the league ing performances during both May 11th League Championship game. Tiospa played on Friday, May 21 in Mitchell, and earned 5 victories. “It’s hard to beat and May 12th shows. Thank you to Mrs. Spirk and the students for all the hard Zina gave Winnebago their only loss back South Dakota at the Joe Quintal Football a team twice if Winnebago wants it, they work and dedication! in the beginning of May. -

Chad Wilson Bailey Song List

Chad Wilson Bailey Song List ACDC • Shook me all night long • It’s a long way to the top • Highway to hell • Have a drink on me Alanis Morissette • One Hand in my Pocket Alice in Chains • Heaven beside you • Don’t follow • Rooster • Down in a hole • Nutshell • Man in the box • No excuses Alison Krauss • When you say nothing at all America • Horse with no name Arc Angels • Living in a dream Atlantic Rhythm Section • Spooky Audioslave • Be yourself • Like a stone • I am the highway Avicii • Wake me up Bad Company • Feel like makin’ love • Shooting star Ben E King • Stand by me Ben Harper • Excuse me • Steal my kisses • Burn one down Better than Ezra • Good Billie Joel • You may be right Blues Traveler • But anyway Bob Dylan • Tangled up in blue • Subterranean homesick blues • Shelter from the storm • Lay lady Lay • Like a rolling stone • Don’t think twice Bob Marley • Exodus • Three little birds • Stir it up • No woman, no cry Bob Seger • Turn the page • Old time rock and roll • Against the wind • Night moves Bon Iver • Skinny love • Holocene Bon Jovi • Dead or Alive Bruce Hornsby • Mandolin Rain • That’s just the way it is Bruce Springstein • Hungry heart • Your hometown • Secret garden • Glory days • Brilliant disguise • Terry’s song • I’m on fire • Atlantic city • Dancing in the dark • Radio nowhere Bryan Adams • Summer of ‘69 • Run to you • Cuts like a knife Buffalo Springfield • For what its worth Canned Heat • Going up to country Cat Stevens • Mad world • Wild world • The wind CCR • Bad moon rising • Heard it through the grapevine • Run through the jungle • Have you ever seen the rain • Suzie Q Cheap Trick • Surrender Chris Cornell • Nothing compares to you • Seasons Chris Isaak • Wicked Games Chris Stapleton • Tennessee Whiskey Christopher Cross • Ride like the wind Citizen Cope • Sun’s gonna rise Coldplay • O (Flock of birds) • Clocks • Yellow • Paradise • Green eyes • Sparks Colin Hay • I don’t think I’ll ever get over you • Waiting for my real life to begin Counting Crows • Around here • A long December • Mr. -

Wicked Games”

“WICKED GAMES” By KATRINA WOOD [email protected] FADE IN: FUNERAL SETTING: FUNERAL INT of Church MORNING- SUMMER The Mays family sits in the front pew of a small white church; stain glass windows let the warmth of the summer heat circulate. Nine- year-old Lily stands in the front and stares into her grandmother's coffin. She tries to hide her tears, veiling herself with her black hair. LILY Whispers Don't leave me here with these evil people grandma. She turns slowly to see the cold stare of her mother (DOROTHY and brother DUKE. She rubs a red mark on the back of her neck that resembles a wine stain. Two-Years Later THE OPENING CREDITS Sign swings ‘Welcome to Sweetwater’. 2 We move over the roads that twist sporadically through the dense woods and farmlands. Farmhouses sit in the back with great distances between. A feel of dread linger as you move along the trail in woods up to an old white Victorian house. 11 year-old LILY MAYS finds $10 on her way home from school. Excited she buys a doll from the store. INT HOUSE. KITCHEN. EVENING – FALL DOROTHY TALKS TO LILY IN THE KITCHEN WHILE SHE COOKS. DOROTHY Girl you know that money you spent is tainted. Dorothy watches for her reaction. However, Lily smiles at her doll, unfazed by her mother. Dorothy slams her hand on the table. DOROTHY Do you hear me?” Lily calmly looks up. LILY (softly) 3 No, it’s not mama, the money was lying on the side of the road. -

Showbiz Lakeland 2021 Overalls

Showbiz Lakeland 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio Sapphire Minis Solo 1 Over The Rainbow Olivia Kapron JMB Dance Academy 2 Sugar Pie Honey Bunch Violet Mcdade The Dance Company Sapphire Petite Solo 1 Supercalifragilistic Kayla Walker JMB Dance Academy 2 Neglected Garden Arabella Tucker LA Dance Center LLC Sapphire Petite Duet/Trio 1 One And The Same University Performing Arts Centre Sapphire Petite Small Group 1 Face To Face LA Dance Center LLC 2 He Mele No Lilo LA Dance Center LLC Sapphire Petite Large Group 1 Teach Me How To Shimmy University Performing Arts Centre 2 Shop Around University Performing Arts Centre Sapphire Pre-Junior Solo 1 Swag Aiselyn Steward JMB Dance Academy 2 It's All About Me Kylie Kimmel Independent- Kimmel Sapphire Junior Solo 1 You Must Not Know My Name Genesis Carter Boundless Dance Company Sapphire Junior Duet/Trio 1 Dem Beats JMB Dance Academy Sapphire Junior Small Group 1 Carry You Expressions Academy of Dance 2 Wherever You Will Go Expressions Academy of Dance Sapphire Pre-Teen Solo 1 The Alto's Lament Naia Colbert Boundless Dance Company Sapphire Teen Solo 1 Before You Go Amara Furniss Boundless Dance Company 2 Doll House Sophia Lockwood Boundless Dance Company Sapphire Teen Large Group 1 All About the Money Citrus Academy Of Dance And Arts Showbiz Lakeland 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio 2 Do It Like This Citrus Academy Of Dance And Arts Ruby Petite Solo 1 Not About Angels Adalyn Torres Your Haven Dance Company 2 Dynasty Emma Wagner Your Haven Dance Company Ruby Petite Duet/Trio 1 Bathing -

Revealed – the Ultimate Foreplaylist (According to Spotify)

Revealed – The Ultimate Foreplaylist (According to Spotify) - The Weeknd is the world’s most listened-to artist on Spotify during sex – - “Neighbors Know My Name” by Trey Songz is the go-to track – If you’re wanting to spice things up in the bedroom with a sensual playlist but are unsure of what to put on, new data analysis by pelvic healthcare company Kegel8 reveals the world’s most listened-to tracks during sex. By analysing different sex-themed playlists on the music streaming service Spotify – using the search terms “Sex”, “Netflix and Chill”, “Date Night”, “Make Love”, “Baby Making” – Kegel8 has uncovered the most popular tracks and artists for getting hot and steamy among world-wide listeners: “Neighbors Know My Name” by American singer, songwriter and rapper Trey Songz features in the most sex-themed playlists, despite being released a decade ago, closely followed by a second song by the artist “Slow Motion” released in 2015. The Grammy Award winning “Earned It” by Canadian singer and songwriter The Weeknd comes in fourth, made famous as the lead single from the Fifty Shades of Grey soundtrack – a film known for its erotic scenes. Kegel8 also identified the most listened-to artists in sex-themed playlists. The Weeknd, Trey Songz, Jeremih, Ed Sheeran and Ginuwine are the top 5 most listened-to artists during sex, with each featuring in over 1000 playlists. When it comes to getting couples in the mood, these artists have it covered: It also seems there’s a perfect length, tempo, key and era too. Who knew!? The average song listened to during sex is just under 4 minutes (make of that what you will!), it’s released in the 2010s, is sung in the key “G” and has a moderate tempo of 115 beats per minute. -

Orientation Trims A

Volume 148, Issue 39 www.sjsunews.com/spartan_daily Wednesday, May 3, 2017 SPARTAN DAILY SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 GONG CHA COMES TO DOWNTOWN SJ LATE MOTHER MOTIVATES PITCHER See review on page 3 See profi le on page 8 #spartanpolls Is a suicide-prevention net necessary for the Golden @spartandaily Gate Bridge? FOLLOW US! @SpartanDaily @spartandaily/spartandaily /spartandailyYT INCOMING SPARTANS Orientation STARBOY: LEGEND OF THE FALL trims a day BY JENNIFER BALLARDO Staff Writer San Jose State is making some changes to the freshman orientation schedule this coming summer. The biggest change being made is the switch from a two-day program to a one-day event. Gregory Wolcott, Director of New Student and Family Programs at SJSU, believes that this change will bring varied feedback. New Student and Family Programs is an organization that helps new students and their families transition into SJSU. “I think it’ll be a little bit of a mixed response,” Wolcott said. “For some it was great, I think some students loved staying on campus and I think for some students that added stress to the program.” Incoming psychology freshman Karina Zesati is frustrated about the change. “In my opinion staying overnight would have been a good experience for the people that won’t be in housing and for people who want to get a feel of what it’s going to be like,” Zesati said. JASON REED | CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER There is a “summer frosh orientation fee,” which The Weeknd stopped by San Jose to perform as a part of his world tour “Starboy: Legend of the Fall” at the SAP covers programming costs, parking and meals. -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Artist Song Title Disc # Artist Song Title Disc # (children's Songs) I've Been Working On The 04786 (christmas) Pointer Santa Claus Is Coming To 08087 Railroad Sisters, The Town London Bridge Is Falling 05793 (christmas) Presley, Blue Christmas 01032 Down Elvis Mary Had A Little Lamb 06220 (christmas) Reggae Man O Christmas Tree (o 11928 Polly Wolly Doodle 07454 Tannenbaum) (christmas) Sia Everyday Is Christmas 11784 She'll Be Comin' Round The 08344 Mountain (christmas) Strait, Christmas Cookies 11754 Skip To My Lou 08545 George (duet) 50 Cent & Nate 21 Questions 00036 This Old Man 09599 Dogg Three Blind Mice 09631 (duet) Adams, Bryan & When You're Gone 10534 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 09938 Melanie C. (christian) Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 09228 (duet) Adams, Bryan & All For Love 00228 (christmas) Deck The Halls 02052 Sting & Rod Stewart (duet) Alex & Sierra Scarecrow 08155 Greensleeves 03464 (duet) All Star Tribute What's Goin' On 10428 I Saw Mommy Kissing 04438 Santa Claus (duet) Anka, Paul & Pennies From Heaven 07334 Jingle Bells 05154 Michael Buble (duet) Aqua Barbie Girl 00727 Joy To The World 05169 (duet) Atlantic Starr Always 00342 Little Drummer Boy 05711 I'll Remember You 04667 Rudolph The Red-nosed 07990 Reindeer Secret Lovers 08191 Santa Claus Is Coming To 08088 (duet) Balvin, J. & Safari 08057 Town Pharrell Williams & Bia Sleigh Ride 08564 & Sky Twelve Days Of Christmas, 09934 (duet) Barenaked Ladies If I Had $1,000,000 04597 The (duet) Base, Rob & D.j. It Takes Two 05028 We Wish You A Merry 10324 E-z Rock Christmas (duet) Beyonce & Freedom 03007 (christmas) (duets) Year Snow Miser Song 11989 Kendrick Lamar Without A Santa Claus (duet) Beyonce & Luther Closer I Get To You, The 01633 (christmas) (musical) We Need A Little Christmas 10314 Vandross Mame (duet) Black, Clint & Bad Goodbye, A 00674 (christmas) Andrew Christmas Island 11755 Wynonna Sisters, The (duet) Blige, Mary J. -

