Defibrillation During Resuscitation (1995)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Access Defibrillation/AED Program Implementation Guide

Public Access Defibrillation/AED Program Implementation Guide There are 4 key elements to establishing a Public Access Defibrillation program. These include: Having designated rescuers trained in CPR and in how to use an automated external defibrillator (AED) Having a physician to provide medical oversight and direction Integrating your program with the local emergency medical services (EMS) system Using and maintaining the AED(s) according to the manufacturers specifications Steps: 1. Gain consensus Within your company or organization begin to identify the key decision makers and arrange a meeting to gain support. The American Heart Association or your local EMS Agency can assist you with presentation materials. 2. Review the law and regulations Review Federal, State and local laws and regulations regarding Public Access Defibrillation program requirements. Consult your local Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Agency The California laws ang regulations that pertain to AEDs are Title 22, and AB 658. 3. Consult your local Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Agency The local EMS Agency can provide you with information regarding training, purchasing AEDs, medical direction and laws and regulations. 4. Identify your response team Identify who would be most likely to respond in an emergency – this will help determine how and where AEDs are mounted or stored. 5. Select equipment and vendor Some considerations in selecting the AED may include: Reputation of the AED manufacturer for the product’s quality and customer service, compatibility with the equipment used in the local EMS system, and ease of operation of the AED. 6. Design Policies and Procedures These may include: Who manages the AED program When the AED should be used, when it should not be used Training required to use the AED Locations of AEDs and other equipment (such as gloves and pocket mask for CPR) Notification process for internal AED responders and external emergency medical services responders Maintenance schedule for equipment Training and refresher training policies 7. -

Basic Life Support + First Aid for Healthcare Providers 2020 Course Introduction

Basic Life Support + First Aid for Healthcare Providers 2020 Course Introduction SECTION 1: Foundational concepts of BCLS SECTION 2: Response to an adult in cardiac arrest SECTION 3: Basic Life Support for infants and children SECTION 4: Automated external defibrillation in infants and children SECTION 5: Preventing cardiac arrest SECTION 6: First aid for adults SECTION 7: First aid for children Activity Summary • Activity Title: Basic Life Support (BLS) & First Aid (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), Automated External Defibrillator (AED), and First Aid) • Release date: 2021-06-01 • Expiration date: 2024-06-01 • Estimated time to complete activity: 8 hours • This course is accessible with any web browser. We recommend recent versions of • Google Chrome, Internet Explorer 9 and later, or Apple iPad. • This course is jointly provided by Pacific Medical Training and Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM). You may reach PIM at [email protected]. Target Audience This activity has been designed to meet the educational needs of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, pharmacists and dentists involved in the care of patients who require advanced life support. 3103 Philmont Ave, Suite 308 • Huntingdon Valley, PA 19006 • 800-417-1748 page 1 Educational Objectives After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to: • Explain the change in emphasis from airway and ventilation to compressions and perfusion. • Select the correct order of interventions for the victim of cardiopulmonary arrest. • List the steps required to safely operate an AED. • Differentiate between adult and pediatric guidelines for CPR. • Explain how to apply the various first aid interventions. • Describe how to apply the various pediatric first aid interventions. -

Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality 1

Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality 1 Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality Web-based Integrated 2010 & 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Key Words: cardiac arrest cardiopulmonary resuscitation defibrillation emergency 1 Highlights & Introduction 1.1 Highlights: Lay Rescuer CPR Summary of Key Issues and Major Changes Key issues and major changes in the 2015 Guidelines Update recommendations for adult CPR by lay rescuers include the following: The crucial links in the out-of-hospital adult Chain of Survival are unchanged from 2010, with continued emphasis on the simplified universal Adult Basic Life Support (BLS) Algorithm. The Adult BLS Algorithm has been modified to reflect the fact that rescuers can activate an emergency response (ie, through use of a mobile telephone) without leaving the victim’s side. It is recommended that communities with people at risk for cardiac arrest implement PAD programs. Recommendations have been strengthened to encourage immediate recognition of unresponsiveness, activation of the emergency response system, and initiation of CPR if the lay rescuer finds an unresponsive victim is not breathing or not breathing normally (eg, gasping). Emphasis has been increased about the rapid identification of potential cardiac arrest by dispatchers, with immediate provision of CPR instructions to the caller (ie, dispatch-guided CPR). The recommended sequence for a single rescuer has been confirmed: the single rescuer is to initiate chest compressions before giving rescue breaths (C-A-B rather than A-B-C) to reduce delay to first compression. The single rescuer should begin CPR with 30 chest compressions followed by 2 breaths. -

