Post-9/11 American War Fiction in Dialogue with Official-Media Discourse (Doctoral Dissertation, Duquesne University)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y Ear)

6/26/2019 American Lit Summer Reading 2019-20 - Google Docs 11 th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y ear) Welcome to American Literature! This summer assignment is meant to keep your reading and writing skills fresh. You should choose carefully —select books that will be interesting and enjoyable for you. Any assignments that do not follow directions exactly will not be accepted. This assignment is due Friday, August 16, 2019 to your American Literature Teacher. This will count as your first formative grade and be used as a diagnostic for your writing ability. Directions: For your summer assignment, please choose o ne of the following books to read. You can choose if your book is Fiction or Nonfiction. Fiction Choices Nonfiction Choices Catch 22 by Joseph Heller The satirical story of a WWII soldier who The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs. An account thinks everyone is trying to kill him and hatches plot after plot to keep of a young African‑American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend from having to fly planes again. Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison The story of an abusive “nuanced and shattering” ( People ) and “mesmeric” ( The New York Southern childhood. Times Book Review ) . The Known World by Edward P. Jones The story of a black, slave Outliers / Blink / The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating owning family. statistical studies of everyday phenomena. For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway A young American The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story by Richard Preston There is an anti‑fascist guerilla in the Spanish civil war falls in love with a complex outbreak of ebola virus in an American lab, and other stories of germs woman. -

Shrader's "The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia •Fi a Military

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 24 Issue 6 Article 6 12-2004 Shrader's "The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia – A Military History, 1992-1994" - Book Review Tal Tovy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tovy, Tal (2004) "Shrader's "The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia – A Military History, 1992-1994" - Book Review," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 24 : Iss. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol24/iss6/6 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Here, many notable intellectual Jewish figures of the time are spoken of in detail. This is the real highlight of the book, by quoting the sources and presenting his interpretation in the context, many faces and names become conceivable and it fosters the enjoyment of the book. All in all, Jews in Poland-Lithuania in the Eighteenth Century is not for the casual reader. Students of Jewish studies, eastern European history and even the Holocaust will find this understandable and useful; to others the information provided may just be too obscure. However, anyone of Jewish or even Eastern European background can definitely find valuable information in Gershon’s book. -

RETHINKING ISLAMIZED BALKANS Edoardo CORRADI Alpha Institute of Geopolitics and Intelligence E-Mail

RETHINKING ISLAMIZED BALKANS Edoardo CORRADI Alpha Institute of Geopolitics and Intelligence E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Could Islamized Balkans be a threat for European Union security? The foreign fighters phenomenon exists in Western Balkans countries but it is overestimated. The population in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania is majority Sunni Muslim, and in former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 33% of Macedonian are Muslims. Balkans Islamism is westernized and not radical, because of Balkans history. The presence of Balkan foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq is not because of Sunni Islam (Salafi), but because of socio-economic condition of these countries. A low degree of development, high youth unemployment and low GDP per capita are responsible of the re- Islamization phenomenon and its radicalism. The European Union should cooperate with the Balkan States in order to fight this phenomenon and to prevent the future radicalization of the younger population. This work will analyse the Balkans Islam through the history and Samuel Huntington’s theoretical analysis. The analysis of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations is necessary to understand how ethnic conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina and, also, in all Balkans are not guided by religious or ethnical difference, but from regional and international political projects. Keywords: foreign fighters; terrorism; Islam; Islamic State; Western Balkans 1. Introduction The only European countries have a Muslim majority are located in the Western Balkans. The European security system has recently highlighted the jihadist threat in this context. For instance, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania and Kosovo are nowadays considered the cradle of the European jihadists and the Islamic terrorism’s transit countries. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Award Winners

RITA Awards (Romance) Silent in the Grave / Deanna Ray- bourn (2008) Award Tribute / Nora Roberts (2009) The Lost Recipe for Happiness / Barbara O'Neal (2010) Winners Welcome to Harmony / Jodi Thomas (2011) How to Bake a Perfect Life / Barbara O'Neal (2012) The Haunting of Maddy Clare / Simone St. James (2013) Look for the Award Winner la- bel when browsing! Oshkosh Public Library 106 Washington Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54901 Phone: 920.236.5205 E-mail: Nothing listed here sound inter- [email protected] Here are some reading suggestions to esting? help you complete the “Award Winner” square on your Summer Reading Bingo Ask the Reference Staff for card! even more awards and winners! 2016 National Book Award (Literary) The Fifth Season / NK Jemisin Pulitzer Prize (Literary) Fiction (2016) Fiction The Echo Maker / Richard Powers (2006) Gilead / Marilynn Robinson (2005) Tree of Smoke / Dennis Johnson (2007) Agatha Awards (Mystery) March /Geraldine Brooks (2006) Shadow Country / Peter Matthiessen (2008) The Virgin of Small Plains /Nancy The Road /Cormac McCarthy (2007) Let the Great World Spin / Colum McCann Pickard (2006) The Brief and Wonderous Life of Os- (2009) A Fatal Grace /Louise Penny car Wao /Junot Diaz (2008) Lord of Misrule / Jaimy Gordon (2010) (2007) Olive Kitteridge / Elizabeth Strout Salvage the Bones / Jesmyn Ward (2011) The Cruelest Month /Louise Penny (2009) The Round House / Louise Erdrich (2012) (2008) Tinker / Paul Harding (2010) The Good Lord Bird / James McBride (2013) A Brutal Telling /Louise Penny A Visit -

Songs of Perkei Avot with San Slomovits and Rabbi Dobrusin

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Summer of Thoughts Year in Permit No. 85 Ann Arbor/ for the Review Nahalal High 5772 Connections Holidays Page 4 Page 14 Page 22 September 2012 Elul 5772/Tishrei 5773 Volume XXXVII: Number 1 FREE Sukkarnival Celebration at the JCC Laurie Barnett installed as Halye Aisner, special to the WJN Federation president he Jewish Community Center of David Shtulman, special to the WJN Greater Ann Arbor will host a Suk- More than 100 people were present as Laurie T karnival celebration on Sunday, Sep- Barnett was installed as the 14th Jewish Fed- tember 30, from noon-3 p.m. at the JCC. eration of Greater Ann Arbor president on Sukkarnival will continue many of the JCC’s May 30, succeeding classic Apples and Honey program tradi- Ed Goldman. Bar- tions. Festivities for Sukkarnival will include nett said that ev- a celebration of Sukkot, carnival–themed ery president has a games, face painting and bouncers. A special word that symbol- welcome to Ann Arbor newcomers, Jewish izes his or her term organization displays, vendor displays and as president. Her a Camp Raanana reunion will all be part of word will be “wel- the fun. Israeli food, kosher baked goods and come,” represent- lunch will be available for purchase along ing her desire for with gifts and Judaica items. The JCC’s Early Federation to be Childhood Center will also hold a holiday the most open and bake sale at the event. -

Fire and Forget This Interview Was Generously Shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group

Common Reading Program 2014 St. Cloud State University Teaching and Discussion Guide 2 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Table of Contents I. Book Summary 3 II. A Talk with Matt 4-8 III. Iraq and Afghanistan War Timeline 9 IV. Map of Afghanistan 10 V. Map of Iraq 11 VI. Glossary 12 VII. Book Discussion and Facilitation guide 13-14 VIII. Teaching about wars in Iraq and Afghanistan 15 IX. Related Activities 16 X. National Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 17 XI. Local Veterans Resources and Support Organizations 18 XII. Related Books 19 XIII. Documentaries 20 XIV. Feature Film Suggestions 21 3 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide Book Summary The stories aren't pretty and they aren't for the faint of heart. They are gritty, haunting, shocking—and unforgettable. Television reports, movies, newspapers, and blogs about the recent wars have offered snapshots of the fighting there. But this anthology brings us a chorus of powerful storytellers—some of the first bards from our recent wars, emerging voices and new talents—telling the kind of panoramic truth that only fiction can offer. What makes these stories even more remarkable is that all of them are written by men and women whose lives were directly engaged in the wars—soldiers, Marines, and an army spouse. Featuring a forward by National Book Award-winner Colum McCann, this anthology spans every era of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from Baghdad to Brooklyn, from Kabul to Fort Hood. 4 Common Reading Program 2014| Guide A Talk with Matt Gallagher and Roy Scranton -Editors of Fire and Forget This interview was generously shared with the Common Reading Program by Perseus Publishing Group. -

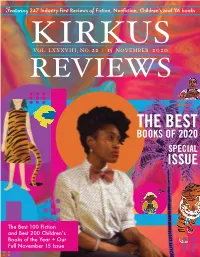

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

A Lesser Imitation (?): How Redeployment Recalls, Expands, and Departs from the Things They Carried

