ALBERTA LAW REPORTS Sixth Series Reports of Selected Cases from the Courts of Alberta and Appeals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATTERS the 2000 Reportcard F D- D+ D+ D+ D+ C- C- C C C+ B B Continued Onpage2 N/A F D+ D D+ C+ C- D+ C C- C- C+ C Reviews The

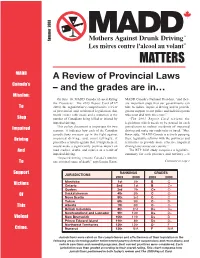

Summer 2003 MATTERS MADD A Review of Provincial Laws Canada’s – and the grades are in… Mission: On June 10, MADD Canada released Rating MADD Canada’s National President, “and there the Provinces: The 2003 Report Card (RTP are important steps that our governments can To 2003), the organization’s comprehensive review take to reduce impaired driving and to provide of provincial and territorial legislation that greater support to our police and judicial system would ensure safer roads and a reduction in the who must deal with this crime.” Stop number of Canadians being killed or injured by “The 2003 Report Card reviews the impaired driving. legislation which needs to be passed in each Impaired This policy document is important for two jurisdiction to reduce incidents of impaired reasons: it indicates how each of the Canadian driving and make our roads safer to travel.” Mrs. jurisdictions measure up in the fight against Knox adds, “MADD Canada is actively pursuing Driving impaired driving; and, most tellingly, it these legislative reforms with the provinces and prescribes a reform agenda that, if implemented, territories to provide more effective impaired would make a significantly positive impact on driving laws across our country.” And road crashes, deaths, and injuries as a result of The RTP 2003 study comprises a legislative impaired driving. summary for each province and territory – it “Impaired driving remains Canada’s number To one criminal cause of death,” says Louise Knox, ––––––––––––––––––– Continued on page 2 Support RANKINGS GRADES JURISDICTIONS 2003 2000 2003 2000 Victims Manitoba 1st 4th B C Ontario 2nd 1st B C+ Quebec 3rd 7th C+ C- Of Saskatchewan 4th 5th C C- Nova Scotia 5th 3rd C C Yukon 6th 9th C- D+ This Alberta 7th 6th C- C- British Columbia 8th 2nd D+ C+ Newfoundland and Labrador 9th 10th D+ D+ Violent New Brunswick 10th 11th D+ D Prince Edward Island 11th 8th D+ D+ Northwest Territories 12th 12th D- F Crime. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1986

Іі$Ье(і by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association! ШrainianWeekl v ; Vol. LIV No. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 24, 1986 25 cents Clandestine sources dispute Israel indirectly approaches USSR official Chornobyl information for help in Demjanjuk prosecution ELLICOTT CITY, Md. — The first For unexplained reasons, foreign JERSEY CITY, N.J. — Israeli offi- The card, which was used in the samvydav information has reached the radio broadcasts were difficult to pick cials have reportedly indirectly ap- United States by the Office of Special West about the accident at the Chor- up and understand within a 30-kilo- proached the Soviet Union for assis- Investigations in its proceedings against nobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine in meter radius of the Chornobyl plant. tance in their case against John Dem- Mr. Demjanjuk, has been the subject of late April. This information disputes Thus, many listeners could not take ad- janjuk, the former Cleveland auto- much controversy. The Demjanjuk many pronouncements by the Soviet vantage of the news and advice broad- worker suspected of being "Ivan the defense contends it is a fraud and that government, reported Smoloskyp, a cast from abroad. Terrible," a guard at the Treblinka there is evidence the card was altered. quarterly published here. Although tens of thousands of death camp known for his brutality. In fact, Mark O'Connor, Mr. Dem- Following is Smoloskyp's story on school-age children were sent from Kiev The Jerusalem Post reported on janjuk's lawyer, had told The Weekly the new samvydav information. to camps on the Black Sea early, pre- August 18 that State Attorney Yona earlier this year that the original ID card According to these underground school children — who are most threat- Blattman had reportedly asked an was never examined by forensic experts. -

