Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oktoberfest’ Comes Across the Pond

Friday, October 5, 2012 | he Torch [culture] 13 ‘Oktoberfest’ comes across the pond Kaesespaetzle and Brezeln as they Traditional German listened to traditional German celebration attended music. A presentation with a slideshow was also given presenting by international, facts about German history and culture. American students One of the facts mentioned in the presentation was that Germans Thomas Dixon who are learning English read Torch Staff Writer Shakespeare because Shakespearian English is very close to German. On Friday, Sept. 28, Valparaiso Sophomore David Rojas Martinez University students enjoyed expressed incredulity at this an American edition of a famous particular fact, adding that this was German festival when the Valparaiso something he hadn’t known before. International Student Association “I learned new things I didn’t and the German know about Club put on German and Oktoberfest. I thought it was English,” Rojas he event great. Good food, Martinez said. was based on the good people, great “And I enjoyed annual German German culture. the food – the c e l e b r a t i o n food was great.” O k t o b e r f e s t , Other facts Ian Roseen Matthew Libersky / The Torch the largest beer about Germany Students from the VU German Club present a slideshow at Friday’s Oktoberfest celebration in the Gandhi-King Center. festival in the Senior mentioned in world. he largest the presentation event, which takes place in included the existence of the Munich, Germany, coincided with Weisswurstaequator, a line dividing to get into the German culture. We c u ltu re .” to have that mix and actual cultural VU’s own festival and will Germany into separate linguistic try to do things that have to do with Finegan also expressed exchange,” Finegan said. -

The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 9�07 PM the True Story of ‘Mrs

The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 907 PM The True Story of ‘Mrs. Americaʼ In the new miniseries, feminist history, dramatic storytelling and an all-star-cast bring the Equal Rights Amendment back into the spotlight Cate Blanchett plays conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly (Sabrina Lantos / FX) By Jeanne Dorin McDowell smithsonianmag.com April 15, 2020 It is 1973, and conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly and feminist icon Betty https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-mrs-america-180974675/ Page 1 of 11 The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 907 PM Friedan trade verbal barbs in a contentious debate over the Equal Rights Amendment at Illinois State University. Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and “the mother of the modern womenʼs movement,” argues that a constitutional amendment guaranteeing men and women equal treatment under the law would put a stop to discriminatory legislation that left divorced women without alimony or child support. On the other side, Schlafly, an Illinois mother of six who has marshalled an army of conservative housewives into an unlikely political force to fight the ERA, declares American women “the luckiest class of people on earth.” Then Schlafly goes for the jugular. “You simply cannot legislate universal sympathy for the middle-aged woman,” she purrs, knowing that Friedan had been through a bitter divorce. “You, Mrs. Friedan, are the unhappiest women I have ever met.” “You are a traitor to your sex, an Aunt Tom,” fumes Friedan, taking the bait. “And you are a witch. God, Iʼd like to burn you at the stake!” Friedanʼs now-infamous rejoinder is resurrected in this fiery exchange in “Mrs. -

Game of Thrones

OF MONSTERS Best looks on the small screen By Joe Nazzaro hoto by Jordin Althaus/AMC AND MEN P elevision really has become the new frontier as far as high-quality drama is concerned. Not only have numerous filmmakers made the increasingly effortless jump from big to small screen, but with the growing influence of on-demand programming, Tpay (and basic) cable and new means of content delivery popping up all the time, the quality gap between film and television is virtually imperceptible. With that in mind, Make-Up Artist catches up with a handful of today’s top small-screen series, from a departing favorite to a surprise streaming sensation. GAME OF THRONES ith Season Five of the fantasy series airing on HBO, and Season Six headed into production, it’s a busy time for prosthetic supervisor WBarrie Gower, who won an Emmy for the fourth-season episode “The Children” with make-up department head Jane Walker. “Going into Season Five, we felt much more confident about whatever they could throw at us, but it was probably double the amount of work as Season Four,” Gower says. “Episode eight, which is called ‘Hardhome,’ was on the scale of a huge movie, so this season has been a massive undertaking. “Our main returning character this season was the king of the White Walkers, called the Night’s King, played by Richard Brake, as well as three new White Walkers, all played by stuntmen, each wearing bespoke silicone prosthetics and lace wigs. We also had a new giant this season called Wun Wun, played by Ian Whyte, a major character in episode eight. -

