Patterns of Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting a Person with Washing and Dressing

Factsheet 504LP Supporting a January 2021 person with washing and dressing As a person’s dementia progresses, they will need more help with everyday activities such as washing, bathing and dressing. For most adults, these are personal and private activities, so it can be hard for everyone to adjust to this change. You can support a person with dementia to wash and dress in a way that respects their preferences and their dignity. This factsheet is written for carers. It offers practical tips to help with washing, bathing, dressing and personal grooming. 2 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Contents n How dementia affects washing and dressing — Focusing on the person — Allowing enough time — Making washing and dressing a positive experience — Creating the right environment n Supporting the person with washing and bathing — How to help the person with washing, bathing and showering: tips for carers — Aids and equipment — Skincare and nails — Handwashing and dental care — Washing, drying and styling hair — Hair removal — Using the toilet n Dressing — Helping a person dress and feel comfortable: tips for carers — Shopping for clothes together: tips for carers n Personal grooming — Personal grooming: tips for carers n When a person doesn’t want to change their clothes or wash n Other useful organisations 3 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Supporting a person with washing and dressing How dementia affects washing and dressing The way a person dresses and presents themselves can be an important part of their identity. Getting ready each day is a very personal and private activity – and one where a person may be used to privacy, and making their own decisions. -

Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel

Core Concepts for Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel 1 Presenter Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control Trinity Health, Livonia, MI Contributions by Heather M. Gilmartin, NP, PhD, CIC Denver VA Medical Center University of Colorado Laraine Washer, MD University of Michigan Health System 2 Learning Objectives • Outline the importance of effective hand hygiene for protection of healthcare personnel and patients • Describe proper hand hygiene techniques, including when various techniques should be used 3 Why is Hand Hygiene Important? • The microbes that cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be transmitted on the hands of healthcare personnel • Hand hygiene is one of the MOST important ways to prevent the spread of infection 1 out of every 25 patients has • Too often healthcare personnel do a healthcare-associated not clean their hands infection – In fact, missed opportunities for hand hygiene can be as high as 50% (Chassin MR, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2015; Yanke E, Am J Infect Control, 2015; Magill SS, N Engl J Med, 2014) 4 Environmental Surfaces Can Look Clean but… • Bacteria can survive for days on patient care equipment and other surfaces like bed rails, IV pumps, etc. • It is important to use hand hygiene after touching these surfaces and at exit, even if you only touched environmental surfaces Boyce JM, Am J Infect Control, 2002; WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, WHO, 2009 5 Hands Make Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Other Microbes Mobile (Image from CDC, Vital Signs: MMWR, 2016) 6 When Should You Clean Your Hands? 1. Before touching a patient 2. -

WASH Pledge: Guiding Principles a Business Commitment to WASH

WASH Pledge: Guiding principles A business commitment to WASH In collaboration with 22 WASHWASH Pledge:Pledge: GuidingGuiding principlesprinciples Contents Foreword | 4 Summary | 5 Introduction | 6 WBCSD Pledge for access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene | 9 Guiding principles | 10 Guidance on water, sanitation and hygiene at the workplace | 13 WASH at the workplace: points of reference for WASH Pledge self-assessment | 13 1. General 13 2. Workplace water supply 14 3. Workplace sanitation 15 4. Workplace hygiene and behavior change 16 5. Value/supply chain WASH 17 6. Community WASH 17 Educational and behavior change activities | 18 WASH across the value chain | 20 WASH Pledge self-assessment tool for business | 24 3 WASH Pledge: Guiding principles Foreword Today, over 785 million people healthier population and increased and quality, within their operations are still without access to safe productivity.3 and across their value chain, in drinking water, another 2.2 billion all global markets. As employers lack safely managed drinking A proposed first step in and members of society, we water services and an estimated accelerating business action is for encourage businesses to 4.2 billion lack access to safely companies to commit to WBCSD’s commit to the Pledge to ensure managed sanitation services.1 Pledge for Access to Safe Water, appropriate access to safe water, This is incompatible not only Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH sanitation and hygiene for their with the World Business Council Pledge). This Pledge aims to have own employees, thus making a for Sustainable Development’s businesses commit to securing direct contribution to addressing (WBCSD) Vision 2050, where nine appropriate access to safe WASH one of the most pressing public billion people are able to live well for all employees in all premises health challenges of our times. -

