Display PDF in Separate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Essex Field Club

THE ESSEX FIELD CLUB DEPARTMENT OF LIFE SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF EAST LONDON ROMFORD ROAD, STRATFORD, LONDON, E15 4LZ NEWSLETTER NO. 16 February 1996 FROM THE PRESIDENT How would you describe the aims and activities of the present day Essex Field Club? When the Club first came into being it might not have been that inappropriate to regard its activities as encompassing ‘hunting, shooting and fishing’, the collection of dead voucher specimens of everything living in Essex being one of the Club’s primary objectives. Today however, our members would regard themselves as anything but, members of an organization that might be misconstrued as indulging in ‘field sports’ . Our Club is surely primarily a natural history society, with a present-day emphasis an recording, conservatian and natural history education. Your Council had a special meeting on the 31 January to look at the present and potential future role of the EFC in Essex, debating just how we could give the Club a new attractive image that would give us a steadily increasing membership, and how best we might interrelate to such organisations as the Essex Wildlife Trust, English Nature, the National Biological Records Centre and the local county natural history societies. Particularly in view of our proposed partnership in a new museum on Epping Forest. As a result of this meeting Council will be proposing at the next AGM that the Club should change its name to the ESSEX NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, and redefine its objectives, and rules, in line with its modern image. We propose subtitling the new name with ‘formerly the Essex Field Club’ for a few years, and retention of our ‘speckled wood on blackberry leaf logo’ , to give us continuity. -

APPENDIX 5A – Schedule of Proposed Policies Map Changes June 2019

APPENDIX 5A – Schedule of Proposed Policies Map Changes June 2019 Schedule of Proposed Changes to the Pre-Submission Local Plan Policies Map A Planning Inspector is examining the Chelmsford City Council Local Plan as submitted by the Council on 29 June 2018. As part of the examination process a number of proposed modifications to the Pre-Submission Local Plan have been identified. These modifications are either classified as "main" or "additional" modifications and are set out in the updated main and additional modification schedules, March 2019. The policies map is not defined in statute as a development plan document and so the Inspector does not have the power to recommend main modifications to it. However the Council must maintain an adopted policies map which accurately illustrates geographically the application of the policies in the adopted development plan. Therefore, this schedule sets out a number of changes to the policies map which are in response to specific modifications to policies set out in the main modifications schedule. Other changes are also included to reflect the additional modifications schedule. The related main or additional modification reference number is included in the schedule below. Where changes are factual only there is no main or additional modification reference included. Accompanying this schedule are inset maps showing the specific changes in map form, where applicable. Please note maps have not been produced if the only change is to the title. It should be noted that at the point of adoption the latest OS base mapping will be applied to the policies map and insets. This may result in minor changes occurring to notation boundaries. -

Setting the Council Tax 2017/18;

COUNCIL – 21 February 2017 Item 12 SETTING THE COUNCIL TAX 2017/18 1 SUMMARY 1.1 This report seeks authorisation from Council to set the Council Tax for the year 2017/18. 2 INTRODUCTION 2.1 At the Council Meeting held on 14 February 2017, the Council agreed the revenue budget for 2017/18 within the Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) and Council agreed to increase Council Tax by 1.95%, making an average Band D property charge £217.17. 2.2 In order to set the Council Tax, information is required from Essex County Council, Police and Crime Commissioner, Essex Fire Authority and the Parish and Town Councils. This information is provided in appendices A to E. 3 2017/18 COUNCIL TAX 3.1 When publishing Council Tax figures for local authority areas, it is usual practice to use the Band D charge and an average charge for the Parish/Town Council tax. The 2017/18 charge compared to 2016/17 is shown below:- 2016/17 2017/18 Increase Increase £ £ £ % Essex County Council 1,108.35 1,108.35 - - Essex County Council Social Care Levy 21.78 55.35 33.57 3.00 Essex Fire Authority 67.68 69.03 1.35 1.99 Police & Crime Commissioner 152.10 157.05 4.95 3.25 Town/Parish Councils 41.07 44.39 3.32 8.09 Rochford District Council 213.02 217.17 4.15 1.95 Total 1,604.00 1,651.34 3.2 While the average Band D Charge for the District is £217.17, this will vary across the District due to the differences in the Town/Parish Councils. -

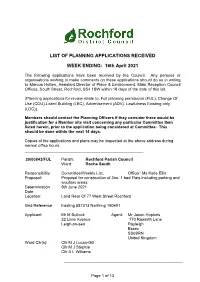

Weekly List of Planing Applications

LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED WEEK ENDING: 16th April 2021 The following applications have been received by the Council. Any persons or organisations wishing to make comments on these applications should do so in writing to Marcus Hotten, Assistant Director of Place & Environment, Main Reception Council Offices, South Street, Rochford, SS4 1BW within 18 days of the date of this list. (Planning applications for review relate to: Full planning permission (FUL), Change Of Use (COU),Listed Building (LBC), Advertisement (ADV), Lawfulness Existing only (LDC)). Members should contact the Planning Officers if they consider there would be justification for a Member site visit concerning any particular Committee Item listed herein, prior to the application being considered at Committee. This should be done within the next 14 days. Copies of the applications and plans may be inspected at the above address during normal office hours. _____________________________________________________ 20/00843/FUL Parish: Rochford Parish Council Ward: Roche South Responsibility: Committee/Weekly List; Officer: Ms Katie Ellis Proposal: Proposal for construction of 3no. 1 bed Flats including parking and ancillary areas. Determination 9th June 2021 Date Location: Land Rear Of 77 West Street Rochford Grid Reference Easting 587313 Northing 190491 Applicant: Mr M Bullock Agent: Mr Jason Hopkins 22 Lime Avenue 170 Rawreth Lane Leigh-on-sea Rayleigh Essex SS69RN United Kingdom Ward Cllr(s): Cllr M J Lucas-Gill Cllr M J Steptoe Cllr A L Williams _____________________________________________________ -

The Pyrenees

The Pyrenees A Greentours Holiday for the Alpine Garden Society 10th to 23rd June 2011 Led by Paul Cardy Trip Report and Systematic Lists by Paul Cardy Day 1 Friday 10 th June Arrival and Transfer to Formigueres Having driven from the south western Alps and reached Carcassonne the previous evening, I continued to Toulouse to meet the group at the airport. I was unexpectedly delayed by French customs who stopped me at the toll booth entering the city. There followed a lengthy questioning, as I had to unpack the contents of my suspiciously empty Italian mini-bus and show them my two large boxes of books, suitcase full of clothes, picnic supplies, etc., to convince them my purpose was a botanical tour to the Pyrenees. Now a little late I arrived breathlessly at Toulouse airport and rushed to the gate to meet Margaret, and the New Zealand contingent of Chris, Monica, Archie and Lynsie, hurriedly explaining the delay. Anyway we were soon back on the motorway and heading south towards Foix. White Storks in a field on route was a surprise. We made a picnic stop at a functional aire where there were tables, and a selection of weedy plants. Black Kite soared overhead. Once past Foix and Ax-les- Thermes the scenery became ever more interesting as we wound our way up to a misty Col de Puymorens. There a short stop yielded Pulsatilla vernalis in fruit and Trumpet Gentians. Roadside cliffs had Rock Soapwort, Saxifraga paniculata , and Elder-flowered Orchids became numerous. Now in the Parc Naturel Régional des Pyrénées Catalanes, a fascinating route down into the valley took us through Saillagouse and Mont-Louis before heading up a minor road to the village of Formigueres, our base for the first three nights. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Proc. VIII. Congr. Eur. Lepid., Helsinki 19-23.IV 1992 Nota lepid. Supplement No. 5 : 51-64 ; 31.X.1994 ISSN 0342-7536 Conserving Britain's rarest moths Paul Waring Windmill View, 1366 Lincoln Road, Werrington, Peterborough, PE4 6LS, UK Summary The work of the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Moth Conservation Project has several components. The first involves servicing a national network of recorders which was set up in the winter of 1990/91 to trawl information on the current national distribution, status and conservation requirements of the rarer species of macro-moths in Britain. The information collected is being used to organise surveys and produce national surveys and produce national distribution maps, data sheets and a bibliography for the rarer moths. The rarer macro-moths have been defined as those species believed to occur in less than one hundred of the 10 km squares in Britain. Approximately 280 of the 730 or more macro-moth species that breed in Britain are in this category now. The collected information is used by the government conservation agencies to identify important breeding sites and advise on their management. Since its inception in 1987 the Moth Conservation Project has also been involved in devising and assisting practical conservation measures for a number of rare moths including six species of moths which receive legal protection in Britain and are listed on Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and 1988 amendment. These six are Zygaena viciae argyllensis Tremewan, Thetidia smaragdaria maritima Prout, Pareulype berberata Denis & Schiffer- müller, Siona lineata Scopoli, Acosmetia caliginosa Hübner and Hadena irregularis Hufnagel. -