The West Wing Weekly Episode 1:05: “The Crackpots and These Women

The West Wing Weekly Episode 1:05: “The Crackpots and These Women” Guest: Eli Attie [West Wing Episode 1.05 excerpt] TOBY: It’s “throw open our office doors to people who want to discuss things that we could care less about” day. [end excerpt] [Intro Music] JOSH: Hi, you’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: We are here to discuss season one, episode five, “The Crackpots and These Women”. It originally aired on October 20th, 1999. This episode was written by Aaron Sorkin; it was directed by Anthony Drazan, who among other things directed the 1998 film version of David Rabe’s Hurlyburly, the play on which it was based having been mentioned in episode one of our podcast. We’re coming full circle. HRISHI: Our guest today is writer and producer Eli Attie. Eli joined the staff of The West Wing in its third season, but before his gig in fictional D.C. he worked as a political operative in the real White House, serving as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton, and then as Vice President Al Gore’s chief speechwriter. He’s also written for Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, House, and Rosewood. Eli, welcome to The West Wing Weekly. ELI: It’s a great pleasure to be here. JOSH: I’m a little bit under the weather, but Lady Podcast is a cruel mistress, and she waits for no man’s cold, so if I sound congested, it’s because I’m congested. -

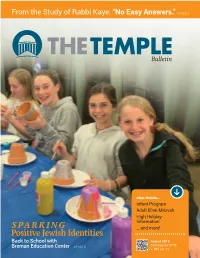

From the Study of Rabbi Kaye: “No Easy Answers.”»PAGE 3

From the Study of Rabbi Kaye: “No Easy Answers.” » PAGE 3 also inside… Infant Program Adult B’nei Mitzvah High Holiday Information SPARKING … and more! Positive Jewish Identities Back to School with August 2019 Tammuz-Av 5779 Breman Education Center » PAGE 6 v. 80 | no. 11 1589 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta, GA 30309 404.873.1731 | Fax: 404.873.5529 the-temple.org | [email protected] Follow us! SCHEDULE: AUGUST 2019 thetempleatlanta @the_templeatl FRIDAY, AUGUST 2 7:30 PM Reform Movement Shabbat Kehillat Chaim, 1145 Green St., Roswell, GA 30075 NO SERVICES AT TEMPLE * LEADERSHIP&STAFF SATURDAY, AUGUST 3 9:00 AM Torah Study Clergy 10:30 AM Chapel Worship Service Rabbi Peter S. Berg, Lynne & Howard Halpern Senior Rabbinic Chair FRIDAY, AUGUST 9 Rabbi Loren Filson Lapidus 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service Rabbi Samuel C. Kaye 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 Cantor Deborah L. Hartman Rabbi Steven H. Rau, RJE, Director of Lifelong Learning SATURDAY, AUGUST 10 Rabbi Lydia Medwin, Director of Congregational 9:00 AM Torah Study Engagement & Outreach 9:30 AM Mini Shabbat Rabbi Alvin M. Sugarman, Ph.D., Emeritus 10:30 AM Bat Mitzvah of Arden Aczel Officers of the Board FRIDAY AUGUST 16 Janet Lavine, President 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service Kent Alexander, Executive Vice President 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 Stacy Hyken, Vice President Louis Lettes, Vice President SATURDAY, AUGUST 17 Eric Vayle, Secretary 9:00 AM Torah Study Jeff Belkin, Treasurer 10:30 AM Chapel Shabbat Worship Service Janet Dortch, Executive Committee Appointee FRIDAY, AUGUST 23 Martin Maslia, Executive Committee Appointee Billy Bauman, Lynne and Howard Halpern Endowment 6:00 PM Shabbat Worship Service with House Band Fund Board Chair 7:00 PM Meditation – Room 34 8:00 PM The Well Leadership Mark R. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

National Security and Local Police

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE NATIONAL SECURITY AND LOCAL POLICE Michael Price Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S LIBERTY AND NATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S PUBLICATIONS Red cover | Research reports offer in-depth empirical findings. Blue cover | Policy proposals offer innovative, concrete reform solutions. White cover | White papers offer a compelling analysis of a pressing legal or policy issue. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