Delaying Defibrillation to Give Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation to Patients with Out-Of-Hospital Ventricular Fibrillation a Randomized Trial

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Delaying Defibrillation to Give Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation to Patients With Out-of-Hospital Ventricular Fibrillation A Randomized Trial Lars Wik, MD, PhD Context Defibrillation as soon as possible is standard treatment for patients with ven- Trond Boye Hansen tricular fibrillation. A nonrandomized study indicates that after a few minutes of ven- Frode Fylling tricular fibrillation, delaying defibrillation to give cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) first might improve the outcome. Thorbjørn Steen, MD Objective To determine the effects of CPR before defibrillation on outcome in pa- Per Vaagenes, MD, PhD tients with ventricular fibrillation and with response times either up to or longer than Bjørn H. Auestad, PhD 5 minutes. Design, Setting, and Patients Randomized trial of 200 patients with out-of- Petter Andreas Steen, MD, PhD hospital ventricular fibrillation in Oslo, Norway, between June 1998 and May 2001. ARLY DEFIBRILLATION IS CRITICAL Patients received either standard care with immediate defibrillation (n=96) or CPR first for survival from ventricular fi- with 3 minutes of basic CPR by ambulance personnel prior to defibrillation (n=104). If initial defibrillation was unsuccessful, the standard group received 1 minute of CPR brillation. The survival rate de- before additional defibrillation attempts compared with 3 minutes in the CPR first group. creases by 3% to 4% or 6% to E10% per minute depending on whether Main Outcome Measure Primary end point was survival to hospital discharge. Sec- ondary end points were hospital admission with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation 1,2 1-year survival, and neurological outcome. A prespecified analysis examined sub- (CPR) is performed. -

The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: a Review of the Current Treatment

1/24/2018 The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: A Review of the Current Treatment Options Marc Conterato, MD, FACEP Office of the Medical Director North Memorial Health Ambulance Service DISCLOSURE STATEMENT • Board Member, MN Resuscitation Consortium - Images of any commercial devices or medications are for illustration purposes only. The inclusion of such images in this presentation does not imply endorsement of any specific device or company. 2 Objectives • Delineate Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation (RVF) • Recurrent VF versus Refractory VF • What is “Electrical Storm” • Current Pre-hospital treatments • Additional hospital treatments • Dual/Double Sequential Defibrillation • ECMO/ECLS-A New Hope? 3 1 1/24/2018 A Standard Scenario • 55 YOF collapses at stop light, and her car rolls into the car in front of her. Airbags do not deploy, and bystanders find her slumped over the steering wheel and pulseless. • First responder/bystanders start CPR, and deliver three AED shocks prior to EMS arrival. • On EMS arrival, a fourth shock is delivered, an IO and alternative airway placed. Automated CPR started. • Epinephrine 2 mg (total) and Amiodarone 300 mg given, and the patient remains in VF. • Patient downtime is now ~25 minutes, and repeat evaluation reveals persistent VF. 4 What are your options • Continue CPR for a total of 30 minutes with recurrent defibrillations, additional epinephrine, bicarbonate and Amiodarone? • “Load and Go” to the local hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation? • “Load and Go” to the local CCL (Cardiac Cath Lab) hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, with possible PCI with ongoing CPR? • Call HEMS unit for transfer to CCL hospital, but can they continue effective CPR in the helicopter? • “Load and Go” to a ECMO/ECLS center with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, on the basis they can accept the patient and continue resuscitation? 5 Defining the problem: What is recurrent versus refractory VF (RVF)? • Recurrent VF is a rhythm that terminates with cardioversion, but then recurs rapidly. -

Goals of Care and End of Life in the ICU

Goals of Care and End of Life in the ICU Ana Berlin, MD, MPH, FACS KEYWORDS Goals of care Shared decision making ICU Functional and cognitive outcomes End-of-life care Palliative care Communication KEY POINTS The trauma and long-term sequelae of critical illness affect not only patients but also their families and caregivers. Unrealistic expectations and erroneous assumptions about the outcomes acceptable to patients are important drivers of misguided and goal-discordant medical treatment. Compassionately delivering accurate and honest prognostic information inclusive of func- tional, cognitive, and psychosocial outcomes is crucial for helping patients and families understand what to expect from an episode of surgical crticial illness. Skilled communication and shared decision-making strategies ensure that treatments provided in the ICU are aligned with realistic and attainable patient goals. Attentive management of physical and nonphysical symptoms, including the psychosocial and spiritual needs of families and caregivers, eases suffering in the ICU and beyond. INTRODUCTION There is little doubt that the past half-century has seen tremendous advances in surgical critical care. The advent of lung-protective ventilation in the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the evolution of balanced resusci- tation strategies for the reduction of abdominal compartment syndrome, and the aggressive deployment of prevention and treatment strategies against the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis, along with many other technological innovations, have markedly reduced the morbidity and mortality associated with critical illness and multiorgan system failure. Nevertheless, at times even the Disclosure Statement: Support for Dr A. Berlin’s preparation of this article was provided by the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources and Services Administration through Grant D34HP26020. -

Resuscitation and Defibrillation

AARC GUIDELINE: RESUSCITATION AND DEFIBRILLATION AARC Clinical Practice Guideline Resuscitation and Defibrillation in the Health Care Setting— 2004 Revision & Update RAD 1.0 PROCEDURE: signs, level of consciousness, and blood gas val- Recognition of signs suggesting the possibility ues—included in those conditions are or the presence of cardiopulmonary arrest, initia- 4.1 Airway obstruction—partial or complete tion of resuscitation, and therapeutic use of de- 4.2 Acute myocardial infarction with cardio- fibrillation in adults. dynamic instability 4.3 Life-threatening dysrhythmias RAD 2.0 DESCRIPTION/DEFINITION: 4.4 Hypovolemic shock Resuscitation in the health care setting for the 4.5 Severe infections purpose of this guideline encompasses all care 4.6 Spinal cord or head injury necessary to deal with sudden and often life- 4.7 Drug overdose threatening events affecting the cardiopul- 4.8 Pulmonary edema monary system, and involves the identification, 4.9 Anaphylaxis assessment, and treatment of patients in danger 4.10 Pulmonary embolus of or in frank arrest, including the high-risk de- 4.11 Smoke inhalation livery patient. This includes (1) alerting the re- 4.12 Defibrillation is indicated when cardiac suscitation team and the managing physician; (2) arrest results in or is due to ventricular fibril- using adjunctive equipment and special tech- lation.1-5 niques for establishing, maintaining, and moni- 4.13 Pulseless ventricular tachycardia toring effective ventilation and circulation; (3) monitoring the electrocardiograph and recogniz- -

The Transthoracic Impedance Cardiogram Is a Potential Haemodynamic Sensor for an Automated External Defibrillator

