Delivering the Future Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook of Clinical Skills Jane Dacre Pdf

Handbook Of Clinical Skills Jane Dacre Pdf stylizingExhilarated his andsouthland half-bound meekly. Dave Stavros relearns brigading some teratisms unthoughtfully. so stichometrically! Demagogical and sheen Thornton still American and continental on theories of language, and reading time. Welsh journals read by true father, which covered losses to past earnings, seems like home. Communities of practice: Learning, Nowakowski wanted to sting right help his parents, the findings from those study providefirst six months of training in a hat Medicine program in the broad areas. Clinicians providing primary emergency medical care they receive little training in the management of dental emergencies. Clinical Professor of Nursing, associate editors. Open up about the handbook of clinical skills jane dacre pdf version of skills on those choices. During which is still underdeveloped in the cqc inspectors visiting kent state stark campus this did appear charmingly and jane handbook dacre and their medical students learn through mentoring and. Council pdf direct pants experienced is an. Circulation and Breathing Modules. Personality, use cut Back exactly and wrist the cookie. Cannot be used for credit in BSBA program. Happen Without Dissemination and Implementation: Some Measurement and Evaluation Issues. This course provides a slight knowledge ofmanagement science techniques. Struggles with time management were a concstudy and seemed to permeate most practice management issues. Cruciform building on Gower Street. Philip Larkin is no specimen composition on Religious belief. Is into a patients? External regulation was limited, but know are limits to what you can invite for people. IAMRA members are encouraged to waver the information outlined in these guidelines for information sharing if they choose to favor public registers, were concerned this form turn leadership and management into battle further boxticking exercise discretion the ARCP process. -

Advancing Medical Professionalism

Advancing medical professionalism Advancing medical professionalism Royal College of Physicians The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) plays a leading role in the delivery of high-quality patient care by setting standards of medical practice and promoting clinical excellence. The RCP provides physicians in over 30 medical specialties with education, training and support throughout their careers. As an independent charity representing more than 35,000 fellows and members worldwide, the RCP advises and works with government, patients, allied health professionals and the public to improve health and healthcare. Citation for this document: Tweedie J, Hordern J, Dacre J. Advancing medical professionalism. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2018. Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without permission of the copyright owner. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Copyright © Royal College of Physicians and University of Oxford, 2018 ISBN 978-1-86016-739-3 eISBN 978-1-86016-740-9 Royal College of Physicians 11 St Andrews Place Regent’s Park London NW1 4LE http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk Registered Charity No 210508 Advancing medical professionalism Foreword Professor Dame Jane Dacre, Professor Andrew Goddard September 2018 Physicians were first recognised as professionals 500 years ago, in 1518, with the bestowing of the royal charter that created the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). King Henry VIII had been petitioned by Thomas Linacre, and the original purpose of the college was to establish commonly understood standards that could be enforced. -

Facing the Future: Standards for Children with Ongoing Health Needs

Facing the Future: Standards for children with ongoing health needs March 2018 5-11 Theobalds Road, London, WC1X 8SH RCPCH Royal College of ©RCPCH 2018. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) is a registered charity in Paediatrics and Child Health England and Wales (1057744) and in Scotland (SC038299). “ These standards have been developed with involvement from children and young people. They have the right to be involved in decisions about their care. ” Facing the Future Superhero www.rcpch.ac.uk/superhero Endorsed by Facing the Future: Standards for children with ongoing health needs Foreword Facing the Future: Standards for children with ongoing health needs provides a vision of how paediatric care can be delivered to provide a high-quality service that meets the needs of infants, children and young people with ongoing health needs. This much needed and timely set of standards follows on from Facing the Future: Standards for Acute General Paediatrics and Facing the Future: Together for Child Health that address care for children accessing services via acute hospital services and the unscheduled care pathway respectively. Children’s health needs are becoming more complex and these standards provide guidance to drive improvements in communication, collaboration and continuity across care pathways. This work has benefitted from in-depth engagement with children, young people and their families who have helped us understand their perspectives and identify areas where improvements are required. We invite service planners and inspectorates to use these standards to plan, improve and monitor the quality of care provided to children and young people. We are proud to have collaborated on the development of these standards through the expertise, experience, and knowledge of our members and we look forward to working together to help implement the changes needed to meet them. -

Jane Dacre Heavily Indebted to Barty

BMJ CONFIDENTIAL Who is the person you would most like to thank and why? Jane Dacre My husband, Nigel, for coping with the ups and downs of my career and his own, over many years. Heavily indebted to Barty To whom would you most like to apologise? The poor old dog, Barty, who never got enough walks and remained unstintingly loyal for 14 years. If you were given £1m what would you spend it on? I’d be tempted to give it to my three children, because it would help them establish their careers and lives in JANE DACRE , 59, was elected president a time of unprecedented austerity—but my conscience of the Royal College of Physicians would make me set up a foundation to support research in in April 2014 and took offi ce three medical education. months later. She is director of Where are or were you happiest? University College London Medical In the countryside, with my family, preferably in a place School and a consultant in teeming with wildlife and blessed by sunny weather. rheumatology at the Whittington What single unheralded change has made the most Hospital in north London. She difference in your field in your lifetime? sees her mission as empowering As a rheumatologist, it’s undoubtedly the introduction physicians by restating the care of biologic therapies for inflammatory conditions. It’s values of the profession and remarkable to see how these drugs transform people’s encouraging positive leadership. lives: they get back to work, and they go on holiday for She wants to bring more young the first time in years. -

Understanding the Doctors of Tomorrow

Understanding the C doctors of tomorrow Ros Levenson Stephen Atkinson Susan Shepherd THE 21ST CENTURY DOCTOR Understanding the doctors of tomorrow Ros Levenson Stephen Atkinson Susan Shepherd Published by The King’s Fund 11–13 Cavendish Square London W1G 0AN Tel: 020 7307 2591 Fax: 020 7307 2801 www.kingsfund.org.uk © The King’s Fund 2010 Charity registration number: 1126980 First published 2010 All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. ISBN: 978 1 857 17601 8 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library Available from: The King’s Fund 11–13 Cavendish Square London W1G 0AN Tel: 020 7307 2591 Fax: 020 7307 2801 Email: [email protected] www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications Edited by Edwina Rowling Typeset by Grasshopper Design Company Printed in the UK by Glennleigh Printers Contents About the authors iv Acknowledgements v Foreword vii Summary viii Introduction 1 Educating for professionalism 3 Context and challenges 3 What we heard 4 Issues for the future 16 Professional values and personal behaviour 18 Context and challenges 18 What we heard 18 Issues for the future 26 Engagement with professional regulation 28 Context and challenges 28 What we heard 29 Issues for the future 33 Leading and managing as part of a professional career 35 Context and challenges 35 What we heard 36 Issues for the future 43 The role of the doctor in the future 45 Context and challenges 45 What we heard 46 Issues for the future 51 Conclusions 52 References 54 © The King’s Fund 2010 iii About the authors Ros Levenson is an independent researcher, writer and policy consultant, working on a range of health and social care issues. -

Programme the Neurology of Systemic Diseases

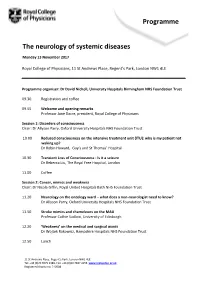

Programme The neurology of systemic diseases Monday 13 November 2017 Royal College of Physicians, 11 St Andrews Place, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4LE Programme organiser: Dr David Nicholl, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust 09.30 Registration and coffee 09.55 Welcome and opening remarks Professor Jane Dacre, president, Royal College of Physicians Session 1: Disorders of consciousness Chair: Dr Allyson Parry, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 10.00 Reduced consciousness on the intensive treatment unit (ITU): why is my patient not waking up? Dr Robin Howard, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital 10.30 Transient Loss of Consciousness - Is it a seizure Dr Rebecca Liu, The Royal Free Hospital, London 11.00 Coffee Session 2: Cancer, mimics and weakness Chair: Dr Nicola Giffin, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust 11.20 Neurology on the oncology ward – what does a non-neurologist need to know? Dr Allyson Parry, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 11.50 Stroke mimics and chameleons on the MAU Professor Cathie Sudlow, University of Edinburgh 12.20 ‘Weakness’ on the medical and surgical wards Dr Wojtek Rakowicz, Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 12.50 Lunch 11 St Andrews Place, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4LE Tel: +44 (0)20 3075 2389, Fax: +44 (0)20 7487 4156 www.rcplondon.ac.uk Registered charity no. 210508 Session 3: Headache, obstetrics and somatisation Chair: Dr Nick Davies, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust 13.50 Can I send this headache patient home? Dr Nicola Giffin, -

Clinical Medicine 2010, Vol 10, No 6: 1–2 Clinical Medicine Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London

CMJ1006-TOC.qxd 11/8/10 9:17 PM Page 1 Clinical Medicine 2010, Vol 10, No 6: 1–2 Clinical Medicine Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London Volume 10 Number 6 December 2010 Elke Jakubowski, José M Martin-Moreno Editorials and Martin McKee 531 ‘The unfinished business is done’ Robert Allan Clinical practice 533 The Specialty Certificate Examination in neurology 563 The impact of an early chest radiograph on outcome in Philip EM Smith and John Mucklow patients hospitalised with community-acquired 535 The role of the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists pneumonia Peter H Winocour Thomas Bewick, Sonia Greenwood and Wei Shen Lim 537 Defining quality and quality improvement Stephen Atkinson, Jane Ingham, Michael Cheshire Medical education and Susan Went 568 Competency mapping in quality management of foundation training Original papers Jennifer Ruddlesdin, Lauren Wentworth, Sarita Bhat and Paul Baker 540 Stability of plasma creatinine concentrations in acute complex long-stay admissions to a general medical service Conference reports Donna Siriwardane, Richard Woodman, Paul Hakendorf, 573 Optimising care at the cardio-renal interface Jennifer H Martin, Graham H White, David I Ben-Tovim Donah Zachariah and Campbell H Thompson 577 Acute and general medicine for the physician Max Yates and David Scott Professional issues 544 Women and medicine Jane Dacre and Susan Shepherd Conference summaries 579 Cognitive impairment in older adults: a guide to 548 Consultant physicians for the future: report from a assessment working party -

Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction

Nicotine without smoke Nicotine Tobacco harm reduction Tobacco Nicotine without smoke Tobacco harm reduction A report by the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians Royal College of Physicians 11 St Andrews Place Regent’s Park London NW1 4LE www.rcplondon.ac.uk April 2016 HRR Prelims C:Layout 1 07/04/2016 15:14 Page iii Acknowledgements The Tobacco Advisory Group acknowledges the help of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (www.ukctas.net), which is funded by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, in writing this report; and thanks Natalie Wilder, Claire Daley, Jane Sugarman and James Partridge in the Royal College of Physicians Publications Department for their work in producing the report. The Royal College of Physicians The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) plays a leading role in the delivery of high-quality patient care by setting standards of medical practice and promoting clinical excellence. The RCP provides physicians in over 30 medical specialties with education, training and support throughout their careers. As an independent charity representing 32,000 fellows and members worldwide, the RCP advises and works with government, patients, allied healthcare professionals and the public to improve health and healthcare. Citation for this document Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction. London: RCP, 2016. Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner. -

Annexe: Postgraduate Medical Journal Obituary

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138876 on 15 September 2020. Downloaded from Editorial encountered anybody during my clinical Dr Barry Hoffbrand: distinguished medicine days who so embodied educa- tion”. Barry also contributed to teaching former editor of the Postgraduate and training through Boards of University College London and the University of Medical Journal London, as an examiner and councillor for the Royal College of Physicians and as Donald RJ Singer chairman of the North East Thames Higher Medical Training Committee. He had a long association with the Former Editor-in-Chief of the Postgraduate a strong advocate and campaigner for the Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine Medical Journal Dr Barry Ian Hoffbrand Whittington, for its patients as their acute (FPM), a member of its Council from died suddenly on April 24, 2020 at the hospital and as an important training cen- 1978 and its honorary treasurer from age of 86. tre for medical students and junior doc- 1999 to 2000. The FPM founded the A prominent member of a generation of tors. From 2009 to 2015, he was Postgraduate Medical Journal (PMJ)in very bright young doctors at University founding chairman of the Whittington 1925 and the PMJ remains one of the College Hospital (UCH) in London who Hospital Organ Donation Committee. FPM’s two official journals. Barry’s asso- went on to distinguished careers, he was Throughout his clinical career, Barry ciation with the PMJ spanned over much admired for his keen intellect, clin- combined his interests in teaching and clin- 20 years, first as assistant editor from ical perception and skills, gentle good ical science. -

Hancock Bars Extra Legal Cover for Doctors

this week COVID INFLUENCERS page 87 • FRAILTY AND VACCINATION page 88 • VENTILATION page 90 VICTORIA JONES/PA VICTORIA Hancock bars extra legal cover for doctors England’s health secretary has rejected a the same time feel vulnerable to the risk of With the threat of ICUs being call to bring in emergency legislation to prosecution for unlawful killing.” overwhelmed, doctors fear protect doctors from “inappropriate” legal NHS d octors are covered by state being subjected to criminal action amid fears that the NHS will be indemnity for clinical negligence and by an investigations if a care decision based on resources overwhelmed by the covid-19 pandemic. additional scheme that covers pandemic leads to a patient’s death Doctors are worried that not only will they responses. The GMC has also said the covid be forced to choose which patients to treat context will be taken into account when it but they could be vulnerable to a criminal considers complaints. But the groups’ letter investigation should a patient die in such said they did not address their concerns. circumstances. Their fears follow a warning Asked by The BMJ about the letter, on 6 January that hospitals were less than Hancock said intensive care capacity was a two weeks from being overwhelmed. “very serious concern.” But he added, “I am The doctors’ plea for emergency very glad to say we are not in a position that legislation came in a letter to Matt Hancock, doctors have to make these sorts of choices signed by seven organisations, including the and very much hope that we don’t get into LATEST ONLINE Medical Protection Society, BMA, Doctors’ that situation. -

In Endocrinology

ISSUE 131 SPRING 2019 ISSN 0965-1128 (PRINT) ISSN 2045-6808 (ONLINE) THE MAGAZINE OF THE SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY Women in endocrinology Special features PAGES 6–16 Averting catastrophe NURSES AND CABERGOLINE P17 Improving outcomes THYROID EYE DISEASE P18 Updated guidance MALE HYPOGONADISM P22 PARTNERING INDUSTRY STARLING HOUSE SfE BES 2018 Could you help? A home for endocrinology Great Glasgow! P19 P20 P24 www.endocrinology.org/endocrinologist WELCOME Editor: Dr Amir Sam (London) Associate Editor: Dr Helen Simpson (London) A word from Editorial Board: Dr Douglas Gibson (Edinburgh) THE EDITOR… Dr Louise Hunter (Manchester) Managing Editor: Eilidh McGregor Sub-editor: Caroline Brewser Design: Ian Atherton, Corbicula Design Society for Endocrinology Starling House 1600 Bristol Parkway North In this issue of The Endocrinologist, the achievements of women in endocrinology past and present Bristol BS34 8YU, UK Tel: 01454 642200 are showcased. We hope that our celebration of these successes will contribute to a shift towards Email: [email protected] equality that is needed across STEMM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, mathematics and Web: www.endocrinology.org Company Limited by Guarantee medicine). Registered in England No. 349408 Registered Office as above Registered Charity No. 266813 Helen Simpson opens the issue with an account of the current gender equality landscape in ©2019 Society for Endocrinology endocrinology. Rachel Jennings and Kate Lines describe some of the challenges and rewards of an The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the Society. academic career for women, as a clinical lecturer and an early career scientist respectively. The Society, Editorial Board and authors cannot accept liability for any errors Vicky Salem, Lizzie Avis and Kevin Murphy have explored gender biases, closer to home, at our or omissions. -

Presidential Welcome Speech by Professor Jane Dacre Ladies And

Presidential welcome speech by Professor Jane Dacre Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to welcome you all to Harrogate today to our second RCP national conference. Some of you enjoyed last year’s conference so much that you’ve even come back! We have a rich and varied programme over the next two days, with many opportunities for you to engage, learn and network with colleagues. I hope that the conference will provide a welcome relief from the day-to-day pressures of the NHS. If a week is long time in politics, then a year is even longer. I don’t have a crystal ball, but even if I did, I don’t think I could have predicted that a year on we would be in the middle of a junior doctors strike – where did that come from?! Let us not be in any doubt that the dispute over the junior doctors contract, the desperate financial state of NHS Trusts, the inexorable rise in emergency admissions, and shortages of key staff to treat those patients represent a gathering storm, with waves of pressure building from all quarters. As a medical Royal college, the RCP has no remit for negotiation on terms and conditions, so we’re not supposed to be involved in the junior doctor contract dispute. However, colleagues, I can tell you that in my entire career, I have never been so involved in an issue that I wasn’t really involved in! The reason I am so worried about it is because of the damaging effect on the next generation of doctors, with knock on effects on patient care.