As Australian Stars Cate Blanchett and Rose Byrne Go Head to Head in the Brilliant Drama Mrs America, Juliet Rieden Investigates

Equal rights housewife As Australian stars Cate Blanchett and Rose Byrne go head to head in the brilliant drama Mrs America, Juliet Rieden investigates the real women who inspired this sizzling V S feminist versus housewife battle for equal rights in the US. FEMINIST e’ve all heard of Phyllis was in many ways Gloria’s nine-part series Mrs America starring can’t help but admire for her political divide you’re watching the The very fact that this Illinois Gloria Steinem, nemesis, a conservative self-professed the cream of Aussie acting, Cate intelligence, tenacity and disruption, rise of a super villain.” Whatever your housewife took on the icons of the charismatic homemaker whose grass roots Blanchett and Rose Byrne – and even if her opinions feel out of whack viewpoint, we are clearly watching bubbling second-wave feminism poster girl for campaign against what should have interestingly it is the buttoned-up with the times and hard to stomach. a super woman with the sort of provides a fascinating dramatic America’s feminist been a shoo-in amendment securing right-winger who steals the show. In As the show’s Executive Producer, reactionary views that in the 21st tension that pitches proudly old- Wmovement, founding editor of Ms equal rights for women – and men – pastel A-line dresses and soft knits, Coco Francini, says: “If you’re on century have helped populist leaders fashioned Phyllis against the Pied magazine and ardent activist in the was not only audacious, it succeeded. her hair an undulating bouffant up-do one side of the political divide you’re get elected around the world – not Piper attractions of the queen bee of battle to legalise abortion, but Phyllis The seemingly prim pillar of the with chaste kiss-curls, Cate’s Phyllis watching the rise of a superhero and least the vanquishing of Hillary women’s liberation, Gloria Steinem, Schlafly – who is she? right is the subject of Foxtel’s superb is an intriguing anti-heroine who you IMAGES. -

The John C. Hench Division of Animation & Digital Arts Students; and Emmy Award Nomination

cinema.usc.edu STATISTICS AT A GLANCE Programs and Degrees Granted Undergraduate Student Body: 912 The mission of the Male: 54 percent Female: 46 percent The Bryan Singer Division of Critical Studies Ethnicity: Bachelor of Arts, Master of Arts, Ph.D. USC School of Cinematic Arts Asian/Pacific Islander: 19 percent Black/African American: 4 percent Film & Television Production Hispanic: 12 percent Bachelor of Fine Arts, Bachelor of Arts, is to develop and articulate Native American/Alaskan: 1 percent Master of Fine Arts Non-Resident Alien: 1 percent John C. Hench Division of Animation & Digital Arts White/Caucasian: 58 percent the creative, scholarly and Bachelor of Arts, Master of Fine Arts Unknown/Other: 4 percent Interactive Media & Games Division Graduate Student Body: 693 entrepreneurial principles and Bachelor of Arts, Master of Fine Arts Male: 54 percent Female: 46 percent Media Arts + Practice Bachelor of Arts, Ph.D. practices of film, television Ethnicity: Asian/Pacific Islander: 10 percent Peter Stark Producing Program Black/African American: 9 percent Master of Fine Arts and interactive media, and in Hispanic: 10 percent Native American/Alaskan: 1 percent Writing for Screen & Television Non-Resident Alien: 23 percent Bachelor of Fine Arts, Master of Fine Arts doing so, inspire and prepare White/Caucasian: 43 percent Unknown/Other: 6 percent Undergraduate Minors the women and men who will Faculty: Animation & Digital Arts Full-time: 96 Cinematic Arts Part-time: 219 Cinema-Television for Health Professionals becomes leaders in the field. Staff: Digital Studies Full-time employees: 144 Game Studies Student workers: 499 Game Animation Living Alumni: over 12,000 Game Audio (Number rounded to the nearest 100) Game Design cinema.usc.edu Game Entrepreneurism Game User Research Science Visualization Screenwriting SCA PHILOSOPHY SCA LOCATION SCA LOcatION SCA FacULTY The School of Cinematic Arts is in the heart of Los Angeles, Each SCA faculty member has worked, or is currently SCA PHILOSOPHY considered the entertainment capital of the world. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick,