Cleanliness and Godliness: Mutual Association Between Two Kinds of Personal Purity☆

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting a Person with Washing and Dressing

Factsheet 504LP Supporting a January 2021 person with washing and dressing As a person’s dementia progresses, they will need more help with everyday activities such as washing, bathing and dressing. For most adults, these are personal and private activities, so it can be hard for everyone to adjust to this change. You can support a person with dementia to wash and dress in a way that respects their preferences and their dignity. This factsheet is written for carers. It offers practical tips to help with washing, bathing, dressing and personal grooming. 2 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Contents n How dementia affects washing and dressing — Focusing on the person — Allowing enough time — Making washing and dressing a positive experience — Creating the right environment n Supporting the person with washing and bathing — How to help the person with washing, bathing and showering: tips for carers — Aids and equipment — Skincare and nails — Handwashing and dental care — Washing, drying and styling hair — Hair removal — Using the toilet n Dressing — Helping a person dress and feel comfortable: tips for carers — Shopping for clothes together: tips for carers n Personal grooming — Personal grooming: tips for carers n When a person doesn’t want to change their clothes or wash n Other useful organisations 3 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Supporting a person with washing and dressing How dementia affects washing and dressing The way a person dresses and presents themselves can be an important part of their identity. Getting ready each day is a very personal and private activity – and one where a person may be used to privacy, and making their own decisions. -

A Concept of Clean Toilet from the Islamic Perspective

A CONCEPT OF CLEAN TOILET FROM THE ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVE Asiah Abdul Rahim Department ofArchitecture Kulliyyah afArchitecture and Environmental Design INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA Abstract Islam is the official religion of Malaysia and more than half of the population is Muslim. As Muslims, the aspect of cleanliness is one of the most important and basic things that should be followed and practised in everyday life. Allah loves those cleanse themselves as quoted in the holy Qur'an. .. God loves those who turn to Him, and He loves those who cleanse themselves ". (Surah Al-Baqarah: 222) There is a growing awareness of public toilets among the public and authorities which can be seen in the events such as the "A Clean Toilet Campaign Seminar" held at national level end of July 2003 in lohor Bahru, Johor. Criticisms by visitors and locals stirred the level of consciousness among those responsible directly or indirectly for clean and effective public facilities.Nowadays, toilet is no longer perceived as merely a small and insignificant part of a building. It contributes and serves more than the initial purposes intended. Due to socio-economic changes, a toilet has been diversified and become multi-functions. It has surpassed its traditional role as a place to empty bowels or urinates to serve as comfortable vicinity with conveniences. In developed countries such as Japan and Korea, a public toilet has become a communal area where people could do face washing, showering, freshen up or taking care of their kids and so on. In designing a public toilet, some elements should be highlighted particularly on the understanding of users needs. -

Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel

Core Concepts for Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel 1 Presenter Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control Trinity Health, Livonia, MI Contributions by Heather M. Gilmartin, NP, PhD, CIC Denver VA Medical Center University of Colorado Laraine Washer, MD University of Michigan Health System 2 Learning Objectives • Outline the importance of effective hand hygiene for protection of healthcare personnel and patients • Describe proper hand hygiene techniques, including when various techniques should be used 3 Why is Hand Hygiene Important? • The microbes that cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be transmitted on the hands of healthcare personnel • Hand hygiene is one of the MOST important ways to prevent the spread of infection 1 out of every 25 patients has • Too often healthcare personnel do a healthcare-associated not clean their hands infection – In fact, missed opportunities for hand hygiene can be as high as 50% (Chassin MR, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2015; Yanke E, Am J Infect Control, 2015; Magill SS, N Engl J Med, 2014) 4 Environmental Surfaces Can Look Clean but… • Bacteria can survive for days on patient care equipment and other surfaces like bed rails, IV pumps, etc. • It is important to use hand hygiene after touching these surfaces and at exit, even if you only touched environmental surfaces Boyce JM, Am J Infect Control, 2002; WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, WHO, 2009 5 Hands Make Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Other Microbes Mobile (Image from CDC, Vital Signs: MMWR, 2016) 6 When Should You Clean Your Hands? 1. Before touching a patient 2. -