TOP AFP/AUDIOGEST Semanas 01 a 26 De 2020

TOP AFP/AUDIOGEST Semanas 01 a 26 de 2020 De 27/12/2019 a 25/06/2020 CONTEÚDO DO RELATÓRIO > Top 100 Álbuns (TOP 100 A) > Top 50 Compilações (TOP 50 C) > Top 3000 Streaming > Top 3000 Singles + EPs Digitais Top 100 Álbuns Semanas 01 a 26 de 2020 Índice De 27/12/2019 a 25/06/2020 Posição Gal. Titulo Artista Etiqueta Editora Físico Editora Digital 1 MAP OF SOUL: 7 BTS BIG HIT ENTERTAINMENT NUBA RECORDS THE ORCHARD 2 FINE LINE HARRY STYLES COLUMBIA SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 3 40 ANOS A DAR NO DURO XUTOS & PONTAPÉS UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 4 PL WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO? BILLIE EILISH INTERSCOPE UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 5 O MÉTODO RODRIGO LEÃO BMG WARNER WARNER 6 YELLOW CALEMA KLASSZIK SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 7 THE SLOW RUSH TAME IMPALA CAROLINE UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 8 AQUI ESTÁ-SE SOSSEGADO CAMANÉ & MÁRIO LAGINHA PARLOPHONE WARNER WARNER 9 GIGATON PEARL JAM REPUBLIC RECORDS UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 10 THANKS FOR THE DANCE LEONARD COHEN COLUMBIA / LEGACY SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 11 ZECA PEDRO JÓIA SONY SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 12 9 ELAS SONY MUSIC/RUELA MUSIC/DRAGON MUSIC-EVC SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 13 OITENTA CARLOS DO CARMO UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 14 EVERYDAY LIFE COLDPLAY PARLOPHONE WARNER WARNER 15 MADREPÉROLA CAPICUA UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 16 CHROMATICA LADY GAGA INTERSCOPE UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 17 ABBEY ROAD THE BEATLES BEATLES UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 18 GHOSTEEN NICK CAVE AND THE BAD SEEDS KOBALT POPSTOCK POPSTOCK 19 BEST OF DULCE PONTES UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 20 PL AS CANÇÕES DAS NOSSAS VIDAS - ACÚSTICO - 30 ANOS TONY CARREIRA REGI-CONCERTO SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 21 THE PLATINUM COLLECTION QUEEN ISLAND UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 22 SOUTH SIDE BOY DIOGO PIÇARRA UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 23 BRINCA E APRENDE COM O PANDA E OS CARICAS PANDA E OS CARICAS UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 24 OU MAIS ANTIGO BISPO SONY SONY MUSIC SONY MUSIC 25 CHANGES JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL 26 ERA UMA VEZ.. -

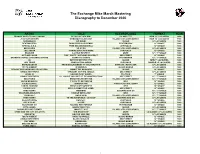

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Die for You Free

FREE DIE FOR YOU PDF Lisa Unger | 448 pages | 27 Jul 2010 | Random House USA Inc | 9780307476340 | English | New York, United States The Weeknd "Die for You" Sheet Music in C# Minor (transposable) - Download & Print - SKU: MN Sign In. Your high-resolution PDF file will be ready to download in 7 available keys. You'll Be Back. Hamilton: An American Musical. Main Theme from Tenet. Pietschmann, Patrik. Piano Solo. Dead Mom. Beetlejuice [Musical]. Can't Help Falling in Love. Presley, Elvis. Die for You, Conan. Fly Me to the Moon. Sinatra, Frank. Aladdin []. Justin Bieber feat. Chance the Rapper. No Time to Die. Eilish, Billie. Hedwig's Theme. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. Easy Piano. Mary, Did You Know? Lowry, Mark. The Addams Family Musical. Here Comes the Sun. The Beatles. Taylor Swift feat. Bon Iver. Swift, Taylor. Over the Rainbow. Garland, Judy. If I Ain't Got You. Keys, Alicia. A Million Dreams. The Greatest Showman. Before You Go. Capaldi, Lewis. Magnus August Hoiberg. Universal Music Publishing Group. The Weeknd - Starboy. Wicked Games The Weeknd. Elastic Heart Sia feat. View All. Musicnotes Pro Send a Gift Card. Toggle navigation. Die for You on Every Order! Musicnotes Pro. Become a Member Today! Add to Cart. Transpose 7. C Minor Orig. Quick Details. Musicians Like You Also Purchased. Holy Justin Bieber feat. Add Die for You wish list. The Arrangement Details Die for You gives you detailed information about this particular arrangement of Die for You - not necessarily the song. Not the arrangement you were looking for? View All Arrangements.