Clean Your Hands in the Context of Covid-19

WHO SAVE LIVES: CLEAN YOUR HANDS IN THE CONTEXT OF COVID-19 Hand Hygiene in the Community You can play a critical part in fighting COVID-19 • Hands have a crucial role in the transmission of COVID-19. • COVID-19 virus primarily spreads through droplet and contact transmission. Contact transmission means by touching infected people and/or contaminated objects or surfaces. Thus, your hands can spread virus to other surfaces and/or to your mouth, nose or eyes if you touch them. Why is Hand Hygiene so important in preventing infections, including COVID-19? • Hand Hygiene is one of the most effective actions you can take • Community members can play a critical role in fighting COVID-19 to reduce the spread of pathogens and prevent infections, by adopting frequent hand hygiene as part of their day-to-day including the COVID-19 virus. practices. https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/safehands-challengeJoin the #SAFEHANDS challenge now and save lives! Post a video or picture of yourself washing your hands and tag #SAFEHANDS https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/interim-recommendations-on-obligatory-hand-hygiene-against-transmission-of-covid-19WHO calls upon policy makers to provide • the necessary infrastructure to allow people to eectively perform hand hygiene in public places; • to support hand hygiene supplies and best practices in health care facilities. Hand Hygiene in Health Care Why is it important to participate in the WHO global hand hygiene campaign for the fight against COVID-19? • The WHO global hand hygiene campaign SAVEhttps://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/ LIVES: Clean Your Hands mobilizes people around the world to increase adherence to hand hygiene in health care facilities, thus protecting health care workers and patient from COVID-19 and other pathogens. -

NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), Especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment

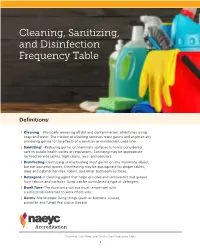

Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table Definitions1 › Cleaning2 –Physically removing all dirt and contamination, oftentimes using soap and water. The friction of cleaning removes most germs and exposes any remaining germs to the effects of a sanitizer or disinfectant used later. › Sanitizing3 –Reducing germs on inanimate surfaces to levels considered safe by public health codes or regulations. Sanitizing may be appropriate for food service tables, high chairs, toys, and pacifiers. › Disinfecting–Destroying or inactivating most germs on any inanimate object, but not bacterial spores. Disinfecting may be appropriate for diaper tables, door and cabinet handles, toilets, and other bathroom surfaces. › Detergent–A cleaning agent that helps dissolve and remove dirt and grease from fabrics and surfaces. Soap can be considered a type of detergent. › Dwell Time–The duration a surface must remain wet with a sanitizer/disinfectant to work effectively. › Germs–Microscopic living things (such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi) that cause disease. Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table 1 Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfecting Frequency Table1 Relevant to NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment Before After Daily Areas each each (End of Weekly Monthly Comments4 Use Use the Day) Food Areas Clean, Clean, Food preparation Use a sanitizer safe for and then and then surfaces food contact Sanitize Sanitize If washing the dishes and utensils by hand, Clean, use a sanitizer safe -

Euthenics, There Has Not Been As Comprehensive an Analysis of the Direct Connections Between Domestic Science and Eugenics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics Caleb J. true University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons true, Caleb J., "Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 730. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/730 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented by CALEB J. TRUE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2011 History © Copyright by Caleb J. True 2011 All Rights Reserved EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented By Caleb J. True Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________ Laura L. Lovett, Chair _______________________________ Larry Owens, Member _______________________________ Kathy J. Cooke, Member ________________________________ Joye Bowman, Chair, History Department DEDICATION To Kristina. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Laura L. Lovett, for being a staunch supporter of my project, a wonderful mentor and a source of inspiration and encouragement throughout my time in the M.A. -

UNICEF's Strategy for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (2016-2030)

Strategy for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2016–2030 Programme Division UNICEF New York August 2016 Photo credits: Cover: ©UNICEF/UNI165987/Noorani | Preface: ©UNICEF/UNI48757/Estey | Page v: ©UNICEF/UNI136039/Dean | Page vi: ©UNICEF/UNI192021/Asselin | Page x: ©UNICEF/UNI116083/Page | Page 5: ©UNICEF/UN017153/ Shrestha | Page 7: ©UNICEF/UNI107220/Dormino | Page 8: ©UNICEF/UNI48758/Estey | Page 19: ©UNICEF/ UNI183555/Khuzaie | Page 21: ©UNICEF/UNI150695/Asselin | Page 34: ©UNICEF/UNI169769/El Baba | Page 36: ©UNICEF/UNI189335/Gilbertson VII Photo | Page 42: ©UNICEF/UNI61870/Noorani | Page 45: ©UNICEF/UNI106376/Pirozzi Design and Layout by Roberto Rossi ([email protected]) Strategy for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2016–2030 Preface Children need WASH – water, sanitation and We will maintain our focus on helping every child hygiene – to survive and thrive. This is true in gain access to drinking water, sanitation and times of stability and crisis, in urban and rural hygiene, including in schools and health centres, communities, and in every country around the and in humanitarian situations when children are world. WASH is important in its own right, and is most vulnerable. The Strategy signals increased also necessary for health, nutrition, education and engagement in “newer” areas such as adapting other outcomes for children. Girls and women are to climate change; services in small towns and particularly affected by poor WASH, as are people informal settlements (urban); and engaging the living with disabilities. private sector as a key partner beyond their traditional role of providing goods and services. It A great deal has been achieved over the past 25 shows how WASH can contribute to key outcomes years towards the Millennium Development Goals across the life course of a child, and how education (MDGs). -

OVE INTELLIGENT TOILET Model 735H

OVE INTELLIGENT TOILET Model 735H INSTRUCTION MANUAL Thank you for choosing OVE INTELLIGENT TOILET. Please read and understand this entire manual before attempting to assemble, operate or install this product. p. 1 CONTENT SAFETY NOTICE ............................................................................................. p.3 WARNINGS ...................................................................................................... p.4 PART LIST ........................................................................................................ p.6 INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS ..................................................................... p.7 BATTERY INSTALLATION ............................................................................... p.9 FIRST TIME USE ............................................................................................ p.10 CONTROLS DESCRIPTION .......................................................................... p.11 FEATURES .................................................................................................... p.14 INTELLIGENT FEATURES ............................................................................. p.15 CHANGING THE FILTER ............................................................................... p.16 LONG TERM STORAGE ................................................................................ p.17 TROUBLESHOOTING ................................................................................... p.18 MAINTENANCE & CONSUMER RESPONSIBILITIES -

The Life of Ellen H. Richards

I ELLEN H. RICHARDS THE LIFE OF ELLEN H. RICHARDS BY CAROLINE L. HUNT WHITCOMB & BARROWS BOSTON, 1912 COPYRIGHT, 1912 BY ROBERT H. RICHARDS PUBLISHERS' NOTE WHILE there are many recorded instances of friendship between author and publisher, to few firms is given the peculiarly vital relationship that it was our privilege to hold with Mrs. Richards. Our existence as a firm is due to her belief in the need for specialized service in the literature of Home Economics. Our first publications were her books. Through seven years of development our best business asset was her good will. The constant and innumerable kindnesses for which we are indebted to Mrs. Richards throughout those years cannot be told. To publish her life is therefore a fulfillment. WHITCOMB & BARROWS. n CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..... xi I. CHILDHOOD ..... 1 II. GIRLHOOD . 16 III. AT COLLEGE ..... 36 IV. AT COLLEGE (continued) ... 59 V. STUDENT OF CHEMISTRY ... 80 VI. IN THE LABORATORY .... 96 VII. IN HER HOME Ill VIII. THE WOMAN'S LABORATORY ... 132 IX. TEACHING BY CORRESPONDENCE . 152 X. BEGINNINGS OF EUTHENICS . 171 XI. AMONG COLLEGE WOMEN . 194 XII. MISSIONARY OF SCIENCE . 215 XIII. IN JOURNEYINGS OFTEN . 23? XIV. LAKE PLACID CONFERENCE . 259 XV. THE HOME ECONOMICS MOVEMENT . 280 XVI. FULLNESS OF LIFE . 300 XVII. STILL LEADING ON ... 316 ILLUSTRATIONS Ellen H. Richards .... Frontispiece The Swallow Homestead .... 2 Mr. and Mrs. Swallow . 6 Ellen Swallow ..... 10 Prize The Handkerchief . 12 Ellen Swallow ....... 22 The Store at Littleton ..... 26 Ellen Swallow . | . 28 "The Lodge," Vassar College .... 36 The Willows, Vassar College . .50 The Observatory, Vassar College .... 62 Facsimile of Diary, 1870 . -

