Forestry in Karnataka a Journey of 150 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) from Kali River, Karnataka Region of Western Ghats, Peninsular India

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (December 2016), 3(4): 266–274 Received: August 14, 2016 © 2016 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: November 28, 2016 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2016. http://www.ijichthyol.org Description of a new species of large barb of the genus Hypselobarbus (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) from Kali River, Karnataka region of Western Ghats, peninsular India Muthukumarasamy ARUNACHALAM*1, Sivadoss CHINNARAJA2, Paramasivan SIVAKUMAR2, Richard L. MAYDEN3 1Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Sri Paramakalyani Centre for Environmental Sciences, Alwarkurichi–627 412, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Research Department of Zoology, Poompuhar College (Autonomous), Melaiyur-609 107, Sirkali, Nagapattinam dist., Tamil Nadu, India. 3Department of Biology, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, Missouri 63103, USA. * Email: [email protected] Abstract: A new cyprinid fish, Hypselobarbus kushavali, is described from Kali River, Karnataka, India. Hypselobarbus kushavali is diagnosed from its closest congener, H. dobsoni, by having more upper transverse scale rows, more circumferential scale rows and more lateral line to pelvic scale rows, and from H. bicolor and H. jerdoni by having fewer lateral-line and fewer circumpeduncular scale rows. Diagnostic features for H. kushavali are also provided relative to other species of the genus. Keywords: Cyprinidae, Hypselobarbus kushavali, Distribution, Taxonomy. Zoobank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:680F325A-0131-47D5-AFD0-E83F7C3D74C3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:C06CDB6B-0969-4D7B-9478-A9E1395596CB Citation: Arunachalam, M.; Chinnaraja, S.; Sivakumar P. & Mayden, R.L. 2016. Description of a new species of large barb of the genus Hypselobarbus (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) from Kali River, Karnataka region of Western Ghats, peninsular India. Iranian Journal of Ichthyology 3(4): 266-274. -

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. Sri. Chandrashekhar Mrutyunjaya Joshi PRL

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. Sri. Chandrashekhar Mrutyunjaya Joshi PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 22-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 11.00 AM-02.00 PM 1 Crl.Misc. 1405/2020 Gurusidda Shanker Chandaragi Patil A.R. (HEARING) Age 39yrs R/o yattinkeri Tq Kittur Dt Belagavi Vs The State of Karnataka R/by P.P. Belagavi 2 Crl.Misc. 596/2020 Kasimsab Sultansab Nadaf Age. V.S.Karajagi (NOTICE) 33 years R/o Sankeshwar ,Tal. Hukkeri, Belagavi. Vs Salma W/o Kasimsab Nadaf Age. 31 years R/o M.G Colony, Bailhongal, Belagavi. 3 SC 102/2017 State of Karnataka R/by PP SPL.PP (EVIDENCE) Belagavi. Vs Najim Nilawar @ Mahammad Najim Nilawar age 51yrs R/o Bandar Road Batkal Dt Uttar Kannada. 4 SC 141/2019 The State of Karnataka R/by PP, PP (F.D.T.) Belagavi. Vs I Y Chobri Kareppa Basappa Nayik Age. 33 years R/o Budraynoor,Tal.Belagavi. 5 SC 380/2019 The State of Karnataka PP (HBC) Vs Bharmappa alias Bharma Chandru Kurabagatti age 20 yrs R/o Sahyadri colony Jaitun Mal Udyambhag BGV 6 SC 47/2020 The State of Karnataka R/by PP, PP (ISSUE NBW TO Belagavi. ACCUSED) Vs Raj Shravan Londe Age. 21 years R/o Gyangawadi, Shivabasav Nagar, Belagavi. 7 Crl.Misc. 1442/2020 Vaibhav Rajendra Patil Age Shaikh M.M. (OBJECTION) 29yrs R/o Sai Anand Bungalow Sant Gnyaneshwar Nagar, Majagaon Belagavi Vs The State of Karnataka R/by Public Prosecutor Belagavi. 8 Crl.Misc. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E.1 Introduction the Government Of

Consultancy Services for Four Laning of existing DRAFT FEASIBILITY REPORT Goa/Karnataka Border-Panaji Goa Section of NH-4A from Km 84.000 to Km 153.075 in the state of Goa on BOT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Toll) basis under NHDP-III (Anmod to Panaji Section) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E.1 Introduction The Government of India has envisaged to create a world-class infrastructure facility, to boost the economic development in the country, for which National Highways Au- thority of India (NHAI) plays key role. NHAI has been entrusted to implement the de- velopment of some of the stretches of National Highways under National Highway Development Programme on EPC/BOT basis. As part of this endeavor, the Public Works Department (PWD) of Government of Goa has decided for the development of existing Goa/Karnataka Border- Panaji Goa Section of NH-4A from Km 84/000 to 153/075 on BOT (Toll) basis under NHDP-III (Anmod to Panaji section) to four Lane configuration. Public Works Department (PWD) of Goa has appointed M/s Aarvee Associates Archi- tects Engineers & Consultants Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad to provide consultancy services for detailed engineering study for the above road section. The project stretch excludes following reaches: 1. From Km 118 (Kandepar) to Km 125 (Safa Maszid) 2. From Km 143.400(Ella) to Km 153.075 (Panaji). E.2 Project Description The Project Highway is a section of NH-4A(Belgaum-Anmod-Ponda-Panaji) between Anmod and Panaji, passing through villages Molem, Sangod, Dharbandora, Piliem, Tiska, Candepar, Curti, Ambegal, Veling, Boma, Banastarim, Corlim, Velha goa, Ribandar. The entire stretch of NH-4A lies in the states of Karnataka and Goa. -

THE NILGIRIS Kms from Ooty and Kotagiri 31 Kms from Ooty, Are the Three Hill Stations of This District

THE NILGIRIS kms from Ooty and Kotagiri 31 kms from Ooty, are the three hill stations of this district. Geographical Location • The Nilgiris is situated at an elevation of 900 to 2636 meters above MSL. • The Nilgiris is bounded on North by Karnataka State on the East by Coimbatore District, Erode District, South by Coimbatore District and Kerala State and as the West by Kerala State. Important places District Collector: Tmt. J. Innocent Divya • Doddabetta - 2,623 mts above MSL - I.A.S highest Peak in the Tamil Nadu. • The Nilgiri Mountain Train-One among the three Mountain Railways of India designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Three railways, the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, the Nilgiri Mountain Railway, and the Kalka– Shimla Railway, are collectively designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name Mountain Railways of India. The fourth railway, the Matheran Hill Railway, is on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. REVENUE DIVISIONS: • Mudumalai National Park UDHAGAI • Pykara Waterfalls and the Ooty Lake COONOOR • Botanical Garden – Ooty GUDALUR • Rose Garden - Ooty HISTORY: • Ooty Lake and Boat House • The Name ‘Nilgiris’ means Blue hills the first mention of this name has been found • Raj Bhavan - Ooty in the Silappadikaram. • Dolphin's Nose - Coonoor • One of the oldest mountain ranges, located at the tri-junction of Tamil Nadu, Kerala • Lamb's rock - Coonoor and Karnataka. • Glenmorgan - Ooty • Nilgiris is a part of the Western Ghats. Ooty the “Queen of Hill Stations”, Coonoor 19 • Avalanche - Ooty For any queries mail to: [email protected] Forest • South Western ghats - Nilgiri tahrs are found only in the montane grasslands of the Southwestern Ghats. -

Dwd Pryamvacancy.Pdf

DIST_NAME TALUK_NAME SCH_COD SCH_NAM SCH_ADR DESIG_NAME SUBJECT.SUBJECT TOT_VAC BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020107302 GOVT KBLPS INGALAGUNDI KALAS Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020106104 GOVT UBHPS JALAGERI JALAGERI Assistant Master ( AM ) URDU - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020101301 GOVT HPS BANKANERI BANKANERI Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020100702 GOVT KGS ANAWAL ANAWAL Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020100401 GOVT HPS ALUR SK ALUR SK Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 2 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020111503 GOVT HPS NARENUR LT 2 NARENUR Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020111306 UGLPS NANDIKESHWAR NANDIKESHWAR Assistant Master ( AM ) URDU - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020117602 GOVT UBKS NO 3, GULEDGUDD GULEDGUDD WARD 6 Assistant Master ( AM ) URDU - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020102902 GOVT HPS FAKIRBUDIHAL FAKIR BUDIHAL Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020109402 GOVT LBS KUTAKANAKERI KUTAKANKERI Assistant Master ( AM ) URDU - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020110901 GOVT HPS MUSTIGERI MUSTIGERI Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 2 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020114302 GOVT UBS YANDIGERI YENDIGERI Assistant Master ( AM ) URDU - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020101801 GOVT HPS BEERANOOR BEERANOOR Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020107701 GOVT HPS KARALKOPPA H KARALKOPPA Assistant Master ( AM ) KANNADA - GENERAL 1 BAGALKOT BADAMI 29020107602 GOVT HPS KARADIGUDD SN KARADIGUDDA -

Public Interest Litigation

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU (ORIGINAL JURISDICTION) WRIT PETITION NO. OF 2019(GM-RES)PIL Between 1. Suresh Heblikar, Aged 69, son of Sri Balakrishna ,403, 18th Cross, 3rd Block, Jayanagar, Bengaluru 560011 2. Joseph Hoover, Aged 58 years, son of James Hoover S/o #116, God’s Gift, 2nd Cross, 4th Main, Giridhama Layout, Rajarajeswari Nagar, Petitioners Bengaluru 560098 3. J Manjunath , Aged 60 years ,son of. B.V.JanakiramNaidu, 566, 21st Main, 36th Cross, 4 T Block, Jayanagar, Bengaluru 560041 And 1. Union of India by its Deputy Inspector General Of Forest(WL) Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change,6th Floor, VayuWing,IndiraParyavaranBhavan, Jor Bag Road,Aliganj NEW DELHI-110 003 Respondents 2. Principal Chief Conservator of Forests , AranyaBhavan, Bengaluru-560 003, 3 National Highways Authority of India By its Assistant Commissioner, Belagavi And CALA,NH4-A, BELAGAVI- MEMORANDUM OF WRIT PETITION UNDER ARTICLES 226 AND 227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA The Petitioners in the above matter seeks leave of this Hon’ble Court to file the Petition as Public Interest Litigation. The Petitioners have no personal or vested interest in the matter. 1. Petitioner No.1, Mr. Suresh Heblikar, aged 69 Years, belongs to Dharwad, a place known for arts, culture, poets and writers. He has nearly twenty years of experience in Films and Environment. He is also a powerful environmental voice in regional T.V channels representing environmental issues. He is a recipient of several awards like the Rajiv Gandhi Environment Award, Citizen Extraordinaire Award, United Nations – OSIRIS F.A.O Award to name a few from Govt of Karnataka, Rotary International and 19th Agro film festival 2002, Nitra, Slovakia. -

Southern India Project Elephant Evaluation Report

SOUTHERN INDIA PROJECT ELEPHANT EVALUATION REPORT Mr. Arin Ghosh and Dr. N. Baskaran Technical Inputs: Dr. R. Sukumar Asian Nature Conservation Foundation INNOVATION CENTRE, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, BANGALORE 560012, INDIA 27 AUGUST 2007 CONTENTS Page No. CHAPTER I - PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA -------------------------------------01 CHAPTER II - PROJECT ELEPHANT KARNATAKA -------------------------------------------------------06 CHAPTER III - PROJECT ELEPHANT KERALA -------------------------------------------------------15 CHAPTER IV - PROJECT ELEPHANT TAMIL NADU -------------------------------------------------------24 CHAPTER V - OVERALL CONCLUSIONS & OBSERVATIONS -------------------------------------------------------32 CHAPTER - I PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA A. Objectives of the scheme: Project Elephant was launched in February 1992 with the following major objectives: 1. To ensure long-term survival of the identified large elephant populations; the first phase target, to protect habitats and existing ranges. 2. Link up fragmented portions of the habitat by establishing corridors or protecting existing corridors under threat. 3. Improve habitat quality through ecosystem restoration and range protection and 4. Attend to socio-economic problems of the fringe populations including animal-human conflicts. Eleven viable elephant habitats (now designated Project Elephant Ranges) were identified across the country. The estimated wild population of elephants is 30,000+ in the country, of which a significant -

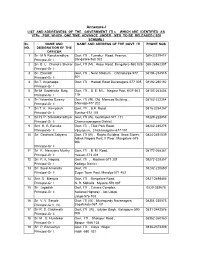

Annexure-I LIST and ADDRESSESS of the GOVERNMENT ITI S WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS Vtps for WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES to BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL

Annexure-I LIST AND ADDRESSESS OF THE GOVERNMENT ITI s WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS VTPs FOR WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES TO BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL. NAME AND NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE GOVT. ITI PHONE NOS NO. DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICER 1 Sri M N Renukaradhya Govt. ITI , Tumakur Road, Peenya, 080-23379417 Principal-Gr I Bangalore-560 022 2 Sri B. L. Chandra Shekar Govt. ITI (M) , Hosur Road, Bangalore-560 029 080-26562307 Principal-Gr I 3 Sri Ekanath Govt. ITI , Near Stadium , Chitradurga-577 08194-234515 Principal-Gr II 501 4 Sri T. Anjanappa Govt. ITI , Hadadi Road Davanagere-577 005 08192-260192 Principal-Gr I 5 Sri M Sadathulla Baig Govt. ITI , B. E. M.L. Nagara Post, KGF-563 08153-263404 Principal-Gr I 115 6 Sri Yekantha Swamy Govt. ITI (W), Old Momcos Building, , 08182-222254 Principal-Gr II Shimoga-577 202 7 Sri T. K. Kempaiah Govt. ITI , B.H. Road, 0816-2254257 Principal-Gr II Tumkur-572 101 8 Sri H. P. Srikanataradhya Govt. ITI (W), Gundlupet-571 111 08229-222853 Principal-Gr II Chamarajanagara District 9 Smt K. R. Renuka Govt. ITI , Tilak Park Road, 08262-235275 Principal-Gr II Vijayapura, Chickamagalur-577 101 10 Sri Giridhara Saliyana Govt. ITI (W) , Raghu Building Urwa Stores, 0824-2451539 Ashok Nagara Post, II Floor, Mangalore-575 006. Principal-Gr II 11 Sri K. Narayana Murthy Govt. ITI , B. M. Road, 08172-268361 Principal-Gr II Hassan-573 201 12 Sri P. K. Nagaraj Govt. ITI , Madikeri-571 201 08272-228357 Principal-Gr I Kodagu District 13 Sri Syed Amanulla Govt. -

Download Full Report

PREFACE This Report for the year ended 31 March 2009 has been prepared for submission to the Governor under Article 151 (2) of the Constitution. The audit of revenue receipts of the State Government is conducted under Section 16 of the Comptroller and Auditor General's (Duties, Powers and Conditions of Service) Act, 1971. This Report presents the results of audit of receipts comprising sales tax, state excise, taxes on motor vehicles, land revenue, stamps and registration fees, other tax receipts and non-tax receipts of the State. The cases mentioned in the Report are among those which came to notice in the course of test audit of records during the year 2008-09 as well as those which came to notice in earlier years but could not be included in previous years’ Reports. iii OVERVIEW This Report contains 26 paragraphs including three reviews pointing out non-levy or short levy of tax, interest, penalty, revenue forgone, etc., involving Rs. 336.61 crore. Some of the major findings are mentioned below: I General Total revenue receipts of the State Government for the year 2008-09 amounted to Rs. 43,290.67 crore against Rs. 41,151.14 crore for the previous year. 71 per cent of this was raised by State through tax revenue (Rs. 27,645.66 crore) and non-tax revenue (Rs. 3,158.99 crore). The balance 29 per cent was received from the Government of India as State’s share of divisible Union taxes (Rs. 7,153.77 crore) and grants-in-aid (Rs. 5,332.25 crore). -

Tamil Nadu 2014

ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE DEMAND No. 54 FORESTS 2014-2015 M.S.M. ANANDAN MINISTER FOR FORESTS © GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU 2014 DEMAND No.54 POLICY NOTE 2014-2015 FOREST DEPARTMENT INTRODUCTION "kâÚU« k©Q« kiyÍ« mâãH‰ fhL« cilaJ mu©" - ÂU¡FwŸ (742) "A fort is that which owns fount of waters crystal clear, an open space, a hill, and shade of beauteous forest near." - Thirukkural (742) The ancient Tamil poets have emphasized the importance of dense forests, clean water and fertile soil in providing ecological security to the mankind. Forests are a complex eco-system which play a dual role of a renewable resource and also as a vital support base for safeguarding the overall environment and ecological balance. It is forest cover that has preserved the soil and its heavy humus that has acted as a porous reservoir to 1 retain water and is gradually releasing it in a sustained flow over a period of time. Trees draw water from the earth crust and release it to the atmosphere by process of transpiration as a part of water cycle. Trees also purify the air by releasing oxygen into the atmosphere after consuming carbon-di-oxide during photosynthesis. The survival and well-being of any nation depends on sustainable social and economic progress, which satisfies the needs of the present generation without compromising the interest of future generation. Spiraling population and increasing industrialization have posed a serious challenge to the preservation of our terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Overexploitation of our resources due to rapid population growth has lead to degradation of forests and denudation of agricultural lands. -

Educational Profile of Karnataka

Educational Profile of Karnataka : As of March 2013, Karnataka had 60036 elementary schools with 313008 teachers and 8.39 million students, and 14195 secondary schools with 114350 teachers and 2.09 million students. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnataka - cite_note-school-99 There are three kinds of schools in the state, viz., government-run, private aided (financial aid is provided by the government) and private unaided (no financial aid is provided). The primary languages of instruction in most schools are Kannada apart from English, Urdu and Other languages. The syllabus taught in the schools is by and large the state syllabus (SSLC) defined by the Department of Public Instruction of the Government of Karnataka, and the CBSE, ICSE in case of certain private unaided and KV schools. In order to provide supplementary nutrition and maximize attendance in schools, the Karnataka Government has launched a mid-day meal scheme in government and aided schools in which free lunch is provided to the students. A pair of uniforms and all text books is given to children; free bicycles are given to 8th standard children. Statewide board examinations are conducted at the end of the period of X standard and students who qualify are allowed to pursue a two-year pre-university course; after which students become eligible to pursue under-graduate degrees. There are two separate Boards of Examination for class X and class XII. There are 652 degree colleges (March 2011) affiliated with one of the universities in the state, viz. Bangalore University, Gulbarga University, Karnataka University, Kuvempu University, Mangalore University and University of Mysore .