Heavy Metal Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultura Do Software E Autonomização Da Game Music∗

Cultura do software e autonomização da game music∗ Camila Schäfery Tiago Ricciardi Correa Lopesz Índice Nesse cenário, presenciamos novas formas de produção, distribuição e consumo de pro- Introdução1 dutos culturais cujos efeitos se fazem sentir 1 Os sons nos jogos digitais3 em todo o meio ambiente midiático. As- 2 Cultura do software e game music 4 sim sendo, o presente artigo analisa a au- Conclusão 11 tonomização da game music, ou música de Referências bibliográficas 11 videogame, como processo resultante de um conjunto de práticas operadas no interior da cultura que encontram nos softwares as bases Resumo de sua realização. Palavras-chave: game music; jogos Vivemos hoje a cultura do software, uma eletrônicos; cultura do software. etapa do nosso desenvolvimento civilizatório na qual os programas computacionais for- mam camadas tecnoculturais que cobrem to- das as áreas da sociedade contemporânea. Introdução ∗Artigo originalmente publicado e apresentado ao CLUHAN (1969) já dizia em O meio eixo temático “Jogos, Redes Sociais, Mobilidade e M são as massagens que o surgimento Estruturas Comunicacionais Urbanas”, do V Simpó- e assimilação de novas tecnologias de co- sio Nacional da ABCiber, ocorrido em novembro de 2011, em Florianópolis (SC). municação afetam não somente o segmento yGraduada em Jornalismo (UNISINOS), midiático ao qual se destinam (por exemplo, criadora do blog Console Sonoro (http: o surgimento dos videocassetes e das fitas //consolesonoro.blogspot.com) e colu- VHS em relação ao cinema e à televisão), http://pontov.com.br/ -

Elena Is Not What I Body and Remove Toxins

VISIT HTTP://SPARTANDAILY.COM VIDEO SPORTS Hi: 68o A WEEKEND SPARTANS HOLD STROLL Lo: 43o ALONG THE ON TO CLOSE WIN OVER DONS GUADALUPE Tuesday RIVER PAGE 10 February 3, 2015 Volume 144 • Issue 4 Serving San Jose State University since 1934 LOCAL NEWS Electronic duo amps up Philz Coff ee Disney opens doors for SJSU design team BY VANESSA GONGORA @_princessness_ Disney continues to make dreams come true for future designers. Four students from San Jose State University were chosen by Walt Disney Imagineering as one of the top six college teams of its 24th Imaginations Design Competition. The top six fi nal teams were awarded a fi ve-day, all-expense-paid trip to Glendale, Calif., from Jan. 26–30, where they presented their projects to Imag- ineering executives and took part in an awards cere- mony on Jan. 30. According to the press release from Walt Disney Imagineering, the competition was created and spon- sored by Walt Disney Imagineering with the purpose of seeking out and nurturing the next generation of diverse Imagineers. This year’s Imaginations Design Competition consisted of students from American universities and Samson So | Spartan Daily colleges taking what Disney does best today and ap- Gavin Neves, one-half of the San Jose electronic duo “Hexes” performs “Witchhunt” at Philz plying it to transportation within a well-known city. Coffee’s weekly open mic night on Monday, Feb. 2. Open mic nights take place every Monday at The team’s Disney transportation creation needed the coffee shop from 6:30 p.m. to 9:15 p.m. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Spartan Daily, Febuary 3, 2015

