Who Is Arminius? a Handbook (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pan-Germanism: Its Methods and Its Fruits

384 Pan-Ge,.ma"ism. [July, ARTICLE III. PAN-GERMANISM: ITS METHODS AND ITS FRUITS. BY CHARLES W. SUPER, ATHENS, OHIO. THE cataclysmic war that broke out in Europe in 1914 will furnish all future historians of civilization with phases of group-psychology wholly new. Moreover, they will have at their command a wealth of material far greater than all their predecessors. For one thing, we see at the head of the cen tral alliance a people who in the past made notable contribu tions to the arts and sciences, to literature and philosophy, and especially to music, joining hands with another people who never contributed anything whatever to the progress of the world, whose slow march across the world's stage has been marked with destruction only. For another, we see a people who have developed an educational system that has been admired and copied by other countries for several de cades, and by means of which it has brought its entire pop ulation to the highest pitch of collective efficiency, but whose moral standard has not advanced beyond what it was three, perhaps thirteen, centuries ago. We have here a demonstra tion that a state system of education may become a curse quite as much as a blessing to mankind. Ever since the foundation of our RepUblic it has been proclaimed from pul pit and platform, in books and periodicals without number, that its perpetuity depends upon popular education. It has been assumed, because· regarded as needing no proof, that Digitized by Google 1918.] Pan-G ermanism. 385 an educated people is also an enlightened people, a humane people, a moral people. -

Resettlement Into Roman Territory Across the Rhine and the Danube Under the Early Empire (To the Marcomannic Wars)*

Eos C 2013 / fasciculus extra ordinem editus electronicus ISSN 0012-7825 RESETTLEMENT INTO ROMAN TERRITORY ACROSS THE RHINE AND THE DANUBE UNDER THE EARLY EMPIRE (TO THE MARCOMANNIC WARS)* By LESZEK MROZEWICZ The purpose of this paper is to investigate the resettling of tribes from across the Rhine and the Danube onto their Roman side as part of the Roman limes policy, an important factor making the frontier easier to defend and one way of treating the population settled in the vicinity of the Empire’s borders. The temporal framework set in the title follows from both the state of preser- vation of sources attesting resettling operations as regards the first two hundred years of the Empire, the turn of the eras and the time of the Marcomannic Wars, and from the stark difference in the nature of those resettlements between the times of the Julio-Claudian emperors on the one hand, and of Marcus Aurelius on the other. Such, too, is the thesis of the article: that the resettlements of the period of the Marcomannic Wars were a sign heralding the resettlements that would come in late antiquity1, forced by peoples pressing against the river line, and eventu- ally taking place completely out of Rome’s control. Under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, on the other hand, the Romans were in total control of the situation and transferring whole tribes into the territory of the Empire was symptomatic of their active border policies. There is one more reason to list, compare and analyse Roman resettlement operations: for the early Empire period, the literature on the subject is very much dominated by studies into individual tribe transfers, and works whose range en- * Originally published in Polish in “Eos” LXXV 1987, fasc. -

Speer: an Artist Or a Monster?

Constructing the Past Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 14 2006 Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Emily K. Ergang Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Ergang, Emily K. (2006) "Speer: An Artist or a Monster?," Constructing the Past: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/14 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Abstract This article discusses the life of Albert Speer, who was hired as an architect by Hitler. It describes him as being someone who worked for a career and ignored the political implications of who he was working for. This article is available in Constructing the Past: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/14 Constructing the Past Speer: An Artist or a Monster? Emily Kay Ergang The regime of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party produced a number of complex and controversial. -

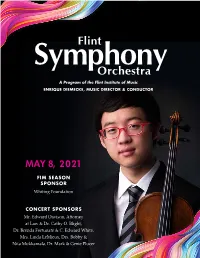

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Aaron Mumford Boehlert Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Boehlert, Aaron Mumford, "Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 136. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/136 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hitler’s Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Senior Project submitted to the Division of Arts of Bard College By Aaron Boehlert Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 2017 A. Boehlert 2 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the infinite patience, support, and guidance of my advisor, Olga Touloumi, truly a force to be reckoned with in the best possible way. We’ve had laughs, fights, and some of the most incredible moments of collaboration, and I can’t imagine having spent this year working with anyone else. -

Germania TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 16 TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 17

TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 15 Part I Germania TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 16 TEG1 8/2/2004 2:52 PM Page 17 1 Land and People The Land The heartland of the immense area of northern Europe occupied by the early Germanic peoples was the great expanse of lowland which extends from the Netherlands to western Russia. There are no heights here over 300 metres and most of the land rises no higher than 100 metres. But there is considerable variety in relief and soil conditions. Several areas, like the Lüneburg Heath and the hills of Schleswig-Holstein, are diverse in both relief and landscape. There was until recent times a good deal of marshy ground in the northern parts of the great plain, and a broad belt of coastal marshland girds it on its northern flank. Several major rivers drain the plain, the Ems, Weser and Elbe flowing into the North Sea, the Oder and the Vistula into the Baltic. Their broad valleys offered attrac- tive areas for early settlement, as well as corridors of communication from south to north. The surface deposits on the lowland largely result from successive periods of glaciation. A major influence on relief are the ground moraines, comprising a stiff boulder clay which produces gently undu- lating plains or a terrain of small, steep-sided hills and hollows, the latter often containing small lakes and marshes, as in the area around Berlin. Other features of the relief are the hills left behind by terminal glacial moraines, the sinuous lakes which are the remains of melt-water, and the embayments created by the sea intruding behind a moraine. -

A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site

The Culture of Memory and the Role of Archaeology: A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site Laurel Fricker A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 18, 2017 Advised by Professor Julia Hell and Associate Professor Kerstin Barndt 1 Table of Contents Dedication and Thanks 4 Introduction 6 Chapter One 18 Chapter Two 48 Chapter Three 80 Conclusion 102 The Museum and Park Kalkriese Mission Statement 106 Works Cited 108 2 3 Dedication and Thanks To my professor and advisor, Dr. Julia Hell: Thank you for teaching CLCIV 350 Classical Topics: German Culture and the Memory of Ancient Rome in the 2016 winter semester at the University of Michigan. The readings and discussions in that course, especially Heinrich von Kleist’s Die Hermannsschlacht, inspired me to research more into the figure of Hermann/Arminius. Thank you for your guidance throughout this entire process, for always asking me to think deeper, for challenging me to consider the connections between Germany, Rome, and memory work and for assisting me in finding the connection I was searching for between Arminius and archaeology. To my professor, Dr. Kerstin Barndt: It is because of you that this project even exists. Thank you for encouraging me to write this thesis, for helping me to become a better writer, scholar, and researcher, and for aiding me in securing funding to travel to the Museum and Park Kalkriese. Without your support and guidance this project would never have been written. -

Kennewick Man and Asatru

7/17/12 Irminsul Ættir Archives - Kennewick Man and Asatru Kennewick Man and Asatru Battle Over BonesArchaeology (Jan/Feb 1997) TriCity Herald (Kennewick Man The debate that spans 9,000 years) DejanewsSearch on Kennewick Man or alt.religion.asatru The Irminsul Ættir Position The Kennewick Man Story by Susan Granquist In October of 1996, members of the Asatru Folk Assembly (AFA) filed a complaint against the Army Corps of Engineers seeking an injunction to prevent the Corps from turning the ancient skeleton referred to in the media as the Kennewick Man over to the Umatilla Tribes under the Native Graves Protection and Repatriation Act based on religious principles of Asatru, an ancient preChristian, ethnic religion. However there are a number of things that need to be known in order to for the public and court to fairly evaluate the claim that might not be apparent to those unfamiliar with this faith. The complaint, filed in the United States District Court for the District of Oregon, CV No. CV96 1516 JE by the Asatru Folk Assembly, Stephen A. McNallen, and William Fox versus the United States of America, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Ernest J. Harrell, Donald R. Curtis, and Lee Turner, Judicial Review of Agency Action (Administrative Procedure Act), 5 USC & 706; violation of 42 USC & 1981 and 42 USC & 1983; Deprivation of Constitutional Rights; violation of Native American Graves Protection Act; Request for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief and for Attorney Fees. Section 2. "This action relates to the human skeletal remains discovered in July 1996 in eastern Washington commonly known as the 'Richland Man' and sometimes as the 'Kennewick Man' and which are the subject of a notice of intent to repatriate issued by the U.S. -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 1 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch, 1870 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 2 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch (1838–1920) Complete Symphonies CD 1 Symphony No. 1 op. 28 in E flat major 38'04 1 Allegro maestoso 10'32 2 Intermezzo. Andante con moto 7'13 3 Scherzo. Presto 5'00 4 Quasi Fantasia. Grave 7'30 5 Finale. Allegro guerriero 7'49 Symphony No. 2 op. 36 in F minor 39'22 6 Allegro passionato, ma un poco maestoso 15'02 7 Adagio ma non troppo 13'32 8 Allegro molto tranquillo 10'57 T.T.: 77'30 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 3 13.03.2020 10:56:27 CD 2 1 Prelude from Hermione op. 40 8'54 (Concert ending by Wolfgang Jacob) 2 Funeral march from Hermione op. 40 6'15 3 Entr’acte from Hermione op. 40 2'35 4 Overture from Loreley op. 16 4'53 5 Prelude from Odysseus op. 41 9'54 Symphony No. 3 op. 51 in E major 38'30 6 Andante sostenuto 13'04 7 Adagio ma non troppo 12'08 8 Scherzo 6'43 9 Finale 6'35 T.T.: 71'34 Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino, Conductor cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 4 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Bamberger Symphoniker (© Andreas Herzau) cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 5 13.03.2020 10:56:28 Auf Eselsbrücken nach Damaskus – oder: darüber, daß wir es bei dieser Krone der Schöpfung Der steinige Weg zu Bruch dem Symphoniker mit einem Kompositum zu tun haben, das sich als Geist mit mehr oder minder vorhandenem Verstand in einem In der dichtung – wie in aller kunst-betätigung – ist jeder Körper darstellt (die Bezeichnungen der Ingredienzien der noch von der sucht ergriffen ist etwas ›sagen‹ etwas ›wir- mögen wechseln, die Tatsache bleibt). -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g.