CURRENT EVENTS Lesson of the Day: 'The Lost Diaries of War'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Apostillen Der Stad Campen En Haar Jurisdictie, 1796-1803

De Apostillen der Stad Campen en haar Jurisdictie Bewerking van inv. nr. 210 van het Oud Archief (Apostillen 1796-1803) Door Jan van Hulzen Kamper genealogische en historische bronnen deel 26 T Uitgegeven met medewerking van het Archief van de gemeente Kampen 2009 Ontwerp omslag: Marcel van Hulzen Omslagillustratie: Detail Stadswapen van Kampen Omslag Burgerboek anno 1667 Inventaris nr. Oud Archief (O.A.) 334 Gemeente Archief Kampen Apostillen van Campen en haar Jurisdictie. 1624-1809. Deel 26 T. 2 jan. 1796 – 12dec. 1803. Inv. nr. O.A. 210. De Apostillen van de stad Kampen zijn een verzameling folianten bestaande uit 21 delen die zich bevinden in het Gemeente Archief onder Oud Archief [O.A.] inventaris nr‟s 191 t/m 211 en behelzen een periode vanaf 1624 t/m 1809. Het werk bestaat uit een groot aantal rekesten –verzoek of bezwaarschriften– die door de inwoners van de stad, alsmede de bewoners van het buitengebied,- wat onder de jurisdictie van de stad viel - werden gericht aan de Schepenen en Raad van Campen over iets hinderlijks, onbillijks of om derglijke gunsten te verwerven. Ook voor personen wonende buiten de jurisdictie van Kampen, die in de stad belangen hadden verworven, was het mogelijk een rekest in te dienen. De rekesten werden door Schepenen en Raad voorzien van een apostille, een kanttekening met toelichting als antwoord op het verzoek, wat meestal gunstig uitviel. Door het bestuderen van de Apostillen krijgt men een aardige indicatie wat de mensen in deze periode van onze geschiedenis zoal bezig hield, en geeft als het ware het leven van alle dag weer. -

Who Was Anne Frank? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHO WAS ANNE FRANK? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ann Abramson,Nancy Harrison | 103 pages | 01 Feb 2007 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448444826 | English | New York, United States Who Was Anne Frank? PDF Book Upon his death, Otto willed the diary's copyright to the Fonds, on the provision that the first 80, Swiss francs in income each year was to be distributed to his heirs. Her writings reveal a teenage girl with creativity, wisdom, depth of emotion and rhetorical power far beyond her years. She is seen leaning out of a second-floor window in an attempt to better view the bride and groom. In , Otto Frank took action against Heinz Roth of Frankfurt, who published pamphlets stating that the diary was "a forgery". Her life and writings have inspired a diverse group of artists and social commentators to make reference to her in literature, popular music, television, and other media. Archived from the original on 14 April When a man named Edgar Geiss distributed the same pamphlet in the courtroom, he too was prosecuted. It was first published in Germany and France in , and after being rejected by several publishers, was first published in the United Kingdom in Frank decided she would use it as a diary, [22] and she began writing in it almost immediately. Anne Frank is included as one of the topics in the Canon of Dutch History , which was prepared by a committee headed by Frits van Oostrom and presented to the Minister of Education, Culture and Science, Maria van der Hoeven , in ; the Canon is a list of fifty topics that aims to provide a chronological summary of Dutch history to be taught in primary schools and the first two years of secondary school in the Netherlands. -

The Volcanic Foundation of Dutch Architecture: Use of Rhenish Tuff and Trass in the Netherlands in the Past Two Millennia