WASH Pledge: Guiding Principles a Business Commitment to WASH

WASH Pledge: Guiding principles A business commitment to WASH In collaboration with 22 WASHWASH Pledge:Pledge: GuidingGuiding principlesprinciples Contents Foreword | 4 Summary | 5 Introduction | 6 WBCSD Pledge for access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene | 9 Guiding principles | 10 Guidance on water, sanitation and hygiene at the workplace | 13 WASH at the workplace: points of reference for WASH Pledge self-assessment | 13 1. General 13 2. Workplace water supply 14 3. Workplace sanitation 15 4. Workplace hygiene and behavior change 16 5. Value/supply chain WASH 17 6. Community WASH 17 Educational and behavior change activities | 18 WASH across the value chain | 20 WASH Pledge self-assessment tool for business | 24 3 WASH Pledge: Guiding principles Foreword Today, over 785 million people healthier population and increased and quality, within their operations are still without access to safe productivity.3 and across their value chain, in drinking water, another 2.2 billion all global markets. As employers lack safely managed drinking A proposed first step in and members of society, we water services and an estimated accelerating business action is for encourage businesses to 4.2 billion lack access to safely companies to commit to WBCSD’s commit to the Pledge to ensure managed sanitation services.1 Pledge for Access to Safe Water, appropriate access to safe water, This is incompatible not only Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH sanitation and hygiene for their with the World Business Council Pledge). This Pledge aims to have own employees, thus making a for Sustainable Development’s businesses commit to securing direct contribution to addressing (WBCSD) Vision 2050, where nine appropriate access to safe WASH one of the most pressing public billion people are able to live well for all employees in all premises health challenges of our times. -

Clean Your Hands in the Context of Covid-19

WHO SAVE LIVES: CLEAN YOUR HANDS IN THE CONTEXT OF COVID-19 Hand Hygiene in the Community You can play a critical part in fighting COVID-19 • Hands have a crucial role in the transmission of COVID-19. • COVID-19 virus primarily spreads through droplet and contact transmission. Contact transmission means by touching infected people and/or contaminated objects or surfaces. Thus, your hands can spread virus to other surfaces and/or to your mouth, nose or eyes if you touch them. Why is Hand Hygiene so important in preventing infections, including COVID-19? • Hand Hygiene is one of the most effective actions you can take • Community members can play a critical role in fighting COVID-19 to reduce the spread of pathogens and prevent infections, by adopting frequent hand hygiene as part of their day-to-day including the COVID-19 virus. practices. https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/safehands-challengeJoin the #SAFEHANDS challenge now and save lives! Post a video or picture of yourself washing your hands and tag #SAFEHANDS https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/interim-recommendations-on-obligatory-hand-hygiene-against-transmission-of-covid-19WHO calls upon policy makers to provide • the necessary infrastructure to allow people to eectively perform hand hygiene in public places; • to support hand hygiene supplies and best practices in health care facilities. Hand Hygiene in Health Care Why is it important to participate in the WHO global hand hygiene campaign for the fight against COVID-19? • The WHO global hand hygiene campaign SAVEhttps://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/ LIVES: Clean Your Hands mobilizes people around the world to increase adherence to hand hygiene in health care facilities, thus protecting health care workers and patient from COVID-19 and other pathogens. -

The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2000 Coming Clean: The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality April D.J. Garwin University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Garwin, April D.J., "Coming Clean: The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2000. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4240 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by April D.J. Garwin entitled "Coming Clean: The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Michael Logan, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Benita J. Howell, Mariana Ferreira Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To The Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by April D. -

