Tian's "L'année Du Lièvre"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Uncertain Relationship Between International Criminal Law Accountability and the Rule of Law in Post-Atrocity States: Lessons from Cambodia

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 42, Issue 1 Article 1 The Uncertain Relationship Between International Criminal Law Accountability and the Rule of Law in Post-Atrocity States: Lessons from Cambodia Randle C. DeFalco∗ ∗ Copyright c by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj ARTICLE THE UNCERTAIN RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE RULE OF LAW IN POST-ATROCITY STATES: LESSONS FROM CAMBODIA Randle C. DeFalco* ABSTRACT One of the goals routinely ascribed to international criminal law (“ICL”) prosecutions is the ability to improve the rule of law domestically in post-atrocity states. This Article reassesses the common assumption that the relationship between the pursuit of ICL accountability and improving the rule of law in post-atrocity states is necessarily a linear, wholly positive one. It does so through an analysis of the relationship between the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia and the rule of law domestically in Cambodia. Through this analysis, this Article highlights the oft-ignored possibility that ICL prosecutions may actually have a mix of positive, nil, and negative effects on the domestic rule of law, at least in the short run. In the Cambodian context, this Article argues that such risk is quite real and arguably, in the process of being realized. These harmful rule of law consequences are most visible when viewed in light of the particularities of Cambodia’s rule of law deficit, which increasingly stems from government practices of subverting the rule of law through means obscured behind façades of legality. -

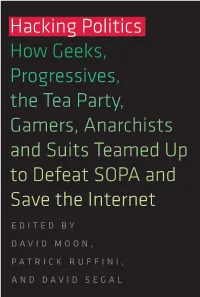

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Borassus Flabellifer Linn.) As One of the Bioethanol Sources to Overcome Energy Crisis Problem in Indonesia

2011 2nd International Conference on Environmental Engineering and Applications IPCBEE vol.17 (2011) © (2011) IACSIT Press, Singapore The Potential of Developing Siwalan Palm Sugar (Borassus flabellifer Linn.) as One of the Bioethanol Sources to Overcome Energy Crisis Problem in Indonesia Nisa Bila Sabrina Haisya 1, Bagus Dwi Utama 2, Riki Cahyo Edy 3, and Hevi Metalika Aprilia 4 1 Student at Faculty of Veterinary, Bogor Agricultural University 2 Student at Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Bogor Agricultural University 3 Student at Faculty of Economy and Management, Bogor Agricultural University 4 Student at Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University Abstract. The energy demand in Indonesia increases due to a significant growth in population, this fact has diminished the fossil fuel storage as our main non renewable energy source. Recently, there are a lot of researches on renewable energy; one of the most prominent is the development of bioethanol as a result of fermentation of sugar or starch containing materials. Palm sugar as one of the natural sugar sources can be obtained from most of palm trees such as coconut, aren, nipah, and siwalan. This paper explored the potential of Siwalan palm sugar development to be converted into bioethanol as renewable energy source through fermentation and purification processes. Siwalan palm sugar contains 8.658 ml ethanol out of 100 ml palm sugar liquid processed using fermentation and distillation. Bioethanol can further utilized as fuel when it is mixed with gasoline that called gasohol. In the future, it is expected that gasohol can replace gasoline consumption as an alternative energy that can be competitive in term of price in Indonesia. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia

Judging the Successes and Failures of the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia * Seeta Scully I. DEFINING A ―SUCCESSFUL‖ TRIBUNAL: THE DEBATE ...................... 302 A. The Human Rights Perspective ................................................ 303 B. The Social Perspective ............................................................. 306 C. Balancing Human Rights and Social Impacts .......................... 307 II. DEVELOPMENT & STRUCTURE OF THE ECCC ................................... 308 III. SHORTCOMINGS OF THE ECCC ......................................................... 321 A. Insufficient Legal Protections ................................................... 322 B. Limited Jurisdiction .................................................................. 323 C. Political Interference and Lack of Judicial Independence ....... 325 D. Bias ........................................................................................... 332 E. Corruption ................................................................................ 334 IV. SUCCESSES OF THE ECCC ................................................................ 338 A. Creation of a Common History ................................................ 338 B. Ending Impunity ....................................................................... 340 C. Capacity Building ..................................................................... 341 D. Instilling Faith in Domestic Institutions ................................... 342 E. Outreach .................................................................................. -