The volcanic foundation of Dutch architecture: Use of Rhenish tuff and trass in the Netherlands in the past two millennia Timo G. Nijland 1, Rob P.J. van Hees 1,2 1 TNO, PO Box 49, 2600 AA Delft, the Netherlands 2 Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands Occasionally, a profound but distant connection between volcano and culture exists. This is the case between the volcanic Eifel region in Germany and historic construction in the Netherlands, with the river Rhine as physical and enabling connection. Volcanic tuff from the Eifel comprises a significant amount of the building mass in Dutch built heritage. Tuffs from the Laacher See volcano have been imported and used during Roman occupation (hence called Römer tuff). It was the dominant dimension stone when construction in stone revived from the 10th century onwards, becoming the visual mark of Romanesque architecture in the Netherlands. Römer tuff gradually disappeared from the market from the 12th century onwards. Early 15th century, Weiberner tuff from the Riedener caldera, was introduced for fine sculptures and cladding; it disappears from use in about a century. Late 19th century, this tuff is reintroduced, both for restoration and for new buildings. In this period, Ettringer tuff, also from the Riedener caldera, is introduced for the first time. Ground Römer tuff (Rhenish trass) was used as a pozzolanic addition to lime mortars, enabling the hydraulic engineering works in masonry that facilitated life and economics in the Dutch delta for centuries. Key words: Tuff, trass, Eifel, the Netherlands, natural stone 1 Introduction Volcanic tuffs have been used as building stone in many countries over the world. -

Water Opportunities

One Valley Two Rivers Three container terminals Water opportunities Logistics Valley, the Gelderland Transport Corridor, between the large sea ports and the European hinterland from Duisburg to Genoa, isn’t all about roads and trains. The river Rhine and the river IJssel, a tributary, comprise the ultimate no-traffic-jam way of transportation. Transport by barge keeps road traffic more fluent, which is a plus for the environment and offers extra benefits for the shipper. Intermodality Moving, storing and servicing containers and which is close by. Each of the three frequent barge connections with important cooperating Gelderland container terminals hubs on waterways like Duisburg, Antwerp, has an E-road next door. Near Valburg, Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Add intermodal bordering on Nijmegen, a new train terminal transport to this 24-7 service by rail and road is in the making. All three terminals in because of the proximity of highways and Doesburg, Nijmegen and Tiel use train connections by rail and the mix these after-shipping as standard. terminals are offering becomes tempting. The new Silk Route by train from China, The big plus: no traffic jams. Your by way of Kazakhstan, ends in Duisburg, transportation is on schedule and robust. Terminal Doesburg Terminal Nijmegen Terminal Tiel A tight weave The Netherlands boasts a tight weave of 4,800 kilometres of waterways, suited for transporting goods. The most important cities are connected by canals and lakes. Doesburg Regional distribution from the quays is standard practice. 4,800 km of waterways Tiel Nijmegen Cooperation The terminals sport deep water, even at ‘We offer you a stable barge network in Gelderland. -

Tiel - Medel Park

TIEL - MEDEL PARK State of the art logistics distribution centre at Prinsenhof 11 in Tiel Total GLA 22,373m2 | Immediately available 3hr Location CTU Rivierenland This property is located at the Medel business park in Tiel, N835 De Prinsenhof 11 in the centre of the Netherlands, making it a primary place of business for many logistics companies. Medel 2hr 34 • Medel business park has developed over the recent 34 AMSTERDAM years into one of the logistics hot spots in the UTRECHT N835 THE HAGUE Zoelen Echteld TIEL A15 Netherlands, attracting major logistics operators and MÜNSTER N323 1hr retailers like H&M, Lidl, Kuehne + Nagel, DHL and Van ROTTERDAM Gend & Loos E31 MOERDIJK A15 • Direct access from the A15 motorway Ooij EINDHOVEN DORTMUND • Surrounding road network provides easy access to ESSEN ANTWERP Drumpt Den Akker Rotterdam, Schiphol airport, Antwerpen and the Ruhr GHENT DUSSELDORF • Directly connected to the inland waterways by means BRUSSELS of the local barge terminal (CTU Rivierenland) at the Amsterdam-Rijn canal. Easy access to Barge Excellent terminal connections Design Specifications CTU Rivierenland Warehouse Overview N835 DCAM TIEL This modern standalone logistics site comprises a total De Prinsenhof 11 leasable area of approximately 22,373m2 divided over • Clear stacking height of approx. 10.80 meters Medel 18,989m² warehouse space, 700m² office space and a • Column structure of 11.5 x 22.8 meters 34 mezzanine of 2,684m². 34 • Concrete wall base of 1 meter N835 The building also features a concrete wall base of at Zoelen Echteld A15 • 21 loading docks with electrically operated overhead N323 least 1 meter above the warehouse floor, is completely fenced and has 140 dedicated car parking spaces in doors of 3 x 3 meters and electrical hydraulic levelers with a load-bearing capacity of 60 kN/m2 E31 front of the office. -