VISIT HTTP://SPARTANDAILY.COM VIDEO SPORTS Hi: 68o A WEEKEND SPARTANS HOLD STROLL Lo: 43o ALONG THE ON TO CLOSE WIN OVER DONS GUADALUPE Tuesday RIVER PAGE 10 February 3, 2015 Volume 144 • Issue 4 Serving San Jose State University since 1934 LOCAL NEWS Electronic duo amps up Philz Coff ee Disney opens doors for SJSU design team BY VANESSA GONGORA @_princessness_ Disney continues to make dreams come true for future designers. Four students from San Jose State University were chosen by Walt Disney Imagineering as one of the top six college teams of its 24th Imaginations Design Competition. The top six fi nal teams were awarded a fi ve-day, all-expense-paid trip to Glendale, Calif., from Jan. 26–30, where they presented their projects to Imag- ineering executives and took part in an awards cere- mony on Jan. 30. According to the press release from Walt Disney Imagineering, the competition was created and spon- sored by Walt Disney Imagineering with the purpose of seeking out and nurturing the next generation of diverse Imagineers. This year’s Imaginations Design Competition consisted of students from American universities and Samson So | Spartan Daily colleges taking what Disney does best today and ap- Gavin Neves, one-half of the San Jose electronic duo “Hexes” performs “Witchhunt” at Philz plying it to transportation within a well-known city. Coffee’s weekly open mic night on Monday, Feb. 2. Open mic nights take place every Monday at The team’s Disney transportation creation needed the coffee shop from 6:30 p.m. to 9:15 p.m. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

3 Ninjas Kick Back 688 Attack Sub 6-Pak Aaahh!!! Real

3 NINJAS KICK BACK 688 ATTACK SUB 6-PAK AAAHH!!! REAL MONSTERS ACTION 52 ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES THE ADDAMS FAMILY ADVANCED BUSTERHAWK GLEYLANCER ADVANCED DAISENRYAKU - DEUTSCH DENGEKI SAKUSEN THE ADVENTURES OF BATMAN & ROBIN THE ADVENTURES OF MIGHTY MAX THE ADVENTURES OF ROCKY AND BULLWINKLE AND FRIENDS AERO THE ACRO-BAT AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 AEROBIZ AEROBIZ SUPERSONIC AFTER BURNER II AIR BUSTER AIR DIVER ALADDIN ALADDIN II ALEX KIDD IN THE ENCHANTED CASTLE ALIEN 3 ALIEN SOLDIER ALIEN STORM ALISIA DRAGOON ALTERED BEAST AMERICAN GLADIATORS ANDRE AGASSI TENNIS ANIMANIACS THE AQUATIC GAMES STARRING JAMES POND AND THE AQUABATS ARCADE CLASSICS ARCH RIVALS - THE ARCADE GAME ARCUS ODYSSEY ARIEL THE LITTLE MERMAID ARNOLD PALMER TOURNAMENT GOLF ARROW FLASH ART ALIVE ART OF FIGHTING ASTERIX AND THE GREAT RESCUE ASTERIX AND THE POWER OF THE GODS ATOMIC ROBO-KID ATOMIC RUNNER ATP TOUR CHAMPIONSHIP TENNIS AUSTRALIAN RUGBY LEAGUE AWESOME POSSUM... ...KICKS DR. MACHINO'S BUTT AYRTON SENNA'S SUPER MONACO GP II B.O.B. BABY BOOM (PROTO) BABY'S DAY OUT (PROTO) BACK TO THE FUTURE PART III BALL JACKS BALLZ 3D - FIGHTING AT ITS BALLZIEST ~ BALLZ 3D - THE BATTLE OF THE BALLZ BARBIE SUPER MODEL BARBIE VACATION ADVENTURE (PROTO) BARE KNUCKLE - IKARI NO TETSUKEN ~ STREETS OF RAGE BARE KNUCKLE III BARKLEY SHUT UP AND JAM 2 BARKLEY SHUT UP AND JAM! BARNEY'S HIDE & SEEK GAME BARVER BATTLE SAGA - TAI KONG ZHAN SHI BASS MASTERS CLASSIC - PRO EDITION BASS MASTERS CLASSIC BATMAN - REVENGE OF THE JOKER BATMAN - THE VIDEO GAME BATMAN FOREVER BATMAN RETURNS BATTLE GOLFER YUI -