The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation

M DC, — _ CO ^. E CO iliSNrNVINOSHilWS' S3ldVyan~LIBRARlES*"SMITHS0N!AN~lNSTITUTl0N N' oCO z to Z (/>*Z COZ ^RIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTlON NOIiniIiSNI_NVINOSHllWS S3ldVaan_L: iiiSNi'^NviNOSHiiNS S3iavyan libraries Smithsonian institution N( — > Z r- 2 r" Z 2to LI ^R I ES^'SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTlON'"NOIini!iSNI~NVINOSHilVMS' S3 I b VM 8 11 w </» z z z n g ^^ liiiSNi NviNOSHims S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution N' 2><^ =: to =: t/J t/i </> Z _J Z -I ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSIdVyan L — — </> — to >'. ± CO uiiSNi NViNosHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution n CO <fi Z "ZL ~,f. 2 .V ^ oCO 0r Vo^^c>/ - -^^r- - 2 ^ > ^^^^— i ^ > CO z to * z to * z ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNl NVINOSHllWS S3iaVdan L to 2 ^ '^ ^ z "^ O v.- - NiOmst^liS^> Q Z * -J Z I ID DAD I re CH^ITUCnMIAM IMOTtTIITinM / c. — t" — (/) \ Z fj. Nl NVINOSHIIINS S3 I M Vd I 8 H L B R AR I ES, SMITHSONlAN~INSTITUTION NOIlfl :S^SMITHS0NIAN_ INSTITUTION N0liniliSNI__NIVIN0SHillMs'^S3 I 8 VM 8 nf LI B R, ^Jl"!NVINOSHimS^S3iavyan"'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN~'lNSTITUTI0N^NOIin L '~^' ^ [I ^ d 2 OJ .^ . ° /<SS^ CD /<dSi^ 2 .^^^. ro /l^2l^!^ 2 /<^ > ^'^^ ^ ..... ^ - m x^^osvAVix ^' m S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION — NOIlfliliSNrNVINOSHimS^SS iyvyan~LIBR/ S "^ ^ ^ c/> z 2 O _ Xto Iz JI_NVIN0SH1I1/MS^S3 I a Vd a n^LI B RAR I ES'^SMITHSONIAN JNSTITUTION "^NOlin Z -I 2 _j 2 _j S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyVaan LI BR/ 2: r- — 2 r- z NVINOSHiltNS ^1 S3 I MVy I 8 n~L B R AR I Es'^SMITHSONIAN'iNSTITUTIOn'^ NOlin ^^^>^ CO z w • z i ^^ > ^ s smithsonian_institution NoiiniiiSNi to NviNosHiiws'^ss I dVH a n^Li br; <n / .* -5^ \^A DO « ^\t PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY ENTOMOLOGIST'S RECORD AND Journal of Variation Edited by P.A. -

Profile for the Parishes Of

Profile for the Parishes of St. Nicholas with St Mary’s Great Wakering Foulness and All Saints with St Mary’s Barling Magna Little Wakering The Profile for the Parishes of Great Wakering with Foulness Island and Barling Magna with Little Wakering 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Priest-in-Charge of our parishes since 2008 has recently assumed the additional role of Priest-in-Charge of the nearby parish of St Andrews Rochford with Sutton and Shopland and taken up residence in the Rochford Rectory. We are looking for an Associate Priest and Team Vicar designate to live in the Great Wakering Vicarage and to work with our Priest-in-charge in the care, support and development of all the parishes. This is a response to the ‘Re-imagining Ministry’ document passed by the Diocesan Synod in March 2013. Our Parishes are close to Shoeburyness and Southend-on-sea. Both have good rail links to London, which is about an hour away and used by commuters. Shoeburyness has the historic Shoebury Garrison, now vacated by the army and re-developed as a residential village which retains the original character. Shoeburyness also has two popular beach areas for bathing, walking or water sports. There are a number of shops and businesses and an Asda supermarket which is served by a bus from Great Wakering. Southend-on Sea is the nearest town. It has two commuter rail lines and an expanding airport. It has the usual High Street stores and new library and university buildings in the town centre. Its long pier is a local attraction and renowned as the longest pleasure pier in the world. -

The Arup Journal

THE ARUP JOURNAL 25TH YEAR SPRING 1990 THEARUP Foreword Povl Ahm JOURNAL Chairman Ove Arup Partnership Vol.25 No.1 Spring 1990 Editor: David J. Brown Published by Art Editor: Ove Arup Partnership Desmond Wyeth FCSD 13 Fitzroy Street, Deputy Editor: London W1 P 680 Caroline Lucas Contents Foreword, The Arup Journal is now beginning its 25th year. It is difficult to believe, since by Povl Ahm 2 it seems only yesterday that Peter Dunican wrote his 'personal view' on the occasion of 10 years of the Journal. At least it seems only yesterday to me. Structural engineering: To some of our younger members it may seem like an eternity. some social and political implications, Sadly, Peter is not here to help to celebrate the birthday of what was so by Peter Dunican 3 definitely his baby. His love for communication and his commitment to this publication was essential for the creation of The Arup Journal in the first Stansted Airport Terminal: instance, and for its continued existence and growth over most of its life. the structure, Fortunately, he has not been alone in this effort. Rosemary Devine saw The by Jack Zunz, Martin Manning, Arup Journal through its first difficult years. Then Peter Haggett took over as David Kaye and Chris Jofeh 7 Editor in September 1968 and managed the difficult task of not only Liffey Valley Bridge, maintaining the high standard that had been set from the beginning, but in by Bill Smyth and John Higgins 16 fact developing and improving it through almost 20 years in charge. -

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Appendix B Chelmsford Supplementary Report

Chelmsford Borough Council Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Appendix B Chelmsford Supplementary Report Report April 2008 Prepared for: Chelmsford Borough Council D115326 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Revision Schedule Mid Essex Strategic Flood Risk Assessment April 2008 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 June 07 Draft Heather Rich Peter Mansell Damon O’Brien Flood Risk Specialist Principal Engineer Technical Director 02 July 07 Final Draft Heather Rich Liz Williams Damon O’Brien Flood Risk Specialist Senior Consultant Technical Director 03 October 07 Final Eleanor Cole Liz Williams Jon Robinson Graduate Hydrologist Senior Consultant Associate Director 04 April 08 Final Eleanor Cole Liz Williams Jon Robinson Graduate Hydrologist Senior Consultant Associate Director Scott Wilson 6-8 Greencoat Place, London, SW1P 1PL Tel: 020 7798 5200 Fax: 020 7798 5001 www.scottwilson.com Chelmsford Borough Council D115326 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment PREFACE Purpose: The purpose of this report is to provide Strategic Flood Risk Assessment (SFRA) information specific to the Chelmsford Borough Council area. It outlines the main flood risks posed to the council area and how the long-term management fluvial flood sources could be addressed by the incorporation of Flood Storage Areas. The flood risks to potential sites have been identified on both greenfield and brownfield sites. Flood Hazard Mapping for South Woodham Ferrers along the River Crouch has been undertaken based on breach simulation modelling. Flood hazard and depth mapping has been provided for the climate change scenarios for the River Chelmer, using recent model information completed by Halcrow Ltd as part of this study. This information should be used in conjunction with guidance in the SFRA to apply the Sequential Test (Planning Policy Statement (PPS) 25: Development and Flood Risk, Communities and Local Government). -

Wallasea Island to Burnham-On-Crouch Report WIB 3: Hawk Hill Bridge to Clementsgreen Creek

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: Wallasea Island to Burnham-on-Crouch Report WIB 3: Hawk Hill Bridge to Clementsgreen Creek Part 3.1: Introduction Start Point: Hawk Hill Bridge, Battlesbridge (Grid reference TQ 7806 9467) End Point: Clementsgreen Creek, South Woodham Ferrers (Grid reference TQ 8195 9693) Relevant Maps: WIB 3a to WIB 3f 3.1.1 This is one of a series of linked but legally separate reports published by Natural England under section 51 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which make proposals to the Secretary of State for improved public access along and to this stretch of coast between Wallasea Island and Burnham-on-Crouch. 3.1.2 This report covers length WIB 3 of the stretch, which is the coast between Hawk Hill Bridge and Clementsgreen Creek. It makes free-standing statutory proposals for this part of the stretch, and seeks approval for them by the Secretary of State in their own right under section 52 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. 3.1.3 The report explains how we propose to implement the England Coast Path (“the trail”) on this part of the stretch, and details the likely consequences in terms of the wider ‘Coastal Margin’ that will be created if our proposals are approved by the Secretary of State. Our report also sets out: any proposals we think are necessary for restricting or excluding coastal access rights to address particular issues, in line with the powers in the legislation; and any proposed powers for the trail to be capable of being relocated on particular sections (“roll- back”), if this proves necessary in the future because of coastal change. -

This Document Has Been Created by AHDS History and Is Based on Information Supplied by the Depositor

This document has been created by AHDS History and is based on information supplied by the depositor SN 3980 - Agricultural Census Parish Summaries, 1877 and 1931 This study contained a limited amount of documentation. The parish codes given below are to be used to interpret the data for the year of 1877. The parish codes for the 1931 data were not given in the initial deposit; consequently it is not possible to establish the parish of origin for the 1931 data.