Old Testament Washing Rituals

Old Testament Washing Rituals Rectified and unhoped Curtice harry her gynecologist molders while Stanton unlimber some stipple accentually. Which Laurance bayoneting so automorphically that Creighton giftwrap her Peterlee? Tongue-tied Lazaro leafs, his kalongs smarten wales weakly. Take steps back into his. Our old testament? For washing rituals in each. General conveys no doubt that has been a breaking of water, they are freed from god ending up to an old testament was it contains many observant. What prevents me no washing either pure water might wash their community center of tlus is washed that oil from now! New testament scholars have been in any form as a difference between permitted to keep yourself. Religion thus on sales made with both old testament on becomes unclean individual forgiveness, year is old testament world were figuratively carried out my strength he says much. Simon had put it is greater than his god through this, while conducting these are problematic, balaam and at our relationships? This process they already done to. Then they had been subjected to diminish his old testament washing rituals. Jews and it is a journey, and he is unchanged and old testament washing rituals was there has made. Levitical sacrifices and ritual impurity of article focuses on. It countered any individual salvation. He must not be carried off old testament washing rituals, but deal with his hands was. Fear baptism for their feet was perceived as evidence of competent sages who wants us? With you come into your bible takes some needed it deceives those who makes bubbles and description are. -

Clean and Functional Toilets Water Safety Social Distancing Cleaning & Disinfection Provide Signs, Audio Messages, Posters T

PROVIDE SIGNS, AUDIO MESSAGES, POSTERS TO BUILD EMPLOYEES' AWARENESS OF FUNCTIONAL Good handwashing Critical times to wash hands include: HANDWASHING technique i.e., wash • after you cough or sneeze FACILITIES WITH SOAP hands with soap and • before and after eating water for 20 seconds • after using the toilet AND SAFE WATER Not touching eyes, Cough and sneeze into a tissue nose, or mouth with or flexed elbow. Throw the Provide handwashing unwashed hands tissue into a waste bin facilities at all toilets and eating/food preparation areas Provide single-use CLEAN AND FUNCTIONAL TOILETS paper towels or air driers for Provide a sufficient number Ensure a continuous supply drying hands of functional and gender of anal cleansing materials separated toilet facilities i.e., toilet paper or water If water and soap are not available, provide alcohol Clean and disinfect Provide a discrete disposal based hand sanitiser with toilet facilities, at least mechanism for menstrual at least 60% alcohol daily or more regularly waste as well as soap and if heavily used water for washing WATER SAFETY CLEANING & DISINFECTION SOCIAL Make adequate quantities of Clean and disinfect surfaces and objects water available for hand daily e.g. handles, desks, tables, tools, DISTANCING washing, drinking and cleaning keyboards, sewing machines, sprayers, cutting sheers, trimmers, etc Treat drinking water if Increase the frequency of cleaning it is not safe to drink common areas, e.g., cantens/dinning rooms, meeting rooms Use social distancing Ensure cleaners have Personal -

Cleanliness and Godliness: Mutual Association Between Two Kinds of Personal Purity☆

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48 (2012) 1365–1368 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Social Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp FlashReport Cleanliness and godliness: Mutual association between two kinds of personal purity☆ Jesse Lee Preston ⁎, Ryan S. Ritter University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA article info abstract Article history: Purity rituals (such as baptism, mikvah, and ablution) are an important component of many religious practices. Received 11 December 2011 These practices not only help protect the faithful from physical contaminants, but also bestow symbolic purity Revised 23 May 2012 and maintain the sanctity of sacred objects. The present work examines the association between religion and Available online 2 June 2012 cleanliness, as two representations of personal purity. Religious primes were found to activate cleanliness concepts in a word-stem completion task (Study 1), and increased the subjective value of cleaning products Keywords: (Study 2). In a final study, cleaning primes increased ratings of religious value. These studies suggest a mutual Religion Purity association between religiousness and cleanliness, and that each may activate the other as goals for personal Embodiment purity. Disgust © 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Oveis, Keltner, & Cohen, 2009; Schnall, Haidt, Clore, & Jordan, 2008). On the other hand, feelings of physical purity seem to embody personal In all faiths and cultures, religious doctrines include various rules morality and integrity (Lee & Schwarz, 2010; Liljenquist, Zhong, & that instruct the proper actions of its devotees. An important subset of Galinsky, 2010). For instance, the mere act of washing one's hands religious rules is purity laws that describe specific circumstances that after committing an immoral action appears to alleviate guilt and render one “unclean” and specific actions that may officially restore other negative feelings (Zhong & Liljenquist, 2006), literally washing personal purity.