Rj FLORIDA PLANT IMMIGRANTS

rj FLORIDA PLANT IMMIGRANTS OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 15 FAIRCHILD TROPICAL GARDEN THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BORASSUS PALMS INTO FLORIDA DAVID FAIRCHILD COCONUT GROVE, FLORIDA May 15, 1945 r Fruits and male flower cluster of the Borassus palm of West Africa (Borassus ethiopum). The growers of this palm and its close relative in Ceylon are fond of the sweetish fruit-flesh and like the mango eaters, where stringy seedlings are grown, they suck the pulp out from the fibers and enjoy its sweetish flavor. The male flower spikes were taken from another palm; a male palm. Bathurst, Gambia, Allison V. Armour Expedition, 1927. THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BORASSUS PALMS INTO FLORIDA DAVID FAIRCHILD JL HE Borassus palms deserve to be known by feet across and ten feet long and their fruits the residents of South Florida for they are land- are a third the size of average coconuts with scape trees which may someday I trust add a edible pulp and with kernels which are much striking tropical note to the parks and drive- appreciated by those who live where they are ways of this garden paradise. common. They are outstanding palms; covering vast areas of Continental India, great stretches They attain to great size; a hundred feet in in East and West Africa and in Java, Bali and height and seven feet through at the ground. Timor and other islands of the Malay Archi- Their massive fan-shaped leaves are often six pelago. &:••§:• A glade between groups of tall Palmyra palms in Northern Ceylon. The young palms are coming up through the sandy soil where the seeds were scattered over the ground and covered lightly months before. -

Justice and the Khmer Rouge

Justice and the Khmer Rouge: concepts of just response to the crimes of the democratic Kampuchean regime in buddhism and the extraordinary chambers in the courts of Cambodia at the time of the Khmer Rouge tribunal Gray, Tallyn 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Gray, T. (2012). Justice and the Khmer Rouge: concepts of just response to the crimes of the democratic Kampuchean regime in buddhism and the extraordinary chambers in the courts of Cambodia at the time of the Khmer Rouge tribunal. (Working papers in contemporary Asian studies; No. 36). Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University. http://www.ace.lu.se/images/Syd_och_sydostasienstudier/working_papers/Gray_Tallyn.pdf Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Your Guide To

Your Guide to Sengkang Riverside Park is one of four parks located on the North Eastern Riverine Loop of the Park Connector Network. Punggol Reservoir, known as Sungei Punggol in Tips for a safe and enjoyable trip the past, runs through the park. • Dress comfortably and wear suitable footwear. • Wear a hat, put on sunglasses and apply sunscreen to shield yourself from the sun. This walking trail brings you on an educational journey to explore 20 fruit trees, some • Spray on insect repellent if you are prone to insect bites. of which bear fruits that cannot be found in local fruit stalls and supermarkets. Part • Drink ample fluids to stay hydrated. of the trail goes round the park’s centrepiece, a constructed wetland with manually • Walk along the designated paths to protect the natural environment of the park. planted marshes and rich biodiversity. The constructed wetland collects and filters • Dispose of rubbish at the nearest bin. rainwater naturally through its aquatic plants. It doubles up as a wildlife habitat and • Activities such as poaching, releasing and feeding of animals, damaging and removal of plants, and those attracts a variety of mangrove birds and damselflies. that cause pollution are strictly prohibited. • Clean up after your pets and keep them leashed. • Camping is not allowed. Difficulty level:Easy Distance: 1.4km Walking time: 1-2hr • Cycling time: 30min 2 Tampines Expressway 1 2 3 4 Visitor Plot Mangosteen Tree Soursop Tree Oil Palm Wine Palm Civic Plot 12 11 10 8 9 5 6 7 8 Constructed 6 Wetland 13 Lemon Tree Ordeal -

Borassus Flabellifer Linn) in Jeneponto District, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

Journal of Tropical Crop Science Vol. 3 No. 1, February 2016 www.j-tropical-crops.com Conservation Status of Lontar Palm Trees (Borassus flabellifer Linn) In Jeneponto District, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Sukamaluddin*, Mulyadi, Gufran D.Dirawan, Faizal Amir, Nurlita Pertiwi Department of Environmental Education Studies, Makassar State University, Indonesia *Corresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract of South Sulawesi where the lontar palm trees have become a symbol of the area. Lontar palm trees can This study aimed to describe the botanical description, be found in almost all parts of Jeneponto district, but conservation status and potentials of Sulawesi particularly in the sub-districts of Bangkala, Tamalatea native lontar palm trees (Barassus flabellifer Linn) and Binamu. However, plantings and growth pattern in Jeneponto district, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. of the trees can be irregular throughout the region. It This study was extended to include a study on the takes between 10 and 20 years for the lontar palm community’s attitude towards preservation of lontar trees to reach maturity. palm trees involving 30 people distributed over three research sites. Overall 53% of the dry-land in Records of BPS (Central Statistics Agency) Jeneponto district is grown by lontar palm trees with Jeneponto 2009-2012 reported that in recent times the tree density ranging from 50 trees per ha for trees the area under lontar plam trees in Jeneponto district aged between 1-5 years; 37 trees per ha for trees has been reduced by more than 16%, from 422 ha to aged between 5-10 years; and 32 trees per ha for 363 ha. -

Habitat for Conservation of Baya Weaver Ploceus Philippinus

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Communfcatfon Tradftfonal home garden agroforestry systems: habftat for conservatfon of Baya Weaver Ploceus phflfppfnus (Passerfformes: Plocefdae) fn Assam, Indfa Yashmfta-Ulman, Awadhesh Kumar & Madhubala Sharma 26 Aprfl 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 4 | Pp. 10076–10083 10.11609/jot. 3090 .9. 4.10076-10083 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 April 2017 | 9(4): 10076–10083 Traditional home garden agroforestry systems: Communication habitat for conservation of Baya Weaver Ploceus philippinus ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) (Passeriformes: Ploceidae) in Assam, India ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Yashmita-Ulman 1, Awadhesh Kumar 2 & Madhubala Sharma 3 OPEN ACCESS 1,2,3Department of Forestry, North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology, Nirjuli, Arunachal Pradesh 790109, India [email protected], [email protected] (corresponding author), [email protected] Abstract: The present study was conducted in 18 homegarden agroforestry systems of Assam to assess the role in the conservation of Baya Weaver Ploceus philippinus. -

Xavier Newswire Volume XCV Published Since 1915 by the Students of Xavier University Issue 24

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 2010-03-17 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (2010). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 588. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/588 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. March 17, 2010 XAVIER NEWSWIRE Volume XCV Published since 1915 by the students of Xavier University Issue 24 Student art in Cohen Courtside chats Read about art from students of Andrew Chestnut and Doug Tifft go head- AlwaYS ONLINE: all majors and years, ranging from to-head to discuss March Madness, Xavier’s sculptures to paintings. tournament chances and meatballs. xavier.edu/ A&E, pg 11 FEATURE, pg 12 newswire inside @ Men’s and women’s basketball Shooting occurs near Village apt. complex Suspect, a non-student, fled into apartment complex early Tuesday BY MEGHAN BERNEKING ment posted Tuesday morning. looked out the window, though, News Editor The subject did not sustain any there were no sirens or anything,” injuries and there were no known Masters said. Residents of the Village may student witnesses. Campus Police Cincinnati Police also respond- have been awakened to the fright- uncovered three shell casings be- ed to the reported gunshots and ening sound of gunshots early tween the Women’s Center and took the subject, who has out- Tuesday morning. -

Korea and the Global Struggle for Socialism a Perspective from Anthropological Marxism

Korea and the Global Struggle for Socialism A Perspective from Anthropological Marxism Eugene E Ruyle Emeritus Professor of Anthropology and Asian Studies California State University, Long Beach Pablo Picasso, Massacre in Korea (1951) CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................. 2 What Is Socialism and Why Is It Important? .................................................. 3 U.S. Imperialism in Korea ...................................................................................18 Defects in Building Socialism in Korea ..........................................................26 1. Nuclear weapons 2. Prisons and Political Repression 3. Inequality, Poverty and Starvation 4. The Role of the Kim family. Reading “Escape from Camp 14.” A Political Review.................................37 For Further Study:.................................................................................................49 References cited.....................................................................................................50 DRAFT • DO NOT QUOTE OR CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION Introduction Even on the left, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) is perhaps the most misunderstood country on our Mother Earth. Cuba and Vietnam both enjoy support among wide sectors of the American left, but north Korea is the object of ridicule and scorn among otherwise intelligent people. In order to clear away some of the misunderstanding, we can do no better than quote