Dr. Natalia Rebecca Archer

DR. NATALIA REBECCA ARCHER EDUCATIONAL & ACADEMIC BACKGROUND Fellow of the American College of Dentists (ACD) San Francisco, Sept 2019 Fellow of the Pierre Fauchard Academy Fellow of the IADFE International Academy of Dental-Facial Esthetics Fellow of the International College of Dentists and the International Congress of Dentists StJohn’s Newfoundland, August Certification in Intravenous Conscious Sedation, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York,2001 Doctorate of Dental Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry Dalhousie University,Halifax, Nova Scotia,2001 Valedictorian, Bachelor of Science, Degree in Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1995 Bachelor of Arts ,Degree in Sociology , Dalhousie University , Academic Scholarship, Halifax, NovaScotia ACADEMIC HONOURS & AWARDS Three Best Dentists in Toronto,threebestrated.ca,2019, 2018, 2017 One of the Top Ten Toronto Dentists according to RateMDs in 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 Top Ten Dentists in Toronto according to YELP in 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 Now Magazine's Best Toronto Dentist in2016 Top Dental Dynamo2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 Top 5 Dentists in TorontoMy City Gossip,2015 Open Care National Patients’ Choice Awards, Top Dental Dynamo in Toronto,2019, 2018,2017, 2016, and 2015 3 Best Dentists in Toronto,threebestrated.ca,2015 Top 10 Dentists in Toronto, Ontario - RateMDs2017, 2016, 2015 City Gossip Top 5 Dentist in Toronto,2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 The Award of Merit, Ontario Dental Association,2014 GrowWellTop Toronto Dentist,2014 OpenCare Patients’ Choice -

Sakimay Girl in Run for Miss Teen Canada by Sarah Pacio Grasslands News

Whitewood Inn Restaurant, Bar & Grill open for Һ j33199;!8ধ2+!;¤Wj,32'f¤ff¤ $150 PER COPY (GST included) www.heraldsun.ca Publications Mail Agreement No. 40006725 -YPKH`1\S` Serving Whitewood, Grenfell, Broadview and surrounding areas • Publishing since 1893 =VS0ZZ\L Sakimay girl in run for Miss Teen Canada By Sarah Pacio Grasslands News A young woman from Sakimay First Nation is on the road to national recognition. Despite fre- quent migraines caused by a brain tumor, Dannicka Kequahtooway is striving to live a cheerful and rich life filled with interesting experiences. Dannicka will be entering Grade 11 this fall and lives with her parents, Crystal and Bruce, on a farm outside of Broadview. At age 6, she was diagnosed with an inoperable frontal-temporal brain tumor. Doctors said that this type of tumor typically rup- tures between the ages of 26 and 30, so every six months Dannicka un- dergoes an MRI scan. The tumor has not grown and seizures have decreased since the diagnosis, but she still suffers from severe head- aches and some memory loss. In spite of these challenges, Dannicka continues to push herself and accept whatever opportunities come her way, including the chance to be crowned Miss Teen Canada. Earlier this year, Miss Canada Globe Productions con- tacted Dannicka and inquired whether she would be interested in participating in the Miss Teen Canada pageant, the preliminary event for Miss Teen Universe. Contestants must be 13 – 17 years old and enrolled in a high school or post-secondary program. They must be a Canadian citizen or permanent resi- dent and be good role models. -

