Hyperion Cover Apr 09 2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microtonal University (Mu)

MICROTONAL UNIVERSITY (MU) a virtual microtonal university SCHEDULE September 5, 2021 – August 28, 2022 A Program of the American Festival of Microtonal Music Inc. (AFMM) Johnny Reinhard - Director [email protected] MU’s Definition of “Microtonal Music”: “All music is microtonal music cross-culturally. Twelve-tone equal temperament is in itself a microtonal scale, only it enjoys exorbitant attention and hegemonic power, so we focus on the other tuning arrangements.” Johnny Reinhard, MU Director Financial Structure: $50. annual subscription; after September 1, 2021 annual membership increases to $200. Checks must be made out fully to: American Festival of Microtonal Music Inc. Or, please go to www.afmm.org and look for the PayPal button at the bottom of the American Festival of Microtonal Music’s website on the front page. MU c/o Johnny Reinhard Director, MU/AFMM 615 Pearlanna Drive San Dimas, CA 91773 347-321-0591 [email protected] 2 MU MU – a virtual microtonal university Beginning September 5, 2021, the American Festival of Microtonal Music (AFMM) presents a new project: MU Faculty members are virtuoso instrumentalists, composers and improvisers Meredith Borden (voice/interstylistic) Svjetlana Bukvich (synthesizer/electronics) Jon Catler (guitar/rock) Philipp Gerschlauer (saxophone/jazz) Johnny Reinhard (bassoon/interstylistic) – Director of MU Manfred Stahnke (viola/music composition) Michael Vick (multi-instrumental/technology) Using various platforms, MU will make available a host of different courses, instruction, entertainment, connections, -

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

©2011 Campus Circle • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 Wilshire Blvd

©2011 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON TIME “It’s a heightened, almost hallucinatory sensual experience, and ESSENTIAL VIEWING FOR SERIOUS MOVIEGOERS.” RICHARD CORLISS THE NEW YORK TIMES “A COSMIC HEAD MOVIE OF THE MOST AMBITIOUS ORDER.” MANOHLA DARGIS HOLLYWOOD WEST LOS ANGELES EXCLUSIVE ENGAGEMENTS START FRIDAY, MAY 27 at Sunset & Vine (323) 464-4226 at W. Pico & Westwood (310) 281-8233 FOX SEARCHLIGHT FP. (10") X 13" CAMPUS CIRCLE - 4 COLOR WEDNESDAY: 5/25 ALL.TOL-A1.0525.CAM CC CC JL JL 4 COLOR Follow CAMPUS CIRCLE on Twitter @CampusCircle campus circle INSIDE campus CIRCLE May 25 - 31, 2011 Vol. 21 Issue 21 Editor-in-Chief 6 Yuri Shimoda [email protected] Film Editor 4 14 [email protected] Music Editor 04 FILM MOVIE REVIEWS [email protected] 04 FILM PROJECTIONS Web Editor Eva Recinos 05 FILM DVD DISH Calendar Editor Frederick Mintchell 06 FILM SUMMER MOVIE GUIDE [email protected] 14 MUSIC LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE Editorial Interns Intimate and adventurous music festival Dana Jeong, Cindy KyungAh Lee takes place over Memorial Day weekend. 15 MUSIC STAR WARS: IN CONCERT Contributing Writers Tamea Agle, Zach Bourque, Kristina Bravo, Mary Experience the legendary score Broadbent, Jonathan Bue, Erica Carter, Richard underneath the stars at Hollywood Bowl. Castañeda, Amanda D’Egidio, Jewel Delegall, Natasha Desianto, Stephanie Forshee, Jacob Gaitan, Denise Guerra, Ximena Herschberg, 15 MUSIC REPORT Josh -

The Anchor, Volume 118.04: September 22, 2004

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 2004 The Anchor: 2000-2009 9-22-2004 The Anchor, Volume 118.04: September 22, 2004 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_2004 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 118.04: September 22, 2004" (2004). The Anchor: 2004. Paper 16. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_2004/16 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 118, Issue 4, September 22, 2004. Copyright © 2004 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 2000-2009 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 2004 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. September 2004 tHe "h" word ••••••• Hope College Holland, Michigan A student-run nonprofit publication Serving the Hope College Community for 118 years Campus HOUSE MAKEOVER TIME Briefs Campus ministries teams with Jubilee to English prof rejuvenate community iiini publishes new The Extreme House Makeover, held this past Saturday, was sponsored by Ju- children's book bilee Ministries, a local Christian out- Hcalhcr Sellers, professor f. ! reach program. of English, has a new book on Campus ministries promoted the the market. "Spike and project in chapel and the Gathering for Cubby's Ice Cream Island several weeks, but were still over- Adventure," features Seller's whelmed by the 200 students who turned corgi and aulhor/illusiraior out to help improve a house for low-in- Amy Young's black lab as two come families on 15th Street, as well as dogs trapped in a boat during businesses on 17ih Street. -

Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever PDF Book

TRANSCEND: NINE STEPS TO LIVING WELL FOREVER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ray Kurzweil,Terry Grossman | 480 pages | 21 Dec 2010 | RODALE PRESS | 9781605292076 | English | Emmaus, PA, United States Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever PDF Book Archived from the original on 17 October Like some other Kurzweil books, he really catches your attention with some insane predictions. Error rating book. These are brain extenders that we have created to expand our own mental reach. He was involved with computers by the age of 12 in , when only a dozen computers existed in all of New York City, and built computing devices and statistical programs for the predecessor of Head Start. He obtained a B. Each chapter has its purpose and a plan for us readers to start applying the information. Ray's ideas are definitely futuristic. Inventing is a lot like surfing: you have to anticipate and catch the wave at just the right moment. The only thing I didn't like was their suggestion to eat so many dietary supplements such as vitamins and not including more defined suggestions on how to combine them. Aug 04, DJ rated it liked it. Products include the Kurzweil text-to-speech converter software program, which enables a computer to read electronic and scanned text aloud to blind or visually impaired users, and the Kurzweil program, which is a multifaceted electronic learning system that helps with reading, writing, and study skills. This is a 'how to Top charts. In , Visioneer, Inc. Development of these technologies was completed at other institutions such as Bell Labs, and on January 13, , the finished product was unveiled during a news conference headed by him and the leaders of the National Federation of the Blind. -

ROBERT WILSON / PHILIP GLASS LANDMARK EINSTEIN on the BEACH BEGINS YEARLONG INTERNATIONAL TOUR First Fully Staged Production in 20 Years of the Rarely Performed Work

For Immediate Release March 13, 2012 ROBERT WILSON / PHILIP GLASS LANDMARK EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH BEGINS YEARLONG INTERNATIONAL TOUR First Fully Staged Production in 20 Years of the Rarely Performed Work Einstein on the Beach 2012-13 trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZ5hTfDzU9A&feature=player_embedded#! The Robert Wilson/Philip Glass collaboration Einstein on the Beach, An Opera in Four Acts is widely recognized as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century. Although every performance of the work has attracted a sold-out audience, and the music has been recorded and released, few people have actually experienced Einstein live. An entirely new generation—and numerous cities where the work has never been presented—will have the opportunity during the 2012-2013 international tour. The revival, helmed by Wilson and Glass along with choreographer Lucinda Childs, marks the first full production in 20 years. Aside from New York, Einstein on the Beach has never been seen in any of the cities currently on the tour, which comprises nine stops on four continents. • Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon presents the world premiere at the Opera Berlioz Le Corum March 16—18, 2012. • Fondazione I TEATRI di Reggio Emilia in collaboration with Change Performing Arts will present performances on March 24 & 25 at Teatro Valli. • From May 4—13, 2012, the Barbican will present the first-ever UK performances of the work in conjunction with the Cultural Olympiad and London 2012 Festival. • The North American premiere, June 8—10, 2012 at the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts, as part of the Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity, represents the first presentation in Canada. -

2045: the Year Man Becomes Immortal

2045: The Year Man Becomes Immortal From TIME magazine. By Lev Grossman Thursday, Feb. 10, 2011 On Feb. 15, 1965, a diffident but self-possessed high school student named Raymond Kurzweil appeared as a guest on a game show called I've Got a Secret. He was introduced by the host, Steve Allen, then he played a short musical composition on a piano. The idea was that Kurzweil was hiding an unusual fact and the panelists — they included a comedian and a former Miss America — had to guess what it was. On the show , the beauty queen did a good job of grilling Kurzweil, but the comedian got the win: the music was composed by a computer. Kurzweil got $200. Kurzweil then demonstrated the computer, which he built himself — a desk-size affair with loudly clacking relays, hooked up to a typewriter. The panelists were pretty blasé about it; they were more impressed by Kurzweil's age than by anything he'd actually done. They were ready to move on to Mrs. Chester Loney of Rough and Ready, Calif., whose secret was that she'd been President Lyndon Johnson's first-grade teacher. But Kurzweil would spend much of the rest of his career working out what his demonstration meant. Creating a work of art is one of those activities we reserve for humans and humans only. It's an act of self-expression; you're not supposed to be able to do it if you don't have a self. To see creativity, the exclusive domain of humans, usurped by a computer built by a 17-year-old is to watch a line blur that cannot be unblurred, the line between organic intelligence and artificial intelligence. -

December 2000

21ST CENTURY MUSIC DECEMBER 2000 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 (print) and $42.00 (e-mail) per year; subscribers to the print version elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $8.00 (print) and $4.00 (e-mail) Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. e-mail: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2000 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Resonance, Decisions, Freedom: The Music of Peter Zummo With accuracy and humor, Peter Zummo (born 1948) often describes his unique music as “minimalism plus a whole lot more.” He is an important exponent of the American contemporary classical tradition whose compositions explore the methodologies of not just minimalism, but also jazz, world music, and rock, while seeking to create freedom in ensemble situations. Zummo’s realization of the contemporary urge to make music that behaves like “Nature in its manner of operation” (John Cage) is to encourage spontaneous, individual decisions within a self-structuring, self-negotiating group of performers. His scores provide unique strategies (such as a “matrix of overlapping systems,” freely modulating repetition rates, etc.) and materials for achieving that aim. Zummo has also designed new instrumental techniques for the trombone, valve trombone, dijeridu, euphonium, electronic instruments, and voice, and performed and recorded his work and that of others worldwide. The origin and nature of these ensemble freedoms and instrumental techniques form the subjects of this essay. (The composer’s comments, in quotes below, are from an interview on August 24, 2006, in New York City.) Instruments (1980) Following his early classical music studies and graduation from Wesleyan University, Zummo moved to New York City in 1975. “At the time, I was aware of the Fluxus movement, the Grand Union [a New York-based ‘anarchistic democratic theater collective’ (Steve Paxton) of avant-garde dancers formed in 1970] and that generation of free-thinking artists. I respected them a lot. I considered myself half a generation behind them but shared their mindset of free-ranging exploration. -

Modernworks Musician Bios

MEET The ModernWorks! Musicians Madeleine Shapiro - Bio Madeleine has presented her VOICES cello recital at colleges and universities throughout the United States. Her concerts have included numerous premiere performances of recent works for cello, and cello and electronics, many of which were written specially for her by a wide variety of American, European and Asian composers. She is a recipient of two Performance Incentive Awards from the American Composers Forum to assist in the premieres of new works. Recent appearances include a concert of works for cello and electronics at the avant-garde Logos Foundation in Ghent, Belgium and two tours of Italy with performances and masterclasses at The American Academy and the Nuovi Spazi Musicali festival in Rome; the Orsini Castle in Avezzano, and the conservatories of Parma and Castelfranco Veneto. Madeleine performs regularly at colleges and performing arts series in the East and Midwest United States. Recent appearances have included the Forefront Series at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, Rutgers University, University of Maryland and the "Solo Flights" series sponsored by the Composers Collaborative in New York City. Madeleine appeared twice in recital at the Instituto Brazil-Estados Unidos in Rio De Janiero, Brazil and participated in the 3rd and 5th International Cello Encounters, also in Rio de Janiero. From 1974-1996, Madeleine was the cellist and co-director of The New Music Consort, an ensemble specializing in the performance of twentieth century music. With the Consort, Madeleine toured the United States and Europe, and participated in numerous premiere performances of works by such eminent composers as Milton Babbitt, John Cage, Charles Wuorinen and Mario Davidovsky as well as emerging American, European and Asian composers. -

![Factorial [Five][Five] Factorialfactorial](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5778/factorial-five-five-factorialfactorial-4045778.webp)

Factorial [Five][Five] Factorialfactorial

[Five] Factorial [Five][Five] FactorialFactorial ISBN 0-9754468-4-3 50800> 94780975 46843 ! Factorial Press ! 5! [Five] Factorial Summer 2006 Copyright © 2006 Factorial & Contributors Edited by Sawako Nakayasu Managing Editor: Benjamin Basan Ants: Chris Martin (front cover) Kenjiro Okazaki (back cover & section headings) Many thanks to: Jerrold Shiroma, Eugene Kang, Eric Selland, the Santa Fe Art Insitute & Witter Bynner Foundation, Shigeru Kobayashi, Yotsuya Art Studium, Yu Nakai, & Naoki Matsumoto. ISSN 1541-2660 ISBN 0-9754468-4-3 & 978-0-9754468-4-3 http://www.factorial.org/ Modernist Japanese Poetry Sampler KATUE KITASONO from Conical Poems A Cornet-Style Scandal Disconnect the lead cone and hammer the yellow dream in a glass bottle. If even then a metal walking stick leaps up, it’s best to take off your glasses and calmly lie down. In a flash, space turns to glass; pigs exhale firefly-colored gas and crack in the brilliant beyond. 5 Those Countless Stairs and Crystal Breasts of the Boy with a Glass Ribbon Tied Around His Neck Snail-colored space warps, tears, flies off. Then, from a direction of total liquid, a boy with golden stripes showed the circle of a wise forehead and came sliding here into the proscenium. 6 Transparent Boy’s Transparent Boy’s Shadow O boy whom I love! O beautiful rose boy who climbs the sky’s silver line. Stare at tragedy of light of eternity’s ocean, eternity’s acrobat. Dream, dream is a shining wheel, with wheel of tears and crystal wheel carrying away your arch and bouquet in summer pebbles. -

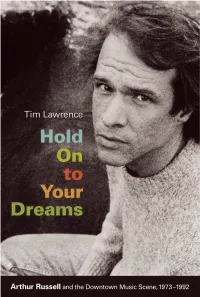

Tim Lawrence

Hold On to Your Dreams Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–1992 Tim Lawrence Hold On to Your Dreams is the first biography of the musician and composer Arthur Russell, one of the most important but least known contributors to New York’s downtown music scene during the 1970s and 1980s. With the exception of a few dance recordings, including “Is It All Over My Face?” and “Go Bang! #5,” Russell’s pioneering music was largely forgotten until 2004, when the posthumous release of two albums brought new attention to the artist. This revival of interest gained momentum with the issue of additional albums and the documentary film Wild Combination. Based on interviews with more than seventy of his collaborators, family members, and friends, Hold On to Your Dreams provides vital new information about this singular, eccentric musician and his role in the boundary-breaking downtown music scene. Tim Lawrence traces Russell’s odyssey from his hometown of Oskaloosa, Iowa, to countercultural San Francisco, and eventually to New York, where he lived from 1973 until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1992. Resisting definition while dreaming of commercial success, Russell wrote and performed new wave and disco as well as quirky rock, twisted folk, voice-cello dub, and hip-hop-inflected pop. “He was way ahead of other people in understanding that the walls between concert music and popular music and avant-garde music were illusory,” comments the composer Philip Glass. “He lived in a world in which those walls weren’t there.” Lawrence follows Russell across musical genres and through such vital downtown music spaces as the Kitchen, the Loft, the Gallery, the Paradise Garage, and the Experimental Intermedia Foundation.