The Mysteries of Purity for Teens

The Mysteries of Purity for Teens FONS VITAE Book 3 The Secret Dimensions of Ritual Purity Praise be to Allah, who has treated His servants gently, for He has called them to serve with cleanliness. The Prophet said: “The religion was based on cleanliness,”……….and he has said,” Ritual Purity is half of the faith.” As understood by those endowed with faculties of discernment, these outward signs indicate that the most important of all matters is the purification of the innermost beings, since it is highly improbable that what is meant by his saying “Ritual purity if half of faith” could be the cultivation of the exterior by cleansing with the pouring and spilling of water, and the devastation of the interior and keeping it loaded with rubbish and filth. How preposterous, how absurd! Purity is central to our faith. So what then is purity? Is it a physical state of the body or is it more? Before we discuss this matter further, let us use the following metaphor. Think of a house that looks very nice from the outside. It has fresh paint, sparkling windows and a nice lawn. At first you might think well of this house. After seeing the inside, however, you realize that this house is actually in poor condition. The foundation is damaged, the wood is rotting and the whole interior is filthy. What is your opinion of the house now that you have seen its interior? Would you want to live in such a house? Of course not! This same rule can be applied to understanding purity in Islam. -

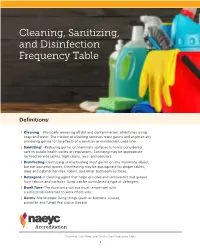

NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), Especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment

Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table Definitions1 › Cleaning2 –Physically removing all dirt and contamination, oftentimes using soap and water. The friction of cleaning removes most germs and exposes any remaining germs to the effects of a sanitizer or disinfectant used later. › Sanitizing3 –Reducing germs on inanimate surfaces to levels considered safe by public health codes or regulations. Sanitizing may be appropriate for food service tables, high chairs, toys, and pacifiers. › Disinfecting–Destroying or inactivating most germs on any inanimate object, but not bacterial spores. Disinfecting may be appropriate for diaper tables, door and cabinet handles, toilets, and other bathroom surfaces. › Detergent–A cleaning agent that helps dissolve and remove dirt and grease from fabrics and surfaces. Soap can be considered a type of detergent. › Dwell Time–The duration a surface must remain wet with a sanitizer/disinfectant to work effectively. › Germs–Microscopic living things (such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi) that cause disease. Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table 1 Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfecting Frequency Table1 Relevant to NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment Before After Daily Areas each each (End of Weekly Monthly Comments4 Use Use the Day) Food Areas Clean, Clean, Food preparation Use a sanitizer safe for and then and then surfaces food contact Sanitize Sanitize If washing the dishes and utensils by hand, Clean, use a sanitizer safe -

Euthenics, There Has Not Been As Comprehensive an Analysis of the Direct Connections Between Domestic Science and Eugenics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics Caleb J. true University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons true, Caleb J., "Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 730. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/730 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented by CALEB J. TRUE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2011 History © Copyright by Caleb J. True 2011 All Rights Reserved EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented By Caleb J. True Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________ Laura L. Lovett, Chair _______________________________ Larry Owens, Member _______________________________ Kathy J. Cooke, Member ________________________________ Joye Bowman, Chair, History Department DEDICATION To Kristina. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Laura L. Lovett, for being a staunch supporter of my project, a wonderful mentor and a source of inspiration and encouragement throughout my time in the M.A. -