5794 Games.Numbers

Table 1 Nintendo Super Nintendo Sega Genesis/ Master System Entertainment Sega 32X (33 Sega SG-1000 (68 Entertainment TurboGrafx-16/PC MAME Arcade (2959 Games) Mega Drive (782 (281 Games) System/NES (791 Games) Games) System/SNES (786 Engine (94 Games) Games) Games) Games) After Burner Ace of Aces 3 Ninjas Kick Back 10-Yard Fight (USA, Complete ~ After 2020 Super 005 1942 1942 Bank Panic (Japan) Aero Blasters (USA) (Europe) (USA) Europe) Burner (Japan, Baseball (USA) USA) Action Fighter Amazing Spider- Black Onyx, The 3 Ninjas Kick Back 1000 Miglia: Great 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) 6-Pak (USA) 1942 (Japan, USA) Man, The - Web of Air Zonk (USA) 1 on 1 Government (Japan) (USA) 1000 Miles Rally (World, set 1) (v1.2) Fire (USA) 1941: Counter 1943 Kai: Midway Addams Family, 688 Attack Sub 1943 - The Battle of 7th Saga, The 18 Holes Pro Golf BC Racers (USA) Bomb Jack (Japan) Alien Crush (USA) Attack Kaisen The (Europe) (USA, Europe) Midway (USA) (USA) 90 Minutes - 1943: The Battle of 1944: The Loop 3 Ninjas Kick Back 3-D WorldRunner Borderline (Japan, 1943mii Aerial Assault (USA) Blackthorne (USA) European Prime Ballistix (USA) Midway Master (USA) (USA) Europe) Goal (Europe) 19XX: The War Brutal Unleashed - 2 On 2 Open Ice A.S.P. - Air Strike 1945k III Against Destiny After Burner (World) 6-Pak (USA) 720 Degrees (USA) Above the Claw Castle, The (Japan) Battle Royale (USA) Challenge Patrol (USA) (USA 951207) (USA) Chaotix ~ 688 Attack Sub Chack'n Pop Aaahh!!! Real Blazing Lazers 3 Count Bout / Fire 39 in 1 MAME Air Rescue (Europe) 8 Eyes (USA) Knuckles' Chaotix 2020 Super Baseball (USA, Europe) (Japan) Monsters (USA) (USA) Suplex bootleg (Japan, USA) Abadox - The Cyber Brawl ~ AAAHH!!! Real Champion Baseball ABC Monday Night 3ds 4 En Raya 4 Fun in 1 Aladdin (Europe) Deadly Inner War Cosmic Carnage Bloody Wolf (USA) Monsters (USA) (Japan) Football (USA) (USA) (Japan, USA) 64th. -

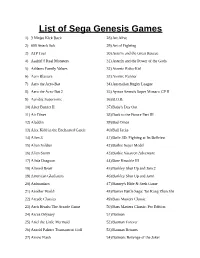

List of Sega Genesis Games

List of Sega Genesis Games 1) 3 Ninjas Kick Back 28) Art Alive 2) 688 Attack Sub 29) Art of Fighting 3) ATP Tour 30) Asterix and the Great Rescue 4) Aaahh!!! Real Monsters 31) Asterix and the Power of the Gods 5) Addams Family Values 32) Atomic Robo-Kid 6) Aero Blasters 33) Atomic Runner 7) Aero the Acro-Bat 34) Australian Rugby League 8) Aero the Acro-Bat 2 35) Ayrton Senna's Super Monaco GP II 9) Aerobiz Supersonic 36) B.O.B. 10) After Burner II 37) Baby's Day Out 11) Air Diver 38) Back to the Future Part III 12) Aladdin 39) Bad Omen 13) Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle 40) Ball Jacks 14) Alien 3 41) Ballz 3D: Fighting at Its Ballziest 15) Alien Soldier 42) Barbie Super Model 16) Alien Storm 43) Barbie Vacation Adventure 17) Alisia Dragoon 44) Bare Knuckle III 18) Altered Beast 45) Barkley Shut Up and Jam 2 19) American Gladiators 46) Barkley Shut Up and Jam! 20) Animaniacs 47) Barney's Hide & Seek Game 21) Another World 48) Barver Battle Saga: Tai Kong Zhan Shi 22) Arcade Classics 49) Bass Masters Classic 23) Arch Rivals: The Arcade Game 50) Bass Masters Classic: Pro Edition 24) Arcus Odyssey 51) Batman 25) Ariel the Little Mermaid 52) Batman Forever 26) Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf 53) Batman Returns 27) Arrow Flash 54) Batman: Revenge of the Joker 55) Battle Mania 84) Bubble and Squeak 56) Battle Squadron 85) Bubsy II 57) BattleTech: A Game of Armored Combat 86) Bubsy in: Claws Encounters of the Furred Kind 58) Battletoads 87) Buck Rogers: Countdown to Doomsday 59) Battletoads-Double Dragon 88) Bugs Bunny in Double Trouble 60) -

Unfolding Stereo Audio for High- Density Loudspeaker Arrays

Auragami Unfolding Stereo Audio for High- Density Loudspeaker Arrays John Tanner Upthegrove 14 May 2019 Auragami: Unfolding Stereo Audio for High-Density Loudspeaker Arrays John Tanner Upthegrove Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Theatre Arts Randy Ward Charles Nichols Chris Russo May 14th, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: spatial audio, 3-D sound, ambisonics, sound design, digital audio, signal processing ©John Tanner Upthegrove CC BY https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ii Auragami: Unfolding Stereo Audio for High-Density Loudspeaker Arrays John Tanner Upthegrove ABSTRACT As a critical complement to immersive music, especially in virtual and augmented reality, demand for high-density loudspeaker arrays (HDLAs), consisting of 24 or more individually addressable loudspeakers is increasing. With only a few dozen publicly accessible systems around the world, HDLAs are rare1, necessitating artistic and technical exploration. The work presented in this thesis details the culmination of four years of aesthetic and technical practice in composition and sound design for high- density loudspeaker arrays as an attempt to solidify existing standards and posit new practices. technical achievements include a pipeline to create repeatable and portable spatial audio mixes across arbitrary loudspeaker arrays, rapid spatial sound prototyping, and digital audio workstation workflow for 3-D soundscape creation. Aesthetic explorations have resulted in a distinct compositional voice, utilizing spatial audio systems as an instrument. Compositions specific to one venue may take advantage of the unique characteristics of a venue, such as loudspeaker layout, loudspeaker quantity, and room acoustics. -

Splatterhouse Por Valveider

ANÁLISIS PERIFÉRICO REVISIÓN Satan’s Hollow Visual Memory Unit Mortal Kombat Go Go Ackman El viaje comienza Master of Darkness Turok 2 Seeds of Evil Great Circus Mystery SimAnt TMNT 2 BattleNexus Número 23 – Octubre 2015 INDICE Editorial por Skullo ..................................................03 Análisis Satan’s Hollow por Skullo ........................................... 04 Go Go Ackman por Skullo ........................................... 06 Master of Darkness por Skullo ................................... 09 Turok 2 Seeds of Evil por El Mestre ............................ 12 Great Circus Mystery por Skullo................................. 16 TMNT 2 BattleNexus por Skullo ................................. 19 Sim Ant por Alf........................................................... 23 Pausatiempos por Skullo ............................... 27 Periféricos Visual Memory Unit por Valveider.............................. 28 Revisión Mortal Kombat El viaje comienza por Skullo ............. 30 Personaje BearTank por Skullo .................................................... 33 Especial Splatterhouse por Valveider ....................................... 35 Maquetación: Skullo Todas las imágenes y nombres que aparecen en esta revista son propiedad de sus respectivas marcas, y se usan simplemente a modo informativo. Las opiniones mostradas en esta revista pertenecen al redactor de cada artículo. EDITORIAL Buenas a todos, en el momento en el cual escribo esto no estoy del todo seguro de la fecha en la cual habrá salido este número, ya -

Sega Genesis

Sega Genesis Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 3 Ninjas Kick Back Psygnosis 6-Pak Sega 6-Pak: Not For Resale Sega 6-Pak: Majesco Rerelease Sega / Majesco Sales 688 Attack Sub Sega Aaahh!!! Real Monsters Viacom New Media Aaahh!!! Real Monsters: Majesco Rerelease Viacom New Media Aaahh!!! Real Monsters: Accolade/Ballistic Rerelease Viacom New Media Aaahh!!! Real Monsters: Accolade/Ballistic Rerelease - Plastic Case Viacom New Media Action 52 Active Enterprises Addams Family, The Flying Edge Adventures of Batman & Robin, The Sega Adventures of Mighty Max, The Ocean Adventures of Mighty Max, The: ESRB Rerelease Ocean Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, The Absolute Entertainment Aero the Acro-Bat Sunsoft Aero the Acro-Bat 2 Sunsoft Aerobiz Koei Aerobiz Supersonic Koei After Burner II Sega Air Buster Kaneko Air Diver Seismic Aladdin, Disney's Sega Aladdin, Disney's: Copyright Text Change Sega Aladdin, Disney's: Accolade/Ballistic Rerelease Sega Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle Sega Alien Storm Sega Alien³ Arena Entertainment Alisia Dragoon Sega Altered Beast Sega American Gladiators GameTek Andre Agassi Tennis TecMagik Animaniacs Konami Animaniacs: Majesco Rerelease Konami Aquatic Games, The: Starring James Pond and the Aquabats Electronic Arts Arcade Classics Sega Arcade Classics: Majesco Rerelease Majesco Arch Rivals Flying Edge Arcus Odyssey Renovation Ariel: The Little Mermaid, Disney's Sega Ariel: The Little Mermaid, Disney's: Cartridge Part # Sega Ariel: The Little Mermaid, Disney's: Majesco Rerelease Sega Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf Sega Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf: Sega Classic Sega Arrow Flash Renovation Art Alive! Sega Art of Fighting Sega Astérix and the Great Rescue Sega Atomic Robo-Kid Treco Atomic Runner Data East ATP Tour Championship Tennis Sega Awesome Possum Tengen B.O.B. -

Game Music Como Produto Cultural Autônomo: Como Ela Ultrapassa Os Limites Do Jogo E Se Insere Em Outras Mídias

revista Fronteiras – estudos midiáticos 13(2): 111-120, maio/agosto 2011 © 2011 by Unisinos – doi: 10.4013/fem.2011.132.04 Game music como produto cultural autônomo: como ela ultrapassa os limites do jogo e se insere em outras mídias Camila Schäfer1 RESUMO A música, nos jogos eletrônicos, além de servir como fundo, também é utilizada como forma de potencializar a experiência de imersão e interatividade do jogador. Considerando seu papel no game como de extrema importância, este artigo procura analisar como a música de videogames se tornou um produto cultural autônomo. Depois de realizada a pesquisa bibliográfica, foi analisado o movimento de autonomização da game music para identificar em quais mídias esse tipo de música se insere atualmente e como ela está se tornando uma manifestação cada vez mais visível também fora do universo dos videogames. A partir desses estudos, da análise dos processos de autonomização, concluiu-se que a game music, além de sua importância para os jogos, constitui-se num novo fenômeno midiático que a cada dia cresce e contagia mais pessoas ao redor do mundo. Palavras-chave: game music, música, jogos eletrônicos. ABSTRACT The game music as an autonomous cultural product: How it exceeds the limits of the video games and falls in other media. The music in the video games, besides of working as a background, is also used as a way to leverage the experience of immersion and interactivity of the player. Considering its role in the game as extremely important, this article seeks to analyze how the game’s music has become an autonomous cultural product.