Indeling Van Nederland in 40 COROP-Gebieden Gemeentelijke Indeling Van Nederland Op 1 Januari 2019

Indeling van Nederland in 40 COROP-gebieden Gemeentelijke indeling van Nederland op 1 januari 2019 Legenda COROP-grens Het Hogeland Schiermonnikoog Gemeentegrens Ameland Woonkern Terschelling Het Hogeland 02 Noardeast-Fryslân Loppersum Appingedam Delfzijl Dantumadiel 03 Achtkarspelen Vlieland Waadhoeke 04 Westerkwartier GRONINGEN Midden-Groningen Oldambt Tytsjerksteradiel Harlingen LEEUWARDEN Smallingerland Veendam Westerwolde Noordenveld Tynaarlo Pekela Texel Opsterland Súdwest-Fryslân 01 06 Assen Aa en Hunze Stadskanaal Ooststellingwerf 05 07 Heerenveen Den Helder Borger-Odoorn De Fryske Marren Weststellingwerf Midden-Drenthe Hollands Westerveld Kroon Schagen 08 18 Steenwijkerland EMMEN 09 Coevorden Hoogeveen Medemblik Enkhuizen Opmeer Noordoostpolder Langedijk Stede Broec Meppel Heerhugowaard Bergen Drechterland Urk De Wolden Hoorn Koggenland 19 Staphorst Heiloo ALKMAAR Zwartewaterland Hardenberg Castricum Beemster Kampen 10 Edam- Volendam Uitgeest 40 ZWOLLE Ommen Heemskerk Dalfsen Wormerland Purmerend Dronten Beverwijk Lelystad 22 Hattem ZAANSTAD Twenterand 20 Oostzaan Waterland Oldebroek Velsen Landsmeer Tubbergen Bloemendaal Elburg Heerde Dinkelland Raalte 21 HAARLEM AMSTERDAM Zandvoort ALMERE Hellendoorn Almelo Heemstede Zeewolde Wierden 23 Diemen Harderwijk Nunspeet Olst- Wijhe 11 Losser Epe Borne HAARLEMMERMEER Gooise Oldenzaal Weesp Hillegom Meren Rijssen-Holten Ouder- Amstel Huizen Ermelo Amstelveen Blaricum Noordwijk Deventer 12 Hengelo Lisse Aalsmeer 24 Eemnes Laren Putten 25 Uithoorn Wijdemeren Bunschoten Hof van Voorst Teylingen -

Newcastle University E-Prints

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 21st March 2013 Version of file: Published Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: McGrady MG, Ellwood RP, Maguire A, Goodwin M, Boothman N, Pretty IA. The association between social deprivation and the prevalence and severity of dental caries and fluorosis in populations with and without water fluoridation. BMC Public Health 2012,12(1), 1122. Further information on publisher website: http://www.biomedcentral.com Publisher’s copyright statement: © 2012 McGrady et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The definitive version of this article is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1122 Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. -

Pioneer.V12i1.485

DOI: https://doi.org/10.36841/pioneer.v12i1.485 PIONEER VOLUME 12, Issue 1, June 2020: 55 - 72 FRAN.‘S CRITICIS0 TOWARD NAZIS0 AS SEEN F520 THE LIVES OF THE CHARACTERS IN THE DIARY OF A YOUNG GIRL Adriya Vitalya Gemilang Universitas Sarjanawiyata Tamansiswa Yogyakarta [email protected] Abstract: This research is analyzing a diary by Anne Frank. It tells the readers about the lives of the Jews during the Nazi occupation. The diary describes the experiences of the Jews in order to survive during Nazism. It tells how the Jews are discriminated and suffered by Nazism. Anne Frank describes their everyday life vividly and in honest way which brings the readers to understand their experiences without experience it. The objective of this research is to identify Frank‘s criticism toward 1azism as seen from the lives of the characters. In order to accomplish the objectives, the library research is used since many data and theories are collected from some books. In order to analyze the problem, the writer employs the sociocultural-historical approach. It is used to identify criticism toward Nazism. The result of the analysis shows that there is Frank‘s criticism toward 1azism in the description of the lives of the characters under the 1azis occupation. Through her diary, Anne Frank criticizes the discrimination, the lack of education, the hunger, the chaos and the mass killing during the reign of Nazism in the Netherlands. Keywords: Frank‘s criticism, nazism, the diary of a young girl INTRODUCTION History has a function to awaken human about the process of revolution and society development in time dimension, which is to build perspective and historical consciousness in discovering the past, the present, and the future. -

Loe De Jong 1914-2005

boudewijn smits Loe de Jong 1914-2005 Historicus met een missie bijlagen 8 tot en met 11 Boom Amsterdam inhoud bijlage 8 NOTEN Inleiding 5 Hoofdstuk 1 7 Hoofdstuk 2 19 Hoofdstuk 3 35 Hoofdstuk 4 53 Hoofdstuk 5 70 Hoofdstuk 6 82 Hoofdstuk 7 100 Hoofdstuk 8 111 Hoofdstuk 9 119 Hoofdstuk 10 131 Hoofdstuk 11 141 Hoofdstuk 12 154 Hoofdstuk 13 166 Hoofdstuk 14 178 Hoofdstuk 15 190 Hoofdstuk 16 200 Hoofdstuk 17 215 Hoofdstuk 18 223 Hoofdstuk 19 234 Hoofdstuk 20 243 Hoofdstuk 21 256 Hoofdstuk 22 266 Hoofdstuk 23 272 Hoofdstuk 24 288 Hoofdstuk 25 301 Hoofdstuk 26 315 Hoofdstuk 27 327 Hoofstuk 28 339 Hoofstuk 29 350 Hoofdstuk 30 360 Slotbeschouwing 371 bijlage 9 english summery 373 bijlage 10 geÏnterVIEWDE Personen 383 bijlage 11 geraadPleegde arChieVen 391 bijlage 8 NOTEN inleiding 1 Ernst H. Kossmann, ‘Continuïteit en discontinuïteit in de naoorlogse geschiedenis van Nederland’, Ons Erfdeel 28, nr. 5 (1985): 659-668, aldaar 660. 2 Een ander monumentaal werk is A study of History (Oxford 1934-1961) van de Britse historicus Arnold Toynbee dat in to- taal 12 delen omvat en meer dan 7000 bladzijden telt. 3 De Jongs oeuvre telt bij benadering 46.500 bladzijden. Zijn journalistiek werk: 24.742 blz. Specificatie: De Groene Am- sterdammer (februari 1937-mei 1940), circa 8000 blz.; Radio Oranje (juli 1940-augustus 1945), inclusief de geallieerde strooibladen De Wervelwind en De Vliegende Hollander en vanaf de bevrijding, Herrijzend Nederland, circa 10.000 blz.; zijn verzetstitel Holland fights the Nazis (1940): 138 blz. en de vierdelige reeks Je maintiendrai (1940-1944) exclusief bijlagen: 1447 blz.; 21 jaar buitenlandrubriek Vrij Nederland (van 1949 tot 1969): 5000 blz. -

The Path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR for More Than 600 Years, a Unique Network HANSA of Merchants Existed in Northern Europe

The path to the FAIR HANSA FAIR For more than 600 years, a unique network HANSA of merchants existed in Northern Europe. The cooperation of this consortium of merchants for the promotion of their foreign trade gave rise to an association of cities, to which around 200 coastal and inland cities belonged in the course of time. The Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages These cities were located in an area that today encom- passes seven European countries: from the Dutch Zui- derzee in the west to Baltic Estonia in the east, and from Sweden‘s Visby / Gotland in the north to the Cologne- Erfurt-Wroclaw-Krakow perimeter in the south. From this base, the Hanseatic traders developed a strong economic in uence, which during the 16th century extended from Portugal to Russia and from Scandinavia to Italy, an area that now includes 20 European states. Honest merchants – Fair Trade? Merchants, who often shared family ties to each other, were not always fair to producers and craftsmen. There is ample evidence of routine fraud and young traders in far- ung posts who led dissolute lives. It has also been proven that slave labor was used. ̇ ̆ Trading was conducted with goods that were typically regional, and sometimes with luxury goods: for example, wax and furs from Novgorod, cloth, silver, metal goods, salt, herrings and Chronology: grain from Hanseatic cities such as Lübeck, Münster or Dortmund 12th–14th Century - “Kaufmannshanse”. Establishment of Hanseatic trading posts (Hanseatic kontors) with common privi- leges for Low German merchants 14th–17th Century - “Städtehanse”. Cooperation between the Hanseatic cit- ies to defend their trade privileges and Merchants from di erent cities in di erent enforce common interests, especially at countries formed convoys and partnerships. -

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE PUBLIÉE UITGEGEVEN SOUS LE HAUT PATRONAGE ONDER DE HOGE BESCHERMING DE S. M. LE ROI VAN Z. M. DE KONING PAR LA DOOR HET SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE KONINKLIJK BELGISCH DE NUMISMATIQUE DE BELGIQUE GENOOTSCHAP VOOR NUMISMATIEK ET SUBSIDIÉE PAR LE EN l'lET DE STEUN VAN HEl' MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE MINISl'ERIE VAN NATIONALE OPVOEDING ET DE LA CULTURE EN CULTUUR DIRECTEUnS : PAUL NASTER, ÉMILE BROUETTE, JEAN JADüT, TONY HACKENS CXVI- 1970 MÉLANGES MARCEL HOC BRUXELLES BRUSSEL AN EARLY CAROLINGIAN MINT IN THE LOW COUNTRES: BONA = TIEL The purpose of this note is to question the traditional attri bution of the pre-reform coins of Charlemagne inseribed BONA to Bonn, and ta suggest that it is very probable that they were struck in the Law Countries, and should be ascribed ta Tiel. The first and most positive reason for doubting the tradîtional attribution is its orthographieal improbability. The name Bonn in the early middle ages was regularly written with a double n : Bonna, Castra Bonnensis, ciois Bunnensis, and 50 on (1). In par ticular, at a date close ta that of the coins signed BONA, the last continuator of Fredegarius writes of Pepin coming in 753 ad cas tro cuius nomen est Bonna (2). Thus the spellings suggest that the word was pronounced with a short 0 or u. BONA for Bonna on these coins on which the mint-name constitutes the reverse type is perhaps not impossible, but it is decidedly improbable. Early Carolingian Latin orthography remained in the classicaI tra dition, and attempted to spell place-names - which of course are in Latin on the coins - with creditable Latinity. -

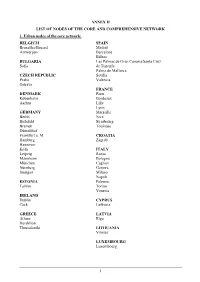

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr.