Gender Representation and Perception in Turn-Of-The-Century Chick Flicks" (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI As of 3/1/2017

University of Northern Colorado School of Theatre Arts and Dance DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI as of 3/1/2017 Broadway – 25 Performers (55 Productions) Josh Buscher – West Side Story 2009 (OC), Pricilla Queen of the Desert (OC), Big Fish (OC) Ryan Dinning – Machinal (OC) Jenny Fellner – Wicked, Mamma Mia, The Boyfriend, Pal Joey (OC) Scott Foster – Forbidden Broadway (Alive and Kicking) 2013, Brooklyn (OC), Forbidden Broadway (Alive and Kicking) 2014 Greg German – Assassins (OC), Biloxi Blues (OC), Boeing/Boeing Patty Goble – Bye Bye Birdie 2009 (OC), Curtains (OC), The Woman in White (OC), La Cage Aux Follies 2004 (OC), Kiss Me Kate 1999 (OC), Ragtime (OC), Phantom of the Opera Derek Hanson – Anything Goes (Sutton Foster), Side Show (2014 Revival), An American in Paris (2016), Tamara Hayden – Les Miz, Cabaret Autumn Hulbert – Legally Blonde Aisha Jackson – Beautiful: The Carol King Musical, Waitress (OC) Ryan Jesse – Jersey Boys Patricia Jones – Buried Child (OC), Indiscretions (w/Kathleen Turner) Andy Kelso – Mamma Mia, Kinky Boots (OC) Beth Malone – Ring of Fire (OC), Fun Home (OC)+ Victoria Matlock – Million Dollar Quartet (OC) Jason Olazabal – Julius Caesar (OC) (w/Denzel Washington) Laura Ryan – Country Roads The John Denver Musical (OC) Lisa Simms – A Chorus Line Andrea Dora Smith – Tarzan, Motown (OC) Erica Sweany – Honeymoon in Vegas – The Musical (OC) Jason Veasey – The Lion King Jason Watson – Mamma Mia Aléna Watters – Sister Act (OC), Adams Family Musical (OC), West Side Story 2009, Wysandria Woolsey – Chess, Parade, Beauty and the -

Withering Heights

Withering Heights When one mentions the Presbyterian Church, the name that first comes to mind is that of the Scottish Calvinist clergyman John Knox. This dynamic religious leader of the Protestant Reformation founded the Presbyterian denomination and was at the beginning of his ministry in Edinburgh when he lost his beloved wife Marjorie Bowes. In 1564 he married again, but the marriage received a great deal of attention. This was because she was remotely connected with the royal family, and Knox was almost three times the age of this young lady of only seventeen years. She was Margaret Stewart, daughter of Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord of Ochiltree. She bore Knox three daughters, of whom Elizabeth became the wife of John Welsh, the famous minister of Ayr. Their daughter Lucy married another clergyman, the Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon. Their descendant, John Knox Witherspoon (son of another Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon), signed the Declaration of Independence on behalf of New Jersey and (in keeping with family tradition) was also a minister, in fact the only minister to sign the historic document. John Knox Witherspoon (1723 – 1794), clergyman, Princeton’s sixth president and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Just like Declaration of Independence signatory John Witherspoon, actress Reese Witherspoon is also descended from Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon and his wife Lucy (and therefore John Knox). The future Academy Award winner, born Laura Jeanne Reese Witherspoon, was born in New Orleans, having made her début appearance at Southern Baptist Hospital on March 22, 1976. New Orleans born Academy Award winning actress, Reese Witherspoon Reese did not get to play Emily Brontë’s Cathy in “Wuthering Heights” but she did portray Becky Sharp in Thackeray’s “Vanity Fair”. -

JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Reida York Director of Advertising and Public Relations 816.559.3847 office | 816.668.9321 cell [email protected] JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series PHOENIX, AZ – The Tony Award®-winning Best Musicals JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series, presented by Theater League in Phoenix, Arizona, at the beautiful Orpheum Theatre. Season renewals and priority orders are available at BroadwayOrpheum.com or by calling 800.776.7469. “We are thrilled to bring such powerful productions to the Orpheum Theatre,” Theater League President Mark Edelman said. “We are honored to be a part of this community and we look forward to contributing to the arts and culture of Phoenix with this strong season.” The Broadway in Thousand Oaks line-up features the best of Broadway, including the international sensation, JERSEY BOYS, the high-heeled hit, KINKY BOOTS, the nostalgic standard, MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT, and the legendary classic, A CHORUS LINE. The 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series includes the following hit musicals: MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT December 1-3, 2017 A Broadway classic in concert featuring the nostalgic score of rousing marches, barbershop quartets and sentimental ballads, which have become popular standards. Meredith Willson’s musical comedy has been delighting audiences since 1957 and is sure to entertain every generation. Harold Hill is a traveling con man, set to pull a fast one on the people of River City, Iowa, by promising to put together a boys band and selling instruments — despite the fact he knows nothing about music. -

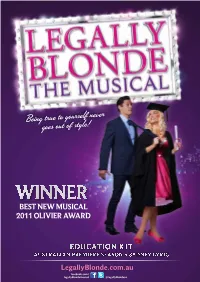

Legally Blonde: Introduction

Being true to yourself never goes out of style! WINNER BEST NEW MUSICAL 2011 OLIVIER AWARD EDUCATION KIT AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE SEASON • SYDNEY LYRIC LegallyBlonde.com.au facebook.com/ legallyblondemusical @legallyblondeoz Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION This teacher’s guide has been developed as a teaching tool to assist teachers who are bringing their students to see the show. This guide is based on Camp Broadway’s StageNOTES, conceived for the original Broadway musical adaptation of Amanda Brown’s 2001 novel and the film released that same year, and has been adapted for use within the UK and Australia. The Australian Education Pack is intended to offer some pathways into the production, and focuses on some of the topics covered in Legally Blonde which may interest students and teachers. It is not an exhaustive analysis of the musical or the production, but instead aims to offer a variety of stimuli for debate, discussion and practical exploration. It is anticipated that the Education Pack will be best utilised after a group of students have seen the production with their teacher, and can engage in an informed discussion based on a sound awareness of the musical. We hope that the information provided here will both enhance the live theatre experience and provide readers with information they may not otherwise have been able to access. Legally Blonde is an uplifting, energising, feel-good show and with that in mind we hope this pack will be enjoyed through equally energising and enjoyable practical work in the classroom and drama studio. 1 Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION LEgally Blonde Education Pack CONTENTS PAGE INTODUCTION 1. -

Critical Theory, Authoritarianism, and the Politics of Lipstick from The

Article 0(0) 1–26 Critical theory, ! The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: authoritarianism, and the sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/2050303218800374 politics of lipstick from journals.sagepub.com/home/crr the Weimar Republic to the contemporary Middle East Janet Afary University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Roger Friedland New York University, USA; University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Abstract In 2012–13, we signed up for Facebook in seven Muslim-majority countries and used Facebook advertisements to encourage young people to participate in our survey. Nearly 18,000 individuals responded. Some of the questions in our survey dealing with attitudes about women’s work and cosmetics were adopted from a survey conducted by the Frankfurt School in 1929 in Germany. The German survey had shown that a great number of men, irrespective of their political affiliation harbored highly authoritarian attitudes toward women and that one sign of authoritarianism was men’s attitude toward cosmetics and women’s employment. We wanted to know if the same was true of the contemporary Middle East. Our results suggest that lipstick and makeups as well as women’s employment are not just vehicles for sexual objectification of women. In the Muslim world a married woman’s desire to work outside the house, and her pursuit of the accoutrement of beauty and sexual attractiveness, are forms of gender politics, of women’s empowerment, but also of antiauthoritarianism and liberal politics. Our results also suggest that piety per se is not an indicator of authoritarianism and that there is a marked gender difference in authoritarianism. -

Director's Notes

DIRECTOR’S NOTES Thoughts on LEGALLY BLONDE The musical Legally Blonde is based on a novel by Amanda Brown and the 2001 film of the same name directed by Robert Luketic. The film was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture: Musical or Comedy and ranks 29th on Bravo’s 2007 list of “100 Funniest Movies.” Premiering on January 23, 2007 in San Francisco, the Broadway musical version of Legally Blonde opened in NYC at the Palace Theatre on April 29, 2007. The show’s stars, Laura Bell Bundy, Christian Borle, and Orfeh were all nominated for Tony Awards. Later, the Broadway show was the focus of an MTV reality TV series called “Legally Blonde – The Musical: The Search for Elle Woods,” in which the winner would take over the role of Elle on Broadway. The Broadway show closed on October 19, 2008 after 595 performances. But even more successful than the Broadway run of Legally Blonde, was a highly lauded 3 year run at the Savoy Theatre in London’s West End, in which the show was nominated for five Laurence Olivier Awards. It won three, including Best New Musical. Since then, Legally Blonde has enjoyed international success in productions seen in South Korea, The Netherlands, France, The Philippines, Sweden, and Finland. Certainly, it is undeniable that both film and musical are pure escapist joy. But Legally Blonde does have a point beyond its camp wondrousness – and that is to challenge the way people make assumptions about appearance. For whether you are a beautiful bubbly blonde (like our heroine, Elle) or someone more “serious” in nature, we all have had to, at one time or another, battle prejudice against ourselves. -

Legally Blonde Cast List

Legally Blonde Cast List Elle Woods………………………………………………………………………………….Kaylie Tuttle/Greer King Emmett Forrester……………………………………...……………………………………………….Jordan Pogue Paulette Bonafonte’………………………………………………………………………..….…..…….Skyler Ward Warner Huntington III…………………..………………………………………………….….……Brittin Sullivan Brooke Wyndham………………………………………………………………………………….………Avery Bruce Professor Callahan…………………………..……………………………………………………….……Sam Gibson Vivienne Kensington……………………………………………………….………………………..Elizabeth Ring Margot………………………………………………………………….……….………….……….Brooklyn Jennings Serena…………………………………………….……………………………………….………………….Natalie Way Pilar…………….………………………………….…..……………………….………Sarah Mitchell/Kelsey Drees Kate…………………………………………………......…….………………………….…………………Nicole Vincent Gaelen…………………………………………..……………………………………………………….Bailey Weathers Tiffany………………………………………..…………………………………………………………………Rainey Ross Courtney…………………………………..……………………………………………………………..Mikee Olegario Sandi…………………………………………..………………………………………………………………..Payton King Angel…………………………………………….………………………….…………………….…………Lizzie Schaefer Enid……………………………………………...……………………………………………………………..Lauren Black Mr. Woods……………………………………..………………………………………………………….David Nichols Mrs. Woods………………………………….……………………..………………………………….Emily Freeman Chutney Wyndham…………………………...………………………………………………………Bethie Butera Kyle……………………………………....……………………………………………………………………Harris Sutton Winthrop………………………………………..………………………………………………………Lane Burchfield Judge……………………………………………………………………………………….……….Autumne Kendricks Grandmaster Chad…………………………………………………………………..……………………..DJ Boswell Dewey……………………………………………………..…….………………………..Easton -

The Music of Frank Zappa MUGC 4890-001 • MUGC 5890-001 Dr

The Music of Frank Zappa MUGC 4890-001 • MUGC 5890-001 Dr. Joseph Klein" III. Social and Cultural Context" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Post-War Period " Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Family and Lifestyle" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Cold War & “Red Menace”" Cultural Context — 1940s & 50s: Cold War & “Red Menace”" Cultural Context — 1950s: B Movies" Cultural Context — 1950s: B Movies" “Zombie Woof”! “Cheepnis”! “The Radio is Broken”! Overnite Sensation ! (1973)! ! Roxy & Elsewhere ! (1974)! The Man From Utopia ! (1983)! Cultural Context — 1960s: Civil Rights Movement" Cultural Context — 1960s: Great Society, Viet Nam War" Cultural Context — 1960s: Hippie Culture & Flower Power" Cultural Context — 1970s: Watergate, Recession" Cultural Context — 1970s: Disco Era" Cultural Context — 1990s: Collapse of the Soviet Union" Archetypes in the Project/Object" § Suzy Creamcheese" §! Hippies" §! Plastic People" §! Pachucos" §! Lonesome Cowboy Burt" §! Bobby Brown" §! Jewish American Princess" §! Catholic Girls" §! Valley Girl" §! Charlie (“kinda young, kinda wow…”)" §! Debbie" §! Thing-Fish (composite archetypes)" “Who Needs the Peace Corps?” (We’re Only In It for the Money, 1968)" I'll stay a week and get the crabs and! Take a bus back home! I'm really just a phony! But forgive me! 'Cause I'm stoned Every town must have a place! Where phony hippies meet! Psychedelic dungeons! Popping up on every street! GO TO SAN FRANCISCO . How I love ya, How I love ya! How I love ya, How I love ya Frisco!! How I love ya, How I love ya! What's there to live for?! How I love ya, How I love ya! Who needs the peace corps?! Oh, my hair is getting good in the back! Think I'll just DROP OUT! Every town must have a place! I'll go to Frisco! Where phony hippies meet! Buy a wig & sleep! Psychedelic dungeons! On Owsley's floor Popping up on every street ! Walked past the wig store! GO TO SAN FRANCISCO . -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

Legally Blonde

Legally Blonde Elle Woods; A feminist in a pink dress? What’s the story? Elle Woods • Superficial • Popular • Blonde Get’s dumped by her boyfriend who wants a serious girlfriend What’s the story? • So, she applies to Harvard Law School • Somehow, she gets in! • Her ex, Warner, has a new girlfriend. • After meeting Emmett, Elle realises she has to prove herself. What’s the story? • She is awarded a top Court Case • She then finds out it was only because her mentor, Callaghan, found her attractive and he sexually harasses her. • But, through her determination and honesty, she wins the case. What’s the story? • In the end, she marries Emmett • She helps many friends along the way • And proves that blondes can be intelligent. STEREOTYPES Culture defined by stereotypes • Elle has a clear stereotype • She manages to disprove it… • …whilst retaining her ‘look’. Elle the Elle the Elle the fashion- Blonde Intelligent conscious Stereotypes Prejudice • Stereotypes often play a big role in prejudice • Historically, America has a big issue with prejudice Racism • Even today, there are problems. FEMINISM TRADITIONAL FEMINISM ELLE’S FEMINISM About finding equality with men by Using skills that are viewed as ‘feminine’ rejecting ‘femininity’. to her advantage and embracing her Proving that women can do exactly the ‘femininity. same things as men. Accepts that men and women are different but equal in their own right. How does the film show this? • Elle solves a case that no man can, because of her knowledge of hair care. • Warner and Callaghan both are portrayed as disloyal and only really interested in sex. -

EMU Today, April 13, 2015 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU EMU Today EMU Today 2015 EMU Today, April 13, 2015 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today Recommended Citation "EMU Today, April 13, 2015." Eastern Michigan University Division of Communications. EMU Archives, Digital Commons @ EMU (http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today/640). This University Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the EMU Today at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in EMU Today by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On this day...In 1997, 21-year-old Tiger Woods wins the prestigious Masters Tournament by a record 12 strokes in Augusta, Georgia. It was Woods’ first victory in one of golf’s four major championships–the U.S. Open, the British Open, the PGA Championship, and the Masters–and the greatest performance by a professional golfer in more than a century. Quote: "When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world." - George Washington Carver Fact: Apollo 13 was the seventh manned mission in the American Apollo space program and the third intended to land on the Moon. The craft was launched on April 11, 1970, from the Kennedy Space Center, but the lunar landing was aborted after an oxygen tank exploded two days later, crippling the Service Module (SM) upon which the Command Module (CM) depended. Despite great hardship caused by limited power, loss of cabin heat, shortage of potable water, and the critical need to jury-rig the carbon dioxide removal system, the crew returned safely to Earth on April 17. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director.