The European CRT Survey: 1 Year (9–15 Months) Follow-Up Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Besluit Interne Relatieve Bevoegdheid Rechtbank Overijssel Vastgesteld 11 Maart 2014

Besluit interne relatieve bevoegdheid rechtbank Overijssel Vastgesteld 11 maart 2014 Nadere regels als bedoeld in artikel 6 van het zaaksverdelingsreglement 1. Indien in het schema onder punt 2 van het zaaksverdelingsreglement in de kolom “loket” één locatie is vermeld, dienen (de stukken inzake) deze zaken op de desbetreffende locatie te worden ingediend. 2. Indien in het schema onder punt 2 van het zaaksverdelingsreglement in de kolom “loket” meerdere locaties zijn vermeld bij een categorie zaken, zijn voor de beantwoording van de vraag bij welke locatie (de stukken inzake) deze zaken moeten worden ingediend, de wettelijke bevoegdheidsregels van overeenkomstige toepassing. 3. Voor het dagvaarden in een zaak over huur, arbeid, pacht, consumentenaangelegenheden, alsmede voor het indienen van civiele vorderingen tot € 25.000 en verzoeken tot het instellen van bewind, mentorschap, voogdij of curatele, bevatten de in bijlage 1 genoemde locaties de daarbij genoemde gemeenten. 4. Voor het indienen van alle andere zaken bevatten de in bijlage 2 genoemde locaties de daarbij genoemde gemeenten. 5. Kan aan de hand van het vorenstaande niet worden vastgesteld waar een zaak moet worden ingediend, dan moet de zaak worden ingediend bij de locatie Zwolle. 6. De rechter-commissaris in strafzaken van de locatie waar een zaak volgens dit besluit moet worden ingediend, kan zijn werkzaamheden overdragen aan een rechter-commissaris op een andere locatie. Vastgesteld door het gerechtsbestuur te Zwolle op 11 maart 2014 datum 11 maart 2014 pagina 2 van 3 BIJLAGE -

Viral and Bacterial Infection Elicit Distinct Changes in Plasma Lipids in Febrile Children

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/655704; this version posted May 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Viral and bacterial infection elicit distinct changes in plasma lipids in febrile children 2 Xinzhu Wang1, Ruud Nijman2, Stephane Camuzeaux3, Caroline Sands3, Heather 3 Jackson2, Myrsini Kaforou2, Marieke Emonts4,5,6, Jethro Herberg2, Ian Maconochie7, 4 Enitan D Carrol8,9,10, Stephane C Paulus 9,10, Werner Zenz11, Michiel Van der Flier12,13, 5 Ronald de Groot13, Federico Martinon-Torres14, Luregn J Schlapbach15, Andrew J 6 Pollard16, Colin Fink17, Taco T Kuijpers18, Suzanne Anderson19, Matthew Lewis3, Michael 7 Levin2, Myra McClure1 on behalf of EUCLIDS consortium* 8 1. Jefferiss Research Trust Laboratories, Department of Medicine, Imperial College 9 London 10 2. Section of Paediatrics, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London 11 3. National Phenome Centre and Imperial Clinical Phenotyping Centre, Department of 12 Surgery and Cancer, IRDB Building, Du Cane Road, Imperial College London, 13 London, W12 0NN, United Kingdom 14 4. Great North Children’s Hospital, Paediatric Immunology, Infectious Diseases & 15 Allergy, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon 16 Tyne, United Kingdom. 17 5. Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 18 Kingdom 19 6. NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre based at Newcastle upon Tyne 20 Hospitals NHS Trust and Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 21 Kingdom 22 7. Department of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College 23 NHS Healthcare Trust, London, United Kingdom 24 8. -

Route Arnhem

Route Arnhem Our office is located in the Rhine Tower From Apeldoorn/Zwolle via the A50 (Rijntoren), commonly referred to as the • Follow the A50 in the direction of Nieuwe Stationsstraat 10 blue tower, which, together with the Arnhem. 6811 KS Arnhem (green) Park Tower, forms part of Arnhem • Leave the A50 via at exit 20 (Arnhem T +31 26 368 75 20 Central Station. Center). • Follow the signs ‘Arnhem-Center’ By car and the route via the Apeldoornseweg as described above. Parking in P-Central Address parking garage: From Nijmegen via the A325 Willemstunnel 1, 6811 KZ Arnhem. • Follow the A325 past Gelredome stadium From the parking garage, take the elevator in the direction of Arnhem Center. ‘Kantoren’ (Offices). Then follow the signs • Cross the John Frost Bridge and follow ‘WTC’ to the blue tower. Our office is on the the signs ‘Centrumring +P Station’, When you use a navigation 11th floor. which is the road straight on. system, navigate on • After about 2 km enter the tunnel. ‘Willemstunnel 1’, which will From The Hague/ Utrecht (=Den Bosch/ The entrance of parking garage P-Central lead you to the entrance of Eindhoven) via the A12 is in the tunnel, on your right Parking Garage Central. • Follow the A12 in the direction of Arnhem. By public transport • Leave the A12 at exit 26 (Arnhem North). Trains and busses stop right in front of Via the Apeldoornseweg you enter the building. From the train or bus Arnhem. platform, go to the station hall first. From • In the built-up area, you go straight down there, take the escalator up and then turn the road, direction Center, past the right, towards exit Nieuwe Stationsstraat. -

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Woonakkoord Oost Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Met trots bieden we u het Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland aan en nodigen het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties uit samen hieraan verder te bouwen. Een akkoord dat de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen, de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede en de provincies Overijssel en Gelderland met het Rijk willen sluiten. We zijn blij dat het Rijk de grote urgentie van de woningbouwopgave in Oost-Nederland ziet en daar met ons op verder wil bouwen. We willen in genoemde steden en regio’s in de komende 5 jaar 75.000 woningen bijbouwen voor starters, doorstromers en alleenstaanden. We zijn bereid om naar innovatieve en flexibele bouwwijzen en verstedelijking te kijken om snel en slim mensen van een huis te voorzien. De Randstad verschuift naar het Oosten Alleen al vanuit de Randstad verwachten we de komende 5 jaar zo’n 60.000 nieuwe huishoudens in het oosten. De verhuisstroom uit de Randstad zorgt voor een snelle verstedelijking in onze steden. Er is nog steeds een grote verhuisstroom naar de Randstad, maar dat zijn vooral jonge mensen die geen huis achter laten. De nieuwkomers vanuit de Randstad zijn vooral gezinnen en ouderen die een nieuwe woning zoeken. We delen de grote woonopgave op in een woondeal voor de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen waar de woningnood het meest urgent is en een verstedelijkingsstrategie voor de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede. Met aandacht voor de bereikbaarheid van de steden en binnen de steden. Het gaat daarbij niet alleen om weg-, spoor- en fietsverbindingen, maar ook om nieuwe vormen van mobiliteit. -

The Path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR for More Than 600 Years, a Unique Network HANSA of Merchants Existed in Northern Europe

The path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR For more than 600 years, a unique network HANSA of merchants existed in Northern Europe. The cooperation of this consortium of merchants for the promotion of their foreign trade gave rise to an association of cities, to which around 200 coastal and inland cities belonged in the course of time. The Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages These cities were located in an area that today encom- passes seven European countries: from the Dutch Zui- derzee in the west to Baltic Estonia in the east, and from Sweden‘s Visby / Gotland in the north to the Cologne- Erfurt-Wroclaw-Krakow perimeter in the south. From this base, the Hanseatic traders developed a strong economic in uence, which during the 16th century extended from Portugal to Russia and from Scandinavia to Italy, an area that now includes 20 European states. Honest merchants – Fair Trade? Merchants, who often shared family ties to each other, were not always fair to producers and craftsmen. There is ample evidence of routine fraud and young traders in far- ung posts who led dissolute lives. It has also been proven that slave labor was used. ̇ ̆ Trading was conducted with goods that were typically regional, and sometimes with luxury goods: for example, wax and furs from Novgorod, cloth, silver, metal goods, salt, herrings and Chronology: grain from Hanseatic cities such as Lübeck, Münster or Dortmund 12th–14th Century - “Kaufmannshanse”. Establishment of Hanseatic trading posts (Hanseatic kontors) with common privi- leges for Low German merchants 14th–17th Century - “Städtehanse”. Cooperation between the Hanseatic cit- ies to defend their trade privileges and Merchants from di erent cities in di erent enforce common interests, especially at countries formed convoys and partnerships. -

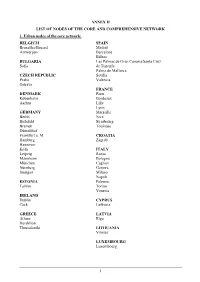

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

Why Did the Netherlands Develop So Early? the Legacy of the Brethren of the Common Life

CPB Discussion Paper | 228 Why Did the Netherlands Develop so Early? The Legacy of the Brethren of the Common Life İ. Semih Akçomak Dinand Webbink Bas ter Weel Why Did the Netherlands Develop so Early? The Legacy of the Brethren of the Common Life* İ. Semih Akçomak Middle East Technical University [email protected] Dinand Webbink Erasmus University Rotterdam and CPB [email protected] Bas ter Weel CPB and Maastricht University [email protected] Abstract This research provides an explanation for high literacy, economic growth and societal developments in the Netherlands in the period before the Dutch Republic. We establish a link between the Brethren of the Common Life (BCL), a religious community founded by Geert Groote in the city of Deventer in the late fourteenth century, and the early development of the Netherlands. The BCL stimulated human capital accumulation by educating Dutch citizens without inducing animosity from the dominant Roman Catholic Church or other political rulers. Human capital had an impact on the structure of economic development in the period immediately after 1400. The educated workforce put pressure on the Habsburg monarchy leading to economic and religious resentment and eventually to the Revolt in 1572. The analyses show that the BCL contributed to the high rates of literacy in the Netherlands. In addition, there are positive effects of the BCL on book production and on city growth in the fifteenth and sixteenth century. Finally, we find that cities with BCL-roots were more likely to join the Dutch Revolt. These findings are supported by regressions that use distance to Deventer as an instrument for the presence of BCL. -

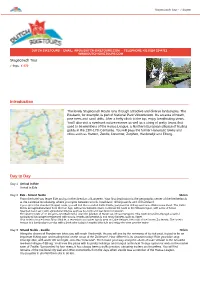

Introduction Day To

Stagecoach Tour - 7 dagen DUTCH BIKETOURS - EMAIL: [email protected] - TELEPHONE +31 (0)24 3244712 - WWW.DUTCH-BIKETOURS.COM Stagecoach Tour 7 days, € 570 Introduction The lovely Stagecoach Route runs through attractive and diverse landscapes. The Posbank, for example, is part of National Park Veluwezoom. It’s an area of heath, pine trees and sand drifts. After a hefty climb to the top, enjoy breathtaking views. You’ll also visit a riverbank nature reserve as well as a string of pretty towns that used to be members of the Hansa League, a Northern European alliance of trading guilds in the 13th-17th Centuries. You will pass the former Hanseatic towns and cities such as Hattem, Zwolle, Deventer, Zutphen, Harderwijk and Elburg. Day to Day Day 1 Arrival in Ede Arrival in Ede Day 2 Ede - Strand Nulde 56 km From the hotel you leave Ede and go in the direction of Lunteren. Your first destination is the geographic center of the Netherlands at the Lunterse Goudsberg, where you cycle between woods, heathland, drifting sands and old farmland. If you opt for the standard (longer) route, you will find the so-called Celtic Fields, just past the drifting sand area Wek eromse Zand. The Celtic Fields are agricultural land from the Iron Age, with a reconstructed farm. Continue the route to the Veluwe region, with a mix of forest, heathland and sand with agricultural villages such as Kootwijk and Garderen in between. The shorter route of 47 km goes over Barneveld, once the junction of Hanze and Hessen weggen. This route meanders through a varied agricultural landscape interspersed with woods, heaths and peatlands and many hamlets such as Appel. -

Pharmacodynamics, Pharmacokinetics, and Safety Of

European Heart Journal (2019) 0, 1–9 CLINICAL RESEARCH doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz807 Thrombosis and antithrombotic therapy Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz807/5625727 by University of Newcastle user on 14 January 2020 Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of single-dose subcutaneous administration of selatogrel, a novel P2Y12 receptor antagonist, in patients with chronic coronary syndromes Robert F. Storey 1*, Paul A. Gurbel2, Jurrien ten Berg 3, Corine Bernaud 4, George D. Dangas5, Jean-Marie Frenoux 4, Diana A. Gorog 6,7, Abdel Hmissi 4, Vijay Kunadian8,9, Stefan K. James 10, Jean-Francois Tanguay11, Henry Tran2, Dietmar Trenk 12, Mike Ufer4, Pim Van der Harst 13, Arnoud W.J. Van’t Hof 14,15,16, and Dominick J. Angiolillo17 1Department of Infection, Immunity and Cardiovascular Disease, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK; 2Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, VA, USA; 3Department of Cardiologie, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, Netherlands; 4Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland; 5Division of Cardiology, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, USA; 6University of Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire, UK; 7National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, UK; 8Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK; 9Cardiothoracic Centre, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundations Trust, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK; 10Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala University, Uppsala, -

An Outline History of the Hanseatic League, More Particularly in Its

An Outline History of the Hanseatic League, More Particularly in Its Bearings upon English Commerce Author(s): Cornelius Walford Reviewed work(s): Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 9 (1881), pp. 82-136 Published by: Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3677937 . Accessed: 03/03/2012 00:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. http://www.jstor.org AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE HANSEATIC LEAGUE, MORE PARTICULARLY IN ITS BEARINGS UPON ENGLISH COMMERCE. BY CORNELIUSWALFORD, F.I.A., FS.S.S, F.R.HIST.SOC. [Read beforeRoyal Hist l Society, 19th Feb., I88o.] IN calling the attention of the fellows to some of the leading points in the history of one of the most remarkable confedera- tions which the world has ever seen, and in endeavouring to arrange these into an harmonious and intelligent narrative, I feel that I owe no apology, except at least to the extent to which my labours may be found deficient or defective: for it is in the direction of such original inquiries as the present that our Society may perform its more useful offices. -

Workbook I - Project Analysis

Beyond Plan B - Workbook I - Project Analysis http://www.timetoast.com/timelines/hanseatic-league Alliance with Hamburg Dutch-Hanseatic war European Economic Merger New trade routes Hanseatic League War with Denmark Breaking of Hansa's monopoly on the Baltic Community Treaty 1241 Hansa 15% of Danish trade profits Begining of the Hansa's decline 1958 1967 1159 1227 1266 1282 1356 1361 1370 1438 1441 1593 1669 1862 Establishment Lübeck became Charter operations Cologne joined Expansion Decline Last meeting End of the Hansa Rebuilding of Lübeck free imperial city in England New trading product Hansa trading posts began to close Only 9 members attended Began to form guilds or Hansa Own rules Monopolisation the Baltic No taxes Flo Beck via Wikipedia.org Effects The League organized and controled trade throughout Hanseatic trade route. Main trading route of the northern Europe by winning commercial privileges and monopolies and by establishing trading bases overseas. Hanseatic League in the Northern Europe. Coast of nothern Europe all the member towns. 1358-1862 Cologne (Rhine River) ≈500 years Hamburg and Bremen (North Sea) Scale core semi peri LOCAL Investment REGIONAL marinemaler-olaf-rahardt.com via Wikipedia.org Hanseatic flagship of Lübeck to uphold its EU ? long-privileged commercial position. WORLD The Hanseatic League was a business alliance of trading cities and their guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe and flourished from the 1200 to 1500. The chief cities were Cologne on the Rhine River, Hamburg and Bremen on the North Sea, and Lübeck on the Baltic. Each Deutsche Fotothek via Wikipedia.org city had its own legal system and a degree of political autonomy. -

ABS004: the Concept, Prevalence and Consequences of Low the Benefits of ICS Are Less Clear

186 Abstracts ABS004: The concept, prevalence and consequences of low the benefits of ICS are less clear. Aim: To evaluate the tolerance to ICS in asthma effectiveness of fluticasone propionate (FP) in preschool a b b c children with recurrent respiratory symptoms in general Rob Horne , David Price , Amanda Lee , Stan Musgrave practice. Subjects and methods: 96 children aged 1—5 year a University of Brighton, Mayfield House, Falmer Campus, (mean age 2.6; 69%male) consulting their general practitioner (GP) for respiratory symptoms and in whom treatment with ICS Brighton, BN1 9PH, United Kingdom b Aberdeen, United was considered by the GP participated in a multi-center, double- Kingdom c East Anglia, United Kingdom blind, placebo controlled study (ASTERISK). Participants were randomly assigned to either FP 100 mcg or placebo twice daily Introduction: The concept of low tolerance to ICS can be via MDI + spacer for 6 months. Daily record cards completed by extended beyond the experience of side effects to include the parents were used to evaluate symptoms (cough, wheeze, conceptual barriers such as doubts about personal need for ICS, and shortness of breath) at 1, 3, and 6 months. In addition, lung and concerns about ICS. Aims and objectives: To assess the function was measured by means of the interrupter technique prevalence of low tolerance to ICS and consequences in terms and the forced oscillation technique. Results: Both groups of ICS adherence and asthma control. Subjects and methods: showed a significant improvement in total symptom score during 2372 patients managed in primary care at steps 2 and 3 of the study period, with no difference between both treatment the asthma guidelines who participated in the Asthma Control, groups.