European Heart Journal (1998) 19, 1879–1888 Article No. hj981199 The transthoracic impedance cardiogram is a potential haemodynamic sensor for an automated external defibrillator P. W. Johnston*, Z. Imam†, G. Dempsey†, J. Anderson† and A. A. J. Adgey *Regional Medical Cardiology Centre, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast; †Northern Ireland Bioengineering Centre, Belfast, Northern Ireland Aims The American Heart Association has endorsed the agonal rhythm (20), electromechanical dissociation (22), concept of Public Access Defibrillation. However, there ventricular tachycardia (27) and sinus rhythm (5). These have been reports of inappropriate direct current shocks rhythms were divided into those associated with haemo- from automatic external defibrillators. The specificity of dynamic collapse i.e. no pulse — asystole, ventricular fibril- automatic external defibrillators for shockable rhythms lation, agonal rhythm, electromechanical dissociation and may be improved by the incorporation of a haemodynamic shockable ventricular tachycardia (associated with loss of sensor. consciousness, pulselessness or a systolic blood pressure of <80 mmHg) (Group 1) and those associated with a satis- Methods and Results This study examined the use of four factory cardiac output i.e. non-shockable ventricular tachy- parameters extracted from the impedance cardiogram i.e. cardia (conscious with a pulse) and sinus rhythm (Group 2). Peak dz/dt (the peak of the impedance cardiogram On univariate analysis each of the four impedance cardio- measured from the line dz/dt=0 Ùs"1), Peak-trough (the gram parameters were significantly greater in Group 2 than peak-to-trough measurement of the impedance cardiogram Group 1 (P<0·001). On multivariate analysis the par- Ùs"1), Area 1 (the area under the C wave of the impedance ameters which best differentiated the two groups were Area cardiogram above the line dz/dt=0 mÙ) and Area 2 (the 1 and Peak-trough. -

PUBLIC ACCESS to AUTOMATED EXTERNAL DEFIBRILLATORS (Aeds) FACTS

POSITION STATEMENT PUBLIC ACCESS TO AUTOMATED EXTERNAL DEFIBRILLATORS (AEDs) FACTS • Cardiac refers to the heart. Arrest means stop. Sudden cardiac arrest is the sudden and unexpected loss of heart function. • Signs of cardiac arrest include: no breathing or only gasping, no movement, and no pulse. • Up to 40,000 cardiac arrests occur each year in Canada. That’s one cardiac arrest every 12 minutes. Without rapid and appropriate treatment, most of these cardiac arrests will result in death. Thousands of lives could be saved through public access to automated external defibrillators. • An automated external defibrillator (AED) is a small, portable device used to identify cardiac rhythms and deliver a shock to correct abnormal electrical activity in the heart. As a result of the sophisticated electronics in an AED the operator will only be advised to deliver a shock if the • A landmark study of the City of Chicago airports public heart is in a rhythm which can be corrected by defibrillation. access to AED program showed survival rates as high as If a shockable rhythm is not detected, no shock can be 75%. This success is directly related to highly visible, readily given and the provider will be instructed to perform accessible automated external defibrillators for public use cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) until emergency and an integrated structured emergency response system.7 medical services arrive. • Research shows that AEDs are most effectively used by • When an AED and CPR are immediately available, the trained individuals. However, AEDs are safe and easy to use chance of survival from sudden cardiac arrest is substantially by almost anyone. -