The Habitus of Hygiene: Discourses of Cleanliness and Infection Control In

Hygiene as Habitus: Putting Bourdieu to Work in Hospital Infection Control Brian Brown and Nelya Koteyko 1. Introduction This chapter takes as its starting point accounts of nurse managers and infection control staff as they talk about their working lives and how they try to implement practices which are believed to enhance safety in relation to healthcare acquired infections. The control of infection, particularly MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), in hospital work is a contentious issue that attracts a good deal of publicity in the UK and efforts to control it have exercised policymakers, managers, infection control staff and other health care practitioners over the last several years. In mid 2007 UK newspapers presented headlines such as „Shame of the filthy wards‟ (Daily Mail 18/6/2007), prompted by the release of Healthcare Commission data to the effect that 99 out of 384 hospital trusts in England were not in compliance with the UK‟s hygiene code (Healthcare Commission 2007). Gordon Brown commenced his premiership with a commitment among other things to reduce rates of infection in hospitals, seeking to halve the number of people diagnosed with MRSA by April 2008 (Revill 2007). As Revill goes on to report, 300,000 people a year are currently diagnosed with a hospital acquired infection. Reports have also surfaced in the UK news media concerning the growing proportion of death certificates issued which mentioned MRSA or another important healthcare acquired infection, clostridium difficile (Waterfield and Fleming 2007). In press reports, and arguably in public opinion too, a link is made between the specific microbes and the general state of cleanliness in hospital accommodation. -

Bathing and Grooming Poultry

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Bathing and Grooming Poultry When showing poultry, whether for exhibition or in showmanship, the condition and cleanliness of the birds are reflections of their owners. Designate an area for your show birds, and do not allow them to run with the rest of the flock. If possible, keep them in individual coops or cages during the show season to maintain condition and cleanliness. Bathing Birds should be bathed at least five days before a show. This allows the bird time to dry completely, oil to be restored to the feathers, and for them to groom their own feathers. Before you begin, gather the necessary items needed to bathe your birds. List of Bathing Supplies • Toothbrush – used to scrub the shanks, feet, toes, and toenails • Apple Cider Vinegar – used to help rinse the shampoo out of the feathers. Use about ½ cup for a tub of water • Shampoo – used to clean the feathers; do not use a harsh shampoo as it will make the feathers brittle. You can use a flea and tick shampoo recommended for cats or dogs, which not only cleans the birds but kills lice or mites gone unnoticed. • Blow Dryer – used to dry loose-feathered birds if needed • Towels – used to dry birds • Nail clippers and file – Used to clip toenails and upper beak, and file the beak • Sponge – used to wash the birds, particularly the head • Cotton balls and styptic powder – to stop bleeding in case the nails and beak are cut too short • Three tubs or 5-gallon buckets of warm water– to bathe and rinse birds; Note: You can use a utility tub with warm running water located in your basement, work room, etc., to wash and rinse your chickens instead of the three tubs. -

Halal GUIDELINES for the PREPARATION

Guidelines For The Preparation Of HALAL Foods. GUIDELINES FOR THE PREPARATION OF HALAL FOODS Prepare By: UHF Certification Council (HALAL CERTIFICATION BODY) Halal World (Halal certification authority in Nepal) Head Office: Chandragiri-10, Kathmandu, Nepal City Office: Sanepal, Lalitpur , Nepal. E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] www.halalnepal.com | www.uhfcertification.org [DOC VER – 1.1 Dtd 2013; Rev Ver 1.3 Dtd 2016] UHF Certification Council/(Halal World) Guidelines For The Preparation Of HALAL Foods. INTRODUCTION The processors of foods and goods for the Muslim market need to understand and comply with the specific requirements of the Muslim consumers before their product could be labeled as HALAL food in Nepal. The use of the word “HALAL” (Permissible), ‘CERTIFIED HALAL’, ‘FOODS FOR MUSLIM’ and other similar labeling will only be granted if all requirement is met. The consumption of Halal foods and goods is compulsory to all Muslims. Lack of knowledge, awareness and understanding of the Halal concept among Muslims and the manufacturers of Halal products may cause the loss of appreciation to Halal. In fact the holy Quran addressed all human being and not just Muslim to search for Halal and it is for their own benefit. One should understand that Halal food requires that it is prepared in the most hygienic manner meeting international food safety standards and should not be viewed as offensive to any religious belief. The basic issue in Halal food production is cleanliness, free from ‘contamination’ and healthy food as defined in the Quran. Thus, these guidelines are prepared to interpret and explain, to the processors and the public, either Muslim or non-Muslim, the Halal and Haram (Non-Permissible) aspects as stipulated in Islamic laws.