GRACE HOWARD A Lesser Imitation (?): How Redeployment Recalls, Expands, and Departs from The Things They Carried ar is, by far, an incredibly fascinating subject worthy of study. War is compelling, devastating, destructive, restorative, exhausting, enthralling, morally complex, and something that often raises a number of questions. WWar frequently leaves participants, bystanders, and environments forever changed. Writer Tim O’Brien thoroughly describes war in a complicated manner: “War is hell […] war is also mystery and terror and adventure and courage and discovery and holiness and pity and despair and longing and love. War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery. War makes you man; war makes you dead” (O’Brien 80). There are aspects of war which are timeless (aggressive conflict between two or more ethnic or religious groups, countries, etc.), and other ever-changing aspects, such as military strategies and battlefield technologies. Even more fascinating is the idea of how exactly war is documented and processed over time—whether it be via veteran’s journals, poetry, memoirs, newspapers and other media, documentaries, blogs, Hollywood blockbusters, or most recently, several fictional texts that grapple with the contemporary conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. From about 2011 onward, there has been a surge of novels and short stories that delve into American perspectives of these conflicts. Of particular interest is Phil Klay’sRedeployment , a compilation of short stories that bears considerable resemblance to (and some departures from) a collection published twenty-four years prior: Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. Many debates about Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried1 (1990) attempt to designate the book as part of a particular genre, and such debates often become circuitous and fail to reach a consensus about the book. -

SHAWNEE STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD of TRUSTEES Meeting

SHAWNEE STATE UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES Meeting Minutes December 15, 2017 Call to Order Chairperson Williams called the meeting to order at 11:32 a.m. noting the meeting was in compliance with RC § 121.22(F). Roll Call Members Present: Mr. Evans, Mr. Furbee, Ms. Hartop, Ms. Hash, Mr. Howarth, Mr. Watson, Dr. White, Mr. Williams, and Ms. Detty Members Absent: Mr. Rappold; Mr. Moore Prior to the start of the meeting, Trustee Moore notified the Governor’s office by email that he was resigning his position, effectively immediately, and the Board Secretary was copied on the email. Approval of the October 13, 2017 Board Meeting Minutes and Executive Committee Minutes Mr. Watson moved and Mr. Furbee seconded a motion to approve the October 13, 2017 minutes. Without discussion, the Board unanimously approved said minutes. Approval of the December 15, 2017 Agenda Dr. White moved and Mr. Howarth seconded a motion to approve the December 15, 2017 agenda. Without discussion, the Board unanimously approved the December 15, 2017 agenda. Consent Agenda 1. Resolution F21-17, Approval of Shawnee State University Textbook Program 2. Resolution F22-17, Approval of FY17 Efficiency Report 3. Resolution F23-17, Approval of the Give Back Go Forward Program Chair Williams directed the Board to review the action items on the Consent Agenda and asked if anyone wished to remove any items from the Consent Agenda. December 15, 2017 SSU Board of Trustees Minutes Page 2 of 6 There being no objections, Chair Williams declared that items 1-3 will remain on the agenda and be adopted. -

Education Page 14

Education Page 14 Monday and Tuesday lectures are in Orchestra Hall, and Wednesday and Thursday lectures are in Chautauqua Hall. The Chautauqua Prize Vearl Smith Historic 10:30 a.m., Monday: Redeployment: A Writer’s Journey with Phil Klay Preservation Workshop (Orchestra Hall) After World War I, Louis Simpson wrote: “To a foot-soldier, war is almost Supported by the Vearl Smith Memorial Endowment for Historic Preservation entirely physical. That is why some men, when they think about war, fall silent. 10:30 a.m., Wednesday: Discovering Ohio Architecture with Barbara Powers Language seems to falsify physical life and to betray those who have experi- (Chautauqua Hall) enced it absolutely—the dead.” Discover the richness and diversity of Ohio’s architecture. The sto- Yet, after every war, veterans have taken up the task of rendering the seem- ry of Ohio, from early settlement, through industrial expansion, to mod- ingly unimaginable into words. National Book Award-winning author and Iraq ern times, is reflected in its landmark buildings, urban centers, small towns War veteran Phil Klay will describe his experiences in the Marine Corps, and and the work of specific architects and builders. This program will dis- why he ultimately decided that writing about Iraq was a necessity. cuss broad architectural trends and characteristics of specific styles ex- Klay is a graduate of Dartmouth College and a amined within the context of 19th and 20th century Ohio. Understand- veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps. He served from ing and appreciating historic architecture is key to its preservation. Learn January 2007 to February 2008 in Iraq’s Anbar about the programs offered through the State Historic Preservation Office Province as a Public Affairs Officer.