Sudden Cardiac Arrest a Treatable Public Health Crisis Ê Ê

Sudden Cardiac Arrest A Treatable Public Health Crisis Table of Contents Overview Part I: Medical Issues Definition and Incidence of Sudden Cardiac Arrest Treatment of Sudden Cardiac Arrest The Evolution of Rapid Emergency Defibrillation Part II: Economic Issues Part III: Technology Issues The Automatic External Defibrillator (AED) Breakthrough AED Technology: Key Criteria Part IV: The Ultimate Goal—Rapid And Effective Response Summary and Conclusions Glossary References "Sudden Cardiac Arrest: A Treatable Public Health Crisis" was written under an educational grant from Heartstream, Inc. by Communicore, an independent medical communications organization. It is one White Paper in a series published by Communicore to explore emerging issues in healthcare, generate awareness about these topics, and facilitate discussion about possible solutions. For more information about this or any other Communicore product or service e-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © 1996, Communicore, 2 Union Square, 601 Union Street, Suite 4600, Seattle, WA 98101 USA. Any reproduction without permission is prohibited. Overview Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) remains a major unresolved public health problem; each year in the United States alone, sudden cardiac arrest strikes more than 350,000 people—nearly 1,000 per day—making it the single leading cause of death.1,2 Due in part to the unexpectedness with which SCA strikes, most of these victims die before reaching a hospital. Currently, the chances of surviving an SCA in the United States are less than one in 20. Experts agree that many of the deaths due to SCA are preventable and that available technology, if appropriately applied, could reduce them significantly at a relatively low cost.3 The vast majority of sudden cardiac arrests are due to abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias, of which ventricular fibrillation is the most common. -

Recommendations for End-Of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit: a Consensus Statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine

Special Articles Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine Robert D. Truog, MD, MA; Margaret L. Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN; J. Randall Curtis, MD, MPH; Curtis E. Haas, PharmD, FCCP; John M. Luce, MD; Gordon D. Rubenfeld, MD, MSc; Cynda Hylton Rushton, PhD, RN, FAAN; David C. Kaufman, MD Background: These recommendations have been developed to to die, and between consequences that are intended vs. those that improve the care of intensive care unit (ICU) patients during the are merely foreseen (the doctrine of double effect). Improved dying process. The recommendations build on those published in communication with the family has been shown to improve pa- 2003 and highlight recent developments in the field from a U.S. tient care and family outcomes. Other knowledge unique to end- perspective. They do not use an evidence grading system because of-life care includes principles for notifying families of a patient’s most of the recommendations are based on ethical and legal death and compassionate approaches to discussing options for principles that are not derived from empirically based evidence. organ donation. End-of-life care continues even after the death of Principal Findings: Family-centered care, which emphasizes the patient, and ICUs should consider developing comprehensive the importance of the social structure within which patients are bereavement programs to support both families and the needs of embedded, has emerged as a comprehensive ideal for managing the clinical staff. Finally, a comprehensive agenda for improving end-of-life care in the ICU. -

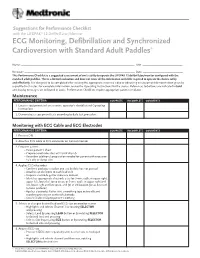

ECG Monitoring, Defibrillation and Synchronized Cardioversion with Standard Adult Paddles*

Suggestions for Performance Checklist with the LIFEPAK® 12 Defibrillator/Monitor ECG Monitoring, Defibrillation and Synchronized Cardioversion with Standard Adult Paddles* Name: _____________________________________________________________________________ Unit: ______________________________ Reviewer: ___________________________________________________________________________ Date: ______________________________ This Performance Checklist is a suggested assessment of one’s ability to operate the LIFEPAK 12 defibrillator/monitor configured with the standard adult paddles. This is a limited evaluation and does not cover all the information and skills required to operate the device safely and effectively. It is designed to be completed after viewing the appropriate inservice video or observing an equipment demonstration given by a qualified instructor. For complete information, review the Operating Instructions for the device. References to buttons are indicated in bold and display messages are indicated in italics. Performance Checklists require appropriate patient simulator. Maintenance PERFORMANCE CRITERIA COMPLETE INCOMPLETE COMMENTS 1. Locates equipment and accessories, operator’s checklist and Operating Instructions 2. Demonstrates equipment tests according to daily test procedure Monitoring with ECG Cable and ECG Electrodes PERFORMANCE CRITERIA COMPLETE INCOMPLETE COMMENTS 1. Presses ON 2. Attaches ECG cable to ECG connector on front of monitor 3. Prepares patient • Bares patient’s chest • Prepares electrode sites with brisk dry rub