Ashleybrodeur-Performanceresume-1-1 Copy.Pages

ASHLEY BRODEUR Contact: 647-529-6188 Eye Colour: Blue Hair E-mail: [email protected] Colour: Brunette DANCE Just Dance 2014 Launch Party Dancer Scott Fordham/ Garnier Budlight Sensation Launch Dancer Mosaic/ Labatt MMVA’s 2013 Dancer PSY/ Universal Music Choreographer’s Ball Dancer Esie Mensah Choreographer’s Ball Dancer Leah Totten/BOSS Dance Company “Son of a Gun” The Bazaar Dancer Leah Totten/BOSS Dance Company “Song For Torah Jane” Dancer Bravo! Fact Dubai Shopping Festival “Living Frames” Dancer CMART Worldwide/Hollywood Jade Salon Des Artistes “Tigerlady” Dancer Esie Mensah/shePRODCUTIONSltd Cultureshock Washington, DC Espy Dancer Lineen Duong Flashmob Dancer CTV Calgary Step Up 4 Revolution Dancer DaCosta Vancouver Calgary Stampede Dancer The Groove Academy SAM Awards Dancer The Groove Academy Enmax Holiday Gala Dancer iLLFX Entertainment Flames Home Opener Dancer The Groove Academy Footprints Dancer Decidedly Jazz Danceworks Hotel 2011 Dancer Thomas Lynch Events Thank You! Dancer Bollywood Film/ EIA Metro Dancer Toronto Fringe Festival Beats, Breaks and Culture Dancer Hollywood Jade Coko Galore Pride 2010 Footprints Dancer Diana Viselli Fashion Has No Borders Dancer Decidedly Jazz Danceworks Possessed Dancer Ashley "Colours" Perez The Bazaar Dancer Decidedly Jazz Danceworks Dusk Dances Toronto Dancer Lindsay Ritter/ Kyle Kass The Golden Tour Dancer Irvin “Max” Washington Swagger Like Us Pride 2009 Dancer Kay Ann Ward/ Pinup Saints Enigma Montreal Dancer Kay Ann Ward “Girl’s Trippin’” Video Dancer Shameka Blake (AIM) The Bazaar Dancer Jordan “Jman” Francis Kuumba Festival Dancer Shameka Blake (AIM) Dancing Down the Decades Dance Dancer Kay Ann Ward It Out! Pilot Dancer/Vocalist GBC Graduate Show Pepsi Max Promotional Dancer Hollywood Jade/ Lineen Duong Talent Defined Dancer Anthony Smith 106 & York Dancer Kay Ann Ward/ City Dance Corps Lyzabeth Lopez FAME Dancer Robert DeOlivera Canadian Jazz Team Dancer Shameka Blake (AIM) Canadian Tap Team Dancer Karyn Ringler/ Darlene Brodeur (CNDC) Dancer Mathew Clark/ CNDC TRAINING Waacking Sharing 2019 St. -

Minutes of a Meeting of the Kamloops Parks and Recreation Committee Held on Wednesday, April 21, 2011 in the Tournament Capital Centre, Meeting Room "D", at 7:00 Am

MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE KAMLOOPS PARKS AND RECREATION COMMITTEE HELD ON WEDNESDAY, APRIL 21, 2011 IN THE TOURNAMENT CAPITAL CENTRE, MEETING ROOM "D", AT 7:00 AM PRESENT: D. Walsh, Councillor B. Edwards, Acting Chair B. Berger, Arts and Community Development Manager C. Fitzmaurice, Recording Secretary B. McCorkell, Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Services Director J. Putnam, Parks, Recreation Facilities, Business Operations Manager L. Bosch C. Bruce P. Doyle P. Kaatz P. King R. Sharp REGRETS: J. Cowden, School District No. 73 R. Lucas GUESTS: D. Freeman, Assistant Development and Engineering Services Director/Real Estate Manager D. Trawin, Development and Engineering Services Director H. Grieve, Vice President, Kamloops Heritage Railway Society G. Wideman, President, Kamloops Heritage Railway Society RECOMMENDATION: That Council Approve: a) The following Winter Games Legacy Grant Applications: • Gavin Coyne requesting assistance to attend the North American Long Track Competitions in Millwaukee, USA, January 26 - 30, 2011 $150 • Joey Burton requesting assistance to attend the Canadian National Cross Country Skiing Championships in Canmore, AB, March 13 - 20, 2011 $150 • Graeme Gordon requesting assistance to attend the Western Challenge Figure Skating Event in Mississauga, ON, December 1 - 5, 2010 $150 • Kamloops Long Blades requesting assistance to attend the BC Long Track Speed Skating Challenge in Fort St. John, BC, January 13 - 16, 2011 $300 T:\PRCS\ADM\MIN\2011\PRC 04 21.docx KAMLOOPS PARKS AND RECREATION COMMITTEE April 21, 2011 -

Join Rotary Now!

The Rotary Club of Toronto Volume 101 | Issue 1 | July 12, 2013 Today’s Program Forward into Our Second Century The Presidential Address – by President Richard White Speaker Here we are at the beginning of our second century. The Club has had an President Richard White exciting and rewarding Centennial Year during which we gave away over a Host $1 million, had many special events and lots of good press. We raised our Peter Love profile in the City of Toronto, with Rotary District 7070 and with Rotary International. We also celebrated our accomplishments going back to 1912 – Location major events and amazing projects that the Club has undertaken in the past. The Imperial Room, We have an enviable legacy to live up to. The Fairmont Royal York Hotel The Rotary Club of Toronto is a living entity. How do we go forward from Richard White here? There is a danger in becoming complacent and reverting to doing joined Thethings that same old way. It is important to examine everything that we do and determine if we can Rotary Club of do it better or in a different, more effective way. We will shortly have a dynamic strategic plan in place Toronto in June which will carry us into our second hundred years. During the past few years, we have expanded our 1996. He served horizons, launched many successful projects and gained valuable experience in running events and as a member, the Club itself. We need to build on these strengths and embrace and use new tools such as social Vice Chair and media to further the goals of the Club and its members. -

What Canadians Think of Beauty Pageants

CANADIAN PRESS / LEGER MARKETING What Canadians Think of Beauty Pageants Report February 2003 507, place d’Armes, bureau 700, Montréal (Québec) H2Y 2W8 Tél. : 514-982-2464 Télec. : 514-987-1960 www.legermarketing.com 1.0 Study Highlights One Canadian in five watches beauty pageants. Question: Do you watch beauty pageants such as Miss Canada International or Miss Teen Canada? Don’t know / n=1501 YES NO Refusal Canada 19% 80% 1% Beauty would be the most important qualification for a pageant. Question: In your opinion, what are the necessary qualities for participating in this kind of competition? n=1501 TOTAL Beauty 46% Intellectual skills 26% Personality 18% Specific talents (singing, dancing) 11% Fitness 9% Public speaking ability 5% Social interests 4% Others 14% Don’t know 31% Refusal 5% Note: As the respondents were able to mention several qualities, the vertical total exceeds 100%. Does the most beautiful win? Opinions are mixed. Question: Do you think the pageant winners are the…? n=1501 TOTAL … most beautiful 20% … most intelligent 5% … most talented 7% All three the same 32% None 10% Don’t know 21% Refusal 5% 2 A quarter of Canadians think the winner is picked in advance. Question: Do you think the organisers have already chosen who will win before the pageant takes place? Don’t know/ n=1501 YES NO Refusal Canada 25% 46% 29% According to 18% of Canadians, beauty pageant contestants have to perform special favours to win the contest. Question: Do you think pageant participants have to do special favours for some of the organisers or jury members in order to win the pageant? Don’t know / n=1501 YES NO Refusal Canada 18% 51% 31% 3 2. -

Book Publisher 90'S

Yellowknife Catholic Separate School System 1952-2002 The 90’s...Diamonds The Nineties Page Yellowknife Catholic Separate School System 1952-2002 The 1990's had some of the best and some of the worst times However, despite the optimism, parts of the economy faltered early for Yellowknifers as we gained a high profile to many other in the decade. In 1991, the city's vacancy rate jumped from 1.2% to parts of the world. Some of the attention was brought on by 7.6 % between April and October. Then, less than 12 months later, negative events. Fortunately, more attention was generated by we lost some significant businesses when the IGA, MacLeod's and events that were extremely positive and they pushed the North the Northern Store, (formerly The Bay), along with the old Miner's and Yellowknife into the forefront of interest and attention for Mess in the Yellowknife Inn, all closed their doors. In addition, Con much of the rest of the world. mine laid off 42 employees and Treminco, just north of Yellowknife, dismissed six more. On the negative side, the Giant Mine strike, which started in May of 1994, shook Yellowknife and shocked the rest of the Decentralization of the GNWT slowed growth in YK ut the country when in September a deliberate explosion killed nine downturn didn’t last and optimism for Yellowknife’s future employees at the Royal Oak, (formerly Giant) mine. returned when Fortunately, though that was by far our worst hour, it wasn't Then, just when it was needed the most, diamond mining opened our only significant one. -

Hansard of Today, Mr

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN December 4, 1984 The Assembly met at 2 p.m. Prayers ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS INTRODUCTION OF GUESTS HON. MR. PICKERING: — Mr. Speaker, it gives me a great deal of pleasure to introduce to you, and through you and to all members of this Assembly, 23 grade 12 high school students from the town of Avonlea. They are accompanied here today by their teacher Karen Bedford and Georgia Jooristy, bus driver David Prohar. I will be meeting with the group following question period in the rotunda area for pictures and then for drinks in the members' dining-room. I would hope the group have an enjoyable stay in the legislature here and perhaps find question period informational and perhaps educational. Some days it's fairly lively, and I think this will be no exception. I look forward to meeting with you, and ask all members to join with me in wishing them a pleasant welcome and stay in the legislature and a safe journey back home. Thank you. HON. MEMBERS: — Hear, hear! HON. MR. FOLK: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. On behalf of the Minister of Education and the MLA for Swift Current, it gives me a great deal of pleasure today to introduce to you and through you to the members of this Assembly, Miss Teen Canada 1984, Karen MacBean, from Swift Current. HON. MEMBERS: — Hear, hear! HON. MR. FOLK: — She is accompanied by her parents, Frank and Colleen MacBean. Would they please stand. HON. MEMBERS: — Hear, hear! HON. MR. FOLK: — I had the pleasure of having lunch with Miss Teen Canada and her parents, and believe me, Mr. -

Volume 21 No. 3

.. p] "CANNOW YOUYOUC!FEELIT" 14.CAWeekly Ipi LIGHTHOUSEON GRT1230.61 50 CENTS niversarytheTuesdayIndustry industry Febat ato 19thbanquet honour was heldaRPM'shonours day in set theTenth aside Centen- An- for RPM's tenthyear MarchVolume 2, 21 1974 No. 3 followedsembledApproximatelynial Ballroom byfor a a fullof cocktailthree the-course hundredInn reception On banquet. The guests whichPark. Later as-was in theRPM'singGrealis.the industryeveningwas ten MasterRon years afor Newman,number of hisand ceremonies talents roasted of knownspeakers at publisher entertaining.for throughout thereviewed even- Walt Moon,PaulGuest White, speakersSteve Bruce Lappin included: Davidsen (Billboard/Los Mel (Vancouver), Shaw, Angeles), Harold Sam orwof piwratiort mediocrity,the inophcis of competent, ,A dairwenthtltau`, Wilson,FranSniderman, ken Johnny (CRTC/Ottawa), Stan Murphy, Klees, Ed Carroll Allan Preston, Baker,Slaight, Sjef and Vic artisaniwhoof havemind, and alteady byrlteir all dr111M4111101. thme ofpundit%ecutbk,', theCurtolaHeBeforeTerry Hillcresthad McGee. thegreeted to hurryfestivities in Hamilton.the off crowdfor got his underway, andengagement toasted Bobby RPM. at inspireduleitetwaitand TheofedThroughout the with event anniversary. numerous came the evening,about plaques through RPM ana wasmomentoesthe effortshonour- mitteeAnniversaryof a group wasTENTH callingcomprised Banquet YEARthemselves Committee.of continuedGlenda The RoyTheTenth on (RCA),Com-page 6 GrealisLarge plaque on behalf emblazoned of the industry with masthead by Vic Wilson -

Dr. Natalia Rebecca Archer

DR. NATALIA REBECCA ARCHER EDUCATIONAL & ACADEMIC BACKGROUND Fellow of the American College of Dentists (ACD) San Francisco, Sept 2019- current Fellow of the Pierre Fauchard Academy, 2018- current Fellow of the IADFE (International Academy of Dental-Facial Esthetics)-current Fellow of the International College of Dentists and the International Congress of Dentists St. John’s Newfoundland, August 2015-current Certification in Intravenous Conscious Sedation, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York, 2001 Doctorate of Dental Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2001 Valedictorian, Bachelor of Science, Degree in Biology, DalhousieUniversity, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1995 Bachelor of Arts, Degree in Sociology, Dalhousie University , Academic Scholarship, Halifax, NovaScotia ACADEMIC HONOURS & AWARDS Three Best Dentists in Toronto,threebestrated.ca, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2015 One of the Top Ten Toronto Dentists according to RateMDs in 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 Top Ten Dentists in Toronto according to YELP in 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 Now Magazine's Best Toronto Dentist in 2016, 2013 Top Dental Dynamo 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 Top 5 Dentists in Toronto My City Gossip, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 Open Care National Patients’ Choice Awards, Top Dental Dynamo in Toronto, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015 Top 10 Dentists in Toronto, Ontario - RateMDs 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 City Gossip Top 5 Dentist in Toronto, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 The Award of Merit, Ontario