Renegades and the “Secret World”, C. –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

À Madame / Madame Marie Anne / De Sonnenbourg Née De Mozart2 / À / Salzbourg to Be Delivered to the Tanzmeister= / =Haus.3

0861. LEOPOLD MOZART TO HIS DAUGHTER,1 ST. GILGEN À Madame / Madame Marie Anne / de Sonnenbourg née de Mozart2 / à / Salzbourg To be delivered to the Tanzmeister= / =haus.3 Vienna, 16th April, 1785 We have finally decided to leave here on Thursday4 the 21st in the company of Boudé and her husband; [5] your brother and sister-in-law were firmly resolved to join us on the journey, but now everything is working out awkwardly again,5 and probably nothing will come of it, although everybody has had 6 pairs of shoes made for himself and they are already lying there. You should receive news of how everything is working out from Lintz or Munich, where I always have time to write. The officer Starmberg6 has arrived here, he says the roads are abominable. [10] That lout Wolfegg7 is an officer here; I spoke with him, he told me that the Senior Master of the Hunt, Count Herberstein,8 has laid down his position. Baron von Lehrbach9 is also here, cathedral canon Starmberg10 will come here in May. Villersi11 kisses you a million times, today I went to take leave of her, and did the same yesterday at Herr von Lehman’s,12 where I ate at midday. On Tuesday Baroness von Waldstetten13 will send her horses [15] and we drive to her in Neuburg Nunnery14 |: which is where she always stays now :|, eat there, and back in the evening. I am curious to get to know this lady of my heart, since I was already invisis15 the man of her heart. -

Case 1:15-Cv-00803-KBJ Document 62 Filed 10/13/16 Page 1 of 67

Case 1:15-cv-00803-KBJ Document 62 Filed 10/13/16 Page 1 of 67 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) MICHAEL ROBINSON ) 5330 E Street S.E., Apt. 4 ) Washington, D.C. 20019 ) ) AGNES JOYCE ROBINSON ) 5330 E Street S.E., Apt. 4 ) Washington, D.C. 20019 ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) BRANDON FARLEY ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) SEAN BABCOCK ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) Civil Action No. 15-cv-00803 (KBJ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) THOMAS HILLIGOSS ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) KENNETH MEUSHAW ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) ALAN LARMORE ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) Case 1:15-cv-00803-KBJ Document 62 Filed 10/13/16 Page 2 of 67 TERRENCE WALKER ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) OSIRIS LOPEZ ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) TIMOTHY CORDERO ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County Police Department ) 7600 Barlowe Road ) Landover, MD 20785 ) ) RENALDO MASON ) In his individual capacity ) c/o Prince George’s County -

A Little History of the Schulenburg Family

Fritz Schulenburg-Beetzendorf (Autor) A Little History of the Schulenburg Family https://cuvillier.de/de/shop/publications/6735 Copyright: Cuvillier Verlag, Inhaberin Annette Jentzsch-Cuvillier, Nonnenstieg 8, 37075 Göttingen, Germany Telefon: +49 (0)551 54724-0, E-Mail: [email protected], Website: https://cuvillier.de ForewordfromtheHeadof theSchulenburgFamily On28thofOctober1237,theMargraveandtheBishopofBrandenburgsigned acontract on the distribution oftaxes (“the tithe”)between thechurchand the Margrave’s government. Eighteen witnesses from both sides signed the treaty,whichcanstillbeseenintheMuseumoftheBrandenburgCathedral. OneofthewitnesseswasthepriestofCöln,avillagewhichlaterbecamepart ofBerlin.ThisiswhyBerlinclaimstooriginatein1237.Anotherwitnesswas Wernerus de Sculenburch, who was a knight and the head of the administration of the Margrave’s government; today this person would be called prime minister. Since Wernerus is the oldest proven ancestor of the Schulenburgs,thehistoryofthefamilydatesbackto1237aswell. Sincethenthefamilyhasexperiencedgoodandbadtimesandthelivesofthe family members reflect their respective times. Today, 777 years later, the family consists of 70 male cousins and their family members. A family gatheringtakesplaceeverysecondyear.The109thfamilygatheringtookplace in September 2013 in Vienna which is where the famous JohannͲMatthias SchulenburgmetPrinceEugenroughly300yearsago. As the current Head of the Schulenburg Family, I would like to express my gratitude to Fritz, for writing the first history of the -

The Grand Duke Constantine's Regiment of Cuirassiers of The

Johann Georg Paul Fischer (Hanover 1786 - London 1875) The Grand Duke Constantine’s Regiment of Cuirassiers of the Imperial Russian Army in 1806 signed and dated ‘Johann Paul Fischer fit 1815’ (lower left); dated 1815 (on the reverse); the mount inscribed with title and dated 1806 watercolour over pencil on paper, with pen and ink 20.5 x 29 cm (8 x 11½ in) This work by Johann Georg Paul Fischer is one of a series of twelve watercolours depicting soldiers of the various armies involved in the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts which took place between 1803 and 1815, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo. The series is a variation of a similar set executed slightly earlier, held in the Royal Collection, and which was probably purchased by, or presented to, the Prince Regent. In this work, Fischer depicts various elements of the Russian army. On the left hand side, the Imperial Guard stride forward in unison, each figure looking gruff and determined. They are all tall, broad and strong and as a collective mass they appear very imposing. Even the drummer, who marches in front, looks battle-hardened and commanding. On the right-hand side, a cuirassier sits atop his magnificent steed and there appear to be further cavalry soldiers behind him. There is a swell of purposeful movement in the work, which creates an impressive image of military power. The Russian cuirassiers were part of the heavy cavalry and were elite troops as their ranks were filled up with the best soldiers selected from dragoon, uhlan, jager and hussar regiments. -

History of the Empire

HISTORY OF THE EMPIRE Hogshead sources : Warhammer FRP Rulebook (WFRP) The Enemy Within source pack (TEW) Death on the Reik (DotR) Warhammer City- City of Chaos (M:CoC) Something Rotten in Kislev (SRiK) Death's Dark Shadow (DDS) Marienburg: Sold Down the River (M:SdtR) Apocrypha Too (AP2) Warpstone sources : Cult of Sigmar (CoS) by N. Arne Dam and Tim Eccles Talabheim project (TAL) by John Foody and Noel Welsh with assistance from N. Arne Dam, Anthony Ragan, and myself Selected entries from GW sources : Warhammer Battle, 4th edition: Warhammer Battle, 5th edition: Dwarf Army book (DW) Bretonnia Army book (BRET) Empire Army book (EMP) Skaven Army book (SK) Mordheim (MOR) Wood Elves Army book (WE) “Unofficial” sources : Rolston's Realm of Sorcery draft (RRoS) A Private War (APW) by Tim Eccles with assistance from Ryan Wileman and MadAlfred The italicised entries are from MadAlfred Imperial Events Year c-1000 Bretonni tribes migrate across the Grey Mountains (BRET). They are forced to do so by the expanding Unberogen tribe. c-500 Rise of Humanity in northern Old World. First dealings with Dwarfs. Establishment of numerous petty states throughout rest of Old World. (WFRP) c -300 to Indigenous Thuringians subjugated by migrating Thurini from the east. (APW) -100 -85 Founding of Reikdorf [Altdorf]. -50 Artur, chief of the Teutognens, discovers the Fauschlag rock. He enlists the aid of a Dwarfen clan to tunnel up through the rock and build a mighty fortress. (M:CoC) -30 Sigmar Heldenhammer born in Reikdorf. (TEW) -20 After his defeat by the Teutognens, Marius receives a vision from Olovald to lead his people from Nordland westward. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth. -

Two Portraits Allegedly Depicting Two Members of the Bosio Family

Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences Research Article Open Access Two portraits allegedly depicting two members of the Bosio family Abstract Volume 3 Issue 4 - 2018 Two portraits of two Hospitaller knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem are Patrice Foutakis often reported as illustrating two members of the Bosio family from Piedmont, Italy. French Ministry of Culture, France Many Bosios have been knights of this Order indeed and these portraits are today at a palace which was the house of Giacomo and Antonio Bosio in the sixteenth and Correspondence: Patrice Foutakis, French Ministry of Culture, seventeenth century. However, no study about these portraits has been carried out so France, Email [email protected] far. A careful examination of the technique, of the style of the painters, of some dress details and the dating of the two paintings, along with biographical data of the Bosios Received: January 09, 2018 | Published: July 26, 2018 members of the Hospitaller Order, reveals that these portraits cannot depict knights from this family. It is neither the first nor the last time that paintings are erroneously identified. Progress in research makes anonymous portraits earning an identity, while unidentified portraits will never get rid of anonymity; nevertheless they deserve credit. Making clear why the two knights on these portraits are not members of the Bosio family is fairly important for the history of art and for the iconographical database. Introduction As part of the rich collection of paintings at the magistral palace, via dei Condotti in Rome (Figure1), there are two portraits, referred as illustrating two members of the Bosio family. -

Maria Stuart (1646)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN THE HUMANIST TRADITION – MARIA STUART (1646) James A. Parente, Jr. and Jan Bloemendal Th e Play, its Subject and its Sources Maria Stuart of Gemartelde Majesteit (Mary Stuart, or Martyred Majesty) was published anonymously in 1646. According to the title page, it was printed ‘in Cologne, at the old printery’ (‘te Keulen, in d’oude druckerye’), which in fact was Vondel’s publisher Abraham de Wees. It was also this printer who paid the poet’s fi ne when he was con- demned to pay one hundred and eighty guilders.1 Th rough the Roman Catholic ‘crucifi ed royal heroine’ and ‘crowned martyr’2 Mary Stuart, who had died some sixty years earlier, Vondel indirectly but unmistak- ably honoured his contemporary King Charles I, and through the fi g- ure of the ambitious Elizabeth I, criticized Cromwell, the leader of Parliament and Charles’s rebellious opponent.3 For the Amsterdam Protestants and the administrators of the Amsterdam Schouwburg, this alignment with the Roman Catholic Queen of Scots was unaccep- table. From their point of view, the play was polemical, blasphemous, and infl ammatory, and they ensured that the court fi ned Vondel for his stance. Th e play was ostentatiously dedicated to Edward, Mary’s only great-grandson and Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, who, like Vondel, had recently converted to Catholicism.4 Vondel also 1 Th e text is published in WB, 5, pp. 162–238. Kristiaan P. Aercke translated the play into English as Mary Stuart, or Tortured Majesty; the translations of Maria Stuart in this chapter are either taken from this translation or based on it. -

Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 06/02/2007 04:11 PM

Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 06/02/2007 04:11 PM Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Sophie Marie Dorothea of Württemberg) Maria Feodorovna (Russian: Мари́я Фёдоровна, 25 October 1759 - 5 November 1828) was the second wife of Tsar Paul I of Russia and mother of Tsar Alexander I and Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. Contents 1 Princess of Württemberg 2 Grand Duchess of Russia 3 Personality 4 European Tour 5 Last Year under Catherine II 6 Empress of Russia 7 Dowager Empress 8 Children 9 Notes 10 Bibliography Maria Feodorovna. Portrait by Alexander Princess of Württemberg Roslin. Maria Feodorovna was born in Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland) on October 25, 1759 as Princess Sophie Marie Dorothea Auguste Louise of Württemberg. She was the daughter of Friedrich II Eugen, Duke of Württemberg and his wife Friederike Dorothea of Brandenburg-Schwedt. Named after her mother, Sophia Dorothea, as she was known in her family, was the eldest daughter of eight children, five boys and three girls. In 1769, when she was ten years old, her family took up residence in the ancestral castle at Montbéliard, near Basel, then in the Duchy of Württemberg, in what is today Alsace.[1] Montbéliard was the seat of the junior branch of the House of Württemberg to which she belonged, it was also a cultural center and many intellectual and political figures frequented her parents' palace . The family's summer residence was situated at Étupes. Princess Sophie’s education was better than average in the culture-oriented paternal home and she would love the arts all her life. -

À / Monsieur / Monsieur Leopold Mozart / Maitre De La Chapelle De / S: A: R: L’Archeveque De / Á / Salzbourg1

0351. MOZART TO HIS FATHER, SALZBURG; POSTSCRIPTS BY HIS COUSIN AND HIMSELF À / Monsieur / Monsieur Leopold Mozart / maitre de la Chapelle de / S: A: R: L’Archeveque de / á / Salzbourg1 Mon trés cher Pére.2 [Augsburg, 17th/16th October,3 1777] 4Concerning that young lady, the daughter of War Secretary Hamm,5 I cannot write anything except that she certainly must have talent for music,6 since she has only been learning for 3 years and yet plays many pieces very well. But I do not know [5] how to express it clearly enough if I am meant to say how she appears to me when she plays; – – – so curiously forced, as it seems to me – – she climbs around the keyboard so curiously with her long-boned fingers. Admittedly, she has not yet had a proper teacher, and if she stays in Munich, she will never in all her days become what her father wishes and demands. [10] For he would much like her to be outstanding on the clavier – – if she comes to Papa in Salzburg, it is of double advantage to her, in her music as well as in her reason, for this is truly not great. I have certainly laughed a lot because of her. You would certainly have enough entertainment for your trouble. She cannot eat much, for she is too simple for that. [15] I should have tested her? – – I was indeed not able to do so for laughing, for when I demonstrated something to her a few times with the right hand, she immediately said bravissimo, and that in the voice of a mouse. -

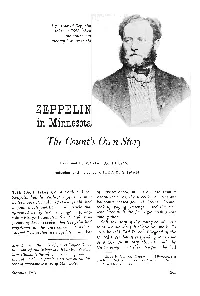

ZEPPELIN in Minnesota the Count's Own Story

A portrait of Zeppelin taken in 1863, when the count was twenty-five years old ZEPPELIN in Minnesota The Count's Own Story Translated by MARIA BACH DUNN Introduction and notes by RHODA R. OILMAN THE FACT THAT Count Ferdinand von of captive ascensions ivere made from a Zeppelin had his earliest experience in a vacant lot across the street by an itinerant balloon over St. Paul in 1863 was established balloonist named John H. Steiner. Steiner beyond much question in an article that took up paying passengers, and the man appeared nearly two years ago in Minne who later built the first rigid airship ivas sota History.^ Research in the St. Paul news among them. papers of 1863 revealed that Zeppelin had Still, the story of the young count's visit registered at the International Hotel on to Minnesota was full of question marks. In August 17, and that two days later a number 1915 he told Karl H. von Wiegand of the United Press that after spending some time as a German military observer with the Mrs. Dunn is the wife of James Taylor Dunn, Union army in northern Virginia, he had librarian of the Minnesota Historical Society. Mrs. Gilman is the editor of this magazine and ' Rhoda R. Gilman, "Zeppelin in Minnesota: A the author of two previous articles on the his Study in Fact and Fable," in Minnesota History, tory of aeronautics in early Minnesota. 39:278-285 (Fall, 1965). Summer 1967 265 decided to see something of the country. water that they had nothing in which to cook He had traveled by steamer on the Great these animals they ate them raw. -

Bavaria the Bavarians Emerged in a Region North of the Alps, Originally Inhabited by the Celts, Which Had Been Part of the Roman Provinces of Rhaetia and Noricum

Bavaria The Bavarians emerged in a region north of the Alps, originally inhabited by the Celts, which had been part of the Roman provinces of Rhaetia and Noricum. The Bavarians spoke Old High German but, unlike other Germanic groups, did not migrate from elsewhere. Rather, they seem to have coalesced out of other groups left behind by Roman withdrawal late in the 5th century AD. These peoples may have included Marcomanni, Thuringians, Goths, Rugians, Heruli, and some remaining Romans. The name "Bavarian" ("Baiuvari") means "Men of Baia" which may indicate Bohemia, the homeland of the Marcomanni. They first appear in written sources circa 520. Saint Boniface completed the people's conversion to Christianity in the early 8th century. Bavaria was, for the most part, unaffected by the Protestant Reformation, and even today, most of it is strongly Roman Catholic. From about 550 to 788, the house of Agilolfing ruled the duchy of Bavaria, ending with Tassilo III who was deposed by Charlemagne. Three early dukes are named in Frankish sources: Garibald I may have been appointed to the office by the Merovingian kings and married the Lombard princess Walderada when the church forbade her to King Chlothar I in 555. Their daughter, Theodelinde, became Queen of the Lombards in northern Italy and Garibald was forced to flee to her when he fell out with his Frankish over- lords. Garibald's successor, Tassilo I, tried unsuccessfully to hold the eastern frontier against the expansion of Slavs and Avars around 600. Tassilo's son Garibald II seems to have achieved a balance of power between 610 and 616.